When one reads that Charles Tomlinson Griffes died at thirty-five (on April 8, 1920), one naturally thinks of Mozart and Schubert. But the association serves only to underline how differently a shortened life affected the career of the turn-of-the-century American composer. Mozart and Schubert both seem to have crowded in a full lifetime’s work, if not more, in their few years; they seem to have done what they set out to do, even if each left one major work unfinished. Griffes is the fitting subject for the classic obituary, “struck down in the midst of his career at the height of his powers.” He died from a protracted lung illness just as he was becoming known in East Coast music circles and was drawing courage from his success to venture in new directions. The texture of his music was changing, becoming more advanced and complex, and he appeared to be starting a new career. He became the composer of a major piano sonata after having been a miniaturist, a composer for orchestra and theater after having concentrated on piano pieces and songs. To perfect oneself in these new genres in so few years is more than can be expected of anyone, so it is not unusual to find Griffes’s critics maintaining that he had left “his achievement incomplete,” in the words of a fellow composer, Frederick Jacobi.

As Griffes’s own times recede the innovations he might have bestowed upon his contemporaries become less consequential, and we can dwell upon what he actually accomplished rather than upon what he might have done. Had his composing career somehow come to an end four years earlier, in 1916, it would have seemed an orderly progression. Born in Elmira, New York, in 1884, he had prepared himself for a career as a pianist, and, not unexpectedly, he wrote a number of fine keyboard works. But some sixty songs, almost all written during the period in question, might well qualify him as primarily a song composer. This may come as a surprise to those who know him only as the composer of The Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan (a symphonic poem), “The White Peacock” for piano, and perhaps also Poem for Flute and Orchestra.

The songs clearly derive from the tradition of the German lied. During his four student years, in Berlin, where at age nineteen he went to study with Humperdinck and others, he used German texts, and continued to do so for some time after his return in 1907, when he began a life of teaching music at a boys’ school in Tarrytown, New York. Even so, the influence of the French Impressionism of Debussy and Ravel began to insinuate itself into his style, and when he turned to English texts it was the French influence that prevailed—as it did in all his music. Indeed there is remarkable consensus in the writing about him that he qualifies as the American Impressionist. The exchange of German style for French neatly parallels the American trend away from the grandiose Central European statement favored by such nineteenth-century academic composers as Edward MacDowell, Frederick Converse, and George Chadwick, and toward the French manner in works like the tone poems of Edward Burlingame Hill and Charles Martin Loeffler. But there was no more apposite vehicle for reaction against Romantic grandiloquence than the Innigkeit of the Lied that Griffes filtered through French art song and imported into American music.

Often Griffes’s piano pieces suggest song accompaniments. Like their French models, these piano pieces are pervaded by a single mood that invites the description “poetic.” They even have extracts of poetry associated with them—words not sung but placed at the head of the score. Sometimes Griffes had the poetry in mind when composing. At other times, as in the delightful Three Tone-Pictures, words expressing the sentiment were added later—the publisher contended they made the music more marketable. Whatever the case, the piano pieces are apt to spring from the same sources that inspire the songs. Although about a third of the songs are in German, there are enough in English to add significantly to our limited supply of American art songs. All of Griffes’s songs, regardless of language, are receiving more and more attention lately, no doubt because of their increasing availability on recordings.1

But the reputation Griffes has for his three celebrated works is such that it takes considerable readjustment before most of us can think of him primarily as a song composer. I found it therefore odd to make my way through Edward Maisel’s detailed, thoroughgoing, mainly chronological account of the composer’s life—a new edition of a book published in 1943—only to be jolted in the last paragraph by the following assertion: “Probably never again in America will there arise his equal as a composer of art songs.”

Advertisement

The sentence stands unaltered from the 1943 book, which remains “substantially the same” in the new edition except for the correction of “minor errors.” Maisel’s extravagant claim sent me back searching through the book to see if I had missed something. His cogent introduction to the new edition quotes Gilbert Chase as saying, “His songs are the best we have,” but this source didn’t impress me and it wasn’t Maisel talking. There was one more possibility: forty-seven pages of notes (unfortunately not indexed) “update” the new edition with much useful material. Among them all I found was a footnote to Maisel’s provocative sentence deploring the lack of appreciation of the art song in America.

Surely in 1943 Maisel must have known of Charles Ives’s 114 songs, and if Maisel was not aware of those of Theodore Chanler2 then he should have been when he added the notes. Yet he takes no account of the work of either Ives or Chanler. I am inclined to wonder, rather maliciously I admit, whether Maisel, lavish though his praise is, felt he was doing less damage to Griffes’s prestige by putting it at the very end of his book. It is rare, as in the case of Hugo Wolf, that a genius for song writing gains entrance for its composer to the highest rank. A poet can be accorded mastery, even genius, for short poems alone. A composer of short forms—whether piano pieces or songs—should be thought of as we do a lyric poet; it is not condescending to exalt Griffes for just those works—that is, for his career up to 1916—in which he fulfilled himself. A neat ground plan of his lifework thus emerges, and we may proceed from there to the problems of his last years, which blur the total picture.

One thing that blurs it is the number of unpublished works3—several early works, but also a few late ones, including the dance scores that especially create a problem in assessing Griffes. The decade between 1903 and 1913 produced four unpublished piano sonatas that are unlikely to discredit the theory of Griffes as a miniaturist up to 1916, since I infer from Donna K. Anderson’s indispensable annotated catalog4 that they range from student to “academic” work, as if Griffes were “honing his craft” for dealing with larger forms. It is the published Sonata for piano of 1918 around which his supporters rally to claim status for Griffes as more than a miniaturist. The sacrosanct sonata form, the abandonment of tone painting for abstractness, and the fifteen-minute duration (his works usually last five minutes or less) combine to present Griffes in a new light, as a composer of substance and dignity.

Maisel devotes a chapter to analyzing the Sonata, though the rest of his book is biographical, dealing with Griffes’s origins, education, amusements, homosexuality, encounters with publishers and musicians, moral beliefs (shaped by the Danish writer, Jens Peter Jacobsen), and, in lurid detail, his final illness. That an entire chapter is devoted to the Sonata prepares us for its high praise better than we are prepared in the case of the songs. The observation in the introduction that the work is a “landmark in American music” also helps. But the praise when it does come is equally jolting:

Rudolph Ganz on first hearing the Sonata adjudged it the finest abstract work in American piano literature. This was also the opinion of several other contemporaries, and posterity has seen no reason to alter the verdict. The Sonata remains today a solid and formidable landmark in American music….

The ambiguity of the passage opens it up to the interpretation that as of 1943 when these words were written the Griffes Sonata was still adjudged the “finest.” We can give Maisel the benefit of the doubt and assume he would not allow himself to overlook such major works as those of Sessions and Copland which were written in the meantime. But even to maintain that the Griffes Sonata was the finest of its genre written up to its own time is to ignore the Ives “Concord” sonata and MacDowell’s “Eroica” sonata, both of them abstract works notwithstanding their subtitles. Whether Maisel considers them superior or not, he would have helped to put Griffes’s achievement in perspective if he had discussed them.

There would be less reason to be exercised if I did not think Griffes’s Roman Sketches for piano, composed between 1916 and 1918, may be better than his Sonata—or at least as good. In the best of the shorter piano works Griffes purified his idiom of the rhetoric that tries to creep back into the Sonata (listen to the portentous octaves directly after the opening flourishes). Also, some of the bravura passages of the Sonata come precariously close to the stock-in-trade scales and arpeggios that he had gradually discarded. The Sonata is not without its inspired passages, not without a certain grandeur, but the first of the Roman Sketches, “The White Peacock,” is more consistent and retains its charm despite its familiarity. The other Sketches have still higher qualities. In “Clouds” there is the delicate way in which consonance is peppered with chromatic dissonance, achieving an effect not unlike that of the presentation of the rose in Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier. A consonant context such as this one underscores dissonance instead of making it more palatable, and though Maisel does not chronicle caused by Griffes’s harmonic freedom, the reviews of the day brand him as “ultramodern,” even “futurist”—which we find hard to believe, immune as we now are to the shock of dissonance, and knowing that such of his contemporaries as Schoenberg and Edgard Varese were so much further along in carrying on a revolution that involved a good deal more than dissonance.

Advertisement

Another of the Sketches, “The Fountain of Acqua Paola,” brings to mind Ravel’s Jeux d’Eaux, and the way in which the American departs from an idea similar to that of the Frenchman helps to define Griffes’s own procedures in comparison to those of French Impressionism. Ravel’s glittering figure, limpid and at first unchanging, is noticeably reshaped by Griffes, and the total effect is altered by the underpinning of an arched, conventional tune that gives directedness to what the French Impressionists prefer to maintain as a level, static environment. Griffes complained of Debussy’s “thin texture of mood painting with little thematic material of any kind.” His own songs favor a long, hill-and-dale line over Debussy’s declamation—his dwelling on repeated notes within a narrow pitch range, and with breathing spaces, produces an effect that resembles speech. The pulverization of form endemic to twentieth-century music, forecast by Debussy’s short breathed lines, is something Griffes never embraced. Anderson observes that three very brief pieces for piano, written by Griffes just before his fatal illness, are “in texture, at least,” much like Schoenberg’s Sechs Kleine Stücke, Op. 19, and Scriabin’s Preludes, Op. 74. These pieces, which Anderson has edited under the title “Preludes,” are from a projected set of five, described in a letter by the composer as “experimental.” They have none of Schoenberg’s fragmentation.

Yet it is significant that Griffes should have made any move at all in this avantgarde direction. He had found Schoenberg’s Opus 19 to consist of “strange nothings,” and, as if keyboard virtuosity had special virtue, had added, “very easy to play.” That was in 1915. One can only conclude that the people and music he encountered soon after broadened his interests. Among them were Varèse, Darius Milhaud, Marion Bauer, Leo Ornstein, and above all, the remarkable critic of the arts, Paul Rosenfeld. Rosenfeld had unique intuitions capable of divining new talent; for many of us he made being involved in the world of modern music an exciting experience. No one has appeared in the critical establishment to replace him. It was enough for him merely to sense potential, and that is what he sensed in Griffes when he wrote “Mr. Griffes En Route,” in The Seven Arts. This was a review of The Kairn of Koridwen, the first of the three late dance dramas.5

Maisel refers to the review as “the prime example of first-rate attention paid to Griffes by a contemporary critic.” Though the entire review was given as an appendix to the 1943 edition of his book, Maisel has unhappily dropped it from the new edition. (Did he think that the late critic’s name no longer counts? Or that his rich prose may seem quaint today?) Maisel gives only a meager excerpt from the review in the notes; in his main text there is plenty of space for journalists who have thoroughly discredited themselves with their pronouncements upon some of the leading composers of the century. Admittedly, Griffes’s successes can be documented by his reception in the press, but for this purpose a sentence or two would have sufficed.

The most telling observation in “Mr. Griffes En Route” is this:

His talent for the first time has made a satisfactory manifestation. An idiom a little undecided, a little derivative, a personal expression a little hesitant, has become formed and individual and respectable.

Rosenfeld goes on to say that the score is “uneven” and “one would like to see him try his hand at a more grateful subject.” But he implied that Griffes bears watching, and when Rosenfeld thought a talent should be watched he meant it literally and from up close. A warm friendship developed between the two men but no one who knew Rosenfeld would claim that this would have skewed his judgments. Rosenfeld, in my view, would not have looked kindly on the high-flown pianism of the Sonata (how can Maisel say, “It has no pianistic ambitions”?). I like to think he would have discovered more quality in the strange, haunting late preludes.

In his last years Griffes was only starting to venture into orchestral and chamber music. He had written for orchestra as a student, but in 1916 a fellow musician to whom he showed a draft of The Pleasure-Dome responded by lending him a copy of Forsyth’s orchestration book. Like many a young composer since, when obliged to confront the mass symphony audience with no apprenticeship at all, Griffes managed to do a professional job based on reliable sources (Stravinsky, among others). The Pleasure-Dome succeeds on its own fairly modest terms, but having evolved out of a piano work that had occupied Griffes since 1912, it lacks the sophistication of his later music. It is not a fulfillment of his powers as an orchestral composer. The Pleasure-Dome, as far as I can determine, is the only bona fide work for large orchestra that Griffes left us. “Poem” is for strings with a few additional instruments, and the other “orchestral” works are arrangements that are for reduced orchestra or chamber ensemble. Some of the arrangements—among them Three Poems of Fiona MacLeod, one of Griffes’s most felicitous achievements—seem to have been made to profit from a sudden demand for his work after the composer had had some success with Pleasure-Dome.

Maisel promises us that we will alter our view of Griffes when we know the three last dance scores, and he quotes Rosenfeld who, referring to The Kairn of Koridwen in 1940, wrote, “the eminently romantic music moving ‘in thrall to keltic magic’ exhibits at the very least as much talent and certainly more taste and sensibility than does the famous Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan.”6 But while the promise that Maisel evokes may be well founded, it would be wise not to set our hopes too high. Rosenfeld thought that The Kairn was flawed in its last half. The pantomime Sho-Jo, second of the dramas, can only be heard in a version for conventional orchestra, since the original chamber score is lost. Salut au Monde (based on Whitman), the last dance score, was left unfinished. I have not seen it. Supporters of Griffes speak of it with special reverence, but the fact that the one salvageable act (out of three) had to be reconstructed from the composer’s sketches—by “a heavier hand,” according to Rosenfeld—does not raise hopes for it. Also, for my part, the Orientalism is not the side of Griffes I prefer. Finally, from what can be inferred, the music of the dance dramas leans heavily on the action, which is likely to seem dated in its art-deco exoticism and its affinities with the manner of the legendary Isadora.

In short, we should consider Griffes as a composer “en route” rather than arrived. And we ought to hear the dance scores if we are to assess what I see as Griffes’s second career. Maisel’s book shows the slow development toward that career as Griffes gradually accumulated people who helped and influenced him until his prospects, like a spark that slowly catches on, were to burst into flame. Maisel tells with much sympathy how Griffes, weighed down for over a decade up to his final illness by his teaching in Tarrytown, regularly made the trek to New York City to petition publishers and meet influential musicians. He thus broke out of his isolation and was encouraged to wean himself away from songs and piano pieces. Fellow musicians, for example, persuaded him that The Pleasure-Dome was unsuited to the keyboard, and when hope for an orchestral performance seemed realistic, he completed the orchestration. In response to such stimulation he suddenly began writing much more ambitiously—which suggests that he might have earlier confined himself to songs and piano pieces out of expedience rather than choice.

In view of this background, experiences that in other artists may have little to do with their art become pertinent. We require personal information about Griffes to understand his evolution, and Maisel energetically satisfies that requirement. Though he might have been more sparing with superlatives, admiration for his subject brought with it much dedication in dredging up material. It would have been useful, however, if he had paused in his almost breathless chronology to sort out the categories of Griffes’s music, and trace the development within each. Instead he offers to the lay reader what is essentially a music appreciation guide to the Sonata, and to the musical reader a variety of interval analysis that has been much improved since 1943.7 Other digressions from chronology deal with Griffes’s quasi-religious brand of atheism and his soul-searching attitude toward his homosexuality. The quoted passages from his letters and diary are so lively that they make one want to read more. By laying the groundwork for future study of Griffes’s music Maisel’s book should certainly attract attention to a composer who is more important and fascinating than he has been given credit for being. It should force readers to revaluate him—but in their own way, we may hope, not Maisel’s.

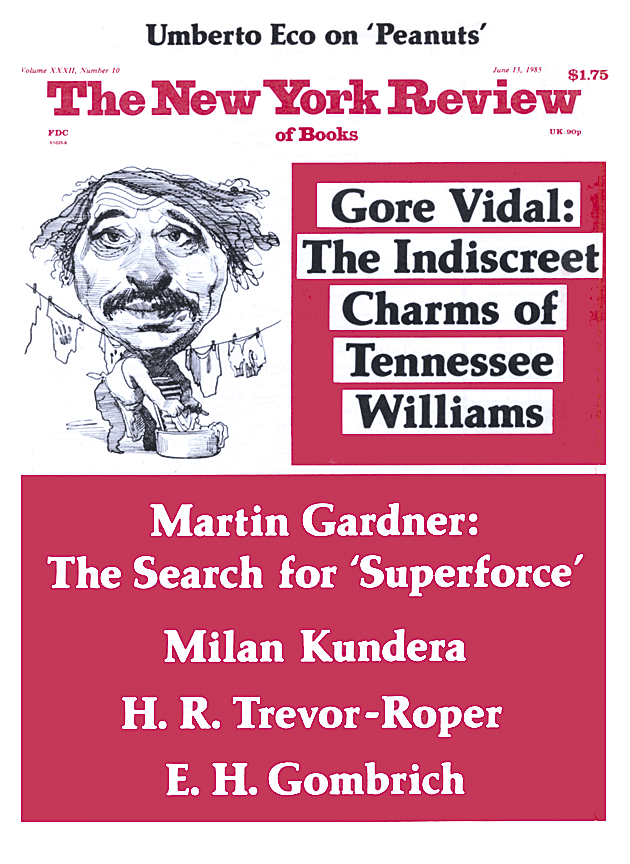

This Issue

June 13, 1985

-

1

Notably The Songs of Charles T. Griffes, Musical Heritage Society, MHS 824678M. Also, there are some songs on a Griffes album of New World Records, NW 273. ↩

-

2

Chanler’s oeuvre was small but choice. ↩

-

3

Griffes’s original publisher, G. Schirmer, Inc. until 1951 held on to several compositions to which it owned the rights without issuing them. Since 1967 Peters Edition has been performing the service of gradually making the unpublished works available. ↩

-

4

Anderson’s catalog (The Works of Charles T. Griffes: A Descriptive Catalogue) is a musicological work based on her Ph.D. dissertation and naturally addressed to the specialist. It was an enormously helpful reference in preparing this article. ↩

-

5

The Seven Arts 1 (April 1917), pp. 673–675. ↩

-

6

“Griffes on Grand Street,” Modern Music 18/1 (November–December 1940), pp. 27–30. ↩

-

7

Maisel is more attentive to technological progress than to progress in music theory, since he did take pains to update his old instructions for following his analysis with the aid of a ruler on 78 rpm records. In the analysis Maisel is on the right track in seeking congruence of intervals, but he need not have been stumped by what he calls a “rebellious” F which, he says, should be F-sharp. The F-sharp in the left hand counts, and using both notes we get the symmetry of two four-note scale segments (tetrachords) related by retrograde-inversion: from C-sharp, two half-steps and a whole; from F-sharp, a whole and two half-steps. ↩