Beirut, 1963: a Muslim secondary-school classroom, full of eager young Arab nationalists in their final year. The visitor, a Shi’ite Muslim cleric, recent immigrant to Lebanon from Iran, doesn’t arouse much interest—even if (with hindsight at least) “there was something special about him. He cut a striking figure. His looks—he was a very tall man—his aura, and the neatness of his clerical attire marked him as someone different.”

Why not? Not because most of the pupils are—by family origin if not by intellectual conviction—Sunni Muslims. That distinction may be crucially important to their future careers but it is not one they would choose to emphasize now. On the contrary, what alienates them from this visitor is precisely that his clerical status and garb implicitly stress the importance of such distinctions, and that this is a feature of their country which these youngsters regard as an obstacle to its progress and development.

At least one of the pupils is in fact himself from a Shi’ite background in Lebanon’s rural south, but he if anything shows even less interest in the visitor than his fellows. Why draw attention to one’s membership in a despised minority, when the attraction of the prevailing Arab nationalist ideology is precisely that it enables one to be accepted on equal terms? Above all, why do so by identifying with a figure whose Persian accent hints at something non-Arab in one’s own origins, and a member of that clerical caste which has done so much to keep the Lebanese Shi’ite community separate, ignorant, and subservient?

So two travelers pass on intersecting paths, without noticing each other. A year later, his secondary schooling complete, the young Shi’ite assimilé (as he describes himself) will leave Lebanon for America. He will live through the trauma of being an Arab in the United States during the Six Day War of 1967; will see his one-time idol Gamal Abdel Nasser dethroned; will see, sooner than most of his Arab contemporaries, the hollowness of Arab nationalism; and will find a different, more personal escape from his Lebanese sectarian destiny in American citizenship and a brilliant American academic career, built largely on incisive exposure of the follies of his fellow Arabs.

Meanwhile, back in Lebanon, the tall, handsome mullah will assume the political leadership of the underdog Shi’ite community, will endow it with a new selfrespect, teach it how to claim its due share within Lebanon’s sectarian spoils system: he will teach it how to fight, figuratively at first, later (as the spoils system breaks down into outright war) literally. Then, in 1978, just when the Camp David Accords are about to plunge the Arab world (and therefore Lebanon) into a new conflict of unprecedented bitterness, just when revolution in his native Iran is about to make Shi’ism a force throughout the Middle East and far beyond, he will disappear mysteriously, providing his followers with a brand-new version of the Messianic myth which has always been one of Shi’ism’s great strengths: the Hidden Imam, the Awaited One, who is not dead but biding his time, whose example continues to inspire, whose presumed sufferings shame and challenge the faithful to new efforts, whose authority is available to lesser leaders speaking in his name. Vanished, he fulfills his own early promise in a way that his mere corporal self never could have. The once despised Shi’ite Muslims, with whom the earnest schoolboy of 1963 did not care to be publicly identified, are now the most powerful community in what is left of Lebanon—feared and resented not only by fellow Lebanese but by Sunni rulers all over the Middle East, by Lebanon’s most powerful neighbor, Israel, and even by the most powerful nation in the world—which is of course also the earnest schoolboy’s adopted country.

The mullah’s name was Musa al Sadr. The former schoolboy, Fouad Ajami, left his earnestness behind long ago, together with his Arab nationalism and Lebanese nationality. His Arab origins, and Arab nationalist past, gave him the authority and the insight to explain the bankruptcy of Arab nationalism in a series of writings during the 1970s, culminating in The Arab Predicament.* In the wake of that bankruptcy, Western fears and obsessions about the Middle East have had to become more specific. Now it is Ajami’s Lebanese Shi’ite origins that come in useful, enabling him to explain—again with great insight and authority—the social and ideological background of those who go so far as to blow themselves up, taking 241 US Marines with them, or to hijack an American aircraft and demand the release of coreligionists deported to, and detained in, Israel. Hence the present book.

But there’s something more to it than that—something that gives Ajami’s new book an intensity that his earlier one did not have. Could it be the development of the author’s prose? In part at least, yes. English is not Ajami’s mother tongue. Yet to compliment him on the mere fluency with which he writes and speaks it would be grossly condescending. His use of the language represents one of those periodic transfusions of new blood which ensure its perennial vigor. Straying a little from the strict responsibilities of a book reviewer, I can testify that he is a remarkable speaker, having several times been fortunate enough to hear him breathe life simultaneously into an otherwise tedious conference on Middle Eastern politics and into bits of our language—the word wrath, for instance—which, had I not heard him pronounce them, I would have supposed irretrievably lost to colloquial usage.

Advertisement

The same quality infuses his writing. Very occasionally one can think one has caught him misusing the language—for example when he writes of “the strictures of Najaf—the religious hierarchy, the scholarly seniority,” or again “the strictures of the narrower and politically worsted Shiism.” Strictures here seems to be used as a rough synonym for “rigidities”—not its normal meaning in modern English. But according to The Shorter OED, stricture meaning “strictness,” now obsolete, is found in Shakespeare. Does Ajami know this? I suspect not, but it doesn’t matter. His pen is guided by his ear, which accurately conveys the overtones the sound of the word strictures will carry.

No wonder the book opens and closes with quotations from Conrad, the greatest of all “foreign” writers of English, whom Ajami clearly aspires to emulate but has the sense not to imitate. But it would be pretentious to suggest that its main interest lies in virtuosity of style, which soon becomes tiresome if it fails to carry the reader’s attention beyond itself to the thought it is being used to express. What gives this work its special zest and urgency is the relationship between author and subject—the hint of regret, implied but never stated, at that nonmeeting of minds in the Beirut schoolroom.

When Ajami wrote about Arab nationalism he was writing of something he had lived through and grown out of. In recounting the epic of the Lebanese Shi’ites he is writing of something he might very easily have had a part in, perhaps even a leading one, but did not. It is almost as if one were to discover a life of Christ written by the young man who, when invited to sell all he had and give to the poor, went sorrowing away. Not that Ajami has belatedly become a believer. He entertains no fantasy either of Musa al Sadr, who disappeared mysteriously in Libya, being still alive or of the Shi’ite epic being a success story. “Musa al Sadr,” he concludes,

led his Lebanese followers at a time when they were beginning to make a claim on their country. He vanished and left them with a text and a memory and some institutions at a time when the country as a whole had become a ruined place. Young men behind sandbags, with their Imam’s posters, defend the ruins that are theirs and their sect’s.

The only achievement of the Shi’ites is that no one else in Lebanon can now claim to be any better off than they. One who has escaped to another world—a world of MacArthur Prize fellowships and chairs of Islamic studies—knows better than to envy them. Nor is he so vain as to feel guilty at having “abandoned” or “betrayed” them by taking the path he did. Great as are his talents, the task of civilizing Lebanon would have been beyond him.

Yet they are still his people. That fact leaps from every page of the book, and would do so even if the author told us nothing about himself (as indeed, after that first anecdote of the classroom, he does not) and we had no other knowledge of him. Even the Shi’ite religious tradition is described with a certain pride: pride in its tenacity through the long centuries of persecution, pride in its readiness (unlike Sunni Islam) to draw a sharp distinction between the reward of virtue and mere worldly success, pride in the solace it brought to the defeated and deprived, pride in the learning transmitted across great distances of space and time. This is a pride which the seventeen-year-old assimilé of 1963 presumably either did not feel or had firmly repressed. His ability to express it now suggests that, even as an American academic, he has not wholly missed out on the benefits brought to his community in Lebanon by Musa al Sadr.

Advertisement

More spontaneous, perhaps, is the venom with which Ajami describes the social order of the Lebanese Shi’ites as Musa al Sadr found it—and as he, Ajami, presumably remembers it from his own childhood. Unforgettable, in any case, is his pen portrait of Ahmad Bey al Assad, “quintessential zaim [big man] of the 1940s and 1950s” who “prided himself that, if he wished, he could get his cane elected to parliament,” who told a delegation of villagers they had no need of a school “for he was educating his son Kamel Bey for all of them,” and who took an escort of five hundred armed men with him to the Beirut airport to greet the son when he returned from his studies in Paris. Even more unforgettable is the portrait of Kamel Bey himself, who succeeded his father in the early 1960s and “would make the men of the south miss the old man and his fez and his old-fashioned tyranny”:

His power came with insecurity. No Shia, it was reported, was allowed into the younger bey’s presence with a necktie. Accomplished men with education and money ushered in to see him had to remove their neckties. Only the bey himself could wear modern attire. The rest had to avoid his wrath; they had to be peasants, to identify with his power, with his sexual exploits, with the way he humbled this or that man by having his way with the man’s wife. They had to live off his triumphs, a man of their own faith, walking for them into alien worlds.

Kamel Bey was good at mimicking the Shia manner of speech and those Shia words that mothers said to their sons, the words of peasants—the words of piety and defeat. When a Shia man from the south stepped out of line, he was in for a dressing down. Kamel Bey loved to humiliate men in the presence of others. The more accomplished, the more “uppity” the man, the more Kamel Bey enjoyed humiliating him in public, mocking his achievements and his education.

It is a picture worth bearing in mind whenever one hears people being lyrically nostalgic about the douceur de vivre of prewar Lebanon.

Repeatedly, Ajami stresses the appeal of Musa al Sadr to the Shi’ite évolués—people who, like Ajami himself, had somehow escaped the quasi serfdom that was the lot of their coreligionists either by getting an education or by going abroad and making money (usually in West Africa), but who, unlike him, had returned to Lebanon looking for something better than the marginal role accorded to them by the National Pact—the famous sharing of power sealed in 1943 between Sunni Muslims and Maronite Christians, in which only the crumbs fell to a handful of hereditary Shi’ite magnates like the al Assads. Clearly it was among this group that he found his best sources, both for his reconstruction of Musa al Sadr’s actual career and, more important, for his analysis of the “Imam’s” constituency and the nature of his appeal to it. These men themselves—Shi’ites with money and/or qualifications but lacking status in the existing political order—were evidently an important part of that constituency. Like Ajami they were revolted by the traditional Shi’ite clerics whose meager learning was used to nurture the superstition of the peasants and perpetuate their servile allegiance to the al Assads and their like. Unlike him, they stayed to listen to, and be inspired by, the activist, modernist version of Shi’ism which Musa al Sadr gradually developed.

It had something in common with that of his Iranian contemporary, the sociologist Ali Shariati. Ajami quotes a eulogy delivered by Musa al Sadr on Shariati’s death in 1977, a year before his own disappearance, as “a fair summation of where he himself stood, of what he had attempted to do.” Of course there are differences: Shariati was above all a thinker, steeped in the works of French-speaking writers like Louis Massignon, Frantz Fanon, and Jean-Paul Sartre. He had more enforced leisure for reflection, less opportunity (and no doubt less ability) to found and lead a mass movement. His pronouncements seem more mystical, less down-to-earth. But both men had to choose their words with care, taking into account the sensitivities of more than one audience. Both criticized the traditional clerics for their failure to stand up to oppressors. Both were seeking to articulate an Islam that could compete with communism and other ideologies of Western origin on their own terms, to restore confidence in their own culture and religion to young people disoriented by half-understood Western ideas, to popularize the notion that in speaking up for Islam (and specifically Shi’ite Islam) one was not demanding a return to obscurantism but working toward liberation and enlightenment. Both were to be claimed as martyrs and progenitors by the Islamic Republic of Iran and its protégés in Lebanon and elsewhere. Neither stayed around to incur the odium of choosing between “fundamentalist” and “modernist” interpreters of their legacy.

Ajami is a disciple of neither. He sees now, and probably would have predicted even then, that all that uplift, all that ingenious synthesis of East and West, of traditional and modern, all Musa al Sadr’s skill in picking his way through the mine field of Lebanese politics, would lead nowhere except to different patterns of tyranny and carnage: “When the excluded stormed the citadels, many of them smashed through with little if any mercy for others, or any grace.” Indeed, Shi’ite rule in West Beirut since 1984 has been even more ruthless, more anarchic, more incompetent than the regime of the PLO which the city endured between 1976 and 1982, so that—incredible as it may seem—many Beirutis are hoping, if no doubt misguidedly, for Yasir Arafat’s return.

And yet, among those who responded to the “Imam’s” call Ajami seems to recognize a bit of himself, and when he attributes to the Shi’ites of Beirut a kind of self-reproach about their attitude to the “Imam” while he was still among them in flesh and blood, one catches a hint of apology also for his own detachment:

Deep down, newly dedicated men must have remembered what the recent past was really like; they knew that the revered man did battle for their loyalty and the loyalty of their kinsmen against the normal range of human temptations: the desire for safety, the desire to be left alone, the tendency to see a scoundrel in every hero, the search for individual gratification. But imagination had worked wonders, had attributed to the missing cleric all sorts of powers he had not had.

Some of Ajami’s former compatriots may say it is safer and more comfortable to be a MacArthur fellow and write widely praised analyses of Middle Eastern politics in Foreign Affairs than to involve oneself personally in the hideous politics of Lebanon. But Ajami’s scholarship is not of the merely comfortable sort. He brings to the description of the Shi’ite movement in Lebanon an empathy that bespeaks an ability to visualize himself as part of it, if only history had taken a slightly different turn in that Beirut classroom, twenty-three years ago.

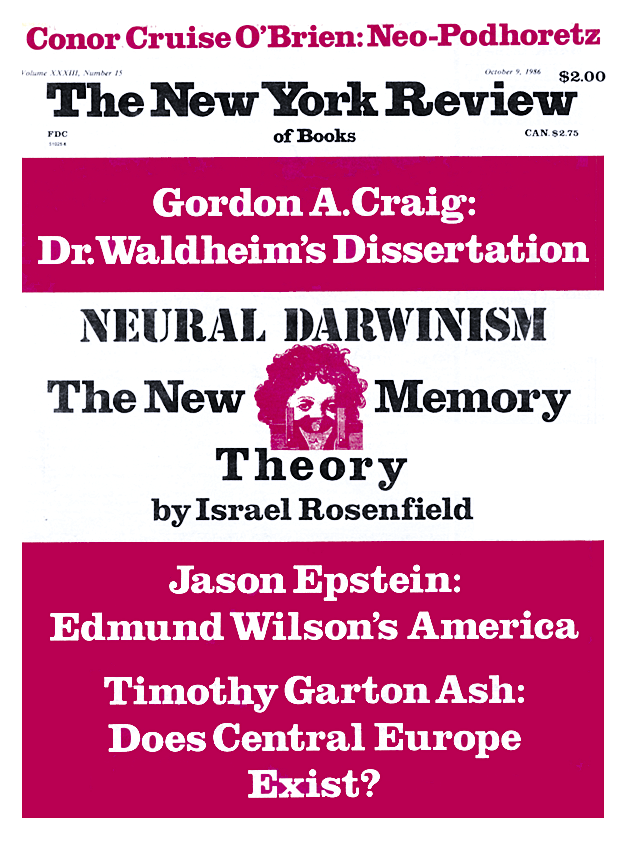

This Issue

October 9, 1986

-

*

Cambridge University Press, 1982. ↩