Memorial Day, 1986. Laying a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery, President Ronald Reagan paid special attention, in his remarks, to “the boys of Vietnam…who fought a terrible and vicious war without enough support from home…. They chose to be faithful. They chose to reject the fashionable skepticism of their time. They chose to believe and answer the call of duty.”

Ronald Reagan was adopting for his own ends one of the enduring conservative myths of the Vietnam War, that never were so many betrayed by so few. It has become a commonplace in the conservative canon to compare the combat hardships endured by the troops in the line with the cowardice of the military deserters in the field and the draft resisters at home. The truth is more ambiguous. In what Lawrence Baskir and William Strauss call the “Vietnam era”—that is, between August 7, 1964, when the Senate passed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, and March 29, 1973, when the last US combat forces left Vietnam—26,800,000 American men came of draft age. Of that number, there were 570,000 apparent draft evaders. Another 15,410,000—or 57.5 percent—were “deferred, exempted, or disqualified,” one of whom, on medical grounds, was Ronald Reagan’s eldest son.

Class was always the domestic issue during the Vietnam War, not communism. At the peak of the conflict, draftees were getting killed at twice the rate of enlistees, with the result that avoiding the draft became the preoccupation of an entire male generation, or at least that part of it which had the means and the wit to manipulate the Selective Service system to its advantage. Evading military service has a long history in American life. During the Civil War, Union conscripts could buy a substitute for $300; in the South, plantation owners could keep their sons home under the so-called 20-Nigger Law, which exempted one overseer for every twenty slaves. So many registrants had their teeth pulled to avoid induction during World War I that the War Department had to warn dentists publicly that they were liable for prosecution for abetting draft dodging. Only World War II, which mobilized 10 million draftees, could by any stretch of the imagination be called a people’s war.

The men “who fought and died in Vietnam,” write Baskir and Strauss, “were primarily society’s ‘losers,’ the same men who got left behind in schools, jobs, and other forms of social competition.” In other words, a rainbow coalition of black, brown, and redneck who, according to the Notre Dame survey which was the inspiration for Chance and Circumstance, were “about twice as likely as their better-off peers to serve in the military, go to Vietnam, and see combat.”

The documentation presented by Baskir and Strauss, and by Myra MacPherson in Long Time Passing is relentless. A survey conducted by Congressman Alvin O’Konski of one hundred draftees in his northern Wisconsin district showed that not one came from a family with an annual income of over $5,000. Another survey, in 1965–1966, indicated that college graduates made up only 2 percent of all inductees. Of the 1,200 men in the Harvard class of 1970, only fifty-six served in the military, just two in Vietnam. People disposed to the war showed no more inclination to serve than those with antiwar attitudes. “A 1970 report showed that 234 sons of senators and congressmen came of age since the United States became involved in Vietnam,” MacPherson writes.

More than half—118—received deferments. Only 28 of that 234 were in Vietnam. Of that group, only 19 “saw combat,” Only one, Maryland Congressman Clarence Long’s son, was wounded…. No one on the House Armed Services Committee had a son or grandson who did duty in Vietnam. Student deferments were shared by sons and grandsons of hawks and doves alike. Senators Burdick, Cranston, Dodd, Goldwater, Everett Jordan and McGhee had sons who flunked the physical.

II-S was the magic classification that guaranteed deferment for college students. In the Vietnam era, male college enrollment averaged 6 to 7 percent higher than in the years immediately preceding. Graduate schools were also II-S draft sanctuaries until 1968, when the Selective Service lifted this exemption. An exception was made for divinity schools, which immediately transformed theology into a popular graduate academic discipline. The Harvard Divinity School attracted David Stockman. “Once I went to divinity school I never worried about the draft that much,” Stockman told MacPherson. In 1981, when he became Ronald Reagan’s director of the budget, Stockman moved to cut, as “a dispensable expenditure,” funding for Vietnam Vet Centers, in the process calling Vietnam veterans “a noisy interest group.”

When the potential draftees finally reported for their preinduction physicals, approximately half were rejected, which was two to three times the rejection rate for the NATO allies. There was, among those with sufficient motivation, a virtual pandemic of asthma, bad backs, trick knees, flat feet, and skin rashes. Hawks who would later describe the war as a noble cause were no more immune to this scourge than doves; Patrick Buchanan had a bad knee, Elliott Abrams a bad back, Congressman Vin Weber asthma. Congressman Newt Gingrich told Jane Mayer of The Wall Street Journal that Vietnam was “the right battlefield at the right time,” but when asked why he had not served, Gingrich replied, “What difference would I have made? There was a bigger battle in Congress than in Vietnam.” In fact, Gingrich was not elected to Congress until 1979, having spent his draft-age years during the war earning a baccalaureate, master’s, and Ph.D. at Emory and Tulane, and teaching at West Georgia College.

Advertisement

“The preinduction examination process,” Baskir and Strauss write, “rewarded careful planning, guile, and disruptive behavior.” Draft counselors seized on a loophole in the law that gave every registrant the right to choose the site of his preinduction physical. “For most of the war,” Baskir and Strauss say,

Butte, Montana, was considered an easy mark for anyone with a letter from a doctor, and Little Rock, Arkansas, for anyone with a letter from a psychiatrist. Beckley, West Virginia, was well-known for giving exemptions to “anyone who freaked out.”… By far the most popular place to go for a preinduction physical was Seattle, Washington. In the latter years of the war, Seattle examiners separated people into two groups: those who had letters from doctors and psychiatrists, and those who did not. Everyone with a letter received an exemption, regardless of what the letter said.

For those who did not wish to chance the preinduction physical, however many medical affidavits loaded the dice in their favor, the reserves and the National Guard beckoned. In 1969 and 1970, the reserves and the Guard welcomed 28,000 more college-educated recruits than were enlisted or drafted into all the other services combined. In 1968, the Guard had a waiting list of 100,000 men; one Pentagon study showed that 71 percent of all reserve and 90 percent of all Guard enlistments wanted to avoid the draft. This was a force in which Jim Crow appeared to be the recruiting sergeant; only 1 percent of the total strength of the Guard nationwide was black. (It should further be noted that according to a 1966 report a mentally qualified white male was 50 percent more likely to fail his preinduction physical than his black counterpart.)

Professional athletes were particularly attracted to the reserves and Guard. While the magnates of professional sports have always had an almost mystical devotion to the flag, this devotion, during the Vietnam War, did not extend to volunteering their athletes to get shot in defense of it. Ten members of the Dallas Cowboys were assigned to one National Guard division, the backfield of the Philadelphia Eagles to the same reserve unit. The chances that Lyndon Johnson would mobilize all or most of the 1,040,000 in the Guard or the reserves were always minimal. This was a constituency of the white, the well-to-do, the well educated, and the better connected, and to activate them would have brought the war into the venues whose support Johnson most feared losing. In all, only 37,000 men from this manpower pool were called up, and of these, just 15,000 went to Vietnam.

The army of the underprivileged that fought was abandoned not only by the antiwar left, but also, Ronald Reagan’s revisionism notwithstanding, by the prowar right, whose rhetorical support for the conflict exceeded its interest in fighting it. The marine platoon on Hill 10, near Da Nang, that William Broyles took command of in November 1969, is a case in point. “I have fifty-eight men,” Broyles wrote at the time. “Only twenty have high school diplomas. About ten of them are over twenty-one.” Broyles goes on: “The average age of the infantryman in World War II was twenty-six; in Vietnam it was nineteen…. In another platoon there was a lance corporal who was twenty-four. He was called Pops.” The service records of Broyles’s men on Hill 10 similarly indicate a platoon of the dispossessed and the disadvantaged: “Address of father: unknown. Education: one or two years of high school. Occupation: laborer, pecan sheller, gas station attendant, Job Corps. Kids with no place to go. No place but here.”

William Broyles is one of the three people I know who served in Vietnam. In Brothers in Arms he tries to calibrate his feelings about the war, about the men he fought with, the men he fought against, and the men who did not go. “I was drafted at the age of twenty-four,” he writes, “and I had spent the previous three years doing my best to avoid military service.” A graduate of Rice University in Texas, he won a Marshall Scholarship to Worcester College, Oxford. The BBC was his link to Vietnam, the television images from Hue during the 1968 Tet offensive his crucible. “Those boys were like the friends I had grown up with in a small town in Texas,” he writes. “They were fighting a war while my friends from college and I went on with our lives. I thought my country was wrong in Vietnam, but I began to suspect that I was using that conviction to excuse my selfishness and my fears.”

Advertisement

He took his preinduction physical in Newark, one of four whites and 146 blacks. “The Army was their escape from the Newark ghetto,” Broyles writes. “They wanted in, not out.” Once in the Marine Corps, he expected, because of his educational advantages, to spend his three-year tour studying Chinese at the language school in Monterey, then translating documents in Washington. Instead he was commissioned as a platoon leader. On his way to Vietnam, he briefly went over the hill, planning a moral gesture against the war. Then he reconsidered and shipped out to Da Nang, finally landing on Hill 10.

The teen-agers in his platoon made it clear they would choose which of his commands to obey. “No way, José,” a nineteen-year-old Cajun point man responded when Lieutenant Broyles ordered him into a tunnel where an enemy soldier was thought to be hiding. A nineteen-year-old squad leader also refused. Broyles went in himself. “Inside the tunnel poisonous snakes might be hung from the ceiling,” Broyles says about this insidious and terrifying underground combat. “A pit might lie beneath the floor, lined with sharpened stakes—perhaps with poison on the tips…. In Vietnam the monster really was under the bed, the tunnel really did suddenly open in your bedroom wall.”

And yet. “It is well that war is so terrible, or we should get too fond of it,” Robert E. Lee said to General Longstreet at Fredericksburg. Broyles’s fondness is at times palpable. He talks about “the soft, seductive touch of the trigger” and the “aesthetic elegance [of] a Huey Cobra helicopter or an M-60 machine gun. They are without artifice, form as pure function.” He is disdainful of napalm.

Greatly overrated, unless you liked to watch tires burn. Far superior was white phosphorus…wreathing its target in intense and billowing white smoke, throwing out glowing red comets trailing brilliant white plumes…. It would transform human flesh into Roman candles…. I knew that, but I still marveled, transfixed. I had surrendered to an aesthetic divorced from that crucial quality of empathy that lets us feel the suffering of others.

Often it seemed to Broyles that his men were more united against their fellow Americans in the cushier billets than against the enemy they were supposed to be fighting. In 1968, at the height of the American involvement, only 12 percent of the troops in Vietnam were assigned to line units, as opposed to 39 percent in World War II. On Red Beach, near Da Nang, there was an air force base with its own massage parlor, while on another beach GIs drew combat pay as lifeguards. Soldiers ran movie theaters and ice-cream parlors, and in Saigon there was a Vietnamese officers club where girls crouched under every table, available for fellatio. Shortly after his arrival on Hill 10, Broyles received a frantic radio message that Da Nang was under NVA rocket attack. The response from his men was not exactly what he expected. They emerged from their hooches, cheering and shouting, “Get those REMFs.” REMFs was military slang for “rear echelon motherfuckers.”

This was an army of the night, a fact Broyles never forgot. He remains fervent in his belief that “the My Lai massacre was result of the system of privilege that kept educated young men out of the military. William Calley…was a dropout and a loser. He should never have been an officer, and would not have been had his more talented peers been drafted.” Nor will Broyles accept the common rationale for Calley’s behavior: “Almost every American who fought in Vietnam went through the booby traps, the ambushes, the frustrations of never seeing the enemy—what Calley’s platoon had been through before the massacre. With only a handful of exceptions in a long war, they didn’t respond by slaughtering unarmed old men, women and children.” A marine in Broyles’s platoon murdered a Vietnamese pimp because one of the pimp’s girls had given him the clap. Broyles turned the marine over to military authorities. He was tried, convicted, and sent to prison for twenty years.

For those in power, Broyles writes, Vietnam was not a war, “it was a policy…an item on the agenda.” It was “fought not for a hill or a bridge or a capital, or even for a cause; it was fought to keep score.” The grunt in the field was also keeping score, and the score he hoped to reach was 365, or the number of days in-country before he was rotated home to the States. “It didn’t matter if the war was going badly or if your unit was in trouble,” Broyles writes.

When your time was up, your war was over…. The ordinary infantryman reasonably thought that the war wouldn’t be won in a year, so why try.

…We had our short-timer’s calendars. Every night we marked off another day. That was our goal…. There was no single goal in Vietnam; there were 2.8 million goals, one for every American who served there.

And in the end the nation’s goal became what each soldier’s had been all along: to get out of Vietnam.

In late 1970, Lieutenant Broyles got out. Fourteen years later, by now a man of affairs who had an entry in Who’s Who and who had been the editor of Newsweek and invited to the White House to attend Ronald Reagan’s private screening of E.T., Broyles went back. The impetus to return came at the dedication, in 1982, of the Vietnam Memorial. “I went back to Vietnam to answer the question, ‘What does it mean to go to war?’” he writes. “I set out to see this long defeat from a different perspective—the winner’s.” Over the four weeks he was in Vietnam, Broyles traveled nearly three thousand miles, talking to soldiers who had fought, as he had, in the paddies and mountains of the South, and trying to find out from their generals “why they won and we lost.”

Like most Americans, Broyles finds it remarkable that the victors still occupy a landscape he calls “pre-industrial,” its beat the rhythm of the rice harvest rather than the demands of technology. The realization slowly takes hold that bombing Vietnam back to the stone age would not have pushed it back all that far. Its mechanisms for confronting the twentieth century tend to bewilder the visiting Westerner. Vietnamese fighter pilots learn to fly jets before they learn to drive a car. At one hospital in Hanoi, cardiologists were using the latest advances in Dutch ultrasound equipment to monitor rare cases of left atrial myxoma, “but there was no blood in the lab refrigerator. The patients lay two to a bed in their own clothes,” and “several pieces of equipment stood dusty and inoperable.” The secret to Vietnam, Broyles is told by Do Xuan Oanh, one of the country’s leading experts on America, “is in the songs of the buffalo boys.” Broyles asks what the songs are like. “Like Bob Dylan’s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues,’” Xuan Oanh replies. Xuan Oanh, who translated Huckleberry Finn into Vietnamese, says that his favorite American writers are Mark Twain, Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, and Sidney Sheldon, the last because “he is very good on the excesses of capitalism.”

The visitor interested in opinions about the war must first endure the standard responses of the communist liturgy, “more or less like grace before a meal”: they had fought with the people, we had fought against them; their cause was just; ours was not; imperialism was destined to be banished from the earth. Only when the litany was finished were Broyles’s questions addressed. In retrospect he came to understand, in a way he never had on Hill 10, that for his former foes “the war was their home.” Old soldiers showed him the scars from wounds received at the hands of the Japanese, the French, the Americans. In Phat Diem, he met a Communist party official who did not see her husband for the nine years he was fighting in the South, and heard from him only once, by letter in 1969. The stories multiplied at every stop, and with them the sense that victory or death had been the only dates on the enemy’s short-timers’ calendars.

“Time was on our side,” General Nguyen Xuan Hoang told Broyles. “We did not have to defeat you; we only had to avoid losing.” American technological superiority was made irrelevant in a war in which, as Broyles puts it, “our enemies steeled themselves to use men as we used bombs.” Ho Chi Minh had stated the equation to the French in 1946: “Kill ten of our men and we will kill one of yours; in the end, it is you who will tire.” The French tired, and then the Americans, each with nearly 60,000 dead. “We had hundreds of thousands killed in the war,” the military correspondent for the Communist party newspaper in Hanoi told Broyles. “We would have sacrificed one or two million more if necessary.”

What Americans would have sacrificed remains a matter of ex post facto patriotism and bravado. “We had business being there,” Elliott Abrams told Myra MacPherson. “And if it would have required a few thousand American troops stationed there for years in order to prevent this extraordinarily damaging American defeat, then I think most Americans would have been willing to do it.” Nearly 60 percent of those on the draft rolls were not enthusiastic at the time about being among those few thousand. “The argument has one basic flaw,” Broyles writes. “Whatever the price of winning the war—twenty more years of fighting, another million dead, the destruction of Hanoi—the North Vietnamese were willing to pay it.”

Because of the price paid, Broyles writes, the “theme of martyrdom is everywhere. The pantheon of Vietnam is filled with heroes who were tortured, dismembered and executed for the fatherland…. They have even built ‘atrocity museums,’ not unlike the Holocaust memorials in Jerusalem and Dachau.” Constantly prodded by Broyles about their own atrocities, the Vietnamese are less forthcoming.

The Communists’ massacre of civilians at Hue and at places like Thanh My are now inconvenient, so they have been airbrushed out of history; they no longer exist. The Communists stand in the flood of history and pluck from the water only what serves the State.

It is for the survivors who have managed to escape from Vietnam to provide the details that do not serve the state. Doan Van Toai was arrested at a concert in Ho Chi Minh City on June 22, 1975, less than two months after the last Americans left Vietnam, and spent the next 863 days in Tran Hung Dao and Le Van Duyet prisons. He was never told what the charges were against him, and until deep in his incarceration his family did not know of his whereabouts, or even if he were still alive. He was a nonperson, guilty of unspecified “suspicious acts” (his arrest may have been a case of mistaken identity, which his captors then did not know how to rectify). He was accused during his periodic interrogations of refusing to “commit himself.”

In fact, Toai’s father was a member of the Vietminh during the war against the French, while he himself, as a youthful pharmacy student, was tossed into jail several times by the South Vietnamese police for his antigovernment activities. Toai describes himself as something of a fence straddler, an opponent of American imperialism and a supporter of the National Liberation Front, although never to the point of actually becoming a member. Buying his way out of the draft, he managed a bank, kept up his secret contacts with the NLF, and held his finger to the wind. “‘Wait,’ I told myself. ‘Buy time, the situation will clarify itself.’” He is almost beguilingly self-aware: “Most of all, I wanted the revolution to justify my indecisiveness—to reveal itself as complex and ambivalent, but in essence good and constructive.”

In prison, Toai hustles to survive, fast-talking himself into jobs as a barber and a kitchen worker and a doctor’s helper, positions that gave him access to much of the inmate population. Amnesty International has called attention to the camps where thousands of Vietnamese arrested in the mid-1970s are still held, some of them, like Toai, opponents of the war who would not “commit” themselves to the victors.* But many of Toai’s fellow prisoners are old-line Communists jailed on the unarticulated grounds that they might become apostates, or even worse, nationalists. And yet, like the aging Party hands in Darkness at Noon, most still keep the faith, viewing their sentences as time in purgatory until heaven is achieved on earth. Conditions are vile, with overcrowded cells—there are sixty-two prisoners in Toai’s—and only a subsistence-level rice diet. Prisoners turn on each other, then are punished by their guards. Jailers beat one prisoner to death after a fight over food; when they realize he has died, they force the cell leader to sign a statement that the prisoner “committed suicide by swallowing his tongue.”

Toai’s back talk constantly lands him in trouble. Once he is sent to solitary, “a tall box six feet long by three feet wide by six feet high,” where he is unable to move because his right arm is handcuffed to his left ankle, his left arm to his right ankle. Finally, more than two years after he was first picked up, Toai is released, the reason for his release as much a mystery to him as his arrest. He was allowed to leave Vietnam and is now living in California.

It is eleven years since the last Americans left Saigon. On June 10, 1986, The New York Times reported that more than three hundred university-level courses on various aspects of the Vietnam era were offered during the 1985–1986 academic year, up from almost none in 1980. Rambo rides the curl of revisionism; a few more with his resolve and the war might have been won. Diligent researchers point out that Sylvester Stallone spent his deferment years first as a coach at a private girls’ school in Switzerland, then as an acting student at the University of Miami, and finally, when the war was winding down, as the star of a soft-core porno film called A Party at Kitty and Stud’s. It does not matter; “the will to win” is the phrase of the moment. In a 1984 campaign film called Ronald Reagan’s America, an homage was paid to “John Wayne, An American Hero.” That John Wayne only played American heroes, and was never in the service where he might have become one, was an irony that went unmentioned. His on-screen image seemed to satisfy some atavistic need exacerbated by the defeat in Vietnam.

This need provides the emotional power of the debate in the Congress over contra aid and the Reagan administration’s Central American policy. Those who served in the armed forces and who have reservations about the military option look with a certain distaste on those who, as Broyles put it in an Op-Ed piece in The New York Times, “avoided service in Vietnam and were miraculously transformed into hawks as soon as they were past draft age.” Congressman Andrew Jacobs (Democrat of Indiana), a former marine, calls them “war wimps.” “Chicken hawks” and “white feathered hawks” are other phrases much in favor. “With the vote on contra aid,” Patrick Buchanan wrote in The Washington Post, “the Democratic Party will reveal whether it stands with Ronald Reagan and the resistance—or Daniel Ortega and the Communists.”

Mark Shields, another former marine and a Washington Post columnist, responded to this with the suggestion that a Paul Douglas Brigade be formed, named for the Illinois senator who enlisted in the marines after Pearl Harbor at the age of fifty. “By now it must be clear that the Reagan administration and Congress are fairly brimming with some authentically Tough Customers who, but for draft deferments for graduate school or a trick knee, would have happily donned the Khaki and kicked a little Commie tail in ’Nam,” Shields wrote. “You have to know if the age and medical requirements were waived for the formation of such a brigade, White House communications chief Patrick Buchanan, Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams and Assistant Secretary of Defense Richard Perle would all volunteer for service in Central America.” Even so civilized a voice as Irving Howe recently suggested, on the Op-Ed page of The New York Times, that “some American hearts might beat a little fast at the sight of rightwingers like William F. Buckley, Jr., and Norman Podhoretz donning fatigues to become contra ‘freedom fighters.’ ”

The question of whether or not one served, or was willing to serve, or would be willing to serve, goes deeper than all the name-calling and the Red-baiting and the Commie-bashing and the allegations of draft dodging that tainted the contra debate, and taint every debate in the Congress about the use of force. At the root of the argument is the way in which war is perceived. “A soldier’s best weapon is not his rifle but his ability to see his enemy as an abstraction, and not as another human being,” Broyles writes. “The very word ‘enemy’ conveys a mental and moral power that makes war possible, even necessary.” Many people in Washington deal only in that abstraction. When Elliott Abrams airily claims that “most Americans” would agree to having “a few thousand” GIs stationed “for years” in Vietnam as the price of avoiding defeat, he is not talking about war, he is talking about war games in the war room, geopolitics, and someone else’s children. War is Hill 10, and a nineteen-year-old squad leader who point-blank refuses an order to go down into a tunnel.

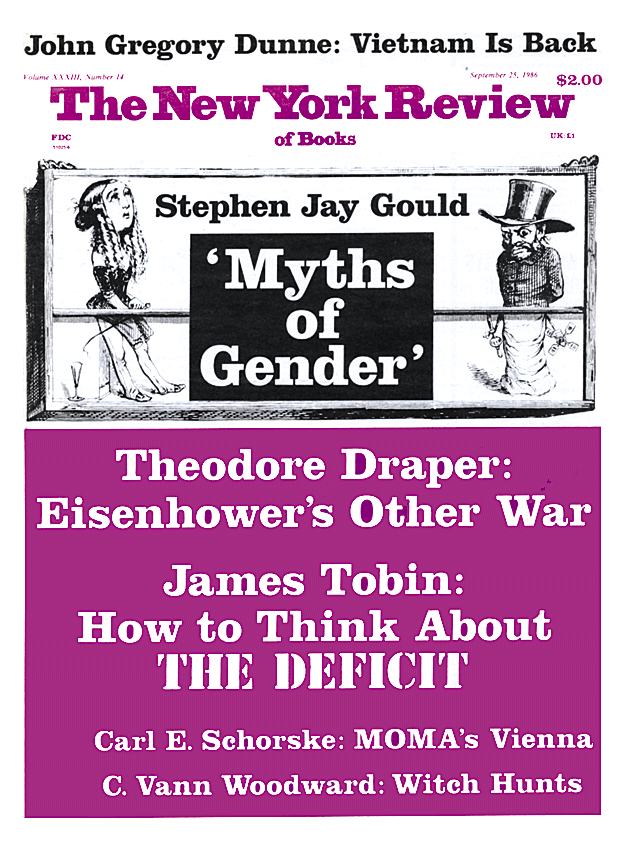

This Issue

September 25, 1986

-

*

See the Amnesty International release, “Socialist Republic of Vietnam: Amnesty International’s Continuing Concerns Regarding Detention Without Charge or Trial for the Purpose of ‘Reeducation,’ ” (April 1985). ↩