It would be impossible to find women who knew more about plantation life under slavery from experience than those who were slaves and those who owned slaves. Yet when the subject is broached today they do not normally come to mind nor is their testimony brought to bear, but rather that of women who were neither slaves nor owners of slaves nor residents in slave states. They were usually women of antislavery or abolitionist views, who thought and wrote about slavery, but who rarely, if ever, ventured into slave quarters or into slaveholders’ company. They lived up North.

In the present instance, however, we have to thank a daughter of the Deep North for digging up and presenting more neglected testimony of plantation mistresses and their servants than has ever before been assembled so fully or organized and analyzed so cogently and provocatively. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese comes from Ithaca, New York, and teaches women’s history in Atlanta at Emory University. From there she has made the most of her opportunities to ransack the archival riches of the Deep South. As a miner of regional treasure she probably has had no serious rival since General Sherman, except that her findings are put to worthier purposes. Her interests and objectives are limited. It would be well to understand first what they are—what she includes and what she excludes.

The title for Fox-Genovese’s book is more successful than titles often are in telling what it is about and what it is not about. It is about the “Old South,” but by no means all of it—whether chronologically, geographically, or demographically. Among demographic elements excluded are the three-fourths of the white families who owned no slaves. Nor does it include the majority of slave owners, for most of them owned fewer than the minimum of twenty traditionally accepted as defining a “plantation.” Excluded also are most of the slaves, since most slaves did not live on plantations, so defined. And of course all males, free or slave, are off limits in a work devoted to women’s history. It would hardly do to call the women Fox-Genovese does include an “elite” since the majority of them were slaves, but they might well be called “exclusive” in a literal sense. The exclusion fortunately permits some account of relations with those excluded by reason of sex or class. Small as it is, it is a highly significant group, especially if one agrees with the author about the dominant role played by plantation slavery in the antebellum South.

First of all, however, this book is intended as a contribution to women’s history and incidentally as a corrective to prevailing assumptions and practices among historians of women. The main target of criticism is their “essentialist interpretation of women’s experience.” By that is meant “a transhistorical view of women that emphasizes the core biological aspects of women’s identity, independent of time and place, class, nation, and race.” Many women’s historians have felt that “to emphasize the class and race determinants of women’s experience…is to compromise the integrity of women’s perception and to mute the pervasiveness of sexism and male dominance.” They have sometimes “written as if class and race did not shape women’s experience and even their identities.” Whatever is written under those misapprehensions “must end in banality.” The work at hand, be assured, is not so written.

To a marked extent new fields of American history, such as women’s history, are now conceived and shaped to serve worthy causes, moral ends. Concerned as it is with righting wrongs, restoring justice, and putting opponents down, such history often takes on an adversarial tone. Professor Fox-Genovese has fortunately avoided in her treatment of the opposite sex an attitude too often found in the work of fellow feminists. Should the adversarial wing of women’s history provoke a reprisal in the form of men’s history—which it already shows signs of doing—I hope that it will follow not only her avoidance of an adversarial position, but also her rejection of an “essentialist” interpretation, and will not try to base the unity and identity of all men on their genitalia and their shared abuse by the gentler sex.

More sound counsel derives from the same source. Fox-Genovese deplores a “tendency to generalize the experience of the women of one region to cover that of all,” to make all conform to “the emerging bourgeoisie” of New England, to celebrate “the fabled middle classes,” “to impose middle-class values on the rest of the nation,” and “to deny the significance of class divisions.” I have never been quite sure where antebellum slaveholders and their human property belonged in any proper Marxist hierarchy of classes, but it is clear that they did not belong to “the emerging bourgeoisie,” and I agree that to make them conform to that model “requires some fancy footwork.”

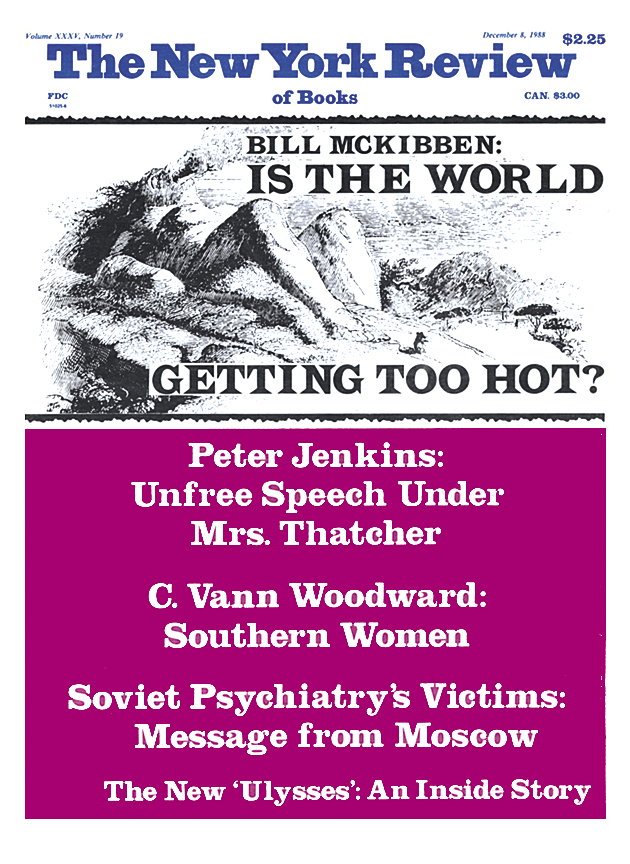

Advertisement

Granted the distinctiveness of southern womenfolk, what made them so different from their Yankee contemporaries? For one thing, according to Fox-Genovese, membership in a “household” (in an anthropological sense), “the primary locus of southern women’s experience,” which was still “the fundamental productive and reproductive unit of slave society,” and had “deep ideological differences” from the northern “home.” A second source of distinctiveness for southern women was the pervasive sort of male domination to which they were all subjected. A background in the classics prevents the historian from accepting the currently fashionable term “patriarchal” and makes her prefer “paternalistic.” As she says, “the South was not ancient Rome,” in which the patriarch had the right to dispatch wife, children, or slaves at will. Short of that, however, the Christian paternalist of the plantation household ran a tight ship with a ready whip hand—and not in the slave quarters alone. Slave mistress shared with slave women the imposition of male dominance, but they experienced it and the household discipline in significantly different ways. Lines of race and class divided southern women deeply. Their common culture and sufferings did not necessarily make slave women or yeoman women “sisters” of big house mistresses.

So much for a chapter on theory which, its author says apologetically, some may find a bit heavy going. She is gracious enough to avoid theoretical and social science jargon wherever possible and to write plainly and intelligibly. To each new field in the historiography of worthy causes, however, has come to be granted at least one neologism (or at least a novel usage for an old word) as a sort of badge of independence. In this instance the word “gender” has been defended as “a useful category” for some purposes of historical analysis and has rapidly become a term to conjure with.1 It does have legitimate uses, but reiteration does not seem to enhance its magic or its appeal.

More appealing than gray theory is the vivid illustration and concrete evidence in which these pages abound. In her treatment of the complexities and controversies of slavery, master–slave and mistress–servant relations, and relations between the races, our northern interloper has turned apparent handicap into advantage. Told in native accents, even realistic accounts of these matters can be dismissed as romantic moonshine. With her regional and ideological credentials, however, the Yankee scholar fends off suspicion and fearlessly sets forth complexity and paradox. “Mistresses lived intimately with their female slaves,” she tells us. They lived together “in an extended personal circle—a real if also metaphorical family—with many of the slaves of the larger household.” Mistresses were far more intimate with slave women than with white women of the yeoman class. Mistresses were confronted with “the humanity of their slaves and with ties—often reaching back to previous generations—that bound them to those whom they held in bondage.” Moments of “intimacy, affection, and love for a slave” might serve to confirm a self-image of benevolence on the part of the mistress who owned her, but it was “a confirmation achieved without necessarily betraying a trace of hypocrisy.”

These relations overflowed with complexities. “Intimacy and distance, companionship and impatience, affection and hostility, all wove through their relations.” They might “exchange extraordinary kindnesses, gifts, and other expressions of what appears to have been genuine affection.” All of which could take place between a slave whose ears had been boxed or her bottom blistered and a mistress who, of course, had “license to interpret any sign of independence as impudence, impertinence, obstinacy. The slaves, we may be sure, saw it differently.” But how on the whole do the ladies as mistresses of slaves pass muster? “They emerge from their diaries and letters as remarkably attractive people who loved their children, their husbands, their families, and their friends and who tried to do their best by their slaves”—all this despite their solid support of a social system “that endowed them with power and privilege over black women.” What South Carolinian or Mississippian, whatever her scholarly credentials, could hope to get by with conclusions that flattering to slaveholders?

The ladies had more relations and duties than those relating to slaves. The southern household had both production and reproduction functions. A plantation that produced virtually all its own needs kept white as well as black hands occupied. With twenty-one children of his own and fifty-odd slaves, Katherine DuPre Lumpkin’s grandfather had needs enough to keep all hands busy on his large Georgia plantation. Basic food processing and preserving, textile production at the spinning wheel and loom, cutting, making, and mending garments for masters and slaves, health and housing care and tending required not only supervising but sometimes hand-soiling, back-bending labor. The number of socks darned, gloves mended, collars turned, and dresses refitted, not to mention the clothes, quilts, carpets, candles, soap, dyes, and lye made from scratch is staggering. For all that, slave mistresses and their kin “lived—and knew they lived—as privileged members of a ruling class,” and—so another of their historians is admonished—“slaves of slaves they were not.”2

Advertisement

Conventions defining the southern lady lacked the “passionlessness” attributed to their female contemporaries in the Northeast. Female sexuality was not denied their class in the South, and, contrary to conventional views, was sometimes restrained with difficulty. If women complained of “too many faithless husbands,” some of them were known to have had “extramarital affairs of their own.” One husband, reflecting on the code of honor, remarked, “If all men who have cause to be jealous, were to shoot a man in this city, there would be a very considerable mortality here.” Judging from the findings of the study under review, the marble goddess on a pedestal evoked by W.J. Cash in The Mind of the South was a creature existing in rhetoric only:

Whatever slaveholding women endured, there are no grounds for believing them to have been especially prone to frigidity and want of passion. The voluminous letters between husbands and wives, as well as their diaries…provide precious little evidence of sexual morbidity. To the contrary, those letters and diaries convey an impression of frequently loving relations that hint, even by the standards of that reticent society, at physical joy in each other, and of no lack of passion…. And if the marvelous letters of countless husbands prove anything, their men loved them for it.

If I may adapt an old male sexist chestnut to the purposes at hand, “In those days women were women and men were glad of it.”

Attempts by historians to match, in the treatment of the lives, thoughts, and passions of slave women, the thoroughness and completeness with which their mistresses are described are handicapped by sparse and often biased sources. None of those huge family collections of letters and diaries exists on the slave women’s side of the story. “Since almost no slave women left direct testimonies of their experience,” the author explains, “it remains difficult, if not presumptuous, to try to reconstruct their lives.” Surviving written testimony was often inscribed by whites or filtered through their perception. In later interviews of the 1930s with surviving slaves, the questions were usually framed and the answers recorded by white interviewers. Purely black sources often derive from folklore, with its fondness for tall stories. It could not have been easy to fashion from these materials an account of as much persuasiveness as this one manages to convey.

The slave women encountered in these pages are rather more independent, more prone to resist and fight back than those traditionally pictured. The percentage of advertisements for women runaways is much smaller than that for men, but that does not necessarily mean they were more docile or reconciled to slavery. They probably had more trouble than men in passing unobserved off limits, and they had responsibilities for children that men avoided. There were no “women’s” revolts such as were common in Europe and Africa and no significant American slave revolt that took a woman’s name or a female leader, or one in which they played a predominant or major role. But individual female resistance there was, some of it physical. We are treated to a number of bloody fights, precipitated by punishment, cruelty, brutality, or threat of it. Since the resisting woman in these stories invariably wins, whether her white assailant is male or female (one time the whipper himself got whipped and another time a woman threatened with sale chopped off her hand and “throwed the bleeding hand right in her master’s face”), we are prudently cautioned that some of these stories bear the marks of folklore embellished as they were handed down.

Less dramatic and more authentic, as well as more typical of the daily lives the slave women lived, are accounts of the work they did. Sarah Wilson was one of the “hoe-womens,” who often worked in gangs, “hoed, chopped sprouts [of cotton], sheared sheep, carried water, cut firewood, picked cotton, sewed.” Some women, like Mary Frances Webb’s grandmother, did even rougher work, “just like a man. She said it didn’t hurt her as she was strong as an ox.” Formidable figures, some of them, they won fame in big house and slave quarters, as well as a lasting place in legend and Old South romance. Female counterparts to the male stereotypes Sambo and Buck, encoding white images of black docility and aggression, were Mammy and Jezebel—each of the paired caricatures in both sexes a contradiction of the other.

As pictured here, slaves “did not suffer total alienation and depersonalization” that they are said by others to have suffered in Africa, and were able to “build communities in enslavement.” On the other hand, the durable and extended slave family, with deep bonds among the family members, that Herbert Gutman described as coming out of slavery is missing from this account.3 Slavery “stripped slave women of most of the attributes of the conventional female role” and “made a mockery of marriage and family life.” Fox-Genovese places emphasis on the absolute power of master over slave, backed by law, and the unchecked sexual exploitation of slave women by white masters, their sons, their overseers, and black drivers. Some elaboration of the subject follows, but the limited nature of it recalls a curious announcement in the author’s prologue: “Sexuality ranks high among the topics to which I have devoted little attention,” and this despite “a number of years of psychoanalytic training.” Her main reason appears to be “that the available sources and methods do not permit responsible speculation beyond narrow limits.”

Another bypassed opportunity worth noting is suggested by the absence of any sample of women from the plantations of black planters and black slave owners. They would have provided a way of “controlling the variable” of race in the relations between classes. Sources on them are much more limited, of course, but recent work of exceptional interest on rich black slave owners of South Carolina opened some possibilities. The authors found that all the members of the owning class were brown, all the slaves black, and between them there was “no shred of evidence…of racial affinity.”4

Two chapters of special interest are one bearing the title “Women Who Opposed Slavery,” followed by one entitled “And Women Who Did Not.” The former deals exclusively with slave women, the latter with women of the slave-owning class. Based upon the rich source materials and writings of slave-owning women are studies of some remarkable women of the antebellum elite. Clearly the favorite of the author is Louisa Cheves McCord, dear and much admired friend of Mary Chesnut. Poet, playwright, political economist, the author of a tragic drama, Caius Gracchus, Louisa McCord was the true Roman matron that the sculptor Hiram Powers caught in his portrait bust of her in 1850. She sacrificed family and fortune for the South’s cause, remained an unwavering defender of slave society and all its institutions, and was known to her friends as “Mother of the Gracchi.” Her view of motherhood as “women’s true vocation” is said to be “inseparable from her theories of class and race relations.” Stern adherence to laws of history and logic of class interest earns the following tribute from her admirer, a modern feminist and Marxist:

Louisa McCord unflinchingly accepted the priority of historical over personal claims…. Loyalty to southern society led inescapably to the defense of slavery, which led inescapably to the subordination of women to men. Social order stood or fell as a whole.

And no bourgeois nonsense about it.

Counterposed to this paragon of duty and logic and fidelity to laws of history is her friend Mary Chesnut, another South Carolinian of even more wealth, more slaves, and more powerful political connections. She was also a gifted writer, whose work was posthumously to gain fame after McCord was forgotten. Yet in these pages Chesnut never wins the respect, praise, and admiration lavished upon McCord. She receives more space and attention than other women, is admitted to be “skillful, urbane, and sophisticated,” and “the richness and fascination of her diary” are conceded. But there is always something wrong, something missing, something disingenuous about her. For one thing she reverses McCord’s priorities and places personal above “historical” claims. She is a case of arrested development, halted at the “belle” phase of southern womanhood, given over to self-aggrandizement by means of “charm” and never passing on to maternal responsibilities. She never bore children, bitterly bemoaned the fact, and in spells of misery took to opium.

Mary Chesnut was ambitious, and not only for “authorship in the grand manner,” but also with “a sizable dose of the ambition that McCord so deplored in politicians and belles.” She took keen delight in pleasing, charming, and being the center of attention in excelling as woman. But beyond that, she aspired not merely to power over men, but to the power of men. She confessed in her diary that she believed she could run the stupid war better than the stupid generals in command. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese believes that “she was torn between her ambitions as a belle and her more repressed ambitions to equal men,” and goes so far as to say that “had she been able to choose, she would—I suggest—have chosen to follow that quintessential hero and belle, Elizabeth I, in her announced role of Prince.”

Exceeding Chesnut’s ambition and all her other shortcomings as sources of annoyance, and as reasons we are offered to suspect her disingenuousness, are her numerous pronouncements as one of the few “quasi abolitionists and quasi feminists” among slave-holding women, and in the extremes of her rhetoric not even typical of them. Chesnut’s doubts about and distaste, and even revulsion, for aspects of slavery (“a monstrous system”) and male dominance (“no slave, after all, like a wife”) are not denied, but all sorts of reasons are found to “raise questions about the views she claimed to hold.” First, “perhaps she did not intend her scathing words in an abolitionist or feminist spirit at all”; or perhaps “unhappiness about other matters brought slavery to mind as a target for the displacement of other grief”; or “rebel that she was,” perhaps she advanced shocking views “out of a spirit of contradiction”; or “to present personal complaints as social judgments”; or merely to gain the attention her vanity demanded. And finally, for good measure, “Perhaps she should simply be understood as an anomaly—charming and talented, but no less an anomaly.”

As for those whose response is vive I’anomalie, the author would “take respectful exception to the attempt of learned friends and colleagues” who are inclined to make of Chesnut “a significant measure of protofeminism and protoabolitionism.” Presuming to be among “friends and colleagues” so admonished and anonymously targeted, I feel obliged to take a few respectful exceptions on my own. But first I acknowledge that I find much with which to agree in this analysis of pronouncements by Chesnut on women and slavery. Her cry of “Poor women! Poor slaves!’ constituted, not a call for emancipation and equality,” and I agree that it is more of “a lament for the human condition.” Surely much can be said for relating her outbursts on these subjects to her personal anguish and frustration. In speaking of her “abolitionist leanings,” I disavow any intent to equate her with her fellow Carolinians the revolutionary Grimké sisters, who defected to the North and set Yankees back on their heels with their radicalism. None of that in Mary Chesnut. Her views on race were, in the main, those of her time and place and could not pass muster today, nor could her brand of feminism, even though quite heretical in her time. But little is to be gained by applying current standards to the previous century. I have no desire to embarrass modern feminists in presenting them with a mid-nineteenth-century heretic from darkest slaveholding Carolina as a prototype or progenitor.

Before we dismiss Chesnut as an irrelevant anomaly or a faker, however, it is only fair to hear her on her heresies.5 She interwove them constantly, equating wives and women generally with slaves—in part as a rhetorical device for expressing her outrage against the patriarchy. “All married women, all children and girls who live in their father’s houses are slaves,” she declared. Their plight was no better. Deprived of their liberty, their property, their civil rights, and equal protection of the law, they were bought and sold, humiliated and reduced to abject dependency. And men of the master class, despite their sexual abuse of black slave women, “think themselves patterns—models of husbands and fathers.” On the evils of slavery itself, Mary Chesnut went further than any contemporary of hers in the South and further than the great majority of antebellum Northerners. Her declaration in 1861 that “Sumner said not one word of this hated institution that is not true” is the rough equivalent of a Rockefeller heir saying twenty years later, “Marx said not one word,” etc. Her declarations of hatred for the institution began when she was nineteen, were repeated again and again, and not only in her diary. She greeted the end of slavery with “an unholy joy.”

None of her views, of course, was the slightest threat to slavery or the benefits she derived from it, and she could contradict herself on this and other subjects. Another recent critic of Chesnut has observed that, “like Thomas Jefferson, she continued to benefit from the system, while enjoying the luxury of abhorring it.”6 A matter of taste, perhaps, but I prefer the slaveholding Jefferson who denounced the institution in unforgettable words to the slaveholding John Calhoun who celebrated it as a “positive good,” just as I prefer Mary Chesnut to Louisa McCord. Must the critics of a system necessarily be denied integrity because they are privileged beneficiaries of the system they criticize? Modern instances to the contrary include critics of two of the most powerful and oppressive regimes of the twentieth century who have been highly privileged beneficiaries of those systems, and yet have lately emerged as leaders with promises to end what they describe as intolerable error and oppression. It is even possible to imagine Marxist critics of a capitalist system enjoying its benefits, security, and privileges without forfeiting claim to the integrity of their convictions.

Trying to balance the preponderance of attention given to white slaveholding women, Fox-Genovese concludes with a chapter on a former slave, Harriet Jacobs. Hers is a moving story of oppression, flight, and eventual escape, but the telling is severely handicapped by the nature of the source. The present account is based on a book written by Jacobs under an assumed name to protect relatives and with an undetermined amount of fictional license. It is therefore sometimes “difficult to determine how faithfully it reflected Jacobs’s own feelings,” and some incidents “strain credulity.” Moreover, it is “written in the flowery style of middle-class domestic fiction” and cast “in the rhetoric of true womanhood.” Given the great sparsity of direct testimony left by slave women, it was probably the best that could be done under the circumstances and no fault of the author that this results in a weak ending to a strong book. It is, after all, the strengths and not the weaknesses of this book that deserve emphasis and make it a worthy achievement.

This Issue

December 8, 1988

-

1

Joan W. Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” American Historical Review, 91 (December 1986), pp. 1,053–1,075. ↩

-

2

The reference is to a chapter entitled “Slave of Slaves” in Catherine Clinton, The Plantation Mistress: Woman’s World in the Old South (Pantheon Books, 1982). ↩

-

3

Herbert G. Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750–1925 (Random House, 1976). ↩

-

4

Michael P. Johnson and James L. Roark, Black Masters: A Free Family of Color in the Old South (W.W. Norton, 1984), p. 141; and Johnson and Roark, eds., No Chariot Let Down: Charleston’s Free People of Color on the Eve of the Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 1984). ↩

-

5

Quotations that follow are from C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War (Yale University Press, 1981), or from Woodward and Elisabeth Muhlenfeld, eds., The Private Mary Chesnut: The Unpublished War Diaries (Oxford University Press, 1984). ↩

-

6

Drew Gilpin Faust, “In Search of the Real Mary Chesnut,” Reviews in American History, 10, No. 1 (March 1982), p. 57. ↩