For some Reagan aides, resignation was just an opening bid. General Haig, who learned (imperfectly) the art of resigning from Henry Kissinger, mismanaged his series of resignations so that finally—what in Kissinger’s scheme is never supposed to happen—his offer was accepted.

George Shultz, Haig’s successor, put himself on a ration of resignations; his two known ones were turned down. Where he might have been accepted—on the Iran affair, when Casey wanted him out—he resisted any impulse to resign.

Bud McFarlane, according to Donald Regan’s new book, seems to have resigned inadvertently, or one time too many:

On December 2, reports appeared in the press that Bud had called on the President in Los Angeles and offered his resignation. The President’s response must be described in the tortured language that suits Reagan’s style best: the President had not refused to accept it. Whether McFarlane, who had hinted at resignation on other occasions, was surprised by this result, I do not know.

Regan himself knew that resigning, done right, was the way up, not out. Infuriated by a leak of his remarks at a cabinet meeting that came, he believed, from James Baker at the White House, Regan, in November 1981, sent over his letter of resignation as secretary of the treasury. Reagan called him and said, “If you go, I’ll have to get my hat and go with you.”1 At last, Regan had accomplished what all such resignings were supposed to effect—he had caught the President’s attention, which came in intervals of varying brevity.

Up to the time when he used a threatened departure as his mode of advance, Regan was frustrated. Appointed secretary of the treasury by a man he had met only at two fund-raisers, he did not see Reagan during the transition period; he got no instructions from him when he took office; he was not granted a private discussion with him; and when he addressed him in group meetings, he got no questions or specific responses. “In the four years that I served as Secretary of the Treasury I never saw President Reagan alone and never discussed economic philosophy or fiscal and monetary policy with him one-on-one.” Left without guidance from the top, Regan had his aides collect Reagan’s public statements on the economy, and found out from them what policies he should be implementing. Inside the government, he had to go outside it to find what was expected of him. You can only read the billboard on your house if you go outside to read it—out was the only way up.

Regan’s experience was shared in other departments of Reagan’s government. Haig’s description of his isolation in the State Department is similar to Regan’s, as is Terrel Bell’s description of his post in the Department of Education. Only David Stockman at OMB was busy with a plan of his own, which the President approved because he did not understand it, a situation Stockman preferred.

Regan, proud of his CEO past at Merrill Lynch, chafed at being left in Stockman’s “backwash.” Stockman dealt with James Baker and his aides in the White House, cutting Regan out. Then, “oddly enough,” as he puts it, “it was Nancy Reagan who brought me into the process—through a back door.” Mixing private and public business in her customary manner, Mrs. Reagan had sent Regan a letter from a friend of her stepbrother’s who was worried about the state of the savings and loan business. When she followed up the letter with a phone call, she asked about the future of investments, and Regan said that interest rates must come down:

“You should tell Ronnie that—quickly,” Mrs. Reagan said. “I’ll have Mike Deaver put you on the schedule to see him.”

Again I was surprised. The President’s wife was going to tell the Deputy Chief of Staff to put the Secretary of the Treasury on the President’s schedule so the Secretary of the Treasury could tell the President of his views on the economy?

That—or something like it—is what happened.

Regan did not get an appointment with the President, but he did get a phone call from Camp David, at the prodding, he suggests, of Mrs. Reagan.

Given this opening, Regan followed up with his threat to resign, then bargained his way into Reagan’s inner circle by exchanging jobs with James Baker, who was chief of staff at the White House—an exchange that depended on the early support of Michael Deaver (because of his closeness to Mrs. Reagan), but one that the President was informed of only at the end of the process, and one that he accepted without discussion.

Thus admitted to the inner councils of the government, Regan found himself given as little direction about policy as he had received in his isolation at the Treasury Department. Having gone outside to fight his way inside, he found nothing there. Beneath the manufactured intimacy of Reagan’s public appearances there was only the manufactured intimacy of his private life—the jokes prepared to begin each day, the birthday presents given to members of the staff (once on the wrong day, but everyone pretended it was the right day to please the President as he pleased those around him), the careful reticences people observed to avoid the embarrassment of embarrassing a president. The reticence began with Reagan himself, who rarely ventured an opinion even in his circle of intimates, and who was struck mute by evident knowledge in an interlocutor:

Advertisement

Reagan was habitually shy and withdrawn in personal meetings with people he did not know well, especially if the visitor happened to be present as an expert. In such circumstances jokes were usually omitted and the President would listen intently but seldom speak. He was reluctant, even, to meet with some of his speech writers because they were comparative strangers to him. Sometimes, when the subject was esoteric, Reagan would be particularly passive, and as we grew to know each other better I would occasionally ask him why after the meeting was over. It would usually turn out that he had hesitated to ask questions because he did not wish to seem uninformed in the presence of people he did not know well.

This hesitation to commit oneself to an opinion was contagious. Though the President finally reached the stage of asking Regan some questions, he “would apologize for asking a basic—sometimes even a startling [sic] basic—question about an arcane subject.” Rather than put the President through this ordeal of apology, Regan frequently says he failed to press Reagan for explicit direction. Even when, as chief of staff, he presented a long-range economic plan for the nation, he did not challenge the President’s failure to alter or even to comment on the complex program he was accepting:

Perhaps I should have quizzed him on tax policy or Central America or our approach to trade negotiations; certainly my instincts and the practice of a lifetime nudged me in that direction. But I held my tongue. It is one thing brashly to speak your mind to an ordinary mortal and another to say “Wait a minute!” to the President of the United States. The mystery of the office is a potent inhibitor.

If even the voluble Regan became a courtier in this dance of reciprocal deferences, imagine the effect of such eerily tacit exchanges on people less brash. “Few will openly concede that they are not in the confidence of the Chief Executive, that they do not know his mind or support his goals.” Thus we are given the spooky picture of high officials gravely nodding together at they knew not what, under a liturgical joviality that others orchestrated and Reagan depended on:

Reagan’s personality and his infectious likability are founded on a natural diffidence. He hesitates to ask questions or confess to a lack of knowledge in the presence of strangers—and thanks to the way his staff operated, nearly everyone was a stranger to this shy President except the members of his innermost circle.

And that circle was engaged, most of the time, in a protocol of pretended consultation. It was like conversing with a large and handsome billboard.

On the occasions when people tried to draw the President into detailed discussion, he performed ill because he was “overprogrammed,” that interesting euphemism Regan shares with Mrs. Reagan. The President’s unfortunate Louisville debate with Mondale in 1984 was the result of David Stockman’s attempt, at a rehearsal for that meeting, to let his leader in on some of the figures he had been juggling; and Reagan recovered under Roger Ailes’s theatrical preparation for the next debate, which provided him with a script of quips instead of drilling him on facts. Reagan ran into the same problem of information overload, his information threshold being low, in his first (and for a long time his last) press conference on the Iran scandal. John Poindexter was so urgent in supplying him with precise evasions on the subject that the President stumbled into just the denials—for example, of Israel’s role—he was supposed to avoid.

The President, says Regan, disliked confrontation more than any other person he has met; shied from unpleasantness; took refuge in his routine, which he hated to see disturbed. “Never did he issue a direct order.” He preferred to be ordered on his rounds by his sacred schedule:

His daily schedule was the centerpiece of his life. The scrupulous way in which he observed it, checking off each event with a pencil after it ended and preparing himself for the next, gave his life a regularity and a tangible measure of accomplishment that evidently was deeply pleasing to him. He seemed to feel that his schedule set him free: more than almost any other person in the world, he knew exactly what to expect all day long, every day.

In this satisfying order of events, the most preferred were the ceremonial, where Reagan’s every line was scripted, his toe-marks chalked to put him in the best light (and at the farthest remove from the press). The ceremonials of affability seemed more spontaneous than life itself, and in some measure replaced it. All the vitality of the White House was drained into the vibrancy of the President’s public appearances, sucked into that one most vivid and important asset of administration, leaving a vacuum around it where people gasped for air. The people who were silent then remember themselves as shouting at the President’s deaf ear—sound does not carry in a vacuum. This is the real explanation for the bitter memoirs that have been emitted from those airless surroundings, where the show of joviality promised community and denied it.

Advertisement

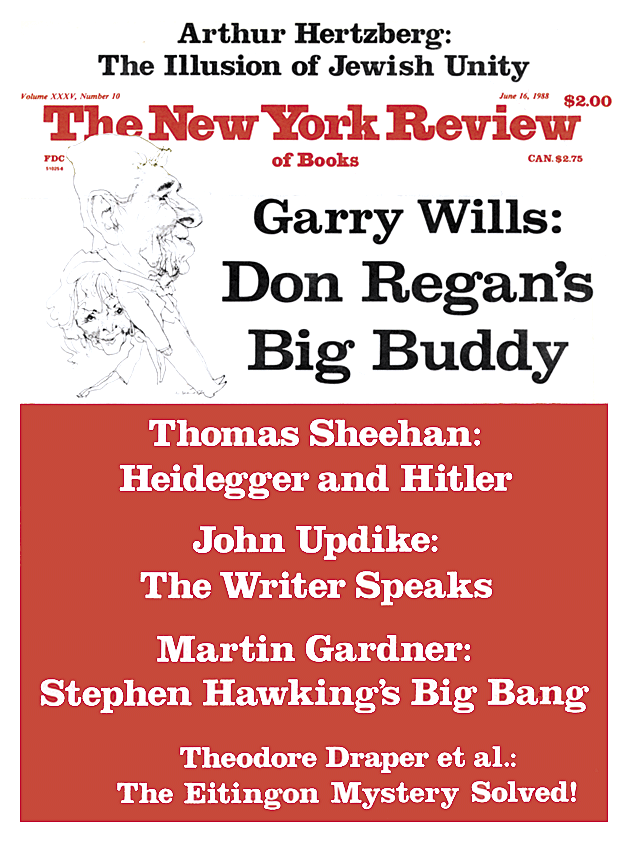

When Orwell’s Winston Smith enters his apartment house, on the opening page of 1984, the first thing he sees is a Big Brother poster at the end of the hall “too large for indoor display.” It does not fit inside. It belongs outside. But there is one on every landing as Winston’s lift takes him up to his own floor. Already Orwell has suggested the inversion of public and of private life in the modern world. Out on the streets, the poster is the only vivid item in scenes otherwise drained of color. Reagan is not as sinister as Big Brother—he suggests, instead, a model for Big Brother in Orwell’s earlier novel, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, whose hero resists conditioning by a huge poster of “Corner Table”—a man enjoying his Bovex. “Corner Table” has the insider’s bullying bonhomie, and he haunts the dreams of Gordon Comstock. Reagan has become the ultimate product of our consumer society, Corner Table, our public buddy, with his billboard accessibility and uncomplicated message, an irresistible endorsement of himself (whatever that is). This product makes us feel good; it is not fattening, demanding, or expensive. You do not even have to go to the trouble of buying it. It buys you.

Regan, who denounced his predecessors in the White House for reducing politics to entertainment, became himself a cultivator of this “Big Buddy” image of Reagan. He took lessons from Deaver in timing his jokes and his pats on the back to keep Reagan in performance trim. In this he initially collaborated with Mrs. Reagan, who was not as loath as her husband to give direct commands: “What we’re going to have to do is prop up our guy here,” she told him. “Our guy” is the right tone for Big Buddy.

[The President] was subject to puzzlement and self-doubt in the absence of public approval. In extreme cases, such as the storm of blame and suspicion that surrounded the Iran-Contra affair, he might be virtually immobilized. Much of Mike Deaver’s work, and a great deal of my own after Deaver left, had to do with organizing a psychic atmosphere in which the President was routinely made aware of the good things that were being said about him by people in their letters and in public-opinion polls, by the press, and by other politicians. A good review always bucked him up and a bad one generally saddened him…. Certainly his wife’s preoccupation with image had much to do with her realization that he needed praise.

It was precisely because he was hard at work on the atmospherics of Reagan’s theatrical performance that Regan clashed with Mrs. Reagan, the supreme authority on her husband’s needs as a performer. If, when Regan penetrated the inner chambers of power, the oracle was mute, the sibyl was not. She was the banisher of unpleasantness from Ronnie’s presence, the remover of embarrassments, the muter of discord. Regan compares her to Livia in Robert Graves’s I, Claudius, a woman who prefers her poisons slow and wasting; but there was little delay in Nancy’s efforts to get rid of Ray Donovan, William Clark, Helene Van Damm, Patrick Buchanan, Richard Allen, William Casey, and Don Regan himself. It is a distinguished hit list, and a testament to the good taste of the one who drew it up. Livia, we should remember, was such a good politician that her husband, Augustus, was careful to put his conversations with her in writing,2 and her son Tiberius “avoided frequent meeting with her, or any prolonged conversations in private, not wanting to acknowledge the guidance he occasionally submitted to.”3 Even her great grandson Caligula remembered her as “a Ulysses in drag.”4

Donald Regan, Mrs. Reagan’s most publicized victim, can hardly be expected to admire her political taste, though he grudgingly admits some of her skills. He gives us Rashomon retellings of their most famous spats—the helicopter Regan was denied, lest it suggest that his time was more valuable than hers; Regan taunting Nancy through the press when she promoted a Charles Wick protégé with a Nazi Youth past; the phone call they each raced to end by hanging up first.

At least Nancy Reagan did her job well. No more was expected of her than to keep Corner Table bonhomous, our national Big Buddy. Regan also tried to do her job, badly, while neglecting other things that were expected of him. He repeatedly calls the President incurious about important matters, yet says that he—Regan—was content to be ignorant of the national security activities of Bud McFarlane, a man given great responsibilities, and a man Regan deeply distrusted. At a famous moment in Geneva, Regan interposed his head between Reagan’s and Gorbachev’s for a striking photograph; but when the same head came between Reagan and McFarlane at that same meeting, it was not functioning, as Regan himself declares—he paid only partial and uncritical attention to the details of a complicated arms exchange McFarlane was describing while the President indulged in that earnest attitude of listening that passed for presidential decision making. Regan, the great manager, did not manage. Others, principally William Casey, knew how to get the President’s active assent in ways that Regan never mastered. The Tower Commission laid too much blame on Regan, and too little on Casey and others. Regan was more interested in battling Nancy over the later “presentation” of the Iran deal than in the initial wisdom of that transaction.

But what should we make of Nancy’s astrologer? Not much, I think. Regan says that the “Friend” in San Francisco interfered in the nation’s business when she made it impossible for the President to discuss Iran for months. But Nancy Reagan had clearer signs than the stars, ones she read daily and with great acuity, to indicate that Reagan was not ready to face the nation and go through that labyrinthine affair after his disastrous November press conference. The astrologer was a handy device for not voicing the real reason for Reagan’s period of hiding—he was inadequate. He often is, when the scene has not been prepared and his performance polished. Nancy’s Friend was a convenient way for her to avoid saying that the President was not up to his job. She would never say that to the President himself. Surely she would not say it to Donald Regan. The Friend made that unnecessary. Besides, in supplying auspicious days as well as ominous ones, the Friend helped create that mood of good things happening around the vibrant Big Buddy that was so important to his performance. The Friend was Nancy’s masterstroke, her great excuser in the stars, the proof that Ronnie’s faults are not really in himself, but in his aides.

Nancy Reagan probably believes in astrology (as in her husband)—that, too, is convenient for her. But she is ready to use more earthly “influences” to accomplish her mission. Sometimes that meant using her husband, sometimes it meant going around him. Even Nancy Reagan had to go outside the White House to get things done inside. When reaching out to the California publicist Stuart Spencer, or even to a Democrat, Robert Strauss, she was peeking around the billboard herself, admitting to the emptiness behind it. Does Big Buddy actually exist? Only Nancy knows. And sometimes she looks doubtful.

This Issue

June 16, 1988