The class imagery of the presidential campaign is important but peculiar. George Bush has only recently looked as if he might escape from the image of the invisible “Poppy” from Skull and Bones, lampooned so wittily in Doonesbury. Bush’s image is odd not simply because of his well-known war record and his fling as a Texas entrepreneur but also because his family is apparently only the third richest of the four in the race. Bush says that his personal net worth is about $2 million. This does not include the assets of his extended family, but there is no indication so far that he is the heir of a great fortune. Dan Quayle says that his personal assets total less than $1 million, but his family’s trust holdings in the Central Newspapers, Inc., chain in Indiana are reported to be worth more than $400 million. (The trust was established by Quayle’s grandfather, the newspaper magnate Eugene Pulliam. Under its terms, Quayle cannot inherit the principal assets of the trust. But he will eventually receive a share of its income and could inherit other significant blocks of newspaper stock.) Spokesmen for Lloyd Bentsen, whose father built a land-development empire in the Rio Grande valley of southernmost Texas, say that they will “not dispute” reports that Bentsen is worth more than $10 million. Only Michael Dukakis, the son of immigrants, is poorer than Bush, but not by much. His personal assets are reported to be worth about $500,000, and he stands to inherit about $1 million more.

Of the four men Bentsen is the one whose personal bearing seems in keeping with his background and balance sheet. Bentsen acts like what he is: a confident member of a provincial aristocracy, accustomed to great power in his own region (he was more or less anointed to a seat in Congress when he was in his twenties) but unmistakably a product of one region, not of a national upper class. Bentsen went to college at the University of Texas, not at an Ivy League school. This is a mark of seriousness about success in Texas politics and business, whether for rich boys like Bentsen or poor boys like John Connally. After a few terms in Congress, Bentsen got bored, returned to his base, and made his own fortune, in Houston, in the insurance business, where his father’s financial backing, name, and connections were of obvious help. The disagreements over policy between Bentsen and Dukakis are a somewhat obscure issue in the campaign, and Bentsen’s record as a water-carrier for business interests in Congress is an even more deeply buried issue that deserves attention. But Bentsen’s “character” is rarely debated, mainly because there is no mysterious discrepancy between background and behavior to be explained.

With all the others, something seems askew. Dukakis makes much of his frugal immigrant upbringing, but it’s as if he skipped a generation in the normal process of assimilation. His father, after all, had graduated from Harvard Medical School and become well established in Brookline by the time Dukakis was born. The classic immigrant struggle for education, white-collar respectability, and financial security was over before the second generation came on the stage. Quayle, who is on paper the most upper-class of all the candidates, a prominent member of a family that has been rich and influential for a long time, comes across as a familiar Middle Western fraternity type, hardly aristocratic. The controversies about how he got into law school and the National Guard have hurt him more because of what they imply about his own mediocrity and willingness to cut corners than as indications of his family’s dynastic might. And then there is George Bush, with his record of wartime courage and his heretofore unshakeable reputation as a wimp.

Nelson Aldrich’s Old Money greatly enriches the understanding of these incongruities, and many others concerning money, status, success, and respect. I say “enriches” rather than “clarifies” because the book itself is woolly, tangled, anything but taut and clear. It is plainly Aldrich’s life’s work—in the best sense of the term, as an attempt to examine the meaning of his own life as a fourth-generation inheritor of family money. It in no way resembles a book worked up from an outline or to satisfy a publisher’s contract. Rather, it appears to be the result of years of brooding and collecting illustrations on a simple theme. Aldrich moves constantly from one form of evidence to another and one theme to the next, returning most frequently to his own experiences—at St. Paul’s, at Harvard, and with his old-money relatives and friends. As a result, reading the book is like going through a steamer trunk owned by someone who is curious about everything—Aldrich’s distant relative Teddy Roosevelt, for example. It is a disorderly and sometimes confusing book, but a very, very interesting one. When I read the book a second time I found it more impressive and enjoyable—an indication that Aldrich has left some loose ends but also that his material is very rich.

Advertisement

Aldrich’s central theme is the conflict between two ways of thinking about money. One is New Money, by which he means something other than the pretensions of arrivistes like Donald Trump. He is talking, instead, about the fundamentally capitalist (and American) idea that money is an instrument of change. People will constantly rise and fall in society, and money is not only the indication of their success but also the means by which they enjoy the rewards they’ve earned. Aldrich gives a variety of names to this outlook—the “entrepreneurial imagination,” “Market Man”—but the essence of all of them is that life is fluid. Social order is made to be changed. Even values are fluid. Market Man unconsciously judges all things according to a market standard, and will be no more loyal, brave, self-sacrificing, and so on than the market dictates.

On the other hand we have Old Money, which is identified not by certain sums in a trust fund but by the values and behavior it evokes. Money in this view is not something to be made or spent but something that is; it somehow sits in the background of the family, imposing both privileges and responsibilities that have nothing to do with the market.

Wealth is seen as an estate or patrimony with a history and a posterity, literally or figuratively held in trust, and producing an income dedicated to specific social purposes…. Wealth in this view is a given, not something owned or possessed, which should be given on.

People born into Old Money start out with more than they “deserve,” by market standards—but if they absorb the Old Money ethic they’re also bound by certain moral and social obligations from which normal people are free. If they get the money but not the ethic, then, Aldrich says, they are not Old Money patricians but mere “aristocrats,” rich kids reveling in their privileges, Eurotrash.

This brings us back to George Bush. Aldrich mentions him only briefly (and dismissively), calling him a “traitor to his class” for running a campaign that “represent[s] a total surrender to the entrepreneurial [rather than patrician] imagination.” Aldrich spends less time on Bush than on Pierre “Pete” du Pont, because du Pont’s more aggressive entrepreneurial arguments made him a bigger traitor to patrician values. Here a tone of indictment enters Aldrich’s usually reflective prose:

Of the two, du Pont was perhaps the greater class traitor. He was certainly more aware of what he was doing, and did it better. There is not one area of public life, not one actual or potential public good, not one slice of the nation’s patrimony (except for its museums, perhaps, and a small part of the great outdoors), that Pete du Pont would not give over to the custody of entrepreneurs in free markets. It is almost eerie how this inheritor of trusts and other assets worth at least $3 million (the figure was grudgingly allowed to grow as his campaign went on) singled out dependency as the most sinister evil facing the nation. He might have pointed to greed and fear, but he didn’t….

Du Pont was a traitor to his class not because he presented himself as a conservative, not even because he presented himself as the candidate of virtue (conservatives usually do). Old Money is always politically conservative—patricians are conservative with respect to ends and means, aristocrats with respect to ends alone—and likes to think of itself as a party of virtue. Du Pont betrayed his class, rather, in presenting himself as a radical partisan of the marketplace and of the single virtue of toughness—“what it takes to make it in this world.” For all his trumpet calls to get tough with the Soviets anywhere in the world, he was also a candidate of fear. But the best sign of his class background was his extremism. In Pete du Pont, the American people caught a glimpse of Tom Buchanan running for office, weakness hidden behind a breastplate of righteousness, careening through other people’s lives while sure of the invulnerability of his own, his carelessness carefully packaged and marketed as “toughness.”

Yet one wishes he had given more attention to Bush as well for almost every detail of Bush’s background fits Aldrich’s scheme.

To begin with, the Bush and Aldrich families both demonstrate that American “old” money does not really have to be old, not as the rest of the world reckons time. The “best” American families of any given moment are often no more than two or three generations away from the shameless Trump-like pioneer who actually made the money. The Astors are the patricians of twentieth-century New York; they were the arrivistes of the nineteenth century. William F. Buckley’s grandfather was a sheriff in South Texas. As Aldrich says, “Americans typically want nothing so much as to make themselves new, an appropriate yearning in this New World. Old Money Americans simply want to make themselves new in the most radical way a New World can imagine, by making themselves Old.”

Advertisement

Aldrich says that his own life has been molded by the effects of Old Money—but the Aldrich money was not merely new but nonexistent a century ago, when the first Nelson Aldrich, a grocer in Rhode Island, first married a well-to-do woman, which helped him get into politics and make himself very rich. Like Lyndon Johnson half a century later, Senator Aldrich converted his power into money without doing anything detectable or indictable; Aldrich, however, made much more money. Later the family’s fortunes got a lift when the author’s Great-Aunt Abby married John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and his Great-Uncle Winthrop became head of the Chase bank.

Bush’s “old” money is cleaner than Aldrich’s but even newer. Near the turn of the century, Bush’s grandfather, Samuel P. Bush, ran the Buckeye Steel Casting company in Columbus, Ohio. The family fortune began there, as did its “tradition” of upper-class education. Samuel Bush sent his son Prescott to Yale, where he was tapped for Skull and Bones. But Prescott Bush went back to the Midwest, holding industrial jobs first in St. Louis and then in Kingsport, Tennessee, before moving to New England just before George was born in 1924. He ended up as managing director of Brown Brothers Harriman in New York. Aldrich says that one of Old Money’s most powerful social weapons is its appearance of “precedence”—of having always known certain friends, gone to certain islands for the summer, sent children to certain schools. This is the impression the Kennedys fostered with their “family compound” in Hyannisport; Bush’s estate in Kennebunkport conveys the same idea. But the clubs and resorts to which Bush has “always” gone came into the family only after his father moved east. Bush’s mother, Dorothy Walker Bush, had family money of her own, but it was also fairly new. Her father, George Herbert Walker, made his money in the dry-goods wholesaling business in St. Louis and then started an investment firm. Bush’s old money is much more recent than that of, say, the “housewife” Corazon Aquino.

The newness of Bush’s money fortifies Aldrich’s point—that money becomes “old” the instant that it imposes certain standards of behavior on a family. (In still-feudal societies like Corazon Aquino’s Philippines to say that someone’s money is not really old is a deep insult. One well-known “liberal” writer in the Philippines published a debunking biography of Imelda Marcos. Its nastiest blow was that while Imelda pretended to be an aristocrat, Cory really was: “Her jewels were truly heirlooms, not recent purchases from Van Cleef and Arpels…. She represented all that Imelda had ever aspired to.”) The Buckeye Casting money had barely settled by the time Bush was born, but the values were clearly in place.

The worthiest of these values, as Aldrich describes them, is the patrician sense of responsibility for preserving society’s patrimony, as it preserves the capital in its trusts. Aldrich says that this theme runs through the upper-class conservation movements at the turn of the century and the modern campaigns to “save” the economy by Felix Rohatyn and Peter Peterson, two New Money figures who are following the patrician tradition of trying to rescue the public from the consequences of its own excesses. At times the patrician impulse leads Old Money families into electoral politics, in a fashion epitomized by Prescott Bush. “It wasn’t until 1950, two years after I’d left for Texas, that Dad entered his first political race, at age fifty-five,” Bush says in his autobiography, Looking Forward, of his father’s decision to run for the US Senate from Connecticut. “It didn’t surprise me, because I knew what motivated him. He’d made his mark on the business world. Now he felt he had a debt to pay.” At the time, Newsweek quoted a “hardboiled political writer” as saying, “Pres had an old-fashioned idea that the more advantages a man has, the greater his obligation to do public service.” Bush says in his autobiography that “Dad was concerned about the future of the two-party system,” a fear that has rarely nagged nonpatricians. With this family background, it’s not such a surprise that when George Bush was shot down over Chichi Jima, his thoughts turned (or so he’s recounted) to “the separation of church and state.”

All of this half-implausible high-mindedness might have come straight out of Aldrich’s book. He says that the theme of “giving something back” or “giving something up” is not simply part of the familiar concept of noblesse oblige; it is the essential source of Old Money’s self-respect. Inheritors come into the world owing a debt that, by definition, they can never repay. The founder of the family fortune, their benefactor, is dead. By normal market logic, this is a compromising situation, especially in the land of self-made men. The only way inheritors can square their accounts with the world is to pass their gifts along, giving something back to the community and to posterity.

This is a noble concept. The trouble with it, as Aldrich shows, is that it often leads merely to a niggardly desire to preserve the family’s patrimony against the vulgar masses. But even when it is taken seriously it does not completely remove the problem of the inheritors’ moral standing. Americans envy and try to copy the style of Old Money life, Aldrich says—this is what Ralph Lauren’s ads are all about. But they also resent the unearned advantages and look down on people who did not make it on their own. “Every child of Old Money grows up under a barrage of verbal snowballs impugning his or her personal powers,” Aldrich says. Before World War II, St. Paul’s boys had a fey image. “Twenty years later, when I was there, St. Paul’s boys were still described in the same terms…by Groton boys, just as Groton boys were described in the same terms by Exeter boys, and Exeter boys in (almost) the same terms by high-school boys, and so on out into the farthest reaches of the entrepreneurial imagination, where all boarding-school boys are described, without distinction, as a bunch of fairies.”

Aldrich says that Old Money families offset these criticisms with distinctive virtues of their own—for instance, the emphasis on modesty and fair play. Thus we have George Bush as “Have-Half” at prep school offering his lunch to virtually anyone. For the last eight years, Bush has manifestly preferred to be considered weak and asinine than to seem in any way disloyal to his President. This is every vice-president’s predicament, but Bush has been more thoroughly stoic about it than anyone else in recent memory. Owen Wister, Theodore Roosevelt’s classmate in the academic and social sense, once wrote about the heroic TR in the Harvard boxing ring, where he had been walloped in the nose by a low-life opponent after the bell rang. Teddy assured the crowd that the man must not have heard the bell, and walked over to shake his hand. On the basis of everything else he does, this is the behavior we might have expected from Bush—which is why his stabs at “kick a little ass” tough-guy talk are particularly jarring and disgusting. They’re disgusting because we know, even without reading Aldrich’s book, that Bush knows he’s not supposed to talk this way. “You’re talking about yourself too much, George,’ [his mother] told me after reading a news report covering one of my campaign speeches,” Bush wrote in his autobiography. “I pointed out that as a candidate I was expected to tell voters something about my qualifications…. ‘Well, I understand that,’ she said. ‘But try to restrain yourself.’ ”

In addition to cultivating these virtues, Aldrich says that young men from Old Money families (he talks very little about the women) typically undergo three “ordeals,” which, almost in a chivalrous sense, are ways of proving their mettle. One is the “school ordeal,” endured in stern New England preparatory schools. The second is the “ordeal outdoors,” epitomized by Teddy Roosevelt tracking big game, Bobby Kennedy rafting down the Snake River, prep-school students out for a summer of “real work” on a construction gang or tramp steamer. The third is the “ordeal under fire” in wartime, preferably as a volunteer, ideally as a knight-like fighter pilot, and failing that as a Marine. (This is one of the rare places where Aldrich seems to get a nuance wrong. He says that “as an ordeal the Marine Corps continued to exercise its sway over the upper-class imagination right through the Korean and Vietnam wars.” The Marine Corps may have had some power over the imagination during the Vietnam years, but not, so far as I could see at the time, over upper- or professional-class behavior. The two best-known patrician Vietnam vets are Donald Graham and Albert Gore, each of whom was an Army “information specialist,” not a Marine.

Here again Bush fits the pattern neatly. He underwent the school ordeal at Andover, the outdoors ordeal in West Texas, and of course the ordeal under fire in the South Pacific. John Kennedy (with John Hersey’s help) converted an objectively less impressive record into a powerful war-hero reputation. In general, Aldrich says, the Kennedys, once snubbed by upper-class Protestant Boston, have been brilliant in their use of upper-class imagery. (“Kennedys in politics, for example, like to present their ‘customary’ passage through Harvard as a sign, simultaneously, of Old Money status and New Money talent.”) Bush has never figured out how to use Yale and Chichi Jima as John Kennedy used Harvard and PT 109, and so, despite his virtues and his ordeals, he has been subject to jibes like the one that the Texas politician Jim Hightower made at the Democratic convention: that Bush was born on third base and thinks he hit a triple. Aldrich is not speaking of Bush in particular, but could be, when he writes, “For his class background (never mind wealth) to be seen as an asset, it must be shown that he has the stuff to walk on his own two feet.” Somehow, Bush has never crossed this threshold. This failure may be the clue to Bush’s otherwise inexplicable choice of Dan Quayle as his running mate. For the last eight years, Bush has coasted along with Ronald Reagan. For fifty years before that, he was someone who started out with every advantage on his side. If he can win now—without Reagan, and carrying the third-rate Quayle—no one can ever doubt that he did it on his own.

The overall tone of Aldrich’s book is elegiac. Aldrich concludes that America is not an Old Money culture, despite popular envy of the old rich, and that the values of loyalty, modesty, pietas, and so on are therefore doomed to decline. America is built on the principle of constant change and wide-open possibility; this is fundamentally at odds with the Old Money idea that each person has, from birth, certain privileges and responsibilities. “If the proper tense for Market Man is the future conditional, the proper tense for Old Money is the past perfect.” The most cherished Old Money institutions, Aldrich says, are the schools and clubs that are least like market-places—little family institutions where inheritors may “take refuge from the world of doing and simply be.”

Aldrich seems to me right about America’s nature, and sometimes convincing in his laments for non-market, patrician virtues. America needs Market Men to earn its living, he says, but it also needs the Old Money values to teach it how to live. And yet, I think that he sometimes puts the contrast too starkly and reveals more than he may have intended about his own view of democratic, market-minded America. As part of his case for Old Money, he tells us that:

Inheritors of wealth do not have to bluff, mislead, or mouse around in commodities markets. They do not have to offer people phony or trivial services on the service markets. They do not have to start businesses in any kind of market, indeed, and need not nurture the enterprises by lying to creditors, cheating on taxes, and deceiving bankers. They do not have to run any business by exaggerating the “quality” of the product.

Well, as Aldrich knows, a good many inheritors of Old Money have been more than willing to do all these things to increase their fortunes; and many Market Men—most, I suspect—don’t have to do them. Aldrich says that the terms New Money and Market Men refer to America’s wide-open culture, but when he uses them a picture of Ivan Boesky seems to be in his mind. Perhaps the problem is that Aldrich has defined this as a contrast of two visions of wealth. For most Americans, there is no chance of becoming rich, but the Market Man culture keeps the possibility of change open to them.

Ronald Reagan may seem a weak source of evidence on this point since so many of his cronies have been the skimmers and chiselers Aldrich describes, and without them Reagan would have gone nowhere. But Reagan himself has been popular not because he epitomizes New Money in the Boesky/Trump sense but because he is such a dramatic illustration of the chances of winning the American market lottery. Michael Dukakis is supposed to exemplify American opportunity, but he can’t compare with Reagan, who was washed up in his late forties and started a completely new career. His popularity, compared to that of any of the four now in the race, is evidence of how powerful that idea still is. Against such a show of mobility, claims for patrician values have no effect, and the patricians themselves, whose remaining enclaves Aldrich describes with such acuity, have neither the cohesion, the confidence, nor the conviction to change much of anything.

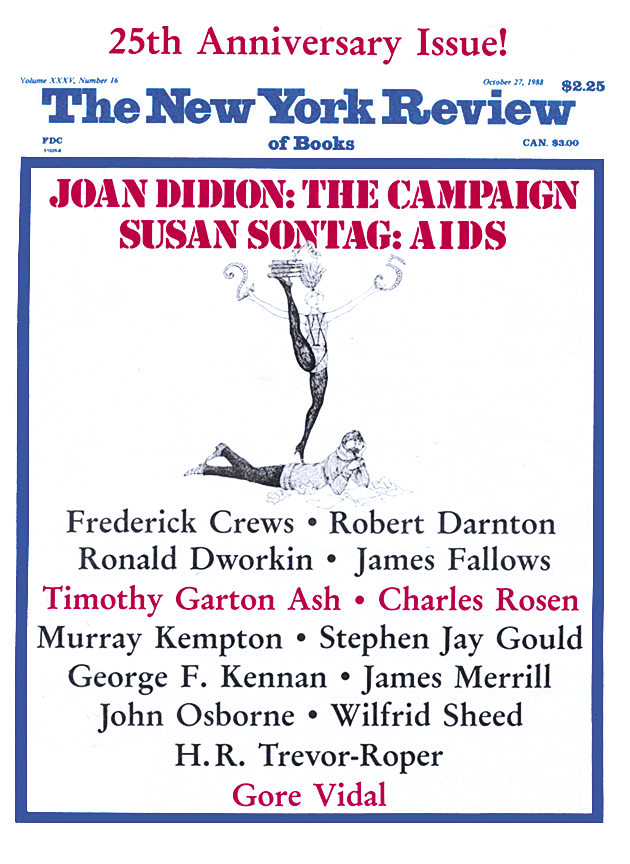

This Issue

October 27, 1988