1.

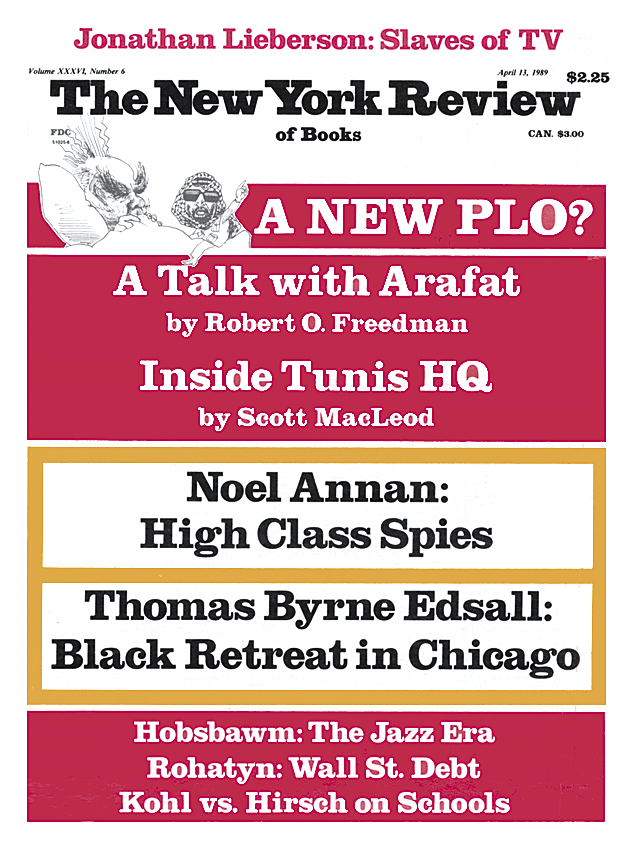

If the Palestine Liberation Organization has changed its ways as far as the United States government is concerned and has become an acceptable partner in discussions toward a Middle East settlement, then certainly no Palestinian guerrilla official better illustrates the PLO’s evolution than Yasser Arafat’s “special adviser” Bassam Abu Sharif.

Sharif’s reputation as the PLO’s most outspoken advocate of coexistence with Israel derives from the position paper he distributed in Algiers last June, stating that Palestinians wanted “lasting peace and security for themselves and the Israelis.” The paper quickly caught the attention of the State Department, European Diplomats, prominent American Jews, and many Israelis. A Palestinian official calls the paper “the main thing that broke the stagnant thinking within the PLO.” An American ambassador in the Middle East considers it the “first sign of the new Palestinian direction.”

What impressed some critics of the PLO was Abu Sharif’s unmistakably conciliatory tone toward the Israelis, and his acknowledgment that they had security concerns that could be accommodated by the PLO. To many who read the paper it seemed that a psychological barrier had been crossed. But Sharif also introduced important concessions—recognition of Israel along with its right to exist within secure borders and acceptance of United Nations Resolutions 242 and 338—which were eventually adopted in November by the Palestine National Council and clarified in December by Arafat’s speech at the United Nations General Assembly and his press conference immediately afterward.

Abu Sharif wrote last June that Palestinians wanted an independent state, and he appealed to Israelis for direct negotiations on a settlement that would “stand the test of time.” If Israelis questioned whether Palestinians regarded the PLO as their representative, he wrote, the PLO would agree to an internationally supervised election in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and abide by the results if non-PLO representatives were chosen. And if the Israeli army withdrew from the occupied territories, he added, the PLO would agree to a mutually acceptable transition period, in which the West Bank and Gaza Strip would be administered by an international force created by the UN.

While the proposals were a notable departure from the PLO’s previous official policies, they also appeared to be a radical break with the author’s own past. Until 1987, Abu Sharif had spent twenty years as a staff member and then as a leading official of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the Marxist-Leninist group founded in 1967 by George Habash and supported by the Soviet Union. The PFLP became the PLO faction most dedicated to Israel’s destruction and most ready to back up its words with deeds. The most visible exponents of Palestinian extremism during the 1960s, Habash’s men started hijacking commercial airliners in 1968 almost as a routine tactic.

Abu Sharif’s own involvement in terrorism became clear in September 1970, when at twenty-four he emerged as a spokesman—using the code name “Abu Bassam”—during one of the most spectacular terrorist operations before or since. PFLP guerrillas hijacked four airliners and ordered three of them flown to Dawson’s Field in Jordan. The terrorists held more than three hundred passengers hostage for a week, letting them go before blowing up the planes. The episode set off a civil war between Palestinian guerrillas from all PLO factions and King Hussein’s Bedouin army.

“Abu Bassam” went onto the planes and lectured the hostages about Palestinian suffering; he briefed reporters on the PFLP’s aims. In an interview during the hijacking with the American journalist John Cooley,1 “Abu Bassam” even justified holding women hostages—“Don’t forget that the Israelis have many Palestinian women prisoners”—as the only means available to Palestinians to exert pressure on powerful Western governments. He told Cooley that the PFLP, besides trying to bargain for the release of guerrillas in Israeli prisons, was trying to wreck the Rogers plan, the American peace proposal of the period, and “to abolish the state power of King Hussein’s regime now and get our enemies out of positions of power.” The hijackings made Abu Sharif persona non grata in the United States, Britain, Jordan, and some continental European countries.

Meanwhile, an ultraradical faction within the PFLP led by Wadi Haddad, which was later to break away from the organization, had begun using an even more appalling tactic: opening fire at European airports on groups of passengers bound for Israel. In May 1972, Japanese Red Army terrorists working for the PFLP machine-gunned twenty-six people to death at Israel’s Lydda airport.

As the official spokesman of the PFLP, Abu Sharif became a principal target of the Israeli secret service. On July 25, 1972, a book that had arrived in the morning mail at the PFLP office in West Beirut exploded in his hands. The explosion nearly killed him. His skin was scorched black from head to toe, the flesh was torn from his face and chest, and three of his fingers were burned down to stubs. His face and hands remain grossly disfigured today after years of plastic surgery. The package had been postmarked Bucharest and stamped “checked for explosives” by the Lebanese postal service. The book caught Abu Sharif’s attention because it had a large picture of Che Guevara on the cover. “The moment I opened it, in a fraction of a second, I saw what it was,” he recalls. “Inside, the book had been hollowed out and fitted with two explosive charges connected to some wire and small batteries.”

Advertisement

2.

I traveled to the PLO’s headquarters in Tunisia in February to see what I could learn from Abu Sharif, who is now forty-two, about the PLO’s current goals and future strategy and to ask him about his own career as a Palestinian guerrilla official. For a week we talked almost daily at his second-floor apartment in a white-washed villa, which he shares with a group of young Palestinian bodyguards and a cook. I was trying to find out why and how from being one of the PLO’s leading militants he had become one of its most prominent doves—a transformation so startling on its face that it might cause some to wonder how genuine it is.

Some clues to this transformation can be found in Abu Sharif’s upbringing. He was born in Kfar Aqab, near Jerusalem in 1946, two years before the end of the British Mandate. In 1951, his family, which included eight other children, moved to Amman, where his father became the manager of the Arab Bank. Abu Sharif’s parents were muslims, although he never became a strictly observant Muslim himself. He was sent to a French-language Christian school and eventually married a Maronite Christian woman from Lebanon (who still lives in their apartment in West Beirut with their two young children).

Although Abu Sharif grew up in a big house in Jebel Webdeh next to the American embassy, he went out of his way, he told me, to become friends with Palestinian children from the squalid refugee camp down the hillside. At the time, he enjoyed the privileges of a banker’s son; as a handsome, likeable teen-ager he came to be close friends with the princes and princesses in Amman whose Hashemite monarchy he would later try to overthrow.

Abu Sharif told me something of the circumstances that, he said, seemed to lead him down a militant political path. Along with his brothers and sisters, none of whom is in the PLO (and two of whom are American citizens, living in Illinois and Ohio), he began thinking politically around the age of ten, when his father tuned in to Cairo radio to hear the speeches of Gamal Abdel Nasser. Early on he felt a sense of grievance against the Western powers for harming the interests of Arabs and particularly Palestinians. But he became active in politics only after 1963, when he started attending his father’s alma mater, the American University of Beirut, to take degrees in chemistry, biology, economics, and business administration, and joined the Palestinian Students Union. Then two events happened that determined the direction of his life for the next twenty years: he met George Habash, head of the Arab Nationalist Movement, and the Arabs were dealt a humiliating defeat by Israel in the 1967 war. Habash, a young, dashing, and intelligent Palestinian leader, a Marxist from a Christian family, was then more prominent among Palestinians than Yasser Arafat. Habash dissolved the ANM and founded the PFLP. Like many other young Palestinian intellectuals from the university, Abu Sharif signed up. “If I had met someone else first,” he reflected, “I might have joined another group.”

Up to a point, Habash’s group suited Abu Sharif well. Terrorism aside, the PFLP became the second most important faction of the PLO, after Arafat’s Fatah. That its members included well-educated Marxists gave the group a certain cachet that Fatah, with its gunmen from the refugee camps, did not have. Abu Sharif rose quickly, becoming the group’s official spokesman at twenty-five when his immediate boss was assassinated by a booby-trapped car. His own terrible in juries and miraculous survival have given him a mystique in Palestinian circles. Throughout the 1970s, Socialist governments from Prague to Beijing received him and other PFLP officials as distinguished visitors. If he ever became bored with the PFLP’s revolutionary slogans—he told me he never subscribed with any enthusiasm to the Marxist theories of proletarian revolution incorporated in the PFLP’s program—at least no other PLO group was making better headway in “liberating” Palestine.

In 1982, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon jarred Abu Sharif as well as most other Palestinian officials. General Sharon’s war was intended to wipe out the PLO and nearly succeeded. The controversy over how to deal with the PLO’s predicament was one of the main issues that eventually caused Abu Sharif’s break with Habash.

Advertisement

Abu Sharif, who had become friendly with Arafat beginning about 1973, agreed with the new strategy that the PLO leader was working out as the PLO was being forced to leave Lebanon. With the PLO’s fighters being scattered all over the Middle East, Arafat decided to explore the possibility of peace negotiations with Israel. If nothing else, Arafat believed, this would keep the PLO alive on the international scene and enable the badly weakened organization to play the Arab states against one another, thus giving the PLO some degree of independence. Habash, for his part, felt that the PLO had more to gain by aligning itself with Syria’s hard-line position and maintaining a base in Damascus, which was closer to Jerusalem than Arafat’s new head-quarters in Tunis.

Soon Abu Sharif’s worst fears were realized. The Syrian president Hafiz al-Assad mounted a campaign to crush Arafat and take control of the PLO. In 1983, as Arafat traveled around the Middle East telling Arab governments including those of Jordan and Egypt that the PLO was open to peace talks, Syria incited a revolt inside the PLO and drove Arafat and his remaining loyalists out of Lebanon. Then during 1985 and 1986, Syria stood by and permitted the Shi’ite Muslim Amal militia, in an attempt to get rid of the PLO fighters who had infiltrated back into the city, to bombard Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut steadily for two weeks; the bombing resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties.

When Abu Sharif, who was then in Damascus, spoke out against Syria’s actions, the other PFLP leaders rebuked him, and President Assad’s regime attacked him. “One can understand Syria putting pressure on the Palestinians,” Abu Sharif said to me. The problem, for him, was that the Popular Front refused to take a strong stand against that pressure and did nothing to defend him when the Syrian government tried to intimidate him. First Syrian police impounded his car, ostensibly because it had Lebanese plates. Then when one of Abu Sharif’s American cousins arrived in Damascus for a visit, security men threw him into jail for forty-five days and whipped him on the back until his flesh split open. Finally, policemen showed up at PFLP headquarters with an order evicting him from his apartment without giving a reason. Habash chose not to challenge what was obviously a political attack on one of his own senior officials, and Abu Sharif began sleeping on a cot in one of the PFLP offices in Damascus. “I knew very well,” Abu Sharif said, “that the next step would be to shoot me.”

By then, Abu Sharif had resigned from the PFLP three times, frustrated not only with Syrian interference in Palestinian affairs but also with Habash’s evident inability to explore anything even hinting at a realistic path to a settlement with Israel. Each time he was persuaded to change his mind when Habash emotionally pleaded with him. “It is interesting how personal factors, like attachment to a certain period of history or the people you spent it with, can prevent you from resolving internal contradictions,” Abu Sharif said.

He finally broke with the PFLP in 1987. Defying a Syrian order confining him to Damascus, he secretly crossed the border in April and traveled to Algiers to attend a meeting of the Palestine National Council. Having kept Arafat informed of his feelings, he decided not to return to Syria and decided instead to join Arafat’s entourage. In July, the PFLP expelled him after he shook hands with Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak while traveling with Arafat. In November, Arafat made Abu Sharif his “special adviser.”

3.

The real catalyst for the PLO’s peace initiative was the intifada. Since the uprising began in the occupied territories in December 1987, about 400 Palestinians and 17 Israelis have been killed, thousands of Palestinians have been injured, 20,000 put under detention, and more than 100 had their homes destroyed. Abu Sharif could claim only to have had the sense to try to make the most of an opportunity presented by the intifada. “It gave us the chance,” he said. “It produced the most important regional factor, [one] that has changed a lot of things, such as pushing the Middle East back onto the list of priorities for the superpowers.”

In addition to putting pressure on Israel, the demonstrations and stone throwing in the West Bank and Gaza Strip sent a powerful shock through the PLO. The intifada forced Arafat either to come up with a political program that would seem workable to the Palestinians taking part in the uprising or, if not, to stand aside while the local leaders of the intifada turned themselves into the new representatives of the Palestinians. In undertaking a peace initiative that was strongly favored by the West Bank Palestinians, Arafat gained more political leverage over other PLO leaders and over Israel than he has ever had.

In March 1988, Abu Sharif began drafting a position paper that he originally had hoped to publish as an op-ed article in The Washington Post. “With the advancement of the intifada,” he explained to me, “it became important for the overall Palestinian struggle and for the intifada itself to present a clearly put, attainable program that would then lead the intifada and the [Palestinian] movement outside [the occupied territories].”

Abu Sharif drew on positions Arafat in numerous interviews had already been alluding to as well as on passages in Palestinian council resolutions. He also consulted Palestinian leaders in the occupied territories, including Faisal Husseini, head of the Arab Studies Society in East Jerusalem, who had been working on a peace plan in collaboration with dovish Israelis and American Jews. “Palestinians have been ready to have their own state side by side with Israel,” Abu Sharif told me. “Why not say it? I was sure there was a Palestinian consensus for it and that there was a growing feeling among Israelis that they want peace. I told the chairman that I wanted to write this article, and he told me to go ahead. He knew my thinking. I would not have done it if he had said ‘no.’ ”

The result can be seen as a culmination of the changes that Abu Sharif had been undergoing personally for several years. “Changes. Definitely there were changes,” Sharif told me. “We are alive. We think. We use logic. We deal with the new everyday. The necessities of daily life require a reevaluation of everything. What was true yesterday may not be true tomorrow. Political realism. That is the key thing here.

“I used to call for a democratic state [in Palestine],” he continued. “All of that’s true. I still dream of that. If the Israelis would accept the idea of living together with equal rights with Palestinians then we would form one big state, a more viable one, probably. But since the Israelis have expressed clearly that they don’t want that, the only realistic thing to do to attain peace is to have a two-state solution. I don’t mind people saying that Bassam has changed, if it is for the better.” He added, referring to the PFLP, “It is better than insisting on a position which had become completely unrealistic.”

When Abu Sharif looks back on the events that caused him to change his views, he recalls how Sharon’s bombing and shelling of Beirut reinforced his feelings that Israel was not likely to be defeated. At one point during one of the heaviest air raids of the siege, he turned to Habash and said, “See? They exist!” Abu Sharif told me that other political developments besides the intifada convinced him that the timing was right for a Palestinian peace initiative. One was that the US and the Soviets were showing themselves more willing than before to try to settle regional conflicts. Another was the end of the Gulf War. That enable Iraq, one of the most powerful Arab states militarily, to reemerge as a potential source of pressure on Israel as well as on Iraq’s archrival Syria—which had had a relatively free hand in sabotaging the diplomatic initiative Arafat had launched in association with King Hussein in 1985. (Later, last July, Hussein pushed the PLO further toward formulating an initiative when he severed his kingdom’s political and administrative links with the West Bank.)

During our meetings, Abu Sharif kept repeating the need for “realism.” Late one evening after a tense discussion with me about the occupied territories, he burst out angrily: “Shamir! I hate his guts! He is a criminal!” The next day, Abu Sharif told me that he did not exclude the possibility that Shamir could be the Israeli leader who would make peace with the Palestinians.

Abu Sharif decided to give his paper to journalists covering the Arab summit meeting in Algiers in June; the first story to report on it, by Geraldine Brooks of The Wall Street Journal, got wide attention. As diplomats began to take an interest in his proposals, Abu Sharif’s paper also set off a controversy within the PLO itself, not least because some top leaders were jealous of the international attention he was receiving. His strongest opponents were Abu Iyad, the number two man in the PLO, and Farouk Khaddoumi, the organization’s foreign minister. Abu Sharif’s proposals were debated in all the main bodies of the PLO—the Executive Committee, the Central Council, and the Fatah Central Committee. Some critics argued that it was the wrong time to be offering apparent concessions, while others complained that his statement should have been submitted to the Executive Committee for approval. Some opponents among PLO leaders angrily disputed Abu Sharif’s contention that the desire for peace was “shared by all but an insignificant minority in Israel.”

Abu Sharif said that he did not show the article to Arafat before releasing it, and in June Arafat refused either to endorse or to reject it. It was apparently Arafat, however, who headed off a move by some PLO leaders to issue a statement denouncing Abu Sharif’s paper as “one person’s personal view that does not represent that of the PLO.” After that, the paper became a basis for lengthy discussions, from which emerged the new PLO political program adopted at the Palestine National Council meeting in Algiers in November.

Since the United States opened a “substantive dialogue” with the PLO in December, Abu Sharif has put a great deal of effort into keeping up the momentum for negotiations. At his apartment in a seaside suburb of Tunis called La Marsa, I found him working eighteen hours a day. He spends much of his time on the telephone dealing with foreign diplomats and the international press, arranging meetings for himself and interviews for Arafat. Besides talking frequently to Arafat by telephone, Abu Sharif communicates by telefax with him and other PLO leaders regularly, sending and receiving reports on the intifada and other developments.

Abu Sharif was heavily protected by bodyguards. One night when we left for dinner at a nearby restaurant, he carried along a machine gun concealed in a plastic laundry bag printed with the words “Geneva Intercontinental Hotel.” “You drive,” he said, casually pointing to my rented Peugeot, “because then they won’t kill us.”

In my previous meetings with Abu Sharif in Damascus, Algiers, and Tunis, I had never seen him with bodyguards. He told me he had two concerns for his safety, the first being that Israelis would assassinate him. An Israeli hit squad that landed by sea had passed no more than a quarter mile from his apartment last April on its way to kill Abu Jihad, Arafat’s top deputy. But Abu Sharif said he was also worried about an attack by Syrian-backed Palestinian factions because of his part in the PLO’s diplomatic initiative. After his position paper appeared last year, three factions in Damascus issued an order that Abu Sharif be put on trial for treason in a Palestinian court. Though he is well known throughout the Palestinian world, Abu Sharif does not have a power base of his own. His standing with Arafat seems extremely high now as a result of his part in the peace initiative. But resentment of his recent prominence may have hurt his relations with other senior PLO leaders and aides.

The PLO leaders I talked to in Tunis were impatient for more progress, but I had never before seen them more confident about the future. This confidence was plainly a result both of the problems that the intifada has posed for Israel and of the political gains the PLO has made with its diplomatic initiative. When I asked Abu Sharif whether he thought that the Palestinians had ever been in such a strong political position, he replied, “Never.” This, he said, should be obvious. When I later met with the PLO’s foreign minister, Farouk Khaddoumi, he said, “The golden age of Israel is gone. It is our age now, the age of the Palestinian. If they are wise they will come to the international conference and negotiate peace before the train leaves the station.”

Besides getting the support of all twenty-two Arab countries except Syria and Lebanon, the PLO’s initiative has been well received in Europe. When I arrived in Tunisia, Abu Sharif had just returned from a diplomatic trip that had taken him to London, Paris, and The Hague and included a speech at the Oxford Union as well as meetings with leaders of Jewish organizations. In Whitehall, Abu Sharif was officially received by William Waldegrave, minister of state for foreign affairs, in the highest level meeting with a PLO official yet to take place in Great Britain. Palestinian leaders say they expect Greece, Spain, Italy, Portugal, and Finland will soon recognize the Palestinian state, whose establishment was declared by the PNC in Algiers.2 Many European countries have upgraded Arafat’s status. On his recent tour of European capitals, he was received as a head of state; in Madrid, for example, he was greeted by the king of Spain.

4.

I asked Abu Sharif what the PLO hoped would eventually be the outcome of its diplomatic and public relations offensives. He described a plan for a peace settlement that was more detailed than any I had previously heard from a PLO leader. The PLO, he said, wants the United Nations to convene a peace conference at which Palestinians and Israelis would negotiate Israel’s withdrawal from the occupied territories and the setting up of a Palestinian state. Israel’s forces would leave the West Bank and Gaza according to a phased timetable like the one worked out for the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan. The PLO would agree to a transition period that would give Israel assurances that PLO guerrilla forces would not come into the territory left by the departing Israeli troops.

During the transition, United Nations forces would take over control of the occupied territories while negotiations went on between Israel and Palestinian representatives to determine the borders and security arrangements between Israel and the new Palestinian state. UN troops could remain on the Palestinian side of the border for as long as Israel wanted. Arafat has circulated a plan among European Community foreign ministers by which, during the negotiations, the Palestinians in the occupied territories would vote on whether they preferred independence, confederation with Israel, or confederation with Jordan

To get around Israel’s reluctance to talk to the PLO, the PLO as such would not take part in the negotiations. Instead, representatives would be drawn from a provisional government to be appointed by the PLO, consisting of Palestinians living both inside and outside the occupied territories. Abu Sharif told me that Arafat would be the head of the government with the title of prime minister. The provisional government would be set up as soon as the United Nations organizes a “preparatory committee” to begin consultations toward convening a peace conference. The PLO would not object to being part of a joint Arab delegation that represented all the Arab parties. But it opposes teaming up with Jordan alone, as has been suggested by the United States in the past.

To achieve its objective, the PLO’s strategy—so the leaders I talked to told me—is to keep up pressure on the Israeli government until it is forced to deal with the PLO and accept the inevitability of a Palestinian state. To do this, the PLO has two tactics. One is to make sure that the intifada continues because, without it, the PLO loses its only real leverage. The second is to keep pressing the Palestinian case not only in Europe but especially in the US and in Israel.

Abu Sharif told me he was heartened by what he believed was a clear trend toward public acceptance of the PLO within Israel, as well as growing discontent within the army over the intifada. Abu Sharif pointed to a poll published in the Tel Aviv daily Yedioth Aharonoth on December 23, 1988, that said 54 percent of Israel’s Jewish citizens could support talks with the PLO.3 He also refers to comments suggesting a need to deal with the PLO by Mordechai Gur, a former chief of staff who is now an Israeli cabinet minister. He believes that the intifada and the PLO’s initiative have shaken up Israeli politics, with the result that a new generation of leaders will emerge in the next parliamentary elections. He has been closely involved with the PLO effort to increase contacts not only with American and European Jews but with Israelis as well. He told me about a meeting with Abba Eban during a January symposium in The Hague:4 Eban led the Israeli delegation, which included leftist members of the Knesset, while Abu Sharif headed the one from the PLO. Presumably because Israeli law forbids contacts with the PLO, Abu Sharif said, Eban would not personally greet him or offer to shake hands. Abu Sharif said he then asked somebody to arrange a secret meeting, but Eban apparently declined. “Talks like that are very important because it will help break the barrier of fear on both sides,” Abu Sharif said. He expected Labor and possibly Likud cabinet members eventually to hold secret talks with PLO officials as a way of preparing the way for open discussions.

Some Israelis and other Jews, I pointed out, have not been persuaded that the PLO wanted real peace with Israel. The Likud and Labor parties agreed when forming a new coalition government in December to oppose any dealings with the PLO. I raised the issues that have become persistent concerns: that the Palestinian council has not specifically repealed the National Charter, which calls for one state in Palestine and the destruction of Israel; and that Abu Iyad has been quoted as suggesting that if Palestinians won a state in the West Bank they would use it as a launching pad to devour Israel.

Abu Sharif dismissed both points as nonsense. He contended that the charter was legally superseded by the political program adopted in Algiers, which endorsed United Nations Resolution 181, passed in 1947, a proposal calling for the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states. In addition, the Algiers meeting accepted Resolutions 242 and 338, which implicitly recognize Israel’s right to exist within secure borders. As for Abu Iyad, Abu Sharif said he had reviewed the matter and found that Abu Iyad had never made the statements attributed to him, and that in any event he had voted for the PLO’s initiative.

To pursue these issues further, I asked to meet with the PLO’s foreign minister, Khaddoumi, the most senior PLO official present in Tunis at the time. He is the most pro-Soviet leader in Arafat’s Fatah guerrilla group, and Arafat’s aides were surprised when he readily agreed to see an American journalist. He had a different response about the PLO charter, one I suspect is more representative of the feelings of many senior PLO officials.

“The charter stands as it is,” he told me. When I asked what that meant, he replied: “As long as they are killing my people, I should shout. I should curse them. People are killed, and you are asking about words? Let the people express themselves. This is psychology, see? We will write hundreds of charters, just to tell the world that we are under occupation.”

In the next breath, Khaddoumi repeated his support for the PLO initiative but he acknowledged that he had made his own decision to recognize Israel with great reluctance. “To please the international community,” he replied when I asked him why he did it. “To prove to them that we are willing to have peace, that we are ready to share with the thief our homes, that if the Jews come from Europe and don’t have homes we are willing to accommodate them. It is painful. Because my home in Jaffa is being occupied by an Israeli who came from Poland. I am not happy, I am not.”

Khaddoumi added, “The time has come for us to clarify things. It is our dream to have one state where we all live together. But if the Israelis dislike the idea of this one state, we are ready for a two-state solution. This is less than 100 percent. You know, when Galileo said the earth revolves around the sun he was [arrested]. But after several centuries everybody was praising the man. So, let us say the right thing at the right time. This is the point.”

American diplomats I have spoken with do not seem greatly concerned about the charter or Abu Iyad’s comments. They accept that the PLO has recognized Israel’s right to exist, and the State Department has rejected Israel’s request that the talks with the PLO be broken off. But to judge from my discussions with PLO officials, other matters are more likely to jeopardize the PLO-US dialogue, which the PLO has expected will lead to an official dialogue with the Israeli government. There is a still considerable gap between the two sides on important issues: the shape that a peace settlement should take, the process leading to a final settlement, and the PLO’s use of violence.

Ambassador Robert Pelletreau, the State Department’s designated interlocutor with the PLO, has held one full-scale meeting lasting an hour and forty minutes with the PLO; this has been followed by several brief “informal” sessions with Hakim Belawi, the PLO’s “ambassador” in Tunis. PLO officials seem to like and respect Pelletreau, although one of them told me that he becomes “stone-faced” in their meetings; even when Abu Sharif encountered Pelletreau at a reception at the British embassy, Abu Sharif found himself doing most of the talking.

Pelletreau’s only public statement so far came immediately after his first session with the PLO. He said the US hoped that the dialogue would lead to direct negotiations between the Israeli government and other parties and that Palestinians would have to be involved in all phases of the process. Pelletreau did not say which Palestinians, or how the Palestinian representatives should be chosen. As for the outcome, President Bush during the campaign clearly voiced his opposition to the establishment of an independent Palestinian state.

On the other hand, PLO officials say that as a minimum the US must recognize the PLO and the right of Palestinians to “self-determination,” or independence. As Abu Sharif explained it, PLO expectations from the dialogue remain high. He said the PLO believes that the US government would not have entered into talks with the PLO if it did not expect at some point to formally recognize the group and accept the demand for statehood. The PLO leaders, moreover, want the Bush administration to apply pressure on Israel to move toward a settlement acceptable to the PLO. Khaddoumi said Washington should cut its aid to Israel by at least 50 percent. Abu Sharif agreed with me that this kind of thinking was unrealistic, but he had some thoughts of his own. Referring to Section 502B of the Foreign Assistance Act, he said that the US government could threaten to sever military aid to Israel if it continued using repressive measures against the intifada.

While Abu Sharif suggested the PLO was ready to be flexible on some matters, he and other PLO officials were adamant in their opposition to the kinds of proposals Yitzhak Shamir is expected to make when he visits Washington in April and that the Bush administration has hinted at. They said that the PLO would accept elections in the occupied territories only if Israeli forces withdrew first. Assuming that Israel does not end its twenty-two-year-old occupation before the start of negotiations, they said they would oppose any efforts to have Palestinians represented only by leaders inside the West Bank and Gaza Strip; even if these leaders were pro-PLO people like Faisal Husseini, they said, this could have the effect of splitting the Palestinian community between the Palestinians in the occupied territories and those in the diaspora. Finally, they would refuse any offer of “autonomy” in the occupied territories unless they had a guarantee that autonomy would be followed by full Palestinian independence.

Two months after taking office, the Bush administration has not put forth any specific view on the nature of negotiations or of a final settlement. By choosing instead to concentrate on ways of creating a favorable climate for peace talks, US officials might have been inviting a collision with the PLO on the matter of Palestinian violence. The issue could become a diversion that dooms negotiations before they even get started, particularly if neither Israel nor the United States is able to agree with the PLO’s basic demands.

According to PLO officials, Pelletreau has constantly raised US concerns about continuing terrorism and guerrilla operations across Israel’s northern border in his meetings with them. Before the talks began, he said the United States “wants terrorism to be at the top of the agenda.” One of Arafat’s problems is that he has been under pressure from PLO military commanders to show concrete support for the intifada by launching attacks from Lebanon. Khaddoumi confirmed to me that Arafat’s Fatah group has “cooled off” offensive guerrilla operations for a period “in order to listen to Mr. Bush.” But Arafat cannot control the militant factions based in Damascus; Habash’s group and Nayif Hawatmeh’s Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine and others have refused to abide by Arafat’s order. For the sake of keeping up the dialogue with the PLO, the State Department has shown a willingness to overlook all the attacks launched thus far. But if any PLO group succeeds in crossing Israel’s border and killing a number of civilians, this will undoubtedly put a severe strain on the US-PLO discussions.

The uprising in the occupied territories may cause a more serious disagreement. On March 12, the Bush administration leaked the first details of its emerging Middle East Policy to The New York Times. A State Department official was quoted as saying that the United States would urge the PLO to block anti-Israeli raids from southern Lebanon. But, far more important, the official said the PLO would be asked to halt violent demonstrations in the occupied territories as well as the distribution of inflammatory leaflets. The PLO would, in effect, be asked to stop the intifada, the official said, as a way of showing both its willingness and its ability to make peace; and similar gestures toward establishing mutual trust were asked of the Israeli government.

Nobody I spoke to earlier in Tunis entertained even for a moment the notion that they should try to bring the intifada to a halt. To the contrary, they expressed as emphatically as they could their feeling that the intifada was the PLO’s main way—perhaps its only way—of bringing pressure on Israel to eventually make concessions favorable to the Palestinians and that it was because of it that they had come this far. The existence of the uprising, in fact, is what has given Arafat the political leeway within the PLO to recognize Israel’s right to exist.

I was not surprised, therefore, to find PLO officials quickly denouncing the State Department’s suggestions when I attended a symposium, “The Road to Peace,” at Columbia University on the afternoon of March 12. Speaking before the assembled Palestinians, Israelis, and American Jews, Nabil Sha’ath, one of Arafat’s longest serving political advisers, said: “We shall continue our intifada. It is the only guarantee that peace can be achieved in the future.”

Afterward when I saw Sha’ath privately, he said the PLO would do everything it could to “abort” the US proposal, in part because it was made without any indication from the US that stopping the intifada would lead to Palestinian independence or even PLO representation at an international conference where statehood could be discussed. (After Sha’ath spoke, Baker told a Senate appropriations subcommittee on March 14 that the US “may ultimately conclude” that there cannot be meaningful negotiations without the PLO.) At most, Sha’ath said, the PLO could agree to a one-time “peace day” with no demonstrations or violence in the occupied territories. To show that the PLO wished to contribute to a favorable climate, he said, the organization would be willing to negotiate a truce on the Israeli-Lebanese border and to meet directly with Israeli government officials before a peace conference.

The PLO reaction helps to shed light on the controversy in January surrounding Arafat’s purported threat to kill Bethlehem Mayor Elias Friej for proposing a truce in the intifada. Abu Sharif told me that Israel’s “propaganda machine” had blown the remarks out of context. But Arafat’s comments recorded at a press conference underscored the crucial role the intifada plays in the PLO’s strategy: “Any Palestinian leader who proposes an end to the intifada exposes himself to the bullets of his own people. The PLO will know how to deal with him.”5

PLO officials expressed grave concern to me that they would lose their influence over the local leaders of the intifada if they called for the uprising to stop before making significant concrete progress toward independence in negotiations. They were particularly worried about the growth of the Palestinian fundamentalist movement known as Hamas. Sha’ath told me that Arafat has only a year to produce results before pressure within the PLO starts to build against Arafat’s efforts.

Because of Abu Sharif’s own past association with violence, I asked him many questions on the subject. Within the PFLP, he told me, he never spoke against the hijackings. “It was a violent thing to do, but I did not condemn it,” he said. “I could understand why. They wanted an entry, to capture the attention of the world. It is a cruel way, a violent way, but a way of drawing the attention of the world to what had been neglected for a long time: the suffering of our people.”

As for the PFLP atrocities, Abu Sharif told me they were “something that I lived with until a certain period, 1971. For a certain period of time, violence was inevitable, but not that kind. It was a short period of time, from 1968 to 1971. In 1971, the PFLP central committee took a decision to stop.” After that, he added, “I had a weapon, a decision of the central committee, to express an opinion [against terrorism] which was coinciding with my own.”

When I asked Abu Sharif to explain the PLO’s present policy, he said that the PLO “will do its best to stop any kind of operation carried out against a third party outside the region.” But he said that “acts of resistance” were a right endowed to people living under occupation.

The statement plainly covered the stone throwing of the intifada, but did the PLO consider it an “act of resistance” to attack Israeli troops more violently inside Israel? “Resistance using all means available,” he replied. “When the French, British, and Americans were resisting the Nazis in Europe, that did not only deal with fighting a soldier standing on your neck.” I asked him what else it could include. “I’m giving you an answer in principle,” he said. “If Rabin is shooting my kid, why shouldn’t my other kid shoot him? Give me a logical answer. If Shamir takes a decision and orders officers and soldiers to shoot my kids, why wouldn’t I give an order to my other kid to shoot Shamir?”

Palestinians, the PLO is saying, will not abandon violence until they feel assured of winning their independence.

—March 16, 1989

This Issue

April 13, 1989

-

1

See Cooley’s article in the Christian Science Monitor, September 14, 1970. Cooley is now a London-based correspondent for ABC news. ↩

-

2

By the PLO’s count, 104 nations, mostly in the third world, have extended diplomatic recognition to the independent Palestinian state declared by the Palestinian council in November. ↩

-

3

A second poll published by Yedioth Aharonoth (February 10, 1989) showed the same result. ↩

-

4

Since November, similar meetings have taken place in Prague, Paris, Oxford, and New York. In addition, Arafat met directly with fifteen Israeli news correspondents in Cairo, February 23, 1989. ↩

-

5

This is the remark as broadcast by Monte Carlo radio on January 2, 1989, and published in The Washington Post, January 3, 1989. A State Department translation of the remark from the Arabic published in the January 19 New York Times went this way: “Whoever thinks of stopping the Intifada before it achieves its goals, I will give him ten bullets in the chest.” ↩