One odd feature of our century’s literature is a metamorphosis to childishness. Childhood had been a subject for great literary artists—Wordsworth, Dickens, Tolstoy, Aksakov, Fournier—for almost a hundred years, but they had always created it retrospectively, revealed it from the standpoint of maturity. The war, and Freud, possibly Dada and Surrealism too, seemed to change all that. Childishness began to extrude itself into literature on its own terms, as it were; it crawled out raw and unmodified from the subconscious.

After World War I the new state of Poland seemed a suitable experimental region—“God’s playground” as it had been called, where the ruling classes had never taken power and politics seriously, and with to them fatal results. The grown-ups of Russia, Germany, and Austria had closed the place down. But the Polish intelligentsia had never lost its identity, or, in a sense, its wonderful irresponsibility.

Between the wars was its heyday. Warsaw intellectuals and lively periodicals like Skamander inaugurated new kinds of writing that drew inspiration from other European authors—Proust, Joyce, Kafka, Thomas Mann—but possessed a very definitely Polish personality and Polish characteristics. Witold Gombrowicz, who achieved international fame in 1938 with his novel Ferdydurke, had for some years before been publishing in Warsaw his stories and studies of adolescence. Ignacy Witkiewicz, usually known as Witkacy from the way he signed his paintings, was perhaps the most versatile Polish artist and writer of the time, pioneering and encouraging new cliques and movements. He committed suicide during the German and Russian invasion of 1939, and Gombrowicz had emigrated to Argentina the year before, never returning to Poland.

The two made a trio with a small, shy Jewish writer from the provincial Galician town of Drohobycz (now in the Soviet Union), whom Witkacy championed in 1934 as the most significant contemporary phenomenon in Polish literature. This was Bruno Schulz, whose fantasy The Street of Crocodiles, sometimes translated under the title Cinnamon Shops, had just appeared. Unremarked before Witkacy hailed it as a masterpiece, the gestation of Schulz’s book was itself sufficiently extraordinary. The son of a dry-goods merchant, and himself the drawing master at a local high school, Schulz depended on letters to friends for intellectual support and nourishment. In 1929 a fortunate chance introduced him to Debora Vogel, a girl from Lvov who was a poet and had a Ph.D. in philosophy; she had scored a critical success with a book of imaginative prose called The Acacias Are in Bloom. They began writing letters to each other, and Schulz’s letters developed postscripts, of greater and greater length and originality of fantasy, with a mythology of his childhood, his family, and the town where he lived.

In 1938, when he was well known in writers’ circles, Schulz wrote to the editor of a literary periodical, modestly disclaiming that he had been an influence on Gombrowicz, whose Memoir from Adolescence had, he pointed out, appeared in 1933, The Street of Crocodiles a year later. “What led to the association of our names and respective works were certain fortuitous similarities,” he wrote. When Ferdydurke appeared in 1938 Schulz wrote an enthusiastic review of it in Skamander, reprinted in Letters and Drawings of Bruno Schulz. He observes that “until now a man looked at himself…from the official side of things,” and that what happened inside him led “an orphaned life outside…reality,” “a doleful life of unaccepted and unrecorded meaning.” It was this inner childishness that he and Gombrowicz sought, in their separate ways, to mythologize. “Gombrowicz,” Schulz wrote,

showed that the mature and clear forms of our spiritual existence…live in us more as eternally strained intention than as reality. As reality we live permanently below this plateau in a completely honorless and inglorious domain that is so flimsy that we also hesitate to grant it even the semblance of existence.

(“Flimsy” is a key word here.) Ferdydurke, in which the middle-aged narrator hero has been transformed into a schoolboy, “breaks through the barrier of seriousness with unheard-of audacity.”

Schulz himself did not use such comparatively direct methods. His child’s-eye vision is utterly natural, perpetuating into middle age the humble, celestial rubbish that filled our consciousness in infancy, and helped to pass its time. There is no sense of looking back; “not a touch of whimsy in it,” as V.S. Pritchett, a devotee of Schulz, has commented. Since Schulz’s time childishness has been both stereotyped and made use of—we can all fondly play catcher in the rye—and Gombrowicz, who struggled heroically to free himself from the coils of theory and literary fashion, eventually succumbed to being typecast as one of the early “mad” writers.

It is impossible to typecast Schulz because, to quote Pritchett again, “his sense of life is a conspiracy of improvised myths.” Again, the word “improvised” is crucial. As his postscripts grew and flew off to his correspondent, Schulz’s imagination dissolved, reformed, liquidated itself. His wonderful language—a kind of sparkling liquid Polishness, as an admirer has said—is almost impossible to translate into a less vivacious and ebullient medium. Even Goncharov’s fantasies of the Russian village of Oblomovka, or Proust’s magical first sentences in A la recherche du temps perdu, seem set in monumental majesty—very unchildish—compared to the eddies and spiraling paragraphs of “Cinammon Shops” and “Crocodile Street,” two of the chapters, sections, or stories in Schulz’s book, which was followed a year later by a similar compilation called Sanitorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass.

Advertisement

In these stories, the father figure, then hero, almost becomes a bird or a cockroach, as he acts out internal fascinations not normally on adult display. Adela, the housemaid, has only to wag her finger at him—the sign of tickling—for him “to rush through all the rooms in a wild panic, banging the doors after him, to fall at last flat on the bed in the farthest room and wriggle in convulsions of laughter.” Perched on the pelmet he becomes an enormous bird, a sad stuffed condor; once, as an enormous cockroach, he is almost served up in crayfish sauce at family dinner. He breeds strange birds in the attic, which fly away and return a few chapters later in outlandishly spiky forms, flying on their backs, or blind, or with misshapen beaks like padlocks, or “covered with curiously colored lumps.” Debora Vogel, the recipient of these amazing reveries (which do not in the least seem like fantasy) has herself a surname that in German means “bird.” Perhaps his postscripts were Schulz’s strange way of making love to her—strange and, at the same time, delicate, unimportunate, unpretentious.

In one of his letters Schulz refers to a door, the good solid old door in the kitchen of his childhood. “On one side lies life and its restricted freedom, on the other—art. That door leads from the captivity of Bruno, a timid teacher of arts and crafts, to the freedom of Joseph, the hero of The Street of Crocodiles.” In an introduction to the book the Polish poet Jerzy Ficowski, who has helped to do for Schulz what Max Brod did for Kafka, comments that “behind the mythological faith of the writer there peers, again and again, the mocking grin of reality, revealing the ephemeral nature of the fictions that seek to contend with it.” That seems to me misleading. There is no Peter Pan element in Schulz’s imagination; rather does he show, with a tender excitement far removed from the calculated shamelessness of Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke, that we really and always do live in two worlds, and that the ability to live in and with both is a sign of sanity. Not many of us can turn the compulsive contingencies of the inner life into art, but when it has been done—and in so magical a form as this—we recognize its truth from our own inner experience.

No whimsy there, and nothing coy either. Schulz as a writer was a grown man, whose sexuality is immanent in the marvelous agitations of his world: in Adela’s silken legs, the motion of her finger as she threatens to tickle the father, and in an idiot girl’s frenzied rubbing of herself on an elder tree by the town rubbish dump. In his drawings reproduced in the book under review, particularly the ones from a collection called “I dolatry,” two-dimensional sex takes over, its fixed poses replacing the dynamic three-dimensional fantasy of “Crocodile Street” and “Cinnamon Shops.” In a sense we are now in the night life of Weimar Berlin—and indeed a Gestapo officer is said to have admired Schulz’s drawings—but even so there is a fluidity, a childishness, an innocence in these beautiful fetishistic little sketches that wholly removes them from the pornographic fixity in the pictorial world of—say—Balthus. There is rather a touch of Fragonard, more than a touch of Picasso, in the slender nudes with their big heads and bobbed hair, who stretch out an alluring toe toward their groveling male devotees, whose nakedness has the pathos of desire but also its dignity. There is a singualr naturalness and unselfconsciousness in Schulz’s graphic world, in which he often features himself, surrounded at times by the higgledy-piggledy intimacy of a big patriarchal Jewish household. For his engraving he used the laborious cliché-verre technique, drawing on gelatin-coated glass and developing the print like a photographic negative. It produced for him lines and shadings of great delicacy, effects entirely his own.

Schulz admired and translated The Trial, but his world does not in the least resemble Kafka’s. There is no quest, no terrible unknown compulsions, no anguish before the law. Schulz’s family, with whom he was in his own peculiar way on good terms, had no Yiddish or Hebrew but spoke German and Polish. In Polish he was as at home as Celan, another exile and victim, was to be in German, or as Italo Svevo, otherwise Ettore Schmitz, was in Italian. And like Mandelstam, Schulz acknowledged no particular Jewish identity; he was just different from everybody. Gombrowicz, who came from a Polish gentry family in Samogitia, the heart of old Lithuania, was much more aware of his background than Schulz was, and always felt divided between his own “schoolboy” personality and his semiaristocratic provenance. In an open letter to Schulz commissioned by the editor of Studio, beginning “My Good Bruno,” Gombrowicz cannot help patronizing his friend, even while praising him, and rudely dwelling on the fact that he has not actually read The Street of Crocodiles, even though he is sure he admires it. (In his diary he comments more candidly that Schulz’s stories “bored him stiff.”* ) Schulz’s letter for Studio in reply is a model of rational selfexplanation, ignoring the innuendo of class and race that Gombrowicz—perhaps deliberately, perhaps not—had let emerge in his own letter, and that seems to reflect the jealousy of the conscious and determined intellectual for the natural and involuntary fantasist who had crawled out as if from the woodwork.

Advertisement

“Dance with an ordinary woman” was one of Gombrowicz’s more bracing prescriptions. Schulz indeed had done so, and become engaged to her: a Catholic girl called Józefina Szelinska for whom he felt a naive warmth and affection, which was evidently returned. But somehow it all petered out, and his many letters to his one-time fiancée have disappeared, whereas Kafka’s to his Milena have survived. Even in the matter of marriage, though, the pair of writers were probably very different. Schulz was timid, poor, and constitutionally reluctant to leave the place he worked and dreamed in, the burrow of Drohobycz, no matter how much he might have seemed to want to.

In his letters to Romana Halpern, a handsome, clever, and sympathetic woman who worked as a journalist and was to be killed by the Germans in Warsaw just before its liberation, he confided his plans for change, wider recognition, a job in Warsaw. She helped him; in 1938 he even spent three weeks in Paris. But the war found him still back home, and in 1942, after a temporary respite during which Galicia became part of the USSR, the Germans reoccupied the area and started to carry out their Final Solution. Cornered on the street one day during a “drive” Schulz was shot in the head by a Gestapo man named Günther, who no doubt felt—if he felt anything—that he was casually stamping on a cockroach. Friends had already prepared non-Jewish papers for Schulz, and had plans to help him disappear into the Polish countryside, but he had been characteristically reluctant to take the step.

Illustrating his own books Schulz felt himself to be akin to a medieval priest or craftsman. And like a good child he dreamed and scribbled and drew, secretly and spontaneously. From his letters to Romana Halpern it is clear that his sudden literary fame depressed and disturbed him. He consulted her anxiously about his plans for marriage, which she hinted might be bad for his writing and make him “middle-class.” He refutes this, defending his fiancée warmly; but Romana, herself a divorcée, probably had a clearer idea than Schulz himself did of what might go wrong. By the late Thirties he is very low, unable to write, planning masterpieces commensurate with his new reputation; but obscurely longing, one senses, to return to that womblike existence in which his real books had gestated, and in which he had drawn his haunting little pictures of bearded rabbis at their sabbath meal, or slim-legged blondes gazing impassively at their prostrate suitors.

Gombrowicz understood Schulz’s plight. “He approached art like a lake, with the intention of drowning in it.” His masochism made it impossible for him to impose himself on a project, or to plan a work ahead. Cinnamon Shops and its successor, Sanitorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass, remained his only achievements, although he meditated on blending them in some way into a long work to be called Messiah, perhaps inspired by his deep admiration for Thomas Mann’s encyclopedic novel Joseph and His Brothers. Nothing of this survives, if it ever existed. Yet on the strength of his two little books Schulz is undoubtedly one of the masters of our century’s imaginative fiction. He himself probably wrote the anonymous blurb for Sanatorium, in which he spoke of fiction’s “dream of a renewal of life through the power of delight.” That is an accurate description of the way his books work on us.

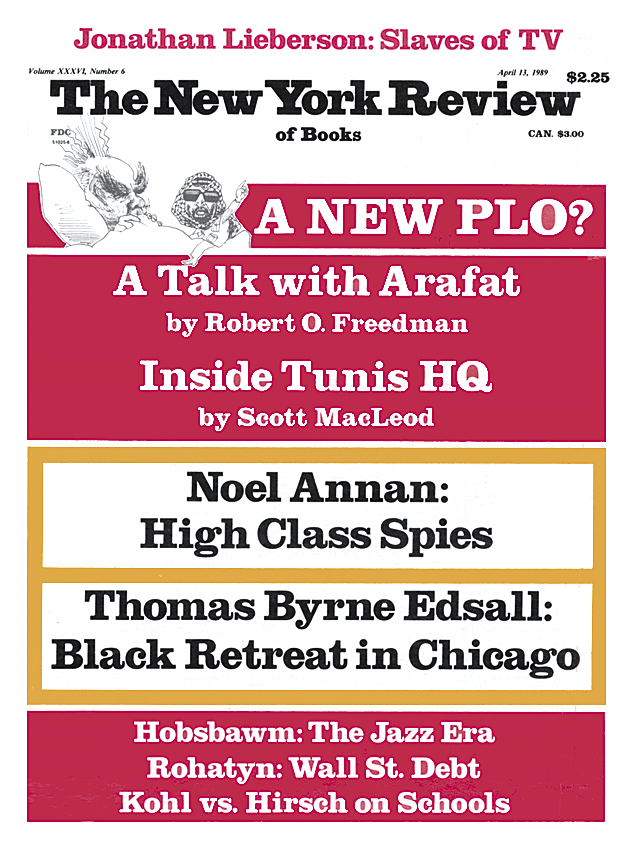

This Issue

April 13, 1989

-

*

The section on Schulz is published opposite. ↩