In response to:

The Poet in Limbo from the December 22, 1988 issue

To the Editors:

I would like to comment on Professor Donoghue’s fireside chat about my tastefully designed, handsomely jacketed Conrad Aiken: Poet of White Horse Vale, University of Georgia Press, $34.95, illustrated [NYR, December 22, 1988].

There is much to praise in his critique, especially its length. Poor Aiken! Professor Donoghue’s level-headed sermon makes clear that his main sin lay in choosing to become Conrad Aiken. A further blot, aside from heeding Freud and Jung, was the method he selected for “not being modern,” abjuring the “better” ways “suggested by the work of A.E. Housman, Frost, E.A. Robinson, Wilfred Owen, and Edward Thomas,” although it probably mattered little in the long run since he, like Kafka, had nothing to write about except himself, “a central concern of Romanticism.”

What Professor Donoghue, an Enlightenment philosophe at heart, apparently cannot countenance is the fact that literature, unlike his review, remains an emotional enterprise, an act of passion, however over-determined or overtly rational its modalities. It was Eliot who preached the importance of poets seeking “whatever subject matter allows us the most powerful and the most secret release.”1 Which helps explain why Professor Donoghue’s not unsympathetic New Critical reading of my book and Aiken’s poetic evolution rendered a disservice to both.

Richard Ellmann predicted that literary biographies would “continue to be archival, but the best ones will offer speculations, conjectures, hypotheses.”2 In other words, under the pressure of increasing knowledge, they will have to take more chances, echoing modernist tactics in that sense, with a similar threat of lost audiences. For me, this meant reliance on a well-established body of psychoanalytic insights that obviously caused Professor Donoghue some uneasiness, an uneasiness I share to a certain degree, at least anent the potential for sacrificing experience to theory.

The result was a critical biography that strives, for instance, to demonstrate how Aiken could achieve the mastery evident throughout Preludes for Memnon without resolving the neurotic compulsions stunting his growth as a human being. I will not attempt here to defend the validity of my conclusions, but it is crucial to the understanding of any artist’s maturation drama that the complicated process behind aesthetic decision-making not be reduced to a set of luxury car options.

Aiken, who always wrote too much verse too readily and had a terrible struggle to elude the noose of friend Eliot’s contempt and precocious accomplishments, retarded his own poetic development by aping the successes of admired contemporaries, including Eliot, John Masefield, John Gould Fletcher, and Edgar Lee Masters. Why he did so relates to the profound insecurity—fears of an absent self—trembling beneath his flippant, skeptical, often pugnacious surface. And, yes, the insecurity and a concomitant misogyny, reinforced by a host of cultural and educational factors, can be traced back to childhood abuse and the loss of both parents at puberty’s threshold.

Consequently, when he located, at last, the voice and content that would permit him to produce the major poetry he was capable of producing, it was a convoluted psychological and literary event. Whitman and Tennyson, not Stevens, supplied pivotal models, though Professor Donoghue is right to stress the latter’s continuing impact. The symbolic lyric sequence, a series of reflexive allegories, marking Aiken’s emergence as a powerful American modernist came in the spring of 1924, while he was in the grip of a serious depression. It is a measure of Professor Donoghue’s antipathy toward depth psychology that he wastes space poking fun at my anlaysis of “Changing Mind” (1925), which I had conceded was “more fun to interpret than to read or experience,” but completely ignores this extraordinary group of poems.

As for the historic and noetic circumstances abetting Aiken’s artistic progress (or lack of same), their complexity resists a brief summary. It might be noted in passing, however, that Nietzsche’s effort to shift Western philosophy’s focus from inferential reasoning to impressionistic existentialism, from logic to psychology, complemented his faith in psychoanalytic paradigms. Freud and Nietzsche were undeniable American obsessions in the early decades of this century, and Aiken’s tenacious Romantic introspection reflected a 1920’s intellectual climate.

Until that “drastically edited” Selected Poems slouches round from Bethlehem to break Aiken out of his solipsistic limbo, I will hunker in the nearest tavern to nurse a few beers and my “grudge” against the English language. Perhaps, in time, after scanning Ushant, A Reviewer’s ABC, The Collected Short Stories, and as much of The Collective Poems’ “meditative copiousness” as they can tolerate, friends and relatives will forgive me for having perpetrated Conrad Aiken: Poet of White Horse Vale, University of Georgia Press, $34.95, illustrated, on a public clamoring for another biography of Ezra Pound.

Edward Butscher

Briarwood, New York

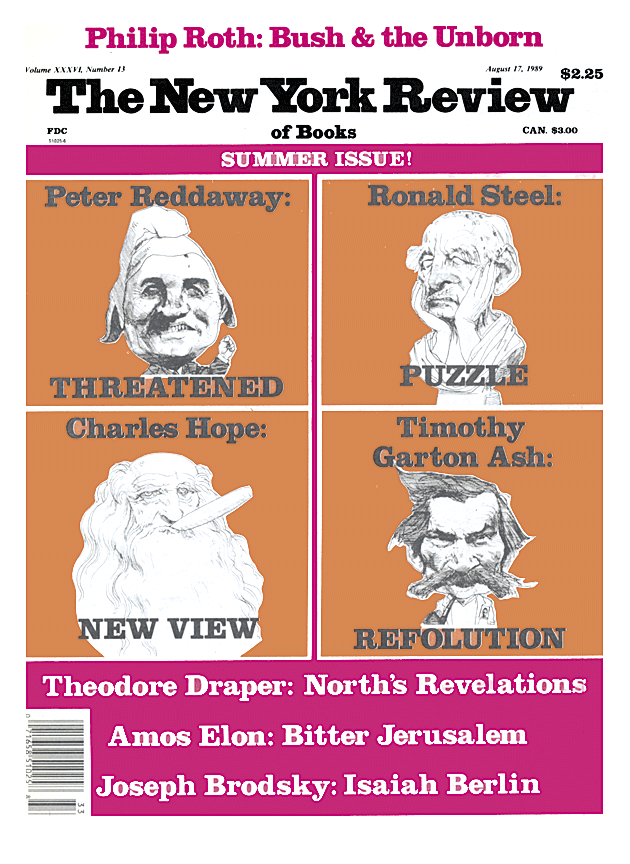

This Issue

August 17, 1989