Paul Auster’s Moon Palace tells the old story—of an alienated youth struggling to understand how he may belong in a difficult time and place—with an intelligent sympathy that renews its pertinence. Marco Stanley Fogg, Auster’s narrator-hero, is an orphan, a condition whose possibilities for fiction Marco himself fully appreciates. He has never known who his father was, his mother died when he was eleven, and his Uncle Victor, a musician who took care of him after that, died when Marco was an undergraduate at Columbia in the late 1960s. As his name trebly asserts, Marco is also a born traveler, someone who has to find his place in the world rather than inherit it. His fate, he bravely says as his story begins, at first seemed simply to be to “live dangerously,” to plunge into a future that his past could not predict. But it is the past that is written largest in his account of his life between 1969 and 1972, a time that almost killed him.

Left by his uncle’s death with barely enough money to finish college, he disdains to ask for scholarships or loans or work, just makes it to graduation, and then becomes one of the homeless, sleeping in parks or cheap movie houses, finding food in garbage cans, relying on occasional handouts from pitying strangers. His idea is to stop “living through words,” themselves a form of inheritance, and to abandon himself to “the chaos of the world” in the hope of learning its “secret harmony.” These aspirations are not very surprising in a young intellectual like Marco, and faint strains of “secret harmony” may be audible when, after he is rejected on psychiatric grounds from the draft, he is rescued from illness and starvation by two loyal and loving friends.

Recuperating, he finds a job as companion and reader to Thomas Effing, a crippled, blind, and very eccentric octogenarian. Effing is a fantasist on a grand scale, boasting, for example, that his telekinetic powers caused the New York blackout of 1965. But his account of his past fascinates and gradually convinces Marco. Effing claims that he was, long ago, a rich avant-garde artist named Julian Barber, who, after marrying a frigid society girl and fathering a son, ran off to the West in 1916 to become an American painter. Stranded and starving in the wilds of southern Utah, he found a cave stocked with food, killed the outlaw Gresham brothers, whose hideout it was, and appropriated their loot, learned to paint in a way he could respect, and eventually reached San Francisco where (thanks to Gresham’s law?) he made another fortune by investing his doubly stolen money.

Fear of exposure then drove this model capitalist to cover in Chinatown, where he squandered some of the money on drugs, gambling, and women, and was crippled for life by a mugger. In 1920 he sailed to Paris, stayed there until war came in 1939, and then returned to New York, never revealing himself to anyone who had known him as Julian Barber.

Marco finds this traveler’s tale too farfetched to be mere fiction, and its resemblances to his own life seem irresistible. He too nearly starved to death in solitude; he too once, in Central Park, lived in a cave; he too renounced a bad life and stumbled onto another, perhaps freer, one; he too, after Effing’s death, would live in Chinatown with his lover, Kitty Wu. Such harmonies are amplified by other hints of “synchronicity” in his experience, many of them involving the moon. As a student at Columbia he could see from his west side apartment the sign on a Chinese restaurant, the Moon Palace; his uncle died in Idaho, in 1967, after touring with a band called the Moon Men. Marco is a close student of the imaginary lunar voyages of Lucian, Francis Godwin, Cyrano de Bergerac, Jules Verne, and other earlier fantasists. He is fascinated by a painting of the American West before the white men took it over, Ralph Blakelock’s Moonlight, which Effing sends him to look at in the Brooklyn Museum; the rising of the moon over the coastal hills of Southern California is, at the book’s end, what seems to encourage his hope that here, at last, “is where my life begins.”

The danger, of course, is lunacy. Though he tries to live without words. Marco’s life is, like anyone’s, made up of his and other people’s stories, whose coherent terms can’t be trusted to represent some coherence “beyond” language. Even Marco, who resolutely makes connections, learns to be cautious about supposing that he’s living out a coherent fiction, and Auster has his own reservations. Kitty Wu’s nickname for Marco, M.S., has admonitory force, and Auster loads the book with names that evoke anxiety about the status of what we know. Effing had traveled to France on the S.S. Descartes; his New York housekeeper is Mrs. Hume (née Bacon); Solomon Barber, the son Effing abandoned, has written a book on Bishop Berkeley’s sojourn in America. But philosophical doubt about speculative instruments can’t quite spoil the excitement of what they show us—in another of Solomon Barber’s books Marco learns that Thomas Harriot, the Elizabethan scientist and magus, was the first person to look at the moon through a telescope, and Solomon’s juvenile novel about his search for his lost father changes the family name to Kepler.

Advertisement

To trump up profundity by planting appropriate philosophical clues is easy enough, but Auster’s game has more in mind. The examined life, as Marco tries to live it, is strikingly similar to writing fiction; and Auster’s insistent manipulation of patterns and coincidences reduces the gap between the author’s skeptical omniscience and the characters’ struggles with the words and stories out of which they must contrive some kind of life. Solomon, whom Marco befriends after Effing’s death, is a sad example of what words can do to life. Bald, immensely fat, unmarried and unloved, Solomon is a historian whose teaching jobs have never matched the distinction of his scholarly work. As a teen-ager he tried to express his sense of life in a lurid novel about a boy who searches the West for a vanished father, kills him, and later accidentally kills his own son. To father may also be to destroy, as Marco himself learns when Kitty insists on aborting the child they have conceived; and he, near despair, breaks with her and agrees to go west with Solomon, to search for the cave where Julian Barber was reborn as Thomas Effing. But when they stop at the cemetery in Chicago where Marco’s mother, once a student of Solomon’s, is buried, Solomon, as if emerging from a pop gothic novel, lets slip the fact that he himself is Marco’s father and then, shrinking from Marco’s wrath, falls into a newly dug grave and is fatally injured. Marco goes on to Utah alone, finds that the site of the cave now lies deep beneath Lake Powell, and, after his car is stolen, continues on foot to the coast, “the end of the world” where he hopes his life, like his grandfather’s, may finally begin.

Marco has a bookish sense of reality, to say the least, and his reading, or overreading, of it is Auster’s subject. In carrying his literary clue-hunting to ludicrous extremes, Marco exemplifies how we derive what we know from language, as well as how hard it is not to suspect—and hope—that language interferes with more immediate ways of knowing. “I understood,” he says early in his story.

that I had already spent too much of my life living through words, and if this time was going to have any meaning for me, I would have to live in it as fully as possible, shunning everything but the here and now, the tangible, the vast sensorium pressing down on my skin.

It seems a very innocent, very American resolve; what can the “it” we live in be if not language itself, the words and stories that are our here and now?

Language of course tends to repeat itself, as it does when Marco discovers that the words he once found in a fortune cookie at the Moon Palace—“The sun is the past, the earth is the present, the moon is the future”—were written in 1919 by the great Nikola Tesla, whose tragically failed career was closely connected to the ambiguous success of Thomas Effing, his old acquaintance. Even Marco can’t tell what this coincidence might mean; meaning, Auster appreciates, is something we add to life at our peril. But he also appreciates how hard it is to avoid meaning, and how much more perilous it would be to settle for a merely nominal reality without at least wanting more. The Marco Fogg who tells his own story knows more than he did while living it, but he doesn’t know everything; and it’s one of the virtues of his fine novel that Paul Auster can explore Marco’s unknowing so ingeniously and fondly without ever sounding as if he himself knows everything that his character does not.

Dennis Cooper’s Closer shows young lives not beginning but on the verge of ending in California, here conceived as “the end of the world” in a sense that Moon Palace doesn’t suggest. Cooper, whose purposes are anything but “regional,” doesn’t call it California, but the big roads are “freeways,” and one of the characters has clearly spent more time at Disneyland than anyone probably should. The center of the action is a high school in a well-to-do suburb; all the main characters are homosexual; the time seems to be around 1980, since a teen-ager is reported remembering that The Doors were a popular group when he was “a little boy,” and AIDS seems unheard of.

Advertisement

Closer is a kind of homosexual La Ronde, following the interconnected couplings of six high-school boys and an older pederast. The novel seems meant to be, as it indeed is, shocking, at least for most readers, abundantly clinical in erotic details and unsparing in its portrayal of the depressing tone of a subculture. At sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, Cooper’s youngsters are coolly and ruthlessly committed to fulfilling their desires, to which their ambiance offers unexpectedly little resistance. The few straight schoolmates who appear seem wholly tolerant and understanding of their friends’ deviance; parents are determined to know as little as possible about their sons’ private lives; the only teacher to make an appearance in the book is not just a fool but a drug user who is in the closet; explicit homosexual and sado-masochistic magazines and splatter and snuff movies are as readily accessible to the young men as People magazine or Star Wars; minors have no difficulty finding and being admitted to gay bars; and of course soft and hard drugs are everywhere. None of this may be surprising, bit by bit, but the bits are added up into a kind of sensual utopia where effort or regret is quite unknown, and I imagine that while some readers will be outraged by the book, some others will enjoy it as pornography.

This would be too bad, since Cooper’s intentions appear to be more interesting and honorable. Closer, I think, is intended to be a story about the imagination under the direst kind of pressure, about how desire can persist to the brink of self-destruction and beyond. Certainly all these sad young men have some creative interests. John draws, David fantasizes that he’s a rock star, George, who keeps LSD in a Mickey Mouse hat and wishes he lived in Disneyland, describes his perplexities in a diary, Cliff is a photographer and Alex a would-be film-maker, and Steve, more a managerial type, contrives an elaborate disco in his parents’ four-car garage. None of them may have serious talent, but their dreams of creativity, like their devotion to sex and drugs and general nonconformity, seem to reach toward some better life that indifferent families, “youth culture,” or the predatory world of adult pedophilia can’t give them.

But beyond the unpleasantness of their surroundings waits something even worse. “I’m only sincere when I forget who I am,” the nearly insane David reflects, and his illusion that he’s a “gorgeous” rock idol embodies a despair about the self that the others feel only somewhat less extremely. “Everything but good looks should be pointless,” thinks Alex, the film student, and their obsession with being physically attractive, or possessing others who are, moves the book in two directions at once.

One direction, an obvious one, is toward comment on the general culture, where the dream of perfection in the body afflicts not only young people of every sexual persuasion, whose uncertainty about their ability and worth at least gives them some excuse, but also a remarkable number of their elders, who really ought to know better. The other is toward a psychic pathology in which death is the mother of beauty in a sense Wallace Stevens may not have meant. The book’s main adult figure, Philippe, once joined a club of men who “wanted to kill someone cute during sex,” and both Philippe the alcoholic coprophiliac and his alarming friend Tom, who’s bent on mutilating and killing his partners while observing the punctilio that they must consent, clearly associate desire with the destruction of its object. The body, the seat of “cuteness,” is also the seat of primal self-disgust, and such a sexuality, as Sade told us, aims at transcending not only the sexual act but everything else as well. But then, in a world where all is possible and no conceivable sensation goes unfelt, literal death may be no more than a closing formality anyway. “Kill me, I can’t feel anything,” one of the characters begs, and the logic of his request has been made clear.

Closer is a noncommittal, rigorously descriptive, unmoralizing book, painful or even emetic in effect. But it seems an attempt to face squarely what Cooper sees as the implications of homosexuality’s darkest corners. If this is so, it is a work of considerable courage.

While the jacket of Barry Hannah’s Boomerang calls it a “tender weaving of novel and autobiography,” the copyright page says, “This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.” What it means to “use fictitiously” Oxford, Mississippi, or a narrator called Barry Hannah who is a writer-in-residence at the university there, is a little unclear to me, but fictionalized or free-form autobiography has been around long enough, I guess, to cause little difficulty.

The book mixes loose personal reminiscence—gathered, as if in a writer’s notebook, under headings like “Oxford,” “Uncles,” “Lost Pilots,””Dogs,” and the like—with a fragmentary story that sounds invented, and seems promising. The reminiscences concern Barry (the narrator) in childhood and youth, when he was “tiny,” liked sports and war games, and played the trumpet, and Barry grown up, when (at 5′ 9″) he still feels tiny, thinks a lot about war, and plays the trumpet now and then. We hear something about his three difficult marriages, about drink and drugs and motorcycles and fishing, about his older relatives, about celebrities he has met in Hollywood and Aspen and elsewhere, about the public people and actions that give him a pain.

Much of this is charming moment by moment, as told in the brash, what-the-hell voice that is Hannah’s chief gift, but it doesn’t lend itself to variety or surprise. Barry isn’t alone, after all, in disliking Arab oil producers, feminism, the Pope, Jimmy Swaggart, “long-winded phony bastards” like Plato, high-school football coaches, lawyers, “rich phony celebrities” who put on pop concerts for famine victims, or Czech tennis players of all genders. Nor is it surprising that he loves his parents and his children, his old friends and teachers, animals, and the South; but when he starts mentioning people he approves of in the arts, he mostly seems to be sending them valentines—to Robert Altman (“kind and brilliant”), Willie Morris (“an enormous heart made of pure gold”), Jack Nicholson and Michael Douglas (“both delightful and civil people”), Norman Mailer and Alex Haley (“right fellows”), Seymour Lawrence (“a golden man”), Thomas McGuane (“a champion at everything”), and more. He tries to draw conclusions but they tend to become blurred, as when, after reporting a local tragedy in which a stoned Rambo fan has randomly shot and killed a four-year-old sitting in a car, he writes:

I was reading Hunter Thompson’s new book, Generation of Swine. There was some old Jeep in a pasture with plastic explosives in it. Hunter is a mature fifty, I think. Yet grown men were shooting at the Jeep to see it explode. Things get slow. Rick Kelley and I went out and shot four snakes in Jerry Hoar’s pond the other midday because things were slow. We were letting off the twenty gauge at all squirming things. But nobody thought about blasting into a car with a family in it. This killing was so random and heinous it made Oxford cry. Where do these people come from?

I suppose that Barry is trying not to think that some of them might come, by devious, mysterious routes, from places where people shoot guns at anything when things get slow.

Barry, at forty-six, sounds like someone at least for the moment disaffected with his life and career; things do get slow sometimes, and a little self-pity never hurt anyone. But his complaints—that he’s “so tiny compared to all the real men,” that “the old guys are me now, is the horror,” that “the calamity is that we get only seventy-five years to know everything and that we knew more by our guts when we were young than we do with all these books and years and children behind us”—also seem to be more than merely personal. They are ways of setting the stage for the best thing in the book, a character who’s not a victim of life at all. This is Barton Benton Yelverston, first imagined by Barry as a kind of beau ideal of an uncle and then, little by little, given reality as someone whom he meets and greatly admires. Yelverston’s name sounds invented, and presumably he is what makes this autobiographical book also a novel.

Yelverston is older, taller (6′ 3″), good at sports, good with women, good at making money (apparently in war-related enterprises); and the suspicion that he is a nobler, more capable anti-self for Barry is at times encouraged, as in their separate memories of being hit in the teeth by ricochets from their own BB guns. Yelverston got rich young, has read some books and done some drinking but no more of either than he can handle, moves in serious political and cultural circles; his own marriage failed after fifteen years, but it hasn’t fazed him much. What does get to him is the murder of his son and daughter-in-law by black drug pirates, while boating on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway.

Being both a devoted father and a man of honor, Yelverston vows revenge and gets it, when he and his ex-wife, brought back together by the tragedy, “joined with the sheriffs along the river and brought the crew to justice.” Like other details of Yelverston’s story, this one seems to call for elaboration, but results, not details, are what matter to Barry about Yelverston. The main thing is that the gang is caught, imprisoned, and sentenced to death. Yelverston remarries his wife, and they have another son. And, in the story’s most intriguing stroke, Yelverston decides not to let the law take its course and kill the murderers but to “get them out of jail and own them,” which in effect he does, making two of them his chauffeurs and their white leader a kind of family friend and business associate. What this says, for instance, about Barry’s view of the institution of slavery isn’t clear, but as a fictional idea it has wonderful possibilities.

I found myself wishing that Hannah could have liberated Yelverston from Barry’s need for such a character and made a more freely developed novel out of him. As it stands, Yelverston seems to be a consoling alter ego for poor Barry, and perhaps a rebuke to his often intimated fears about time and death. The book doesn’t work as either autobiography or fiction, I’d say, but its best ideas and effects encourage a hope that Hannah has better novels in him.

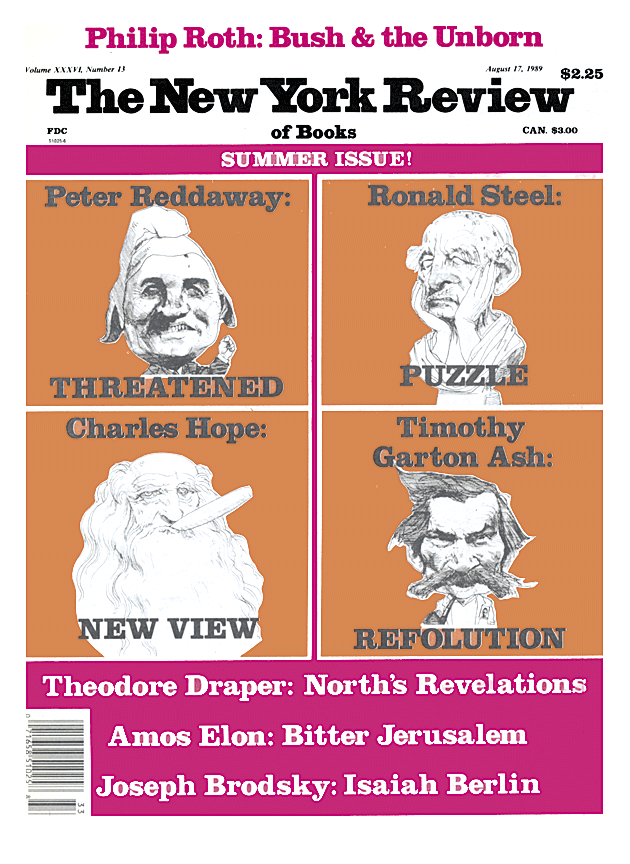

This Issue

August 17, 1989