In response to:

The War on Cocaine from the December 22, 1988 issue

To the Editors:

I read with interest—and alarm—Michael Massings’s article “The War on Cocaine” [NYR, December 22, 1988]. While Mr. Massing obviously went to some lengths to research and describe the scope of the cocaine problem and the effects that cocaine has on Latin American societies, he presents the same tired cliches that armchair critics have put forth over the years as solutions to America’s drug problem. He is also unaware that some of the “facts” that he reports in his article are simply repetitions of misunderstandings that he picked up along the way. Permit me to set the record straight as far as the Department of State’s role in narcotics control is concerned.

Mr. Massing states that “The bureau [of international Narcotics Matters] operates an Inter-regional narcotics Eradication Air Wing, which maintains more than 150 aircraft…. The planes are already active throughout the Andes, spraying marijuana fields, conducting manual eradication, and carrying out assaults on labs and airstrips.” The author goes on to say that the Department is “eager to expand its fleet” and characterizes the airwing as “the Reagan Administration’s twisted approach to the drug problem.” What Mr. Massing’s research did not turn up are the facts: the Democratic Congress, through the 1986 Omnibus Drug Bill, forbade the U.S. Government from titling aircraft to foreign countries, ensuring that the State Department must purchase, operate and maintain all aircraft used in Latin America. Having saddled the Department with an airwing, Congress now refuses to appropriate sufficient funds to allow us to meet airlift requirements or operating and maintenance expenses. The Department has title to 38 aircraft; not nearly enough.

Part of Massing’s proposed solution is the dissolution of the airwing. Mr. Massing is missing a critical point: Latin American governments cannot eradicate or interdict drugs without air assets from the US. Before Operation Blast Furnace took place in Bolivia in 1986, only three helicopters were available in the entire country. Peru faces a similar shortage of equipment and capability. Are we to turn our backs on countries willing to act against narcotics?

We agree that a large part of the solution to our narcotics problem must focus on reducing the demand for drugs; yet I do not believe it is the sole solution. We need to assist other countries, through eradication, interdiction, and additional development assistance, to destroy narcotics at their source and provide alternative opportunities to peasants involved in the narcotics trade.

The Department of State well understands the pricetag for such an approach. In our International Narcotics control Strategy Report (INCSR) for 1988, we stated that economic incentives for Latin American countries struggling against cocaine need to be considered, and we estimated that such incentives could equate to between $200 and $300 million. Congress did not even consider such an approach in last year’s Omnibus Drug Bill, appropriating no additional funding for overseas drug control programs.

In conclusion, what Mr. Massing’s article fails to point out is the fact that the US financial contribution to the international war on drugs is paltry in comparison to the vast profits generated by the drug trade. Our entire international budget (slightly over $200 million) is equivalent to the value of a few decent seizures. Money alone is not the answer; all the money in the world will not solve the drug problem if political will is absent. But we need to look at our own political will, too, as we seek solutions to a problem which threatens the US, indeed the world.

Ann B. Wrobleski

Assistant Secretary

International Narcotics Matters

US Department of State

Washington, DC

Michael Massing replies:

From Ann Wrobleski’s letter, I can’t tell if she’s more angry at me or Congress. One way or another, I have some problems deciphering her message. After first asserting that the amount of money we are spending in the source countries is inadequate, she proceeds to maintain that money isn’t the problem at all—“political’ will” is. This latter is one of the great buzzwords in the drug debate. It is used mostly by administration officials and congressmen who want countries like Colombia to hop to it and do our bidding. Never mind that the drug problem is largely one of our own making; that tens of thousands of indigent people depend on the trade for their livelihood; that fighting the traffickers has already cost the lives of hundreds of judges, politicians, journalists, policemen, and soldiers. Needless to say, while expecting the Colombians to risk their lives in this fight, we don’t give them a cent of economic assistance.

Ms. Wrobleski’s letter bespeaks a classic American attitude: if our current strategy is not working, it must be because we’re not spending enough on it. That the strategy itself might be flawed is simply never considered. To anyone who travels to the Andean countries and avoids the comfortable embassy-and-government circuit, it is immediately apparent that the current mix of eradication and interdiction is doomed to failure. Every year the United States consumes an estimated seventy tons of cocaine; South America produces at least five times that amount. With so much of the substance in the pipeline, no policy based on uprooting coca plants and destroying cocaine labs can have any real impact.

Advertisement

Ms. Wrobleski asserts that the blame for the State Department’s air wing rests with Congress, which forbade the US government from titling aircraft to foreign countries. The real question, though, is not who owns title to the planes, but why the Reagan administration invested so heavily in them in the first place. Anyone who thinks that we are going to make progress in the drug war by sending airplanes to South America has no real understanding of the roots of the problem.

Ms. Wrobleski disputes my figure on the number of aircraft in the State Department’s air wing. I took it from the current International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, issued by her own bureau. It states (on page 19) that the bureau “presently supports operations and maintenance for over 150 aircraft in four major country programs….”

To the Editors:

Michael Massing’s “The War on Cocaine” described the complexities of the international drug trade and made several important points:

—The cost in lives to Colombian officials and law enforcements personnel in the war against narcotics. In the past four years, more than 3,000 Colombian military and police personnel have been killed or wounded and a Justice Minister and an Attorney General have been gunned down.

—The limits of law enforcement in dealing with the complex chain on narcotics production, processing and distribution in Colombia and Latin America.

—The volatile mixture of guerrillas and narcotics traffickers which has brought so much violence to our country.

—The effect Colombian government programs have had in controlling the materials used in coca production which has made processing the drug less profitable.

—The need for more resources to fund crop substitution, rural credit and road building programs so that coca farmers have a viable alternative to growing coca.

Mr. Massing’s article also touched on the great wealth of the drug barons in Medellín—a center of the drug trade. There is no question that some individuals have amassed tremendous fortunes from drugs, and Medellín’s apartments and shops catch the eye of every journalist covering the drug story.

But it is important to underscore that while a few individuals may profit greatly, overall, drug monies have a negative effect on the Colombian economy. The recent solid Colombian economic growth has been in spite of, rather than because of, illicit drug profits.

Consider Medellín: While a few live as never before, the majority of Medellín’s citizens have suffered a drop in their standard of living over the last few years. Both textile mills and the small factories that had started up in the mid-Seventies to export machine tools have fallen on hard times. Skilled workers once employed in these operations are now either out of work or underemployed as waiters and domestics.

As Medellín’s mayor, Juan Gomez Martinez, explained earlier this year, the drug barons have not filled the gap left by the demise of Medellín’s industrial base. “Their money hasn’t created much employment because they haven’t invested in productive infrastructure,” he observed. Spending on imported bathroom fixtures and expensive art doesn’t translate into jobs for skilled tradesmen in Medellín’s factories, he noted. Nor, he might have added, do the drug lords pay taxes on their illegal earnings, yet their presence has forced the city the sharply increase spending on police, emergency medical services and other social services.

Another adverse effect of drugs has been on the cut-flower business where, because cocaine can be easily hidden among the flowers, security costs have skyrocketed. The rising costs and the delays at Customs in the US have put a crimp in what has been the fastest growing export sector in Colombia.

The empty factories in Medellín and the set-backs Colombia’s flower trade has experienced in recent years are two visible ways drugs have damaged Colombia’s economy. At a recent seminar at the Wondrow Wilson international Center for Scholars in the Smithsonian Institution, I asked a group of economists to consider the less visible ways in which drugs have affected the economy of Colombia.

Dr. Miguel Urrutia, an official of the Inter-American Development Bank and former Minister of Planning in the government of Colombia, offered one reason why drugs provide no basis for economic development. “Drugs have few linkages with the rest of the economy,” he explained. Cocaine, for example, does not demand a large investment in infrastructuring to bring it from the interior nor does it require a great deal of labor to process. By contrast, Colombia’s legitimate exports, like coffee and textiles, are linked to many other sectors of the economy.

Advertisement

With coffee, for example, railroads must be constructed and expensive processing facilities built. Textiles are not only labor intensive but create demand for raw materials and machinery. Growth in the coffee or textile sector fuels growth in the other sectors of the Colombian economy. Not so in the case of cocaine or marijuana.

Francisco Thoumi, an economist with the Inter-American Development Bank, sharply questioned the figures which suggest Colombia earns billions every year from the drug trade. Mr. Thoumi noted that much of the profit from the drug trade is earned “downstream” in the United States and other consuming countries as the drugs pass through various stages in the distribution chain. What’s more, there are indications that much of this money either remains in the United States, often reinvested in real estate or other legal businesses, or ends up in banks in Panama, Switzerland or other offshore banking havens. He expressed doubt that anything near $1 billion per year was actually repatriated to Colombia.

Urrutia, the former Planning Minister stated that even the funds that were returned to Colombia were of no help to the economy. The influx of drug dollars into the economy has spurred inflation. It has also given Colombia a variety of what the economists call the “Dutch disease.” Just as a sudden surge of income from natural gas exports in the late Seventies distorted the value of the Dutch guilder and made many Dutch exports uncompetitive, so the influx of the drug dollars has driven up the value of the Colombian peso, pricing Colombia’s legal exports like flowers and textiles out of world markets.

Drugs have cost Colombia dearly—in human terms, in social terms—and as the Wilson Center forum made clear, in economic terms as well. Thus, it comes as no surprise that the overwhelming majority of Colombians categorically reject any association with drugs or drug money. In a recent survey in Colombia over 80 percent opposed the legalization of either cocaine or marijuana, and 62 percent identified narco-trafficking as the major problem facing Colombia today.

The government of Colombia and its law-abiding citizens will continue to wage all-out war on drugs and drug trafficking. But it is a war we cannot win by ourselves. We must form an alliance with the governments, and the citizens, of the drug consuming nations of the world. And this means first and foremost the United States. If there is one central element in the drug trade, it is demand in the US—which consumes 50 percent of the world’s illicit cocaine.

Until this demand is forced down, the illegal profit incentive will eclipse the efforts made on all other fronts and violence and corruption in both our countries will continue to spiral up.

Only when the governments and the peoples of the supplier and consumer nations are fully united in an effort to halt both supply and demand will victory in the war on drugs be possible.

Victor Mosquera Chaux

Ambassador

Embassy of Colombia

Washington,DC

Michael Massing replies:

It goes without saying that the drug trade has had many negative consequences for the Colombian economy. The cocaine business in an inherently nonproductive enterprise, with much of its revenues going for things like bribery, assassinations, and gold faucets. But I think the ambassador greatly understates the magnitude of the Colombian drug business. Assigning a precise dollar figure is impossible, of course, but the estimates he cites are at the very low end of the scale. For instance, Bruce Bagley, a specialist on Colombia at the University of Miami, estimates that $2.5–$3 billion in drug profits are repatriated to Colombia every year, making narcotics more important than even coffee as a foreign exchange earner.

The government itself has been so eager to tap drug revenues that it has established special banking windows at which narco-dollars can be deposited, no questions asked. These deposits are probably one reason why the Colombian government has not had to reschedule its foreign debt. Colombia’s own controller general, Rodolfo Gonzales, has publicly hailed the contribution that drug money has made to the national economy. And, with every passing month, the influence of the narcos grows. According to some estimates, they now own as much as one twelfth of all productive farmland in the country. As The Washington Post noted in a January 8, 1989, article, “One of Bogotá’s four principal television stations and a nationwide chain of radio stations is controlled by the traffickers]. So are car dealerships, supermarkets, office buildings, discount drug stores—and at least six of Colombia’s professional soccer teams.”

The narco influence is nowhere more apparent than in Medellín. It’s not surprising that the mayor of Medellín would downplay the job-generating impact of the drug trade—it’s in his interests to do so. Many other local observers see it differently. In my article, I cite one estimate that the city’s unemployment rate would double in the absence of drugs. It’s precisely because of the slump in the city’s traditional industries that cocaine has taken on such importance.

None of this is to overlook the sinister nature of the drug business. The narco-traffickers are ruthless thugs who have succeeded in corrupting and intimidating government officials at every level. The polls cited by the ambassador state the obvious—that most Colombians are disgusted by the destruction wreaked by the cocaine business. Unfortunately, the government has been unable to do anything about it, forcing many citizens into a state of resignation.

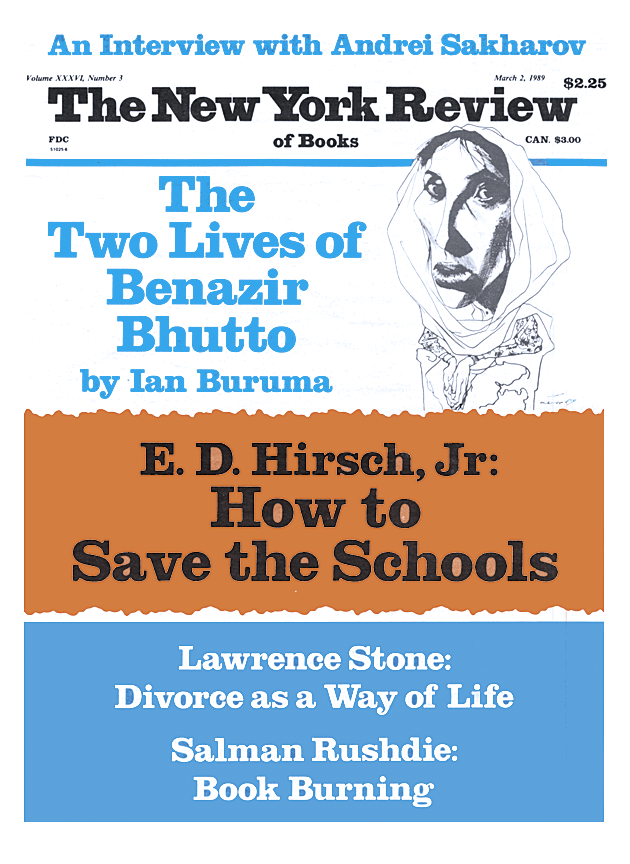

This Issue

March 2, 1989