Muriel Spark is a theological writer. Her doctrine lies concealed in the rococo parables she tells. So an account of her novels has to be an exegesis—quite likely a mistaken one. She might enjoy that. Her attitude to her readers is genially sarcastic, her manner crisp, dry, and light as a biscuit. Symposium is about a young middle-class Scottish witch. “In Scotland,” says her mad uncle Magnus, “people are more capable of perpetrating good or evil than anywhere else”; and so the novel is punctuated by sinister snatches from Scottish ballads. Magnus is debonair, wicked, quite rational when properly sedated, and content with his life in a mental home. Every Sunday he comes out to lunch with Margaret’s parents in St. Andrews: he has a special affinity with his niece. He knows she has the evil eye before she guesses it herself, and takes it upon himself to direct her into serious, planned evil doing. Until his intervention, she has only been involuntarily and inexplicably connected with violent deaths: two at her boarding school, then her grandmother’s murder by a psychopath from the secure wing of Magnus’s institution (presumably sprung by him), and finally the strangling of a young nun at the convent which she joins as a novice.

The convent is recycled from the community in The Abbess of Crewe, but the second time round the swearing, blaspheming, chain-smoking, Marxisant nuns have lost some of their power to shock and amuse. They are only an Anglican order, anyway. They concentrate on housework and hospital visiting instead of prayer and liturgy. Spark likes to signal her contempt for the goodworks side of religion as opposed to the theological side, and the community in Symposium is duly punished. Young Sister Rose shares Spark’s views: when a television crew arrives to make a program about the convent, she complains on camera that there is not enough “spiritual life” and that the nunnery is “virtually nothing but an entity in the National Health Service.” At this, the moribund Mother Superior summons up sufficient strength to strangle Sister Rose before breathing her last. The result is that the convent has to be closed down.

Margaret returns to St. Andrews at a loose end and has a seminal talk with Magnus:

“I’m tired of being the passive carrier of disaster. I feel frustrated. I almost think it’s time for me to take my life and destiny in my own hands, and actively make disasters come about….”

“Perpetrate evil?” Magnus offered.

“Yes. I think I could do it.”

“The wish alone is evil,” said Magnus with the distant equanimity of a college tutor who has two or three other students to see that afternoon.

“Glad to hear it,” said Margaret.

Magnus begins by producing a list of rich eligible bachelors for Margaret to marry. She picks “a junior researcher in artificial intelligence, the bionics branch.” His work comes to fascinate her; she suspects it might have a useful bearing on witchcraft. But the reason William Damien got onto Magnus’s list in the first place is that his widowed mother Hilda is an Australian multi-millionairess. Margaret has long red hair and sexy buck teeth and easily captures William in the fruit section of the Oxford Street branch of Marks and Spencer’s. They have just returned from their honeymoon when they are invited to a dinner party by Hurley Reed and Chris Donovan.

Chris is another rich Australian widow, and Hurley is a Catholic American painter. “There was probably nothing more pleasant in the whole of London than the charming love between Hurley Reed and Chris Donovan.” Only one or two extremely rich characters in the novel are at all likable, which is unusual and possibly significant. Chris and Hurley have lived together, unmarried, for many years. The novel centers on their dinner party (the Symposium of the title): most of the characters are present, either as guests, hosts, or servants. Their histories—including Margaret’s—are filled in bit by bit. Their conversation touches on some of Spark’s favorite topics, such as the rationality of Catholicism and the indissoluble nature of marriage. The food and its service receive a lot of attention: altogether the novel has a consumer side, being much—and generally sarcastically—concerned with clothes and decor. We might be reading Tom Wolfe writing captions for The World of Interiors.

Symposium comes on like a thriller. Its sociability reminds one of Agatha Christie, its sophisticated menace of P.D. James; both resemblances are very likely deliberate. Early on one guesses that someone will be murdered; a third of the way through, one knows who it will be:

“Your mother’s coming on after dinner,” Chris says to William Damien.

“Good,” says Hurley.

But Hilda Damien will not come in after dinner. She is dying, now, as they speak.

The statement is very shocking in its context, far more than the actual murder at the end of the novel. Sparks gimmick is that although the crime is foreshadowed, two separate plots face toward it, and the winner is not declared until the end. One plot is Margarette intention to push her mother-in-law into a pond when she comes to St. Andrews for the weekend after the dinner party; Magnus is to help hold her face down in the mud. The other emanates from Chris and Hurley’s butler and the charming young American graduate student who helps him wait at table and sexually attracts married guests of both genders. The butler and the student act as informers to a gang of burglars who specialize in cleaning out apartments while their owners are at dinner parties. There is no intention to kill Hilda Damien: it is simply unfortunate that she delivers William and Margaret’s wedding present—a Monet painting—to their flat just as the burglars arrive. They are caught almost instantly, and a police officer interrupts Chris and Hurley’s dinner to break the news of his mother’s death to William. “No, it can’t be,’ Margaret shrieks. ‘Not till Sunday.’ ”

Advertisement

A final, mournful paragraph describes the grief of Andrew J. Barnet, another multimillionaire. Hilda had met him in the first-class section of the plane to England. He had sent flowers to her at the Ritz, and was planning to take her out to dinner. “He will remember her on the plane, attractive, and so used to wealth and success that everything was easy between them as they talked. Like speaks unto like.” Hilda had actually picked him out as a potential second husband. If this novel has a lesson, it seems to be the one about “the best laid schemes o’ mice and men,” and even witches. The author of that line, Robert Burns, is a Scot.

Spark’s main theme is the prevalence of evil. She has broached it many times before. In her last novel, A Far Cry from Kensington, the regular perpetrator of evil caused a suicide. His punishment was to be ignored—by the nice characters who abandoned the idea of persecuting him, and by the author, who let him slip out of the story. There is nothing to be done about evil, she seemed to be saying, and she says it here again. It exists and can’t be helped. It is not our place to judge it. Margaret has not chosen to have the evil eye; when she actually decides to use it, it doesn’t even work. She is the antithesis of Spark’s last heroine, Nancy Hawkins, who could not help doing good. Spark is always discussed as a Catholic writer, but sometimes she seems closer to another Scot, the Predestinarian James Hogg.

There is nothing gloomy about her, though. Most of her novels have an exuberant intellectual gaiety about them, and the more restrained ones engage us by virtue of a faint, light-hearted, and quite unsentimental warmth. The wilder ones tend to be farcical, heartless jeux d’esprit. Symposium falls into this category. It is full of jokes. Some depend on the incongruous juxtaposition of modern and ancient elements: bionics and witchcraft, nuns on television. This can lead to a thoroughly modern Millie effect, with the author demonstrating how au fait she is with the very latest developments and manners.

Spark has made things difficult for herself in Symposium by having quite a large cast perform over a very short novel, and by allotting each member about the same amount of weight and space. Margaret is a catalyst, but she is brought no nearer to the reader than the rest. All are kept at a distance—you could call it a safe distance, since they never come close enough to elicit either empathy, sympathy, or dismay. Their trajectories are cunningly intertwined to make a pretty ballet, and indeed one can imagine the novel turned into a ballet. A Far Cry From Kensington had an untidy structure and an appealing heroine. It was a better formula for a novel.

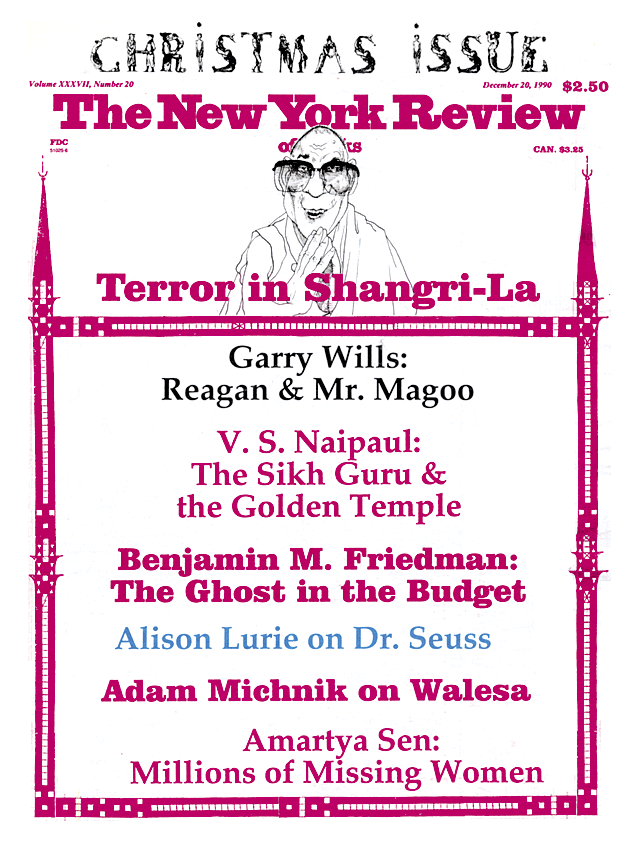

This Issue

December 20, 1990