Young and fashionable crowds spilling over into the street, turned away nightly after vain attempts to gain admission to The Lady Eve or Christmas in July: such was the unanticipated spectacle provided by a recent Preston Sturges retrospective at New York’s Film Forum, which ended going into overtime in order to accommodate the eager hordes. Out in the lobby, alongside copies of the newly published memoir Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges, a collection of memorabilia testified to Sturges’s success at shaping his own legend, from his invention of a kissproof lipstick to his elopement with the Hutton heiress (an escapade which made the front page of The New York Times). In each of the photos on display Sturges managed to turn himself into a perfectly judged comic icon, an amalgam of whimsical moustache and flamboyant headgear, the glittering eyes promising initiation into unimaginable realms of gnostic zaniness. It was a sweet triumph, however posthumous and belated: Sturges presented entirely on his own terms, enjoying the unconditional success he courted so energetically.

The retrospective—assembling nearly all the movies he directed, wrote, adapted, inspired, or (in one instance) wrote subtitles for—was above all a festival of language. The inclusion of films written for other directors (like Diamond Jim and Remember the Night) or adapted from his plays (like Strictly Dishonorable and Child of Manhattan) focused attention on Sturges as a literary figure, a playwright who switched to movies because they were “handy and cheap and necessary and used constantly…instead of being something that one sees once on a wedding trip, like Niagara Falls or Grant’s Tomb.” From the speakeasy of Strictly Dishonorable, Sturges’s 1929 Broadway hit, to the tavern of the late and commercially disastrous The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, of 1947, and most especially in the eleven features he wrote and directed between 1940 and 1948, his abstract interiors hum to the most consistently lively dialogue that any American has written for stage or screen. Who else wrote such distinctive lines? The juxtaposition (in Remember the Night) of yodeling, bubble dancers, corsets, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “My Indiana Home,” hypnoleptic catalepsy, and the remark “In China they eat dogs” establishes more clearly than any screen credit what territory we are in.

It is peculiar that movies made only a few decades ago have attained an almost Elizabethan richness and strangeness—at least in comparison with the monosyllabic dialects of today’s screenplays. Sturges was hardly unique in his mix of high and low diction, his keenness for the verbal peculiarities of senatorial orators and gum-chewing soda jerks, of backwoods preachers and polyglot card sharps. The talents of Ben Hecht, Jules Furthman, S.J. Perelman, George S. Kaufman, Morrie Ryskind, Clifford Odets, Robert Riskin, Charles Brackett, and countless others combined to create that vernacular palimpsest of the Thirties and Forties which has so often been pastiched but never improved upon. Where Sturges stands out is in his degree of self-displaying stylization. He breaks every rule of movies by putting language at the center and making the whole film swirl around it.

For all that he learned from screwball directors like Gregory La Cava and Leo McCarey, Sturges never emulated their improvisatory approach. Every line had to be delivered precisely as written. His direction of actors took place inside his head, as he wrote lines tailor-made for the people who would be reading them. His stock company of character actors became extensions of himself, as if his unconscious could bubble forth most naturally in the accents of Porter Hall or Jimmy Conlin or William Demarest. The result is a sense, rare in movies, that all the characters have been conceived by a single mind: it is a universe of logomaniacs, keeping themselves alive by speech, and each is some form or aspect of Preston Sturges.

The saturated texture of his movies does not come primarily from visual effects or expressive acting. Indeed, often he deliberately flattens both photographic space and vocal intonation in order to heighten the impact of what is said. Straightforward, relatively unexpressive actors like Joel McCrea and Dick Powell are ideally suited to give him the kind of line readings he wants. Characteristically he plunges us into the middle of an animated dialogue, as if we walked into a room where an argument between strangers was going on. The three-way debate in the screening room in Sullivan’s Travels (an amazingly long one-take sequence), the noisy crisscrossing banter of the marines in Hail the Conquering Hero, the rooftop dialogue of the lovers in Christmas in July, the shipboard colloquies of Fonda and Stanwyck in The Lady Eve: these flurries of talk knock us off balance, forcing us into a mode of breathless attention in an effort to catch up.

The back-and-forth of what he called “hooked” dialogue went well beyond the norms of movie repartee. By the time we get to the end of his first acts we’ve already had a movie’s worth of language. The magnificence of his dialogue resides in what makes it difficult to excerpt. There are few one-liners or punchlines: the words careen off each other with manic expansiveness. In other comedies one laughs at specific gags. With Sturges, on the other hand, whole scenes and, at his best, whole films are suffused with an unbroken undercurrent of gathering hilarity: a mood which in Christmas in July or Hail the Conquering Hero is indistinguishable from the onset of an anxiety attack.

Advertisement

The sources of that anxiety have been raked over by a surprisingly large number of commentators: the Sturges literature already embraces two serviceable biographies (the one by Donald Spoto concentrates more on emotional portraiture, while Curtis fills in the show-business background), critical studies by James Agee, Manny Farber, André Bazin, and many others, an edition of five screenplays (with superb commentary by Brian Henderson)—and now, thirty-one years after Sturges’s death, a sort of autobiography. It is a curious book. Sturges undertook to write his memoirs in 1959, producing, according to his editor Robert Lescher, “an unfortunate manuscript…prolix, repetitive, often distasteful—really just terrible”; it only went as far as 1927. Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges is presumably a much-edited version of this draft (portions of which had previously shown up in the biographies by James Curtis and Donald Spoto) supplemented by material from letters, diaries, and magazine articles.

The surprisingly seamless result is certainly fun to read. On his worst day Sturges was capable of putting together absolutely amusing and satisfying sentences. He writes of his father, whom he barely knew: “Among his possessions was a revolver, with which he often threatened to shoot himself, and my mother, who didn’t like him, would urge him to go ahead.” Of his mother’s best friend Isadora Duncan: “Isadora met Gordon Craig and began a torturing relationship, apparently spawned in an irresistible physical attraction but nourished by their mutual adoration of the genius of Mr. Craig.” On his realization of the extent of his first wife’s wealth: “Much as I disliked the un-American idea of marrying a lady with a dowry, I must admit that little Mrs. Godfrey’s little private income put everything in a faintly different light.”

He revels in an ornate vocabulary, achieving wonderful little bursts of humor by the mere deployment of such words as “contumely” or “freebooter” or “pyrogravure.” All in all it is probably quite like listening to one of the after-dinner monologues in which Sturges would spin out tales of his remarkably hectic childhood and early youth: tales of the fractured years when he was shunted between his adoptive father, the Chicago businessman Solomon Sturges, and his mother, Mary Dempsey, who crisscrossed Europe in company with the beloved Isadora, while indulging in an extravagant succession of name changes (Dempsey to d’Este to Desti), marriages, liaisons, religious conversions, artistic epiphanies, and money-making schemes. From this childhood, which brought him into early contact with the likes of Enrico Caruso, Cosima Wagner, Elsie Janis, Theda Bara, L. Frank Baum, Evelyn Nesbit, and Lillian Russell, Sturges constructed a legend more frenetic than any of his scripts.

That so little of his inner life is revealed in these memoirs hardly comes as a surprise. He was by choice a man of brilliant surfaces, an ebullient figure who might have been invented by Feydeau or Lubitsch. The anecdotes intend to charm and amuse, not harp on pain or anger. Whatever suffering Sturges betrays he wraps in a wry and self-deprecating manner. But the feelings come through clearly enough, whether in a story about his shock upon learning at age eight that the adored Solomon Sturges was not his real father, or in his laconic summary of what followed: “Despite my express wish, I was not left in Chicago, but taken to Paris to live, and I did not see my father for many years.”

His father, he asserts, was the person he loved most; but that is about all he has to say about him. Of his mother there is much more to tell—in fact she manages to upstage her son in his own memoirs. She makes a marvelous character, a quintessentially Sturges character, with her mixture of scatterbrained enthusiasm and cold-blooded calculation. Keenly aware of what colorful copy she provides, Preston almost succeeds in transforming her into a lovable eccentric:

She was…endowed with such a rich and powerful imagination that anything she had said three times, she believed fervently. Often, twice was enough…. This then is what I mean by “according to my mother.” I would not care to dig too deeply in some spot where she indicated the presence of buried treasure, nor to erect a building on a plot she had surveyed.

On one level his mother’s outrageousness delights Sturges; the mere fact of accompanying her on her travels has made him a man of the world, rich in exotic experience. He depicts a woman whose grandiose artistic and spiritual aspirations did not detract from her skill as a hustler. Preston is quick to detect the ruthlessness under the aestheticism, and he makes it clear that for all Mary’s strenuously exercised joie de vivre, she had little interest in tending to the emotional needs of her son, who was parked with a series of random caretakers while Mary took off. The closest he comes to a direct accusation is this: “Every so often a beautiful lady in furs would arrive in a shining automobile with presents for everyone. This was Mother, of course…. After a little while, I would be able to talk to her haltingly in English.”

Advertisement

It would be poor form for him to show his hurt any more bitterly, but he gets revenge by his satiric demolition of everything she took seriously. His accounts of her husbands and lovers leave an aftertaste of sullen jealousy, exploding into outright (and understandable) rage when he comes to her brief but intense involvement with the notorious self-proclaimed necromancer and antichrist Aleister Crowley:

Generally accepted as one of the most depraved, vicious, and revolting humbugs who ever escaped from a nightmare or a lunatic asylum…Mr, Crowley nevertheless was considered by my mother to be not only the epitome of charm and good manners, but also the possessor of one of the very few genius-bathed brains she had been privileged to observe at work.

Attempting to account for this fascination, he can only surmise that “my mother was still a woman, one of that wondrous gender whose thought processes are not for male understanding.”

Anger rarely shows itself so openly; but perhaps Preston was saving up his wrath in order to vent it through his comic surrogates. The real laughs in his movies come most frequently from the choleric outbursts—modulating every variation of peevishness, sarcasm, bluster, and barroom gruffness—of Raymond Walburn, Al Bridge, Franklin Pangborn, Lionel Stander, Akim Tamiroff, and most indispensably William Demarest, without whose insistent rages Sturges’s comedy is hardly conceivable. The sheer satisfaction of expressing unbounded hostility and contempt finds its culmination in Rex Harrison’s flight of invective in Unfaithfully Yours, upon discovering that his brother-in-law (the hapless Rudy Vallee) has had Harrison’s wife followed by detectives:

You stuffed moron!… You dare to inform me that you have had vulgar footpads in snap brim fedoras sluicing after my beautiful wife?… This is the sewer, the nadir of good manners!… Now get out of here and never speak to me again unless it’s in some public place where your silence might cause comment or embarrassment to our wives!

Sturges’s presence is strangely muted in his account of his tumultuous childhood. He emerges at the end of it as a young man with perfect manners, an apprentice voluptuary with a fluent knowledge of French, a flair for mechanical tinkering, and no clearly defined ambition. He had been marked indelibly by the fashionable world he glimpsed at Deauville in the summer before World War I—“dukes, barons, deposed kings…notorious actresses, vaudeville performers, gigolos…playwrights, publishers, gamblers”—and subsequently strove to live up to the dandyish ideals of a vanished epoch.

It would take him until the early Thirties—after two marriages to heiresses who walked out on him (two other marriages and countless affairs would follow), a long stint running his mother’s cosmetics business, an abortive career as a songwriter, a hit Broadway play, and three resounding Broadway flops—to get out to Hollywood and begin his career in earnest. But the years of his greatest success get scant treatment in Preston Sturges by Preston Sturges; for a continuation of the autobiography it’s necessary to consult the films themselves.

The organized chaos of Sturges’s movies reflects the circumstances of his life quite accurately. He slept little, went to many parties, designed a house, sailed a yacht, took out patents on all manner of not-quite-successful inventions, ran a restaurant (later expanded to include a theater) and, at least nominally, an engineering company. Yet the only matter in which he was really out of control was the spending of money—the cash he poured into the restaurant finally ran him into the ground. Otherwise the anarchic surface of his life seems to camouflage a rather successful effort to direct the behavior of those around him. Whether as filmmaker, dinner host, or raconteur, he was apparently able to mold most social gatherings into his image of the ideal party. According to Eddie Bracken, “Sturges was always on stage. Always.” “He was not as good a listener,” said William Wyler, “as he was a talker.” Another friend remarked, speaking of a later and darker period, “We somehow didn’t do things unless he suggested we do them.”

A genius of personal publicity adept at stage-managing his interviews, treasuring every bit of memorabilia, he was a man who scripted his own life. Despite the dutiful efforts of Curtis and Spoto to include his less attractive side, the sour notes (and his emotional relationships were full of them) remain powerless to undermine the charm of Sturges’s self-presentation. Consider his approach to the husband of the woman who would become his third wife, as recounted by Curtis: “‘Sir,’ greeted Sturges, bowing deeply at the waist, ‘I have the honor of requesting the hand of your wife in marriage.”‘ There can be no doubt that such moments were as carefully crafted as any of his comedies.

This exertion of personal control distinguishes the chaos of his adulthood from that of his childhood. The wild party continues, but now he is at its center rather than its periphery. After learning about the world through the medium of his mother’s chaos, he successfully constructed a chaos to his own specifications. Instead of surrounding himself with the truly eccentric and over-bearing personalities in his mother’s circuit, he often sought out more malleable types so as to remain the focal point of most occasions. Like the wild outbursts in his movies which were in fact scripted down to the last interjection, the impression he created of making up his life as he went along appears to have been the product of a tenacious discipline.

What lingers finally from his movies is not their wildness but their unsentimental rigor. His best scripts function like traps snapping shut. Like a poker player who does not allow his attention to be disturbed by transitory runs of good luck, he has his eye out for the main disaster. The fates that hang over his characters—Dick Powell’s discovery that he hasn’t really won the contest on which he’s staked his whole being (Christmas in July), Eddie Bracken’s humiliating exposure as a fraud before his family and community (Hail the Conquering Hero)—verge on being too painful for comedy. While Sturges does manage to throw together satisfactorily happy conclusions, there are no emotional outpourings in the manner of Capra—simply a sense of having narrowly missed going over the edge. Even Conquering Hero, which risks the most and therefore has the most patching up to do, cannot salve the suspicion that next time Eddie Bracken may not be so readily forgiven for his shortcomings.

No one is particularly safe in a world where everyone is out for himself. “It is probably a very good thing,” writes Sturges of his school days, “for a boy to learn to live with enmity, as opposed to an atmosphere of love and affection, as it hardens him and gives him a taste of what he is going to run into later in life.” Selflessness is in exceedingly short supply in Sturges’s movies. (Shortly before her death, Mary told Preston: “I was only trying to find happiness.” He leaves unspoken the implicit rejoinder: Hers, not his.) The nice people, the innocents, are ultimately as self-seeking as the grafters and bunko artists. The priggishness of Henry Fonda’s snake-collecting naif in The Lady Eve proves more malevolent than the open crookedness of Barbara Stanwyck. But Sturges doesn’t simply reverse the values. The witty father-and-daughter team of con artists is enchanting, but when Stanwyck falls in love with Fonda, her father (the genial Charles Coburn) reveals a more cold-blooded side. Love is real enough in Sturges’s world, but its limits and conditions are carefully observed.

The penalty for breaching the rules is an aloneness without reprieve. William Demarest, who worked closely with Sturges on most of his features before a quarrel ended their relationship, commented bitterly: “He never left you with anything. He was like a separate thing walking around by himself. I don’t think he had any love for anybody.” This may not be a fair description of Sturges, but it certainly fits a good many of his characters.

The other side of his humor was an O’Neill-like despair most evident in the 1933 screenplay The Power and the Glory, an experimental treatment of a go-getting businessman whose inner emptiness leads to suicide. Another of the more interesting Thirties scripts, Diamond Jim, also revolves around a successful man (Edward Arnold as Diamond Jim Brady) who chooses to commit suicide, albeit of a comically apt variety: he gorges himself to death at a solitary banquet. Husbands, achievers, and men of power who slide from grace crop up in The Great McGinty, The Palm Beach Story, The Great Moment, The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, and in the few emotionally convincing moments of Sturges’s last and least movie, the French-made The Notebooks of Major Thompson. The most frenzied of the comedies are punctuated by dark, marginal instances of an anomie elsewhere held under control by the sheer will to liveliness.

The ever-present possibility of failure can be kept at bay, when all else fails, only by Sturges’s limitless verbal imagination. Until the very end of his career—when a decade of rejections and false starts began to chip away even at his boundless self-confidence—Sturges retained the sense that he could retrieve his career at any time by sitting down at the roadside and coming up with a story. His faith in his own creative hunches, fortified by a belief in lucky streaks and magic coincidences, enabled him to live a life on the edge, ready to stake everything on the next story idea.

Imagination becomes a form of currency, negotiable as houses, yachts, and restaurants. He can control the world with words. His films depict an arena where politicians, con artists, salesmen, attorneys, inventors, and seducers make a place for themselves through language alone. Barroom eloquence, gutter invective, patriotic hyperbole, the effusions of courtship: all invent instant plenitude, an all-American gratification that redeems an otherwise squalid existence.

“I’m not a failure,” intones the office manager in Christmas in July, “I’m a success…. No system could be right where only half of one per cent were successes and all the rest were failures.” But neither Dick Powell, Sturges, nor the audience believes him for a minute. Success must be had at any price, even at the price of faking it. Sturges’s main characters are mostly frauds: Woodrow in Conquering Hero assuming the trappings of a battle-scarred marine, the card sharps in The Lady Eve reveling in aliases and fictitious origins, the director in Sullivan’s Travels even adopting a fraudulent poverty. The writer’s advantage is that he can admit to what everyone else conceals: that he operates under a set of false pretenses.

A combination of unfortunate circumstances prevented Sturges from exercising his talents in his final years. The memoirs, fragmentary as they are, must stand in for all the movies that didn’t get made. One final passage might be the narration for the last one of all. One can easily imagine Joel McCrea doing the voice-over with his inimitably flat delivery:

“A man of sixty, however healthy, makes me think of an air passenger waiting in the terminal, but one whose transportation has not yet been arranged. He doesn’t know just when he’s leaving. While waiting, he thinks back on his life and to him it seems to have been a Mardi Gras, a street parade of masked, drunken, hysterical, laughing, disguised, travestied, carnal, innocent, and perspiring humanity of all sexes, wandering aimlessly, but always in circles, in search of that of which it is a part: life.”

It was somehow in keeping with Sturges’s destiny to have the rare privilege of scripting his own death scene. After this he adds:

These ruminations, and the beer and coleslaw that I washed down while dictating them, are giving me a bad case of indigestion…. I am well versed in the remedy: ingest a little Maalox, lie down, stretch out, and hope to God I don’t croak.

He died twenty minutes later.

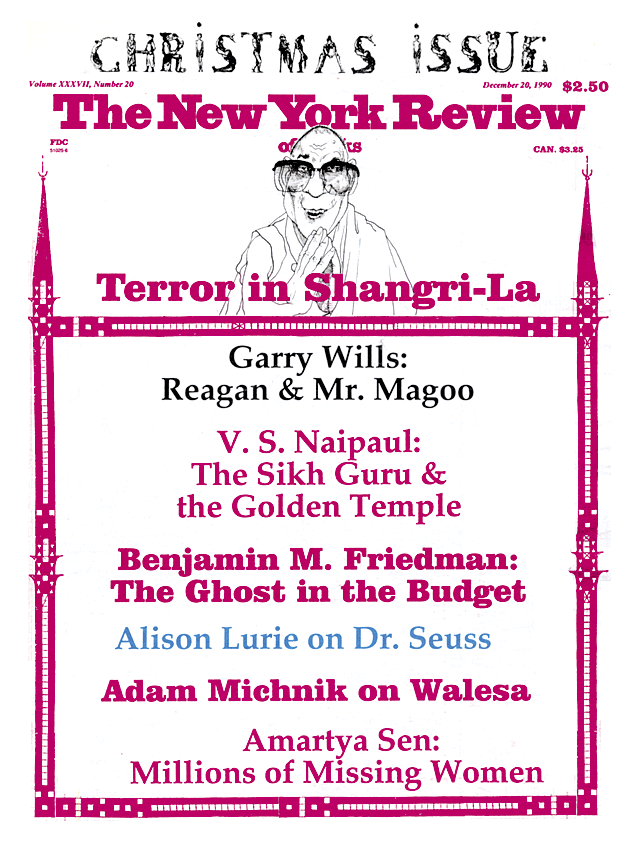

This Issue

December 20, 1990