In response to:

The Thief of Baghdad from the September 27, 1990 issue

To the Editors:

In our book Iraqi Power and U.S. Security in the Middle East we questioned whether Iraq had used chemicals against its Kurdish population, as widely believed. Your reviewer (Edward Mortimer, “Republic of Fear,” NYR, September 27) challenged us on this. Since it is a matter of some importance, we would like to offer support for our view. Essentially there are two instances under scrutiny. The first attack allegedly occurred at Halabjah in north-central Iraq. All accounts of this incident agree that the victims’ mouths and extremities were blue. This is consonant with the use of a blood agent. Iraq never used blood agents throughout the war; Iran did. The U.S. State Department said at the time of the Hallabjah attack that both Iran and Iraq had used gas in this instance. Hence, we concluded it was the Iranians’ gas that killed the Kurds.

The second alleged gas attack by the Iraqis against the Kurds occurred at Amadiyyah (in the far northern region of Iraq) after the war had ended. This one is extremely problematical since no gassing victims were ever produced. The only evidence that gas was used is the eye-witness testimony of the Kurds who fled to Turkey, collected by staffers of the U.S. Senate. We showed this testimony to experts in the military who told us it was worthless. The symptoms described by the Kurds do not conform to any known chemical or combination of chemicals.

Lacking any gassing victims, and given the fact that the testimony does not seem credible we were unwilling to say that in fact the attacks had occurred. At the same time, throughout the study we cited instances of Iraqi-instigated chemical attacks against Iranian military units. There is no doubt that these occurred; indeed the Iraqis have stated on occasion that they feel justified in using chemicals tactically under certain conditions. However, they deny using chemicals as a weapon of mass destruction, that is against civilians. What our study concludes is that those who claim they are doing so need to come up with some more convincing proof.

On an another matter, your reviewer claimed that we did not predict the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. He quotes us (correctly) as saying that (after the war with Iran) “Iraq has neither the will nor the resources to go to war with anybody.” However, we qualified that statement, by saying, if we (that is the United States) impose economic sanctions on the Iraqis, it then is likely that they will lash out against our interests in the Gulf. This part of the prediction your reviewer left out, and it’s important since, as you know, the U.S. Congress did impose sanctions and almost immediately after the Iraqis invaded Kuwait.

If any of the New York Review of Books readers want to read what we said in our study, they can obtain a free copy by writing to us.

Dr. Stephen C. Pelletiere

Lt. Col. Douglas V. Johnson III

Strategic Studies Institute

US Army War College

Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, 17013–5050

Edward Mortimer replies:

I accept that in the specific case of Halabja the possibility that the chemical attack came from Iran (which might not have realized that Iraqi troops had already evacuated the town), or indeed from both sides consecutively, cannot be ruled out. I find it extraordinary, however, that the War College authors persist in dismissing the evidence that Iraq’s armed forces used poison gas against Kurdish civilians and insurgents in late August 1988, i.e., after the end of the war with Iran. This evidence takes a number of forms:

1. State Department officials said on September 8, 1988, that US intelligence agencies had confirmed Iraq’s use of chemicals in its recent drive against Kurdish civilians in Northern Iraq. The same information prompted Secretary of State George Shultz, a man who had presided over a strong pro-Iraq tilt in US policy, and who continued to oppose sanctions against Iraq, to accuse Iraq of “unjustifiable and abhorrent” use of poison gas against the Kurds in a meeting on the same day with Iraqi Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Saadoun Hammadi. (This evidence was shared with the British government, and was subsequently described as “compelling” by then Foreign Secretary Sir Geoffrey Howe.) Although there was vigorous debate between Congress and the executive branch about the policy conclusions to be drawn, in 1988 and again in 1990, there has been no difference between them about the facts of Iraqi misconduct.

- Many eyewitness accounts were collected in Turkey between September 11 and 17, 1988, by a Senate Foreign Relations Committee staff mission led by professional staff member Peter W. Galbraith and including a representative of the State Department as well as a Kurdish-speaking US government employee. This team interviewed refugees (men, women, and children) from more than thirty villages—some selected by Kurdish refugee leaders but many others chosen at random by the team itself. Most refugees said that they had seen the attacks and resulting deaths. Their accounts were striking for their detail and consistency: people from the same village who had found refuge in different parts of Turkey gave similar accounts of the attacks on their village; and survivors from different villages described a similar pattern of Iraqi attack and victim symptoms. As Galbraith says in a recent memorandum sent to The New York Review: “To disbelieve these eyewitnesses one would have to conclude that the Kurdish insurgents had organized, in a matter of days, a conspiracy to defame Iraq involving the full participation of 65,000 men, women, and children confined in camps in locations up to 200 miles apart.”

The War College authors cite unnamed “experts” as saying the symptoms described by the Kurds do not conform to any known chemical or combination of chemicals. But US government experts consulted by the Senate mission said that the symptoms described were consistent with the use of mustard gas, as well as some fast-acting lethal agent, possibly nerve agents or cyanide.

- These findings were supported in congressional testimony by Dr. Robert Cook-Deegan of Physicians for Human Rights, who led a medical team to eastern Turkey. Contrary to the assertion of the War College authors, this team of doctors was able to examine actual victims of the attacks, and found injuries resulting from blistering agents.

- Further eyewitness testimony was collected from refugees in Iran by British journalist Gwynne Roberts, and shown on British Channel 4 television on November 23, 1988. Survivors described a massacre at Bassay Gorge, in northern Iraq, on August 29, 1988, in which something between 1,500 and 4,000 people, mainly women and children, were killed by what appears to have been a mixture of various nerve gasses while trying to reach the Turkish border. Their bodies were piled up and burnt by Iraqi troops wearing gas masks the following morning.

Roberts, a very experienced reporter, said the survivors were clearly traumatized by what they had witnessed, and their reports were completely consistent. He also entered Iraq clandestinely and brought back fragments of an exploded shell with samples of the surrounding soil, which were confirmed by a British laboratory as containing traces of mustard gas. (Nerve gas would not have left traces so long after the event.) In my review I drew attention to the fact that Roberts’s evidence was completely ignored in the report of the War College authors, and I note that it is still completely ignored in their letter.

Even more extraordinary is their attempt to suggest that the US Congress provoked the invasion of Kuwait by imposing sanctions on Iraq. In fact, Congress had not enacted sanctions by the time Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2. It seems far more likely that Saddam Hussein went ahead with the invasion because he believed the US would not react with anything more than verbal condemnation. That was an inference he could well have drawn from his meeting with US Ambassador April Glaspie on July 25, and from statements by State Department officials in Washington at the same time publicly disavowing any US security commitments to Kuwait, but also from the success of both the Reagan and the Bush administrations in heading off attempts by the US Senate to impose sanctions on Iraq for previous breaches of international law.

Events have tragically borne out the warning in the report of the Senate mission in September 1988, which said: “Right now the Kurds are paying the price for past global indifference to Iraqi chemical weapons use; the failure to act now could ultimately leave every nation in peril.” On that occasion the US, and the rest of the international community, failed to act. Now soldiers of the US and many other nations face a chemically armed Iraq, on the Saudi-Kuwaiti border.

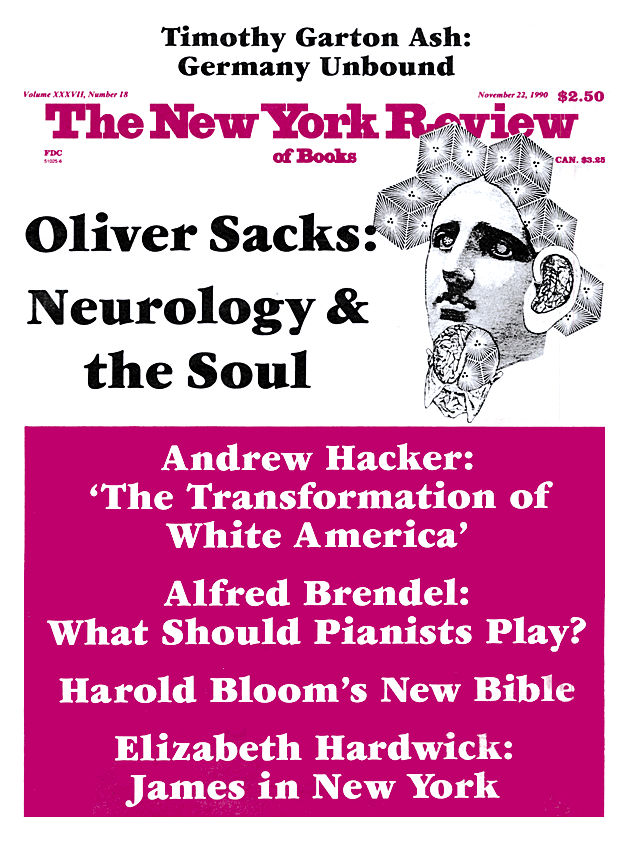

This Issue

November 22, 1990