1.

Frank Auerbach is one of the most admired artists working in England today. Perhaps if his career says anything about “the art world,” it confirms its irrelevance to an artist’s growth.

Auerbach entered a London art school forty years ago, as a teen-ager. Since then he has done nothing but paint and draw, either from the posed model or from quick landscape scribbles done outside, ten hours a day, seven days a week, in the same studio in northwest London. Most of his paintings are of people who pose for him in London or are of places in London. He has hardly any social life beyond his contacts with a small circle of other artists in London: Leon Kossoff, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, R.B. Kitaj. He does not teach. He has traveled very little. To be on any kind of international circuit is and always has been alien to Auerbach: the museums he has not been to would include the Prado, the Hermitage, the Uffizi, and all American ones except—during two brief visits to New York in 1969 and 1982—the Metropolitan, the Frick, and the Museum of Modern Art. He has been to Italy twice, the first time for a show of his work in Milan in 1973, the second for his exhibition in the British Pavilion at the 1986 Venice Biennale. The first visit took a week and the second four days, including a trip to Padua to see, for the first time, Giotto’s frescoes in the Arena Chapel.

On the other hand, Auerbach’s attachment to the National Gallery in London is deep and almost fanatical; throughout the Fifties, Sixties, and Seventies he and his friend Leon Kossoff kept up what struck other artists and students as the quaint habit of going to Trafalgar Square at least once a week to make drawings from certain paintings there:

My most complimentary and my most typical reaction to a good painting is to want to rush home and do some more work…. Towards the end of a painting I actually go and draw from pictures more, to remind myself of what quality is and what’s actually demanded of paintings. Without these touchstones we’d be floundering. Painting is a cultured activity—it’s not like spitting, one can’t kid oneself.1

Auerbach’s feelings about the museum have nothing to do with the exploitable reverence, the idea of the museum as a secular cathedral, that has contributed so many grotesqueries to our institutional culture. He treats it as a writer treats a library: as a resource, a “professional facility.” “Your correspondents tend to write of paintings as objects of financial value or passive beauty,” he protested in a letter to The Times of London in 1971. “For paintings they are source material; they teach and they set standards.”2 There is perhaps no living artist more wholeheartedly in accord with Cézanne’s dictum that “the path to Nature lies through the Louvre, and to the Louvre through Nature.” Auerbach does not believe that modern art made a radical break with the past.

From Giotto until now it’s one school of art and I don’t think that necessarily the most radical twist occurred around 1907…. Géricault, Delacroix, Corot, Courbet, Ingres, Daumier—they came up with languages of a hitherto unknown disparity.3

These languages are alive to him, as the inherited languages of his or her medium must be to any serious artist. An interviewer in 1986 who incautiously asked what artists had influenced him got a Borges-like list of more than fifty names off the top of his head, of whom no more than a third had worked in the twentieth century and only two (Leon Kossoff and Francis Bacon) were alive. With some, one sees the affinity at once. The internal glow that works its way out of Auerbach’s heads is partly the result of long meditation on Rembrandt. There is much in common between the overloaded surfaces of early Auerbach paintings and the pelleted, molded skin of Giacometti’s bronzes, which were in turn fed by the harsh impacted blobbiness of Daumier’s tiny clay sculptures, Les célébrités du juste-milieu; and all three have in common a fiercely sustained remoteness as things-in-the-world, a disdain for the merely expressive. The way a single brush stroke turns, slaps, and becomes an autonomous sign for chin or cheek in Auerbach’s portraits of J.Y.M. in the 1970s puts one immediately in mind of the radical abbreviations in Manet and, even more, the twisting faces in the foreground of Goya’s Pilgrimage to San Isidro. The geometrical grids of Auerbach’s cityscapes of Camden Town have Mondrian in them, and his landscapes of Primrose Hill pay homage to Constable. But Whistler? Gainsborough? David? Vermeer?

In fact, the sign of an educated artist is his ability to get something out of other art that has nothing overtly to do with his own; that “something” is the sense of quality, of eloquence and precision within the matrix of a different style, epoch, and idea. The sense of the museum as one’s natural ground—not just a warehouse of motifs to be “appropriated” but rather the house of one’s dead peers from whose unenforceable verdict there is no appeal but with whom endless conversation is possible—this has never left Auerbach, as it never left Giacometti; it hovers behind even the most abrupt and ejaculatory of his works. “When I see the great pictures of the world paraded in my mind’s eye,” he remarked to the art historian Catherine Lampert, one of his more frequent models,

Advertisement

they are great images which don’t leak into other images, they are new things. I could name them, or try to name 20 of them—the Kenwood House Rembrandt is pretty close, the Picasso of the pre-Cubist period called Head (Femme au nez en quart de Brie) seems to me to be one of them. There’s a blue cut-out late Matisse, Acrobats. There’s the Dürer with the bent nose (Conrad Vernell), a Philips Koninck landscape View in Holland. One hopes somehow to make something that has a similar degree of individuality, independence, fullness and perpetual motion to these pictures. But actually one hopes, though of course one won’t achieve it…to surpass them.4

2.

Auerbach was born in Berlin in 1931; his mother, a Lithuanian, had been an art student; his father was a well-to-do patent lawyer. Exiled to England at the age of eight, orphaned by Hitler soon afterward, Auerbach is possessed by filiation, by the mystery surrounding his connections with forebears. He has transposed the wound of parental loss into the realm of art making, and sighted in with awesome concentration—the attentiveness of instinct, rather than of formal art-historical analysis—on how past art might speak to, and through, images made in the present. We do not choose our parents. A painter is drawn to his or her ancestry by a homing impulse that works below “strategy.” In this he is both free and not free. This is not like shopping around for a style to adopt. It is deeper and more compulsive. It is to know one’s heritage, its limits, the challenges these present. Each bloodline entails responsibilities. Auerbach’s is squarely in the “great tradition” of figure painting. He was taught by David Bomberg, who had been the pupil of Walter Richard Sickert, who was the friend and best English interpreter of Degas, whom Ingres begat. He still regards the posed human figure as the ultimate test and unweakening source of a painter’s abilities.

Fifteen years ago this put Auerbach beyond the pale of fashion: he was considered a murky “Jewish expressionist” whose small gnomic renderings of the human figure in abrupt scrawls and pilings of thick pigment were very far from American “postpainterly” abstraction, let alone the iconic brashness of Pop. He was after heavy, sculptural, tactile form, the exact reverse of the “optical” color and agreeable clarity of profile valued in the Sixties, from Kenneth Noland to David Hockney. Moreover, Auerbach was not just unironical—his painting bluntly rejected the possibility of detachment. In the 1960s and into the Seventies irony looked like a fresh approach: a bright, undeceived way of looking at a culture in transition, of feeling out the tingly shudder of the loss of reality occasioned by mass electronic media: “Nothing is real / Nothing to get hung about / Strawberry Fields forever.” The ease with which the times rejected intense feeling, inner states of any sort, did not favor a sympathetic reading of Auerbach’s work.

Today, of course, that innocence has gone and is replaced by something worse—a soured relativism, rising from our media-fixated social environment, that in the name of “irony” derides almost any attempt at deep pictorial authenticity as a trap or an illusion. Irony of that kind is merely the condom of our culture, and it does not help much in understanding an artist whose ambition has always pointed to exacerbation, doggedness, courage, rawness, and the slow formation of his own values. And “newness,” too: the peculiar freshness of unmediated experience.

The idea of newness has intense significance for Auerbach. But it has nothing to do with that exhausted cultural artifact, the idea of the avant-garde. Auerbach’s “newness” means vitality, the seizure of something real from the world and its coding—however imperfect and approximate—in paint. It does not mean a new twist of syntax:

There is no syntax in painting. Anything can happen on the canvas and you can’t foresee it. Paul Valéry used to say that if the idea of poetry hadn’t existed forever, poetry could not be written now. The whole culture is against it because language is always being worn down and debased. But painting is always a fresh language because we don’t use it for anything else. It has no other uses. It isn’t mass persuasion.5

Nor is “newness” a matter of style:

Advertisement

The idiom is the least important thing. If a painting is good enough the idiom falls away with time, and there’s the object, raw and immediate. Think of young Pierre Matisse in The Piano Lesson: a horrible, resentful little boy—knowing, precocious, sly. It’s all there. Or think of Madame Matisse having tea in the garden, the garden furniture, the ceremony of thé á l’anglaise: he couldn’t have done it like Monet, because it wouldn’t have been real. He had to do it new, and make it real.

For Auerbach’s “newness” depends on risks taken, not on stylistic variation:

I do not want them [the works] to be alive, and they don’t come alive to me in ways that are full of clichés or if they seem incomplete or not coherent…. I think the unity of any painter’s work arises from the fact that a person, brought to a desperate situation, will behave in a certain way.

Stress produces constants and these constants are the style. “That’s what real style is: it’s not donning a mantle or having a program, it’s how one behaves in a crisis.”

Newness arises from repetition. It is the unfamiliar found in the midst of the most familiar sight, such as the head of someone you have been painting for twenty years. The element of surprise is

enormously important to me. To do something predicted doesn’t seem to me to be worth doing at all. To do something one hadn’t foreseen—by itself—seems to me to be just a gesture, and I can’t see how that would be interesting. But to have done something both unforeseen and true to a specific fact seems to me to be very exciting.

Auerbach’s work is full of observed facts of posture, gesture, expression, stare, the configuration of the head in all its parts, the tenseness or slump of a body, alertness or boredom, light and shadow: the endless drama of the I and the Other. The brush does not so much “describe” these as go to inquisitorial lengths in finding kinetic and tactile equivalents for them. A dense structure unfolds as you look. The essential subject of the work, however, is not that structure as a given thing, but rather the process of its discovery.

In the late Fifties and through the Sixties the English critics Andrew Forge and David Sylvester wrote about Auerbach with insight and enthusiasm,6 but to most critics his work seemed ill-synchronized with its time. In the late 1960s and early Seventies, as he was moving toward maturity as a painter, his isolation was especially severe; he looked like Pound’s M. Verog:

…out of step with the decade,

Detached from his contemporaries,

Neglected by the young,

Because of these reveries.

Stubbornness exacts its price. In 1986 the critic Stuart Morgan assured the readers of Vogue that Auerbach was “the ultimate pig-headed Englishman.” condemned by his own narcissism to do the same thing over and over again.7 This is a peevish reading, but one can see why such irritations are felt. There are dumb ways of liking any serious painter’s work. In Auerbach’s case the idée reçue is to attach pseudo-moral value to the inordinate thickness of his paint, which is the most obvious feature of his work and threatens it with cliché, as drips do Pollock or dots Seurat. Heavy paint looks worthy; it suggests mucky integrity. As Andrew Forge remarked in 1963, apropos of Auerbach’s thickest and most heavily troweled paintings, “It has been taken—rather insultingly, as a sign of his seriousness, as though it proved he tries hard.”8 But of course thick paint is as much a code as thin, and by this time we should know that neither is more “sincere” or “urgent” than the other. Who was in more travail—Ingres weeping with frustration as he struggled to get right the thin vellum-like bloom on M. Bertin’s sallow cheeks, or some neoexpressionist in the Eighties prolifically turning out his signs for extreme insecurity? If the thickness of Auerbach’s paint does have expressive value, it must arise from some source other than these conventions of sentiment.

To be seen as a peripheral painter, stubbornly holding ground nobody else much wanted in the Sixties and Seventies, excluded Auerbach from what people still called the avant-garde. In the process his work survived the idea of avant-gardeness. Modernist “progress” in art, once an unquestioned faith, seems the merest illusion, now, at the beginning of the Nineties, and there is absolutely no reason to suppose that the apparent “newness” of a work of art generates any kind of aesthetic value. In our fin de siècle we realize what harm this fantasy has done: how it abbreviated aesthetic response and created set menus of novelty for cultural tourists; above all, how it replaced the organic complexities of a serious artist’s relation to the past with a shallow puppet show in which hostility to one’s ancestors mingles with bombastic claims of equality with them.

It takes exceptional historical imagination to reconstruct the boldness and independence of mind of (say) Newton in the act of radically rewriting the laws of nature. In Masaccio, in Michelangelo, in Velázquez or Cézanne the personal heroism and genius is woven into the fabric of the work—also, in the history of art, it becomes clear that as we gain one insight and skill we lose another—we cannot now paint like Bruegel since we do not have the tension of discovery which produce[d] his work. Otherwise—I feel quite close to scientists…the way Kepler arrived at true discoveries on false premises simply by obsessively going over his data seems familiar.9

Art is not like science, though scientific experiment has some of the character of art. Science progresses; art does not. Any third-year medical student knows more about the fabric of the human body than Vesalius, but no one alive today can draw as well as Rubens. In art there are no “advances,” only alterations of meaning, fluctuations of intensity, and quality. The modernist sense of cultural time, fixed on the dictatorial “possibilities” of the historicist moment, is a lie. It has distorted our sense of relation to the living body of art, most of which lies in the past and none in the future, to an absurd degree.

And so in culturally compressing machines like London and, especially, like New York in the twentieth century, obsessed with rapid stylistic turnover (which is what consumer capitalism, in its need to encourage novelty and diversity, made of avant-gardism), Auerbach does indeed look odd. His project as an artist has to do with arresting (just for himself, and for one viewer at a time) the sense of leakage between images which, under the pressure of other media, has been set up as a “postmodernist” value. And seeing one thing well, clearly, and “raw” (a favorite adjective with Auerbach), especially in a way that has no relation to photography and in fact defies everything implied by the rapid glance of pattern recognition we bestow on media images, means seeing it over and over again. “I’m hoping to make a new thing,” he once remarked,

that remains in the mind like a new species of living thing…. The only way I know how…to try and do it, is to start with something I know specifically, so that I have something to cling to beyond aesthetic feelings and my knowledge of other paintings. Ideally one should have more material than one can possibly cope with.10

But the “material” must be concentrated onto one thing at a time.

Both drawing and painting have always been involved here, and Auerbach’s drawings tend to be as ambitious as his paintings. His wish to invest charcoal on paper with the density and “presence” of paint was realized for the first time in a set of large heads begun in 1956. They bear the scars of their making: so much rubbing and erasing that the paper wore through in spots that gave trouble, and had to be patched. They have a disciplined amplitude of form, swift and deep and instinctively drawn toward solidity, as in Head of Gerda Boehm II, 1961 (see page 23). It is the polar opposite of the Cubist fragmentation which, strung on a decorative grid, had become one of the conventions of English art in the mid-Fifties. The charcoal strives to integrate the features, to carry the form around the back of the head, out of sight. “Nothing can be left out,” he would say thirty years later, “but you have to bury the irrelevant in the picture, somehow.”

To do this, he gradually realized, paint would have to relate to drawing in a different way. Auerbach painted inches thick, but this crust of pigment had its peculiar qualities, and was unlike the bas-relief surfaces of Dubuffet and Tapies that had been so much discussed in London in the Fifties. Those were basically sculpture, but Auerbach’s—as David Sylvester put it when reviewing his first show in 1956—“preserved the precious fluidity, the pliancy proper to paint.” When Auerbach’s work failed, as it often did, it was usually because the paint mass was laid over a conventional base of “topographic” drawing—realism with grotesque calluses. He must somehow integrate his growing sense of paint as an “accumulating substance within which the whole world can be experienced” with his need for patient and repetitive scrutiny. The key seemed to be wildness, so that the agenda of the painting stayed open until the last moment of its completion.

Think about the vehemence that goes into some late Matisses—you get a radical reorganization at a very profound level at the very last stages. In a good painting everything is painted with the pressure of a grander agenda behind it, but sometimes the agenda isn’t clear to the artist until the very end. The problem is always to identify it. Then the act of recognizing it can burst the painting, and often it will.

Color alone, he realized, would not do that. His larger problem was to get the paint moving, to modify the sense of arrested time and slow deposit that was built into those interminably reworked surfaces—to give gestural energy to the lump, as in the remarkable Head of E.O.W. V, 1961. (See above.) Without doubt, although Auerbach has been little influenced by American painting, de Knooning’s work was a help here. Auerbach was twenty-seven when he saw Abstract Expressionist paintings for the first time—at the Tate, in 1958. Neither Pollack’s all-over webs nor Rothko’s fuzzy rectangles had the kind of density he admired; de Kooning’s work did. It was clearly based on figure and landscape, and its formal properties—the sense of edge and line, its concern with weight and definition of form, and its figure-ground contrasts—came out of an engagement with the Old Masters and a tradition of studio practice which Auerbach recognized at once. The Dutchman’s hooking, rhythmic line evoked bodies in the jostle of elbowforms and crotch-shapes, and drew them openly in the totemic Women. His paint surface was a membrane, now thick and now a wash, but always under some degree of torsion and tension from the boundaries of the forms. And the linear qualities of de Kooning’s style were embedded in the swiping of the brush; the gesture and the form were one. At the same time there was enough contrast between figure and field in de Kooning’s work to give Auerbach’s figural obsession a handle on it.

In sum, Auerbach found himself admiring in de Kooning what he admired in Soutine—the sort of draftsmanship that is deeply painted, bathes shapes in air and carries the eye around the back of the form, rather than leaving it with the contours and color of a flat patch.

Auerbach’s paintings of his first constant model, Estella West, or E.O.W., had begun, twenty years before, in a spirit of devotional accretion, a slow, obsessed layering. Her replacement after 1963 by the second, Juliet Mills, or J.Y.M., confirmed and accelerated, though it did not directly cause, the freedom and comparative wildness of his mature style, whose main point (apart from a deepened expressive role for color) was to get the whole surface moving under the action of drawing, the decisive linear marks of the brush in liquid paint.

Throughout such work, the sense of mass in movement is what counts. Auerbach was quite specific about that: painting must “awaken a sense of physicality,” transcend its inherent flatness, or fail. This was the opposite of the scheme of academic American criticism in the Sixties and Seventies, whereby modernism was supposed to move in a continuous ecstasy of self-criticism, under the sign of a purified, nondepictive flatness, toward the point where everything not “essential” to it had been purged. Auerbach believed in no such idea of art history, past, present, or to come. Matisse’s découpages were always cited as authority for it, but to Auerbach they meant something quite different:

A late Matisse paper cut-out which seems on the surface, and perhaps to superficial or uninstructed viewers to be a decorative pattern…works because it’s a shape made from a sense of mass, rather than a shape made from a sense of shape, and a disposition made from a sense of infinite space, rather than a disposition on a flat surface. I think there’s a real barrier between the sort of painter who is arranging things on the surface for their own sake and the sort of painter who has a permanent sense of the tangible world.

The sense of mass and of deep space remained as basic to Auerbach’s thinking in the Seventies and Eighties as it had ever been. Perhaps more so; now that the sculptural thickness of the paint was gone, and the space around the subject less congealed and planar, it was the stroke itself that ran forward and backward and around, creating a sense of plasticity and turning. In the process his reliance on stick- and girder-like shapes as drawn scaffolding disappeared, replaced by more fluid drawing. What this indicated was a growing mastery of touch.

There was, certainly, a “signature” in the marks: a preference for hooked closing shapes and Y-shaped open ones, a branching of cranked lines, which grew directly out of the earlier junctures of his drawing. You could not call it a stylistic device: it was more of a natural frequency, the form unconsciously reached for in the act of converting sights to marks. But this fresh continuity of stroke, by clearing more air for improvisation, opened his work to a sort of lyrical imprudence. The dignity of Auerbach’s stoniest portraits of E.O.W. remains, without loss, in the heads he would paint thirty years later. Images like Head of J.Y.M. III, 1980 (at right), seem inviolable in their succinctness and apartness, in the sonority of their dark color, and in the discipline with which impassioned gesture is resolved as structure rather than wasted as surface rhetoric. The difference is that now the order is more complicated. The painter is fishing in deeper waters—a more disturbed flux of appearances, a more declared sense of the frustrations of spatial difference that rise between the painter’s body and the Other’s, frustrations that must somehow be made sense of on the place that lies between: part barrier and part window, the flat white canvas.

3.

Perhaps one should begin where the paintings do, in Frank Auerbach’s studio, a brown cave in northwest London where he has worked for more than thirty years.

It is one of a line of three studios in an alley that runs off a street in Camden Town, a rootedly lower-middle-class neighborhood between Mornington Crescent and the park of Primrose Hill. They were built around 1900, with high north-facing windows. Auerbach “inherited” his studio from his friend Leon Kossoff, in 1954; before Kossoff it had been used by photographers and, earlier, by the painter Frances Hodgkins. The identified artist of Camden Town, up to that time, had of course been Walter Sickert, who kept a studio a couple of hundred yards away, at 6 Mornington Crescent—a narrow three-story terrace house whose stucco façade is as dingy today as it probably was then. The flavor of Camden Town recalls a fact of Sickert’s work that applies to Auerbach’s today—its attachment to the common-and-garden, to the compost of life as it is lived.

You enter the alley through a wicket gate, set between a liver-brick Victorian semidetached villa on the left and on the right a decayed block of Sixties maisonettes. A roughly lettered sign says TO THE STUDIOS. Auerbach’s door opens on a scene of dinginess and clutter. The studio is actually a generoussized room, but it seems constricted at first, all peeling surfaces, blistered paint, spalling plaster, mounds and craters of paint, piles of newspapers and books crammed into rickety shelves, a mirror so frosted with dust that movements reflected inside it are barely decipherable. Because Auerbach paints thick and scrapes off all the time, the floor is encrusted with a deposit of dried paint so deep that it slopes upward several inches, from the wall to the easel. One walks, gingerly, on the remains of innumerable pictures. Where he sets his drawing easel this lava is black from accumulated charcoal dust. “I changed the linoleum three times,” Auerbach says. “The last time quite recently, less than ten years ago. If I didn’t, the paint would be up to here.” He gestures at thigh height. And then, a few days later: “Leonardo said painting is better than sculpture because painters kept clean. How wrong he was!”

The walls are brown, mottled with damp-borne salts. The high north window has not been cleaned in years. It does admit light: on fine May days a tender Rembrandtian gloom, in February a grim Dickensian one. The only color is the paint itself—the canvas on the easel, and two palettes. The first of these is a slab, perhaps wood, perhaps stone, turgid with pigment, inches thick. The second is an extraordinary object, the fossil of a wooden box upended, so that its midway partition acts as a shelf. Warm colors are mixed on the top of the box, cool ones on the shelf. Years of use have turned it into a block of pigment, its sides encrusted with glistening cakes and stalactites of the same magma that encrusts the floor. One side of the box is partly worn through by the slapping of Auerbach’s brushes. The darkness and dirt of the studio are only relieved by the gleam of the paint: cadmium red, cadmium yellow, flake white, pure and buttery in their cans.

Images are pinned on the window wall and above the sink: a photo of Rembrandt’s patriarchal head of an old bearded Jew, Jakob Trip, and another of Saskia; a small self-portrait by Auerbach’s early friend and dealer Helen Lessore; a reproduction of Lucian Freud’s head of Auerbach himself, the forehead bulging from the surface with tremendous, knotted plasticity; a drawing by Dürer of Conrat Verkell’s head seen from below, the features gnarled and squeezed like the flesh structure in one of Auerbach’s portraits; souvenirs of the work of friends (Bacon, Kossoff, Kitaj) and of dead masters. They are all emblems and have been there for years, browned and cockled, like votives of legs and livers hanging in a Greek shrine.

A string runs from above the sink to below the window, carrying a line of yellowed sheets of newspaper, years old. Auerbach hangs his underpants on it to dry. New newspapers will not do, because their ink leaches into the cotton. Paper towels will not do, because (one supposes) they would be too white. Like one of Beckett’s paralyzed heroes, like Sterne’s father in Tristram Shandy, who put up with a squeaking door all his life because he could not summon up the decision to apply a few drops of oil to the hinges, Auerbach is inured to his own domestic irritants. They are part of a solemn game of stasis.

The essence of this place is that things do not change in it. Dust accumulates, waste pigment slowly builds its reef on the floor, the light fluctuates; models (as few as possible, and nearly always the same ones, because Auerbach does not do commissions and not many people can endure the arduous business of posing for him) arrive, pose for three hours, and go; paintings and drawings are finished and are taken away. The studio is an antitype of the Matissean ideal. But it offers the painter a certain stability, a guarantee of changelessness, as Nice did Matisse. “In order to paint my pictures,” Matisse remarked, “I need to remain for several days in the same state of mind, and I do not find this in any atmosphere but that of the Côte d’Azur.” Auerbach’s studio does the same for him. It is a troglodyte’s den of internalization, the refuge in which the artist becomes unavailable, digging back into the solitary habits without which nothing can be imagined, made, or fully seen. There is no television set—“a barbarous invention”—and, of course, no telephone.

The position of each easel is fixed. The wooden chair in which the sitter poses is also fixed, with a white circle drawn on the floor around each leg. To the left of the chair is a pedestal paraffin heater, unlit, on which the sitter balances a cup of strong coffee and an ashtray. To the right is another heater, mercifully red-hot in winter, with another locating circle of white paint drawn around its base. You know you may not move it, and do not try to. You roast on one side and freeze on the other. The distance between Auerbach’s surface and the sitter’s face is always the same. The sitter has only one way to sit: facing the easel, staring back at the stare. Whatever happens to left or right is not part of a room; it is just “space.” The purple cover on the studio bed has its own role in the light, as the sitter will find when, coming in from the underground station at seven-thirty one winter morning, he throws his Times on it; after twenty minutes’ work Auerbach screws up his face and complains about the nagging white light reflected from the paper. This morning in February 1986 there are other irritations. The outside lavatory has frozen and the ice in the bowl has to be broken with jabs of a broom handle. Inside the studio, a plastic jug of turpentine has cracked in the cold and flooded the floor under the sink.

The work of drawing begins. Auerbach has a sheet of paper, or rather two sheets glued together, ready on the easel. The paper is a stout rag, almost as thick as elephant hide, resistant to the incessant rubbing out that will go on for days and weeks. As he scribbles and saws at the paper the sticks of willow charcoal snap; they make cracking sounds like a tooth breaking on a bone. When he scrubs the paper with a rag clouds of black dust fly. An hour into the session the sitter blows his nose and finds his snot is black. The studio is like a colliery; the drawing easel is black and exquisitely glossy from years of carbon dust mixed with hand grease. Auerbach works on the balls of his feet, balanced like a welterweight boxer, darting in and out. Sometimes he and the sitter talk. He recites from memory long runs of Yeats, George Barker, and Auden. Asked if he ever works to music, he answers with a curious vehemence: “Oh, no, never! I like silence! I think I must be completely unmusical. I can’t remember phrases; that makes me useless in a concert hall. If you’re to enjoy music I suppose you have to remember something of what went before in order to grasp what you’re hearing at the moment—and I can’t. That rubbish of Pater’s! It is absolutely untrue that art aspires to the condition of music. Painting never wants to be like music. It is best when it is least like music: fixed, concrete, immediate, and resistant to time.”

Then he shuts up and goes into high gear, working with redoubled concentration, cocking his head at the sitter and grimacing. He hisses and puffs. He darts back to consult the reflection of the drawing in a mirror on the wall; the sitter sees Auerbach’s peering reflection, the chin and cheeks smutched with black. Sometimes his mouth broadens into a rictus of anxiety, very much like a Japanese armor mask. He talks to himself. “Now what feels specially untrue?” “Yes, yes.” “That’s it.” “Come on, come on!” And a long-drawn-out, morose “No-o-o.” Now and again he fumbles out a book from the nearby shelf, opens it to a reproduction—Giacometti’s Woman with Her Throat Cut; Cézanne’s Self-portrait with Cap, 1873–1875, from the Hermitage; Vermeer’s young turbaned girl—and lays it on the floor where he can see it, “to have something good to look at,” a purpose not kind to the sitter’s vanity until one understands that Auerbach is hoping for osmosis.

By the end of the day the drawing is some kind of a likeness, though not a flattering one: a blackened Irishman with a squashed nose and a thick, swinging chop of shadow under his right cheekbone. Through the next twelve sittings, spaced over not quite four weeks, this creature will mutate, becoming dense and troll-like one day and dissolving in furioso passages of hatching the next; lost in thought in one version, belligerently staring in another, eye contact almost obliterated in a third as the mass of the face is lost in a welter of hooking lines (the hair) and zigzag white scribbles of the eraser (a twisting in the space behind the head). (The drawing appears on the next page.) In the end, the likeness is retrieved, but as a ghost, the color of very tarnished silver.

4.

Auerbach remembers few details of his Berlin infancy and childhood. His main memory—probably a common one for many German-Jewish children in those bad years—is of a pall of parental strain and worry that seemed to lie across everything he did. The year Frank Auerbach was born, 1931, was also the year the Austrian Credit-Anstalt Bank collapsed, sending fiscal shudders through Central Europe; within months the closure of the German Danatbank had led to the temporary shutdown of the whole German banking system. The SA brownshirts were marching in the Berlin streets when Auerbach was learning to toddle. When he was two, Hitler became chancellor and, through an Enabling Law, dictator of Germany; the boycott of Jews began, and the first concentration camps were set up.

People like Auerbach’s parents, the liberal, educated German Jews of the professional classes, could not imagine the Final Solution. But the Auerbachs, like the parents of another Berlin Jew who years later was to become one of their son’s few intimates in London, the painter Lucian Freud, lived in growing anxiety. The fear of giving offense to the majority culture of German gentiles was bred into every assimilated, middleclass Jewish boy in Berlin, to a degree inconceivable in a Polish stetl. It seems to have hung over the Auerbachs’ domestic life, which was not altogether happy in any case. With their son it came out in what Frank Auerbach remember as “frantic coddling.” “I remember velvet knickerbocker suits and no freedom. I couldn’t run in the park near the house. I couldn’t step outside the door on my own, of course; and my mother would begin to worry if my father was half an hour late home.” The little boy could not make sense of this. He accepted the protection he needed but balked at the rest, translating it, in adulthood, into “a profound impatience with the self-protective life of the bourgeoisie.”

By 1937 it was clear that the six-year-old boy was going to be in real danger if he stayed in Germany. But his father would not go; presumably, like many other Jews, he hoped that Nazism would soften, and that resolute adults might still breathe the air that would choke a little boy. Frank Auerbach was saved by chance and luck. In 1937 the partner of one of his lawyer uncles had gone to Italy, and in Tuscany he met the writer Iris Origo, the future author of The Merchant of Prato, her now-classic study of the quattrocento Florentine wool trade based on the archive of the Pratese burgher Francesco Datini. Princess Origo had begun to worry about the impending fate of Jewish children in the Reich, and she decided to do something practical about it, however small: better one act of real charity than any amount of talk. She agreed to put up the money for the keep and education of six boys and girls if they were sent to safe haven in an English school. None of the children was personally known to her. One was Frank Auerbach. It took time to make the arrangements; more time, almost, than the family had. In the early spring of 1939 the Auerbachs packed their son’s bag, took the train to Hamburg, and put him on a ship to England. It sailed on April 4, just before his eighth birthday.

Auerbach never saw his parents again. During the next three years, a few “Red Cross” letters—postcard messages restricted to twenty-five words, which gave no real news except the indication that Max and Charlotte Auerbach were still alive—found their way to him in England. But after 1942 there was nothing. The ovens had swallowed them. Soon after the end of the war, one of Auerbach’s friends recalls, he received a package containing some of his father’s effects, including a gold watch. He took it to a jeweler’s, sold it, and used the money to buy another watch. Years would pass before he would speak of his parents to anyone.

Can one speculate about how, if at all, this catastrophic loss might have borne on Auerbach’s work? “It is, or it is not, according to the nature of men,” wrote Thomas de Quincey, parentless himself, “an advantage to be orphaned at an early age.” Every year, millions of children are torn from parental security, cast bereaved into the world, orphaned for reasons they cannot grasp and will unconsciously misinterpret for the rest of their lives; among them, some tiny fraction of a percentage grow up to be painters or sculptors. The idea that there is some necessary or predictable connection between the loss of one’s parents and the shaped concerns of one’s work as an adult (as though a common trauma inscribed itself in a common style) is clearly absurd. That Auerbach in boyhood must have instinctively construed his own exile and his parents’ death as their abandonment of him is likely, indeed certain; from the watch story, one can deduce a yearning aggression against the absent father.

But early parental loss can be the most powerful of creative goads. We patch together structures, solid or rickety, to fill the emotional void, and invest them with a degree of healing power. The future artist or intellectual, having suffered in full measure as a child the lovelessness, abandonment, and terror of one’s own death which are the inseparable consequences of the death of one’s parents, may indeed find creative risk more tolerable because of the feeling of power and self-sufficiency that its successful outcome gives: an early loss may (or as de Quincey reminds us, may not) favor later leaps in the dark. At the same time the hunger for security may inscribe itself in the child’s adult habits, and this may perhaps cast some light on Auerbach’s singularly fixed and stable rituals: the daily routine of work, work, and more work, early morning to dusk; the unchanging studio, embalmed in waste paint, guarded by unaltering scraps and emblems; the long construction and daily erasure and unpicking of the image, like Penelope’s weaving; the doggedness of repeated attack on a familiar motif which is the peculiar mark of Auerbach’s temperament. The deep family intimacy denied to him in boyhood is summoned and reenacted in his work, in his hourly transactions with the object of scrutiny. “To paint the same head over and over,” he will say, “leads you to its unfamiliarity; eventually you get near the raw truth about it, just as people only blurt out the raw truth in the middle of a family quarrel.”

In a more general way, Auerbach’s work is quite free of the displaced Oedipal struggle—the desire to murder the paternal tradition, whether framed in Futurist manifestoes or soixante-huitard calls to radical cultural renewal—which was such a feature of avant-garde mythology in his youth. He derides “artists who produce a smooth series of radical-looking changes but no upheaval at all.” On one hand, Auerbach would seek forms from which a full sense of “reality” could be unpacked—the structure, weight, density, malleability, and resistance of the object, the stare of a head in the studio, the sag and sheen of a nude’s belly, the bustling sky over a zigzag tree in Primrose Hill.

But at the same time, every one of his paintings, the failures as well as the successes, is imprinted with the desire to engage on levels deeper than mere quotation with the great tradition of Western figurative art, a tradition mangled and weakened almost beyond recognition in the last half of the twentieth century. He is, in short, a conservative artist. The tension between radical will and conservatism gives Auerbach’s work, as it gave Giacometti’s, much of its peculiar intensity. It may well be that the emotional roots of his convictions about the nurturing past which pervade Auerbach’s art wind back, however tenuously, to the eight-year-old boy who came down the gangway of the ship from Hamburg on April 7, 1939, and found himself with two newly made shipboard friends and their nursemaid on the dock at South-hampton, clutching a suitcase, ready to start learning in a strange country.

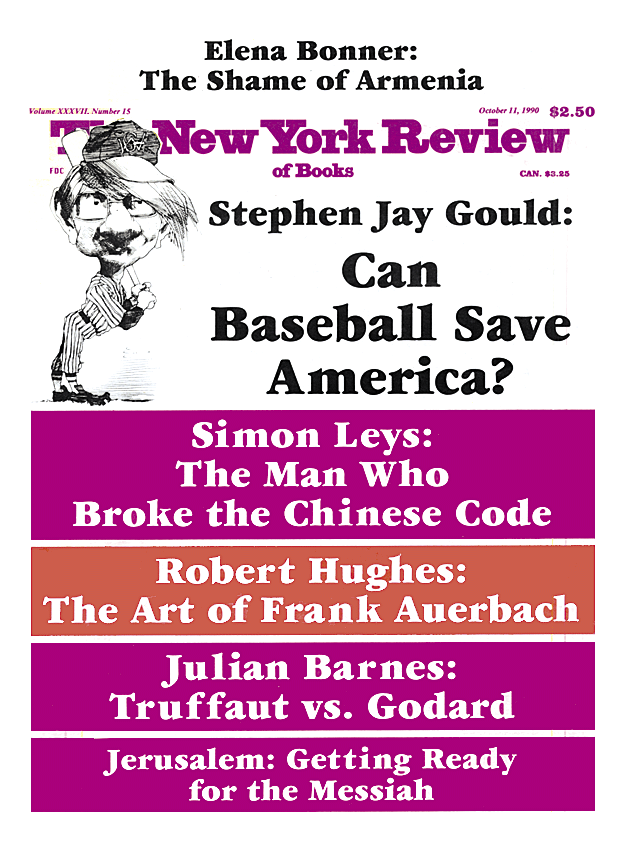

This Issue

October 11, 1990

-

1

Catherine Lampert, “A Conversation with Frank Auerbach,” interview in exhibition catalog of Frank Auerbach (London: Hayward Gallery, 1978), p.22. ↩

-

2

March 3, 1971. ↩

-

3

Lampert, “A Conversation,” p. 22. ↩

-

4

Lampert, “A Conversation,” p. 10. The correct title of the Dürer is Contrat Verkell. ↩

-

5

Unless otherwise indicated, quotations are taken from conversations with the artist recorded between February 1986 and January 1987. ↩

-

6

See especially David Sylvester, “Young English Painting,” The Listener (January 12, 1956): “Auerbach has given us, at the age of twenty-four the most exciting and impressive one-man show by an English painter since Francis Bacon’s in 1949 . These paintings reveal the qualities that make for greatness in a painter—fearlessness; a profound originality; a total absorption in what obsesses him; and above all, a certain authority and gravity in his forms and colours.” ↩

-

7

Stuart Morgan, Vogue (London: May 1986). ↩

-

8

Andrew Forge, “Auerbach and Paolozzi,” The New Statesman (September 13, 1963). ↩

-

9

Frank Auerbach, letter to Robert Hughes, August 1, 1988. ↩

-

10

Lampert, “A Conversation,” p. 10. ↩