June 8, New York. “Mozart: ‘Prodigy of Nature,’ ” the exhibition at the Morgan Library, is a humbling experience. Some fifty Mozart manuscripts are displayed (and one Beethoven, a copy of Mozart’s Quartet KV 387) ranging from four pieces composed at age five to a draft page of the Requiem; fourteen autograph letters, early and late; and programs and documents, including Mozart’s marriage contract. John Russell’s polished report in The Times begins by remarking that “great music falls from the air” and “in almost every case the autograph manuscript of that music is right there beneath our noses…. The thing heard and the thing seen are one.”

Yes. But we cannot turn the pages, and when one of the Queen of Night’s arias fell from the air while I was studying a sketch for the Priests’ March, I could only stop, not look, and listen, being unable to read one score while the attention of the ear was monopolized by another. The nonstop recorded concert does feature performances of the manuscripts on display, however, and after two or three visits, and on an uncrowded morning, the visitor would probably be able to chase from one showcase to another in time to glimpse the first few measures of whichever concerto, symphony, sonata, aria, or quartet has come up on the tape.

Mozart’s manuscripts are neat. Johann Anton André, who purchased the bulk of them from Mozart’s widow in 1799, remarked that the notes are “small, fully shaped and show no signs of hesitation.” But to follow them during performances, now possible in several facsimiles, is an acquired skill. The lack of vertical alignment, the long note or long rest placed in the middle, instead of, as today, at the beginning of the bar, is an impediment. Another is that musicians have become accustomed to reading Mozart’s appoggiaturas in written-out form. The Morgan exhibition is for the musically literate.

And for those who read German. Only a few passages from the letters on display have been translated, and none of the marginalia. One of Mozart’s scatological letters to his cousin Maria Anna Thekla Mozart is left entirely in German over a caption describing the contents as “vulgar to the point of being unprintable.” Dear me! Do musicologists not read contemporary fiction and not go to the movies? Nor is the catalog’s sniffy dismissal of the “Bäsle” letters (Maria Anna’s nickname) as “notorious” any help. Freud found them perfectly normal.

Twelve of the autograph scores are of symphonies, twenty-one are of music for small chamber-music combinations—quintets, quartets, trios, duos—and twelve are of keyboard works, including the Preambulae and the great A minor Sonata. Only four operas are represented, the Magic Flute as aforesaid, the Impresario by the complete full score, Tito by the Act I duettino, Figaro by the draft of an aria and an arrangement of another, “Non so più cosa son,” for violin and piano.

Otherwise the most important treasures in the display cases are the thematic catalog, the Verzeichnüss aller meine Werke, that Mozart kept from 1784 to 1791, and the 300-page Thomas Attwood manuscript, the record of this English pupil’s lessons with the composer, twelve pages of it in Mozart’s hand, and 115 in his and Attwood’s. One of the disappointments of the bicentenary of the composer’s death is that the Attwood volume has not appeared in facsimile, along with a book on what is known about him and Mozart’s other, particularly female, pupils, the gifted Barbara Ployer, the beautiful Magdalena Hofdomel, Josepha Auernhammer (who fell in love with him), the mysterious Frau Schulz (pianist and composer), the fifteen-year-old Thérèse Pierron (the harpist daughter of the flutist Count de Guines, wrongly “Duke” in the Morgan catalog), Countess Thiennes de Rumbeke, Countess Khevenhüller-Metsch, the eighteen-year-old Thérèse von Trattner, for whom he wrote the Sonata KV 457, Marianne Willman, and Rosa Cannabich, for whom he wrote the Sonata KV 309.

The exhibition catalog invites some quibbles. The Prague Symphony is not in the key of “E flat.” And if Mozart’s net annual income for the last eight years of his life was $28,000 in 1990 dollars, he can hardly be said to have been “extremely” well paid. A map entitled “Europe in Mozart’s time,” evidently intended to trace the extent of his travels—Scandinavia and the Iberian and Greek peninsulas not being included—oddly omits many of the cities in which he performed, such as Dresden and Leipzig, while locating some in which he did not. Odder still is a reference to Don Giovanni and the “polymetric preparation for the ball. (The great Sextet in Act II also bears memorable witness to Mozart’s musico-dramatic genius.)” But the music is polymetric, not the preparation for the ball, and the parenthetical non sequitur makes one wonder which pieces in Don Giovanni do not bear witness to the same.

Advertisement

More serious is the catalog’s assurance that “Mozart’s legacy, unlike Bach’s, would be little diminished had he never composed a note for the Church.” The legacy would be sadly diminished by the loss of the Ave verum corpus and of the most popular of Mozart’s early pieces, the Exultate Jubilate with the “Alleluia,” and profoundly diminished by the disappearance of the “Qui tollis peccata mundi” from the C-minor Mass, an isolated peak but different in kind from any of the composer’s other creations, a work without successor, like the Concerto KV 271 and the Sinfonia concertante, and like them a look into undeveloped dimensions of Mozart’s creative universe. But then, I would place this harmonic and contrapuntal masterpiece above any other opus of the same length.

The thematic catalog is open to only one page, of course, but the beautiful new facsimile of it, introduced and transcribed by Albi Rosenthal and Alan Tyson1 , is available in an adjoining room. Rosenthal’s history of the volume brings Mozart to life in two glimpses of him taken from A.H. André’s not-yet-translated Zur Geschichte der Familie André.2 The author’s ancestor, Johann Andre, head of a publishing firm in Offenbach and father of the Johann Anton André mentioned above, received a visit from Mozart during the composer’s 1790 stay (September 28–October 15) in nearby Frankfurt:

Clad in a grey travel coat with short collar, Mozart stopped in front of the André house. No sooner had he alighted from the coach than he was attracted by the dance music: the male and female workers of the firm had been given permission to hold a dance. Mozart mixed with them quickly, chose the prettiest girl and danced with her for a long time to his heart’s content.

(This Offenbach excursion is not recorded in English-language biographies of Mozart; perhaps the lost letter sent to his wife from Mainz, October 17, refers to it.) In Mannheim, on October 23, Johann Anton André, aged fifteen, attended a rehearsal for Figaro (wrongly Don Giovanni in Rosenthal) during which “Mozart complained about Kapellmeister Fränzl’s slow tempi and asked for livelier ones.” (Ignaz Fränzl’s brother Friedrich married Johann Anton’s sister.) On this occasion Johann Anton described Mozart as “a small, nervous man of rather pallid complexion, but with reddish cheeks and a large prominent nose.”

In 1805, Johann Anton André published the Verzeichnüss, according to some sources the first book produced by the lithographic process. A facsimile appeared in Vienna in 1938, in an edition of only two hundred, and was reissued in New York in 1956. But the Rosenthal-Tyson book is the first to reproduce the final fourteen pages, ruled with five pairs of staves like the preceding twenty-nine, indicating that Mozart expected to live longer and to continue to compose, but unlike them, without musical incipits. The empty staves are almost unbearably poignant.

Again and again the reader marvels at the dates of the entries, above all of the E flat Symphony on June 26, 1788, of the G minor Symphony on July 25, and of the Jupiter Symphony on August 10, with six smaller works appearing between the first two. How can even the greatest thinking-feeling intelligence produce three immortal masterpieces, each so utterly different, at such speed and without the slightest slip? Not believing in thaumaturgy, we turn to Wordsworth’s poem about the human mind being “of substance and of fabric more divine” than the world of nature. Six works fully described by the composer in the Verzeichnüss have been lost while, from oversight or other reasons, twenty that are not included survive.

June 11, Vienna. The whole city is selling, living on, excusing itself through, Mozart. What passes for his likeness is everywhere, most often in the Barbara Krafft portrait (painted twenty-seven years after his death): on walls and kiosks, streetcars and buses, T-shirts and embroideries, posters and postcards, plates and placemats, calendars, candy boxes, shopping bags, baubles and souvenirs of every kind, and subliminally in television commercials. The music stores advertise “the complete works” in 180 compact discs, the bookstores display dozens of new titles (including important ones on Mozart’s widow and sister and the still insufficiently explored contents of their correspondence after his death). Austrian Airlines passengers receive free Mozart CDs, and Vienna hotel guests find a Mozart wrapper on the traditional bedtime chocolate mint on the turned-down duvet.

Tourists are herded to the sites of Mozart’s residences, and from church to church (the St. Stephen of his marriage and funeral and the St. Marx of his first Mass, conducted, aged twelve, in the presence of Empress Maria Theresa), from cemetery to cemetery (the one with a monument to him, where he isn’t buried, to the one in which he is but nobody knows where). They go afterward to the Café Mozart and the Mozart Bar, or to hear the Mozart Sängerknaben, or to see the “Wiener Mozart Konzert”—the orchestra and other performers wearing eighteenth-century costumes and wigs—or to the Mozart opera in one of several theaters.

Advertisement

All-Mozart programs are also pandemic, and pernicious, thanks to too many minuets, major keys, obligatory repeats, perfect cadences, out-of-style and banal cadenzas, and too much merely well-made music (like the Haffner Serenade and that very long opera La Finta Giardiniera, which keeps promising to take off but does not). None of the programs offers even a touch of experiment, such as performing the A major Violin Concerto with the less good second version of the slow movement alongside the marvelous first one that Brunetti, the Salzburg violinist, rejected as “artificial,” meaning that he could not play it.

The Mozart Ausstellung in the Künstlerhaus, presented by the Historisches Museums der Stadt Wien, is a huge, labyrinthine affair for only the most enterprising Mozartians, and the catalog, Zaubertöne, Mozart in Wien 1781-1791, is too heavy to schlep even for them; yet as many of its 614 pages as I have worked through so far contain information I have encountered nowhere else. (Did you know that the score of the Six German Dances KV 571 had been in the possession of the Emperor Maximilian of Mexico and was kept in Schloss Miramar near Trieste until October 1927?)

The walls just inside the entrance are covered with maps that chart all eighteen of Mozart’s journeys, distinguishing them by varicolored lines. As in New York, a perpetual Mozart concert is piped in, but the volume is lower and in the furthermost rooms mercifully faint. Fewer autograph scores (about thirty, including the G minor Symphony, the D minor Concerto, and part of the second act of Così fan tutte) are shown than in New York, but many more autograph letters. Dioramas and other exhibits present aspects of Viennese life in the 1780s with which Mozart would have been familiar. At any rate, he must have known the same kinds of beds, chamberpots, furniture, kitchen utensils, and table wares, and did know similar billiard tables. Mannequins dressed in the costumes of the period confirm that his Viennese contemporaries were a smaller race than ours (and he himself, as noted in every description, was unusually small among them).

The sciences are represented by pictures and reproductions of some of the actual machinery of Volta’s and Galvani’s experiments in electricity; by drawings of Linnaeus’s botanical and histological work; by displays indicating the state of contemporary knowledge in anatomy, optics, chemistry, and medicine, this last terrifying in the case of clysters that injected tobacco-smoke, and surgical instruments—for phlebotomy, scarifying, and obstetrics (“Geburtshilfe“)—less so in the pills, powders, and sticking plasters of the typical traveler’s pharmacy. Mozart’s friend Mesmer has more than one exhibit to himself, though no parallel is drawn between his and Freud’s studies in hysteria and their respective uses of magnetism and hypnosis.

The catalog essay on Mozart’s literary world, illustrated by books, a hand press, and writing materials, emphasizes the Aufklärung (Enlightenment) philosophy of the time and argues convincingly that Mozart’s April 4, 1787, letter to his father on death derives in part from Moses Mendelssohn’s Phädon: The Immortality of the Soul. Mozart’s library, which included this volume as well as the works of Ovid, Wieland, Molière, and Metastasio, is exhibited here in the editions that he owned, and in at least one case by his own copy.

During the overture to Cosí fan tutte at the Volksoper, the “philosopher” Don Alfonso emerges from the orchestra pit, crosses to a puppet theater at the side of the stage, manipulates the figures inside to positions opposite those in which he had found them, takes pen and paper and makes notes, all much to his amusement. But not to mine, in this or any of the other distracting and tiresome stage business. I would prefer a tacky backdrop of Naples and Vesuvius to the nondescript panels on the revolving, merry-go-round set, which, incidentally, creates the wrong kind of tension: Will the actors get on or off the treadmill in time? The chorus, ghostly in white clothes and white masks, is, as should be, not involved in the action. The sex is explicit as the couples “wife”-swap on stage-front beds, but this overemphasizes the unresolvable structure of the plot: clearly the new partners are better matched than the old and to return to the past would be disastrous. Mozart’s sympathies, the music tells us, are with the women (the sisters).

I am undergoing one of my seasonal changes of mind about Così. The equations are too pat, though Mozart quickly distinguishes the personalities in his symmetrical pairs. Then, too, Despina’s insolence is too far below the level of Figaro’s, the Don is a cutout, and the long-forseen conclusion is too slow in coming.

In contrast, The Magic Flute, by the Hamburg Opera at the Theater an der Wien, is a torture. The prompter, wearing a stuffed-parrot hat, is in full view throughout, the serpent sports a bare, human, but larger-than-life bottom, the Sarastro is feeble when he should be stentorian, and the Queen of Night is a screech owl. How I regret having missed Jonathan Miller’s Figaro at the Vienna State Opera last month, reliably reported as the most intelligent and successful staging ever.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum’s auditory exhibition Die Klangwelt Mozarts is a revelation. We go through wearing earphones and hearing tapes of the old instruments on display, each played alone, in demonstration, then in ensembles, and, for comparison, in juxtaposition to tapes of the modern versions of the same instruments. The result is a triumph for the “original instrument” lobby.

The largest collections are of the string family—an Amati violin with white frets, thought to have belonged to Mozart’s father—and keyboard instruments, organs, clavichords (first mentioned in Austria in 1407, according to the voluminous catalog), pianos (including a replica of the small one that accompanied Mozart on his travels), glockenspiels. The winds include eight sizes of block flute, curved oboes, English horns bent like bows, bassoons, serpents, basset horns (Rube Goldberg contraptions with metal braces like steam engines or automobile horns, c. 1905), small-bell trombones, and several sizes of trumpets, with their wooden mutes. The percussion section includes cupboardlike sets of musical glasses, cymbals, triangles, tambourines, side and bass drums, and timpani both large (bombinating) and small (which, playing a quiet tremolo, could be said to sound humdrum). The most beautiful instruments are lutes and mandolins, zithers and pedal harps, but the curiosity of the exhibition is the glass harmonica, invented by our own Benjamin Franklin: Mozart (MOZART!) had a musical debt to America.

The “Mozart Requiem” exhibition in the Austrian National Library—still another large catalog—is padded with uninteresting Requiems by precursors and successors. But the score-book of Mozart’s is opened, movingly, to the Lacrimosa, the last page in his hand.

In the street by the entrance, a flute-playing panhandler is blowing the accursed Nachtmusik, but I refrain from stopping my ears and instead give him schillings. After all, Mozart worship is not the worst religion the world has suffered.

This Issue

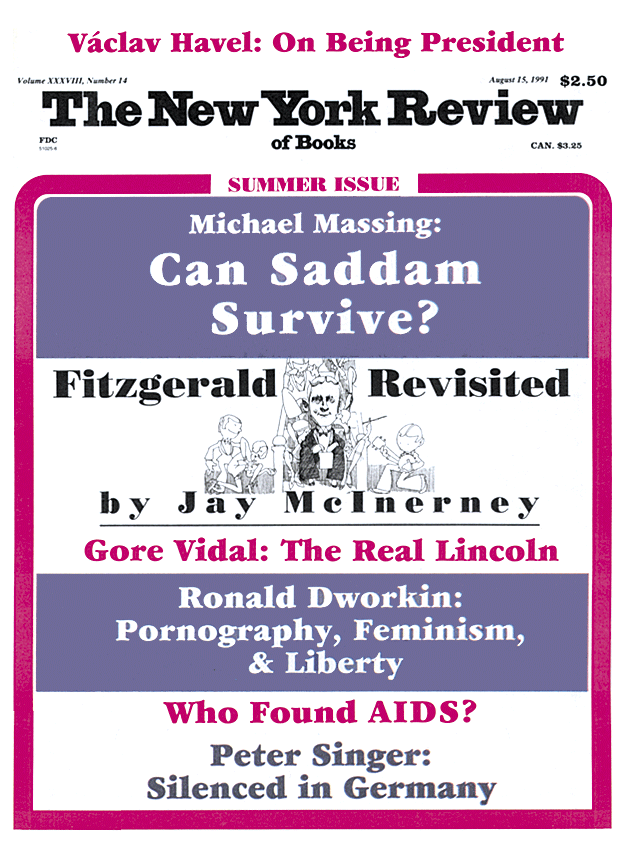

August 15, 1991