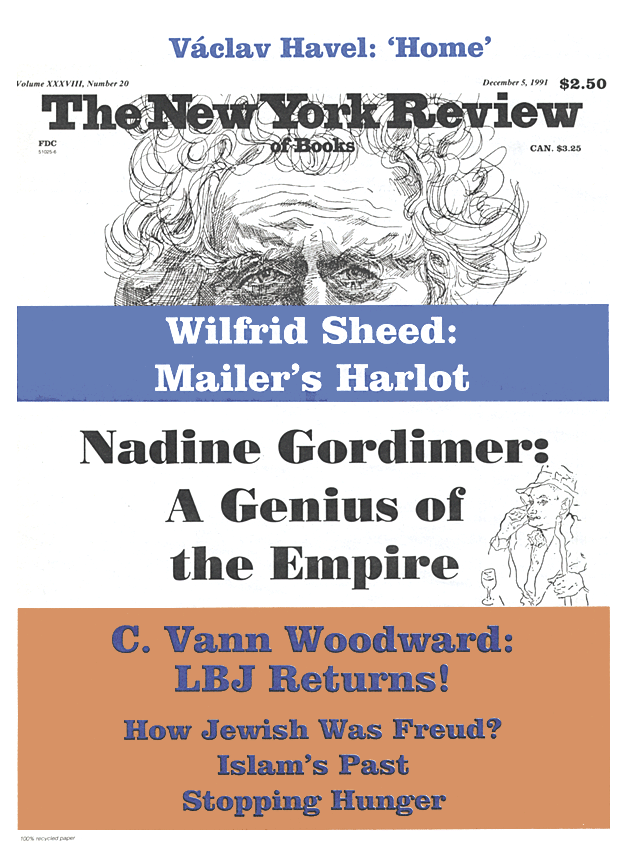

Among the presidents from Franklin Roosevelt to George Bush, Lyndon Johnson has no serious rival for the distinction of being held in lowest esteem in current public opinion. A recent Harris poll found him ranked at the bottom of nearly all categories named. These included high moral standards, in which even Richard Nixon placed above Johnson, and John F. Kennedy stood at the very top. There seems little doubt that LBJ is the president Americans now most love to hate.

No simple explanation would serve to account for this, but any attempt that neglected certain complexities would surely fail. Outstanding among them are those of the Vietnam War. What with conservatives blaming Johnson for losing it, liberals blaming him for fighting it, and Americans generally seeking some villain on whom to unload their burden of shame and guilt and unable to use a martyred Kennedy for that purpose, what better scapegoat could they find? And he a southerner who had shattered the Yankee myth of invincibility and subjected true-blue Americans to their first admittedly lost war. And further, how could so crass a southerner be permitted his claims to have done more for civil rights and blacks than any president since Lincoln, and to have gone on to score more humanitarian reforms with his War on Poverty and his Great Society program than all of them put together?

A public need has grown for evidence that would justify an ever more derogatory image of LBJ. This need has been served mainly by journalists of varied talents and methods with books of several degrees of fairness and balance or lack of both. The latest, longest, and most ambitious of these is a multivolumed work in progress by Robert A. Caro that only gets him to the Senate in its second large volume. Caro lays great stress on digging up facts, with special attention to those that support his thesis. The fairness and balance and sense of humor with which he uses his vast store of facts have been questioned by a reviewer in these pages who called his book “the inverse of gilding the lily.”1

In contrast to the attention historians have lavished upon his predecessors and successors in the White House, scholars have shied away from Johnson. No serious, full-scale biography by a qualified historian has come forth until the appearance of the recent book by Robert Dallek. Known best for his Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, and the author of several other books, Dallek plans two large volumes on Johnson of which Lone Star Rising: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1908–1960 is the first.

But how can anyone, however scholarly, pretend complete impartiality and detachment about a subject like Lyndon Johnson? Professor Dallek does his best to avoid partisanship, polemics, and thesis riding, and he attempts to deal fairly and fully with all sides. While he has gone so far, in a statement to the press, as to place LBJ along with FDR as “one of the two most brilliant American politicians of the 20th century,” he fills in the unsavory side of the story as well—ballot-box stuffing, law flouting, court manipulating, and the skulduggery of bullying and bribing. Politics, for Johnson, was giving and taking. That was the game as he learned it, only he played it harder and played it for keeps. Principles and noble causes were for the statesman he aspired to become, but one had to be elected and stay in office to become a statesman. Meantime ideals and causes could wait—except when they became useful from time to time.

For every quality offered to characterize the man by one acquaintance, its opposite was put forth by another. His principal aide for a time, George Reedy, called him a Jekyll and Hyde personality, “a man of too many paradoxes,” “magnificent, inspiring” one minute, “an insufferable bastard” the next. In Dallek’s words, “Lyndon was a paradox: driven, grating, self-serving on one hand; warm, enjoyable, giving on the other.” To reconcile the opposites: “in return for the attention, influence, and power he craved and aggressively pursued, he gave concern, friendship, and benevolent support.” For every complaint of his greed, vindictiveness, and offensiveness, one can find testimony to his generosity, magnanimity, charm, and humor.

Wherever he was and in whatever circumstances, LBJ needed to be the best and have the most. He had to be the center of attention, no matter what the cost. His height of six feet three and a half inches helped, but he would resort to anything needed, including his considerable gifts of mimicry, and an endless stock of anecdotes. In a pinch he was capable of setting off his alarm clock watch. Even his exhibitionism has been called, by some of the people asked by Dallek, another paradox—the cover for an alleged shyness and insecurity.

Advertisement

Work was an obsessive compulsion, “as essential to him as breathing,” and he “an addict who needed a regular fix.” He was at it by 6:30 AM and kept at it until the small morning hours. He dictated, read, and signed as many as 250 letters a day, chain-smoked some three packs a day, developed a bleeding rash between his fingers, and signed letters with his hand wrapped in a towel to keep blood from staining the paper. Everything was work, all work politics, and everything had to be done now. He imposed his relentless personal regimen on all who worked for him. “They worked at a breakneck pace—days, evenings, nights, often seven days a week, week after week.” And when they lagged or erred he “chewed them out” publicly and ruthlessly. Crackups and breakdowns occurred in the Johnson staff. Yet they usually came back for more with remarkable loyalty, often with professions of devotion.

In his private life, what there was of it, some of the same characteristics and compulsions were manifest. He asked Lady Bird to marry him the day he met her. She was repelled and attracted at the same time, but soon yielded to what she described as the “whirlwind.” It was not an untroubled union, but they complemented each other’s personality traits and ambitions and worked together well. One of Lady Bird’s troubles was Lyndon’s womanizing and “compulsive need for conquests.” For a time, Dallek writes, he had “what amounted to a harem.” When John Kennedy’s activity of the sort was mentioned, Lyndon would declare that he “had more women by accident than Kennedy had on purpose.”

Origins, ancestry, parents, and childhood, essentials for understanding this seeming monster, are not neglected by Dallek. Was Lyndon the son of impoverished subsistence farmers or the descendant of prominent southern families? He was something of both. At least there was some substance to his claim that among his ancestors were congressmen (two), college presidents (one), and governors (one), “when the Kennedys in this country were still tending bar.” Lyndon came of the fourth generation of Texas Johnsons, the first two of which had seen better times. His grandfather, Sam Johnson, joined the Texas Populist Party, and his father called himself “a latter-day Populist.” Sam Jr. believed politics was a struggle between democracy and corporate power and won election to the state legislature, one of the last members “who still wore a gun and looked like a cowboy.” Lyndon admired his father, followed him everywhere in campaigns and rallies, and watched proceedings for hours from the Statehouse gallery as a boy.

His mother, Rebekah Baines Johnson, whose grandfather was the college president on Lyndon’s family tree, did all she could to foster his conviction of his birthright to prominence. When her father died in 1906 it was his seat in the legislature Sam Johnson won and his daughter Sam married. Rebekah was not only born to the political life but she had a college education and aspirations for finer things. She gave this up for a life of drudgery in a log house in the hill country west of Austin without plumbing or electricity. When Lyndon was five and farming proved a failure they moved to Johnson City, a desolate village of 325 souls, no pavement, no trains, still no plumbing or power, and “almost nothing to do or any place to go.” Things got worse when Sam fell sick of an undefined illness, gave up his seat in the legislature, and went into debt. With no income, the impoverished family then began to live “from hand to mouth,” partly on charity, and fell deeper in debt. The best Sam could do at forty-six was to get a job as a part-time game warden at two dollars a day.

Lyndon’s response to this troubled and insecure childhood was an explosive mixture of rebellion, defiance, and arrogance. He was uncontrollable at home and in school, unwilling to submit to authority, and determined to bend siblings and classmates, even teachers and parents, to his will. With its bewildering and contradictory expectations of achievement and prominence and its realities of poverty and failure, his unhappy childhood dogged Lyndon Johnson all his days. He managed to get a degree at Southwest Texas State Teachers College, a “third class” institution with course requirements “closer to those of a high school than a college.” With no money from home, he did it on small loans and campus jobs, first collecting trash at $8 a month, later working as assistant janitor at $12, and finally as errand boy at $15. With the cheapest meal contract at $16 a month for two meals a day, he sometimes went hungry.

Johnson’s more important education was the on-the-job self-training he got from taking complete charge of the Washington office of a freshman congressman from South Texas in 1931. Richard Kleberg was a multimillionaire playboy devoted to horses, golf, and polo, and largely an absentee congressman. He cheerfully left the humdrum grind of office duties and the demands of constituents in the hands of the wholly green twenty-three-year-old youth he had been persuaded to bring along from Texas. With astonishing speed Lyndon mastered the essentials of coping with the 500,000 constituents of his boss, the mysteries of congressional manipulation, and the complexities of the Federal bureaucracy. As his mentors he enlisted the whole Texas delegation, including “Tex” Garner and Sam Rayburn, made friends with them all and acquaintance with dozens of other congressmen. He was “entranced” by the Share Our Wealth program of Huey Long.

Advertisement

In the depression years of 1931–1935 there could hardly have been a better training for a politician and a more thorough education in the needs of a supporting constituency. Johnson was an enthusiastic Roosevelt New Dealer and supporter of the fifteen major laws of the Hundred Days that changed American life. No liberal ideologue, however, he could talk like a conservative with conservatives and was impressed with how little ideas figured in Texas campaigns. When the National Youth Administration came along, he seized the opportunity of becoming head of the Texas NYA and saw the job not only as a way of discharging his passion for helping the poor and jobless but as a means of establishing a local constituency and statewide contacts for future campaigns. Leaving Washington in 1935, he declared to a friend, “I’m coming back as a Congressman.” And so he did.

Johnson’s vigorous work for the NYA won praise from blacks and whites, and from the national administrator, who called it a “first-class job,” an outstanding “example to other states.” Lyndon also attracted a visit from Eleanor Roosevelt to find out why he was “doing such an effective job.” When the congressman from his district died in February 1937, Lyndon entered the race for the nomination against older and more experienced politicians. In time and energy spent campaigning and identifying his candidacy with the New Deal and FDR, he had no equal among his five opponents. He wound up in the hospital with the loss of his appendix and thirty pounds, but he won hands down over his closest opponent.

Visiting Texas the following month, FDR gave conspicuous attention to Congressman-elect Johnson, who “came on like a freight train,” according to the President. “I like this boy,” he told Harold Ickes. Lyndon returned to Washington in much the same “freight-train” manner. Ickes was soon calling him “the only real liberal in Congress” from Texas; Tommy (“The Cork”) Corcoran declared him “the best Congressman for a district there ever was,” and a lonely Sam Rayburn made the Johnsons “his surrogate family.” Roosevelt learned to lean on Lyndon, his “political magic,” and his Texas financial angels in congressional elections, and he gave the young man generous credit for saving the Democratic majority and gaining six seats in the 1940 election.

In return for his services the President threw his support behind Lyndon’s campaign to win a special election to fill the Senate seat left vacant early in 1941 by the death of the incumbent from Texas. For one thing, White House intervention stopped an FBI investigation of Johnson for violations of campaign laws in 1940. With three strong rivals in the race against him, however, and the polls showing little chance of his winning, Johnson came down with afflictions variously described as “throat infection,” “depression,” and “nervous exhaustion” that “made him irrational” and landed him in the hospital for nearly two weeks in the midst of a hot campaign. With more financial support from rich backers than any of his opponents, Johnson came back powerfully, wound up leading his closest opponent “Pappy” O’Daniel by 5,100 votes, with 96 percent of the vote counted, and claimed victory. But the reported margin of votes revealed just how many of the withheld returns his opponent had to “count” or “change” to reverse Johnson’s lead and win. “The fraudulent returns did the job,” concludes Dallek. Lyndon took his loss bitterly, but learned a lesson about winning elections in Texas.

Having wangled a naval commission as lieutenant commander, Johnson also managed to get orders in 1942 for a brief tour of duty in the Pacific and thereby earned a “war record.” He did take part (unnecessarily) in a dangerous bombing mission, came under fire that caused fatalities, and was awarded a Silver Star by General MacArthur. It proved a much displayed and politically useful medal. With a letter saying the President deemed his services “more urgently required” in Congress than in the navy, Johnson returned to the House.

One urgent requirement of Lyndon’s was to save the Brown brothers of Houston, the powerful building contractors who had been in trouble for under-the-table gifts to his campaign fund in 1941 (and now had large war contracts), from criminal charges by the IRS for tax evasions of more than a million dollars. Roosevelt proved extremely helpful in calling off the IRS charges against the Browns. It was in this period that the Johnsons bought the failing radio station KTBC in Austin in Lady Bird’s name. The granting of radio and TV licenses was a source of power and money for more than a few congressmen. Johnson used his political influence to gain favors that turned a failed station into a very profitable enterprise. While he probably regarded his profits from the station as a deserved reward for public services, his biographer holds that “Lyndon was walking a thin ethical line.”

In 1945 Johnson was still seen in Texas as an all-out New Dealer. After Roosevelt’s death he found much in common with Truman and continued his vigorous support for relief of the homeless, the jobless, the hungry; and on no issue was he more eloquent than on the need for Federal help for health care. He favored a cooperative approach to the USSR and denounced incipient McCarthyism. But Texans had grown richer and more conservative during the war, and in his race for reelection in 1946 they made him fear for his political life. He pulled back from Truman’s civil rights policy, voiced conventional southern views on race, and turned against unions and strikes. He won a decisive reelection victory, but began a three year period of uncertainty about his political direction.

Facing his second race for the Senate in 1948, Johnson continued his cautious shift to the right, keeping one foot in the other camp. This time, if defeated for the Senate, he would have to give up his seat in the House and face retirement. His poor prospects and his anxieties were intensified during the campaign by a severely painful kidney stone that once more put him in a hospital during a crisis. He fought his way back with a sensational blitz campaign by helicopter, “The Johnson City Whirlwind,” in which he visited 118 towns and cities in seventeen days. It was a very expensive campaign, financed by “a lot of money”—the total remains unknown—contributed by rich donors who had received lavish favors from Johnson that are spelled out in detail by Dallek.

Former Governor Coke Stevenson, his leading opponent in the Senate race, also received large contributions, mainly from major oil companies. As lieutenant governor, he had become governor in the election that had counted out Johnson in 1941 and elected Governor O’Daniel to the Senate. Romanticized by some as a strong, silent, cowboy type, a guardian of tradition and conservatism, Stevenson was a Dixiecrat who made much of opposing civil rights, keeping blacks in their place, and the big oil concerns happy. Starting off well in the lead, he ran a poor campaign, failed to win the first primary, and was forced into a run-off against Johnson.

The vote was so tight in the run-off that “no one could be sure who won,” and both sides plunged into the skulduggery of “correcting returns,” stuffing ballots, and buying up local bosses. Johnson was determined not to be counted out as he had been in 1941 and gave the necessary orders. So did Stevenson. For six days after the second primary the count seesawed between candidates as returns were competitively manipulated and the election was reduced to farce. Johnson was declared winner by an absurd 87 votes at the last minute. “No one will ever be able to answer with any certainty,” concludes Dallek, the question of who deserved the nomination. Johnson thwarted an attempt of Stevenson to get his name removed from the ballot by a friendly Federal judge on grounds that he won the primary by fraudulent votes. Johnson accomplished this by taking Abe Fortas’s advice to petition Justice Hugo Black; and he may also have had help from Harry Truman’s adviser Clark Clifford. He passed off the embarrassments of the election by jokingly calling himself “Landslide Johnson,” but he entered the Senate under a cloud, and he knew it. To reduce that election, however, to a conflict between right and wrong, innocence and guilt, would be an exercise in futility.

The new senator set out to recover his reputation and keep his nose clean for reelection in 1954. Avoiding anything Texas considered controversial, he took a turn to the right, joined in the sport of red baiting, and implicitly acknowledged the truth of the statement by his aide Harry MacPherson that the oil and gas industry was “a fact of life for any Texas Senator.” He avoided being labeled a southerner, while enjoying the advantages of being one by alliance with powerful southern leaders. He supported many Fair Deal reforms of Truman, but not his civil rights legislation—not “if I’m going to stay a senator.” Chaining himself and his driven staff to an eighteen-hour day, he quickly rose toward national leadership of his party. After two years he became at forty-three the youngest Senate Whip in party history, and after one more year Minority Leader, again the youngest ever.

Another stride to power came after he was returned to the Senate in 1954, an election in which Democrats gained control of Congress, and he became Majority Leader. Mustering all his talents for leadership, his command of Senate rules, the knowledge of his colleagues gained from a spy network he had built up over the years, and the almost physical coercion by what Doris Kearns calls “the treatment,” Johnson became, in Dallek’s opinion, “the most effective Majority Leader in Senate history.” With frenetic resort to night sessions, tricky quorum calls, horse-trading, cloakroom deals, and backroom agreements, he drove 1,300 bills through the Senate. His greatest legislative triumph was a public housing bill, and his major personal maneuver lay in organizing the bipartisan vote in the Senate that brought about the downfall of Senator McCarthy.

One price for all this was a coronary occlusion and a fifty-fifty chance for survival. Following that came a spell of depression that required medical attention and much patience on the part of Lady Bird. These afflictions discouraged talk of presidential aspirations in 1956, but after a couple of months’ rest at the ranch he appeared recovered. An offer then came from Joseph P. Kennedy of financial backing if Johnson would announce his intention to run for president and make Jack Kennedy his running mate. Lyndon sent word that he would not run against Eisenhower, and Kennedy became the running mate of Adlai Stevenson. This rejection by Johnson infuriated young Bobby Kennedy and began the feud that grew in intensity as the two men grew in prominence.

Steering a middle course between liberals and conservatives was one part of Lyndon’s strategy for getting the nomination in 1960, and refusing to admit his candidacy another. The civil rights issue could no longer be avoided. He had been one of three southern senators who refused to sign the Southern Manifesto signed by 101 southern congressmen against Brown v. Board of Education in 1956. If he could put a major civil rights bill through the Senate in 1957, the first in eighty-two years, it would, he no doubt calculated, lift him from the status of a regional to that of a national leader and greatly enhance his presidential prospects. But there is persuasive evidence of Johnson’s sincerity about racial equality—as much sincerity as a politician could then afford. Anyway, he threw an amount of energy into the effort that was described as “atomic.” When Eleanor Roosevelt visited his office he told her, “I’m here every night all night, day and night, but where are all the liberals?” The bill as amended and passed received mixed reactions from liberals. Mrs. Roosevelt called it “fakery” while Reinhold Niebuhr hailed it as “a great triumph of democratic justice.” Enraged southern politicians denounced it as Hitlerism, bayonet rule, and betrayal. A genuinely effective Johnson bill for civil rights had to wait until 1965.

Acknowledging that Lyndon had a powerful claim on his party for the 1960 nomination (“He’s earned it”), John Kennedy thought “it’s too close to Appomattox” for him to win, “So, therefore I feel free to run.” Adlai Stevenson felt the same about Johnson’s chances. Knowing and partly sharing this view, the Texan still could not bring himself to renounce and halt promotion of the nomination even while denying he wanted it. As for Kennedy’s rise, “It was the goddamndest thing,” he later said, and “his growing hold on the American people was simply a mystery to me.” He nevertheless aided the “whippersnapper” up to a point, while continuing an aggressive, if unconfessed, race himself. But as JFK put it, “Johnson had to prove that a Southerner could win in the North, just as I had to prove a Catholic could win in heavily Protestant states.”

As it turned out, of course, LBJ remained a “regional candidate” for the time being, while JFK became a “national candidate.” In the opinion of Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Johnson had good reason to want the second place on the ticket. He had exhausted the possibilities of majority leader and tired himself out in the process. Besides, he had a “deep sense of responsibility about the future of the South in the American political system,” and if a southerner were still denied a place on the ticket in 1960 the South would be driven back further into defense of the past “and into self-pity, bitterness, and futility.”2 What seemed to help the Kennedy-Johnson ticket most was the public (and widely televised) abuse Lyndon and Lady Bird received from right-wingers in Dallas four days before the election.

Robert Dallek takes his subject through the election of 1960 in Lone Star Rising, the first of two large volumes that promise to be by far the best and fairest biography we are likely to have for a long time. He does not neglect Johnson’s gross and unsavory aspects, but neither does he dismiss the potential for greatness. Without attempting to categorize him by region, class, generation, or party, Dallek leaves him sui generis.

Joseph A. Califano, Jr., has written an entirely different, though quite as interesting, kind of book. His Triumph & Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson is a memoir of the author’s three and a half years, beginning in July 1965, on the White House staff as assistant, “day and night…every waking minute of his presidency.” His day could begin at the side of the big four-poster containing the first lady as well as her mate, continue with the latter stripped bare through shave, shower, and on the john, then proceed all day into the night, sleep interrupted by phone at any hour. An insider’s view of the inside, the memoir spares no aspect of its complex subject: “Altruistic and petty, caring and crude, generous and petulant, bluntly honest and calculatingly devious.” Anecdotal, informal, and sometimes carelessly written (“the Achilles heel in the President’s jawboning program”), Califano’s book is always readable, forthcoming, and shrewd—although one must remember that Califano himself was deeply involved in many of the events he describes.

The new assistant came on just at the time that LBJ was making the critical decision to step up the war in Vietnam. That war and the War on Poverty are the antipodal themes of Califano’s book, thesis and antithesis with no synthesis in sight, back and forth from beginning to end. In his decision to pursue the Vietnam War Johnson is seen as doing what he thought John Kennedy would have done and what Kennedy’s top advisers were now pressing him to do. Califano soon realized his new boss was making another big decision at the same time: “Unlike Roosevelt and Truman, Johnson was not going to let his war destroy his progressive vision.” He would fight the War on Poverty simultaneously with the one in Vietnam.

From Johnson’s point of view the two decisions could not have come at a worse time, in the middle of what he described as “the most productive and the most historic legislative week in Washington during the century.” Here he was, having got through Congress many of the programs promised by the New Deal, the Fair Deal, and the New Frontier, and now on the eve of fulfilling his own dream of the Great Society—all threatened by events ten thousand miles away. Among his accomplishments threatened were the changed role of the Federal government in American life and a virtual social revolution that brought about Medicare and Medicaid, a real Civil Rights Act to replace the poor one, a Voting Rights Act, the Affirmative Action plan, an extensive housing bill, consumer protection laws, air, water, and noise pollution laws, funding for preschool, primary and secondary school, and higher education, National Endowments for the Humanities and the Arts, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the Freedom of Information Act, the Office of Equal Opportunity—these among many.

Vietnam was not the only threat. All along Johnson received much more abusive mail for his racial policies than for his Vietnam policies. “I think we delivered the South to the Republican party,” he remarked on his huge 1964 victory, after losing five southern states, four of which Democrats had not lost for eighty-four years. Nothing daunted, he went right ahead through the violence of 1965 in Selma and Birmingham to unveil his Voting Rights Bill in the famous “American Promise” message to Congress ending in the words, “And we shall overcome.” After a second of frozen silence one southern senator exclaimed, “Goddam!” and then almost all rose in a thunderous ovation. The following August the President signed the Voting Rights Act. “I would rarely see him happier,” says Califano.

Then five days after this monumental achievement, after suits were filed to void poll taxes and other voter limitations in southern states, at the very peak of Johnsonian euphoria, came the news of Watts. Four days of rioting, looting, and burning by thousands of blacks took more than twenty lives and injured some six hundred. Police Chief William Parker of Los Angeles blamed it on a president “telling people they are unfairly treated” and teaching them “disrespect for the law.” Watts marked the beginning of four “long hot summers” of racial riots, 150 major ones mainly in northern cities, that were to get much worse. Black nationalists preaching violence replaced leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr., and his doctrine of nonviolence.

Fully aware that time was running out, Johnson brushed aside all outcry against civil rights and blacks and raced ahead with his War on Poverty and Great Society program like a man pursued by a time bomb. On January 12, 1966, he startled a joint session of Congress with a new set of legislative proposals, demanding that “the representatives of the richest Nation on earth…bring the most urgent decencies to all of your fellow Americans.” In October he was able to celebrate the passing of a grand total of 181 out of the 200 measures he had proposed, most of them addressed to the health, housing, education, safety, employment, environment, and welfare of the poor. “There never has been an era in American history,” he boasted, “when so much has been done for so many in such a short time.” Explaining his method, LBJ told Califano, “You got to learn to mount this Congress like you mount a woman.”

After that it was downhill nearly all the way at a sickening pace. In the November 1966 elections the President’s party lost forty-seven seats in the House, three in the Senate, and eight statehouses. The President was suffering a loss of credibility, and Vietnam was the main cause. Part of the trouble was his unduly optimistic reports on the war’s progress and his way of becoming the most gullible victim of his own propaganda. Other causes of incredulity were his unrealistically low budgets and his insistence on guns and butter—the “butter” an enlarged agenda of Great Society reforms. “The President is simply not believed,” declared one of his staff in a closed session. The press were filled with leaks from current and former officials who said that his claims of progress in Vietnam were not credible.

Wave upon wave of protest broke over the White House—protests against the war, the draft, the bombing, the casualties. Universities supplied critical ideas, students most of the protesters, despite the favoritism they enjoyed in draft exemption. Draft-card burning became a popular ritual. Across the front lawn of the White House came chants of “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids have you killed today?” The slogan of young black mobs was “Burn, baby, burn!” as they set fire to their own neighborhoods in two dozen cities during the two years after Watts. When the 15,000 federal troops sent in by Johnson finally restored order in Detroit, forty-three people were dead, more than a thousand injured, and fourteen square miles had been gutted by fire.

Meanwhile the war worsened in Vietnam as casualties mounted, nearly a half million troops were committed, and none of the long-promised victories or peace negotiations materialized. Instead came the full-scale Tet assault of North Vietnam against South Vietnam’s cities in February 1968. Antiwar demonstrations and disruptions made it dangerous or impossible for the President to appear in public. Califano felt “a sense of siege in the White House” and in a memo to Johnson reported that the failing war abroad and burning cities at home made the public feel that our society was “coming apart at the seams.” Secretary McNamara, soon to resign, and other top advisers who once counseled Johnson to send more troops to Southeast Asia were now “beyond pessimism,” and in private “sounded a chorus of despair” and saw no way of winning the war. Through it all LBJ “could not hurl programs at Congress and the public fast enough”: health, housing, education, model cities, mass transit, child care, scenic rivers—on and on.

Events closed in. Congress balked at the domestic reforms, the public at the war, and Eugene McCarthy and Robert Kennedy entered the race for president in March 1968. At the point of exhaustion, Johnson made his surprise announcement: “I shall not seek—and will not accept….” Only then came the praise and applause long withheld by the press, return of support for his bills in Congress, and cheers instead of boos from crowds at Chicago next day, and then in New York. For a month or so he seemed something of a hero. His popularity soared.

But then began the awful succession of disasters that blighted his remaining months in office. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated, and flames flared over a hundred cities across the country, the worst over the capital. Johnson ordered in troops and marines to patrol the streets. Two months later Robert Kennedy fell before an assassin. Lyndon Johnson had watched bitterly as blacks and the poor had begun to adulate Kennedy. But in Kennedy’s death he saw an opportunity to press Congress for gun-control laws, as after King’s death he had pressed for fair housing. Both measures were defeated. Meanwhile, as his top officials resigned, he suspended the bombing in a futile attempt to bring peace in Vietnam before he left office. Through all this he never ceased frantic efforts to expand his vast program of social legislation and actually got Congress to enact much more of it in his final days, including laws against noise pollution by aircraft and laws to establish three new national parks and several new wilderness areas. His State of the Union address contained a proud summary of his achievements before an emotional Congress.

Califano emphasizes the pathos of Johnson’s years in the White House and the paradox of a president who had unprecedented success in passing social legislation and unprecedented failure in a misconceived military intervention abroad. What more can be said about his administration? Perhaps a good deal more, once serious efforts are made to understand the mysteries of political history since the time of LBJ. For example, the complete reversal of party fortunes and the succession of Republican triumphs, the Democrats’ losses among their traditional constituencies of working-class and middle-class voters, the conflict between minority rights and majority values, the popular association of social programs with waste and of wasteful, if victorious, little wars with “leadership.”

Accompanying these developments have been a growing indifference to corruption in the Federal executive department, presidential subversion of constitutional restraints, the growth of poverty, decline of real wages, and flagrant favors to the rich. Conspicuous also are an increasing tolerance of decline in health care, housing, and education to third world standards, chaos in the Federal budget and debt, and a display of cynicism in the White House that exceeds all previous records. Closer scrutiny of the LBJ years is a good way to begin the study of these mysteries.

This Issue

December 5, 1991