George Smiley, John le Carré’s melancholy spymaster, has the right take, I think, on the British taste for spying. It has much to do with class; specifically, with that great institution where class is instilled: the British public school, with its arcane rituals, its lifelong loyalties and resentments, and its cloistered cabals, where intrigues thrive.

Early on in le Carré’s latest book Smiley gives a speech to young secret service recruits (a speech, by the way, which recurs at the beginning of each chapter, sparking off another story, narrated by Ned, the world-weary, Anglo-Dutch intelligence agent on the verge of his retirement). In this speech Smiley wishes his audience to remember that “the privately educated Englishman—and Englishwoman, if you will allow me—is the greatest dissembler on earth…. Nobody will charm you so glibly, disguise his feelings from you better, cover his tracks more skilfully or find it harder to confess to you that he’s been a damned fool…. Which is why some of our best officers turn out to be our worst. And our worst, our best.”

I once met an Indian in Delhi, a distant relative of one of the grander Rajput maharajas, who explained to me what he had learnt at Mayo College, the Indian equivalent of Eton. “Dear boy,” he said with a most charming smile, “I learnt how to eat with knife and fork—a most bourgeois accomplishment, don’t you think?” And what else did he learn? “Ah,” he said, smiling to himself this time, “I learnt how to be cunning.”

The art of survival through charm and if necessary deceit is an accomplishment eminently suited to diplomacy and spying. But there is, as always, a price to pay, a price which is at the core of Smiley’s character and le Carré’s art. It is a vague sense of inner emptiness, of having dissembled for so long that only the mask remains. The Secret Pilgrim is about the spiritual longing of men who have mislaid their passions, lost their moral anchors. The cold war, despite all its moral ambiguities, provided some kind of anchor, but even that’s no longer there, now that the cold war is apparently over.

The alleged lack of passion among bourgeois Englishmen is another thing that helps in the spying trade: one can resist temptations and the mind is unbound by serious commitments to anything much, least of all to an idea. Spies an be tripped up easily by their passions (they often are). Cynicism offers more protection. You might argue that the notorious Cambridge spies were both consummate professionals and committed ideologues, and that their very seriousness was one reason for turning against a country (and a class) that was so unserious, but one wonders how committed even they were to their political ideals.

There is an interesting line in An Englishman Abroad, the superb television film about Guy Burgess, written by Alan Bennett and directed by John Schlesinger. When Burgess (Alan Bates) meets the actress Coral Browne in Moscow, she asks him why he did it, spy, that is. It was about ideas, he says, and that is something the English would never understand. Maybe it was about ideas, but everything known about Burgess pointed to a rather frivolous man. He was by all accounts clever, charming, cunning, and snobbish, indeed the perfect public schoolboy. But as is so often the case with charming English gentlemen, one has the impression of a man whose cleverness expressed itself in juggling with ideas, as though they were part of a music hall turn.

Le Carré’s spies are not frivolous, but they are men whose lifelong immersion in deceit and moral ambiguity has damaged their humanity. Here is Ned, the narrator of The Secret Pilgrim: “And when I looked at myself in the mirror of the undertaker’s rosetinted lavatory after my night’s vigil, I was horrified by what I saw. It was the face of a spy branded by his own deception.” Sherlock Holmes at least had his violin and his opium dreams to ease his cut-glass mind and restore his humanity. Smiley’s people have nothing of the sort. They are in a permanent spiritual Greeneland, on a hopeless quest for absolution.

This isn’t only true of the British public schoolboys. Their East bloc counterparts share the same predicament. Take Colonel Jerzy, Polish spy chief, torturer, double agent. He decides to betray his side and hand over information to the British. Why? ” ‘No danger is no life,’ he said, tossing three more rolls of film on the counterpane. ‘No danger is dead.’ ” This really is the heart of Greeneland. One day Ned turns on the television news. It is a meeting of Solidarity, with the cardinal giving his blessings. And there is Colonel Jerzy, in the background at first, but then kneeling at the cardinal’s feet, his eyes closed, apparently in pain: “But what is he repenting? His brutality? His loyalty to a vanished cause? Or his betrayal of it? Or is squeezing the eyes shut merely the instinctive response of a torturer receiving the forgiveness of a victim?”

Advertisement

Much is made in interviews with le Carré and reviews of his last two books of the supposed end of the cold war. Can he still go on writing his spy novels? Must he look for another enemy, another subject? In fact, I think too much is made of this. The cold war was never more than a frame for his stories anyway. His real subject is rather like Graham Greene’s: man’s, especially Englishman’s, struggle with his soul. But, if not the cold war, le Carré does need some kind of model for his stories. Like Raymond Chandler, he is at his best when he expands the limits of his chosen genre. But without the genre he is at sea. In his latest book, the frame is barely there; instead we have a series of episodes, knitted together by Smiley’s speech. It is little more than a loose bit of string to tie up various good ideas for stories that never made it into his other books.

Some of the stories are not even very good. The weakest chapter is set in Thailand and Cambodia. Perhaps it is based on a real story, but to me the idea of a European traveling through Pol Pot’s Kampuchea in search of his Eurasian daughter, finding her, being arrested by the Khmer Rouge, being released, and finding his daughter back in a camp in Thailand is utterly fantastic. In real life the Eurasian daughter would have had virtually no chance of survival, let alone her white, imperialist father.

The point of the story is that the white man, called Hansen, an Anglo-Dutchman like Ned, has, unlike Ned, found a real passion, a reason to live. His passion is for his daughter, who ends up working as a lowly prostitute in a Thai brothel, where Hansen grovels around at her feet. Everything, from the lush descriptions of the Cambodian jungle to the romantic rantings of Hansen about the spirit of Asia, comes off like a bad imitation of Conrad. And Hansen, alas, is no Kurtz.

After this Asian excursion, it is a relief when Ned’s memory abruptly turns again to the soggier but surer ground of England. Le Carré’s description of the office politics inside the Circus is, as always, beautifully contrived, cold war or no cold war. Of course office politics are just as lethal in other countries, but perhaps because of the class war, and the veneer of good manners, the British can give it a particularly nasty twist. Le Carré’s Circus bears an uncanny resemblance to a wholly different British-dominated organization for which I once worked abroad. There, too, the ranks were sharply divided between what a colleague used to call “the officers and the NCOs,” meaning, in our case, university-educated journalists and editors manning the copy desk.

The copy editors regarded themselves as “pros” and the writers as “wankers.” The journalist officers, on the other hand, saw the NCOs as useful drudges at best, to be humored once in a while with a beer at the club and to be patronized the rest of the time. On the surface everyone was perfectly polite, but as an American old hand warned me when I started my job, “Boy, when those Brits start shooting, you’d better keep your head down.” Real shootouts were actually rare, but the sniping, the subtle social slights, the wounding little flicks at the other’s self-esteem, the winks and nudges of class solidarity, these went on without pause.

This is the world that produced the likes of Peter Wright, the author of Spycatcher, whose obsessions with upper-class moles and traitors were fueled by deep resentments.1 Wright was a typical NCO, a technical man, a drudge. In 1945 George Orwell described this “new kind of man,” produced by the demands of modern industry: “People like radio engineers and industrial chemists, whose education has not been of a kind to give them any reverence for the past, and who tend to live in blocks of flats or housing estates where the old social pattern has broken down.”2 The point is of course that the new kind of a man was distinctly not a gentleman.

Le Carré describes such men well. His Peter Wright, so to speak, is called Monty. Like Wright, Monty is a technical man, a bugging expert, a dirty-tricks operator. Once in a while, in the course of his duties, Monty has access to the grander tables above his normal station. Le Carré puts him firmly in his place: “Monty, a white napkin at his throat, is seated between the sedate Misses Quayle and wiping the last of his cannelloni from his plate with a piece of bread while he regales them with accounts of his daughter’s latest accomplishments at her riding school.” The napkin, the bad table manners, the vulgar pride in the daughter and her riding school, all underline le Carré’s distaste.

Advertisement

Naturally, the Montys of this world are perfectly well aware of this, and their loathing of the officer class is as deep as their longing to acquire its trappings (riding schools, and the like) for themselves. Le Carré’s own perch in the class hierarchy is easy to identify with some precision. He is what Orwell described as “lower upper class,” which is where Orwell placed himself, too. It is the class of professionals, whose sons are sent to decent public schools. When they go to Eton, like Orwell, it is usually on a scholarship, or, like le Carré, as a teacher. Their attitude to the upper class can be complicated, in some cases a mixture of fawning snobbery (Evelyn Waugh, Cyril Connolly) and the wish to kick it in the shins (the Cambridge spies). Their attitude to the NCOs, especially newly rich NCOs, is almost invariably one of disdain.

The Cambridge spies were all snobs and all had an axe to grind with the upper-class “establishment.” This axe could be the result of an unorthodox sex life, or anything that set them slightly apart from their fellows and might have met with disapproval. The cases of Burgess and Blunt are well known. Kim Philby, the scion of colonial administrators, was impeccably lower upper class, but his mother had Indian blood, which in itself might not have constituted an axe, but surely added an extra layer to Philby’s complex character. Some of le Carré’s heroes, Ned for example, also have foreign mothers. Ned, as well as his illfated friend Ben, whose mother was German, “were both, perhaps by way of compensation, determinedly of the English extrovert classes—athletic, hedonistic, public-school, male, born to administer if not to rule.”

And Ned, in the manner of his station, despises Monty, but has little time for the ruling class either. He hates their supercilious manners and their effortless air of superiority. About two foreign-office types, both “members of the English governing classes”: “Everybody was smiling at me. They would have smiled whatever I had said. They were that sort of crowd.” Or this: “The second Foreign Office man was round and shiny with a chain across his waistcoat. I had a childish urge to pull it and see if he squealed.”

This is all mildly amusing. Less funny, but just as much part of the lower-upper mentality, is the crude anti-Americanism that pops up in le Carré’s work. Americans, one senses, are not only blamed for having usurped British power, but they have the same boorish manners and lack of “reverence for the past” as the British lower middles. And why, oh why, does every American walk-on character have to be called Milt or Sol? In his easy liberal way, le Carré deplores that old class enemy, “Western materialism.” He hates Mrs. Thatcher, at whom he has a rather stale swipe, and what she did to Britain. The main gripe against Mrs. Thatcher’s Britain and the USA is that the wrong people got rich.

This is a conventional attitude among liberal British novelists, which shouldn’t matter much. The best writers can have appalling opinions, as long as their art doesn’t suffer. With le Carré, whose opinions are not appalling, just predictable, the art, which in his case must be plausible, does sometimes suffer. This shows especially in his last chapter, where a villain appears who is more odious than any other, far worse even than the Polish torturer. Sir Anthony Bradshaw, the filthy-rich arms dealer, is a caricature of the wicked Thatcherite parvenu. He is rich, loud, boorish, racist, greedy, selfish, and probably, though le Carré doesn’t say so, ties up little girls as a hobby. He was a school bully, of course. He speaks in “sawing nasal tones.” His walk has “menace in it, and impatience, and a leisured arrogance.” Worst of all, he talks about “niggers.”

Here, then, is a man who combines the vulgarity of the lower middles, the Montys, and the arrogance of the ruling toffs. He is not an interesting character, because unlike Smiley’s communist counterparts, he is made of cardboard. Where is le Carré’s famous moral ambivalence now? Ned visits Bradshaw at his enormous mansion in the beautiful heart of southern England—“The centre section was William and Mary. The wings looked later, but not much.” Ned sees him at his desk. “His gold cufflinks were as big as old pennies. Then at last he laid the pen down and, with a wounded—even accusatory—air, he raised his head, first to discover me, then to measure me by standards I had yet to ascertain.” Ned feels disgusted and humiliated, as he did when those insufferable foreign-office types kept on smiling, whatever Ned said. But at least they were bona fide members of the governing classes. Whereas Sir Anthony Bradshaw, well….

“Did you get a lordship of the manor when you bought this house?” I asked, thinking a little small talk might give me time to collect myself.

“Suppose I did?” Bradshaw retorted, and I realised he did not wish to be reminded that he had bought his house rather than inherited it.

The caricature is too broad, the irony too heavy. Just as the Yanks inherited the mantle of British supremacy, the wrong kind of people have moved into the stately homes of England. Ned wonders whether the cold war was worth winning, for this. He remembers Smiley’s aphorism about the right people losing the cold war and the wrong people winning it. It is once again a predictable, lower-upper liberal sentiment, which almost makes one forget that while the cold war lasted, it wasn’t the Montys who betrayed George Smiley’s England; it was the Blunts, Burgesses, and Philbys, jolly good chaps to the man.

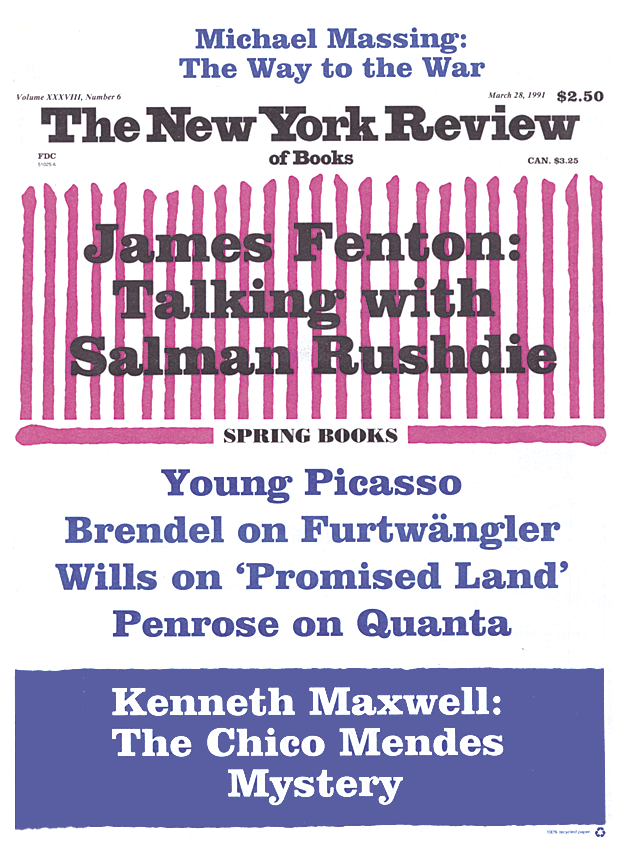

This Issue

March 28, 1991