In 1931, J. C. Squire edited a volume of essays by various hands called If; or, History Rewritten, which he described as “a number of speculations by curious minds as to the differences that would have been made had ‘events taken another turn.’ “1 The authors included Philip Guedalla, who considered what might have happened “if the Moors in Spain had won” and wrote a history of the independent state of Granada from 1491 to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919; G. K. Chesterton, who sought to make clear the favorable consequences in the long run, for the British Isles and for Europe, of a marriage between Don John of Austria and Mary Queen of Scots; and Hendrik Willem Van Loon, who discussed the complicated politics of the Atlantic seaboard after the Dutch had decided to remain in New Amsterdam.

In one of the liveliest essays in the book, Winston Churchill addressed himself to the historical repercussions of a Confederate victory at Gettysburg2 and described with gusto how this led, by way of a series of complicated and improbable events, to the foundation of a Union of the English Speaking Peoples that was strong enough to prevent the outbreak of war in 1914 and to lay the foundation of a united Europe, the inauguration of which was presumably to be celebrated in 1932, under the patronage of Emperor William II of Germany, whose forty-four-year reign had been a model of peace and social progress.

For the historian, this kind of conjectural history is an amusing challenge to the imagination, a game that can be played for any period, from ancient times until the recent past, in which his success will be measured by the plausibility of his invention. It is different with the writer of fiction. If the story he has to tell is to gain anything from being set in an invented past, that past will have to be recent enough to be within the memory of his readers, and his invention will have to bear some correspondence to what their own hopes and fears were at the time. A story that took place in a Rome that had lost the Punic wars, rather than won them, would gain nothing from the imagined context, which would merely confuse most readers. But a story placed in a Nazi Germany that has won the Second World War is bound to gain from its setting, since most people over the age of fifty in Europe and the West (and, thanks to television, the movies, and the verbal testimony of elders, many younger persons as well) know that such a victory was a real possibility and can recall their own feelings as they contemplated it.

1.

Like Len Deighton and Philip K. Dick before him, Robert Harris has profited from the great and continuing interest in Adolf Hitler in writing a thriller set in an age dominated by a National Socialist movement that has triumphed in the Second World War. The time is April 1964, almost twenty years since the end of that conflict. The German Empire now stretches from Luxembourg and Alsace and Lorraine to the Caucasus and the Urals. Czechoslovakia, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia have vanished from the map; the east is divided into four great Reichskommissariate, Ostland, Ukraine, Caucasus, and Muscovy; Cracow, Warsaw, Riga, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Tiflis are now imperial cities; and the Crimea, renamed Gotenland, has become the Riviera of the Reich, the greatest holiday resort in the world. The countries of Western and Northern Europe, including the British Isles, have been organized into a European trading bloc, in which

German was the official second language in all schools. People drove German cars, listened to German radios, watched German televisions, worked in German-owned factories, moaned about the behavior of German tourists in German-dominated holiday resorts, while German teams won every international sporting competition except cricket, which only the English played.

Except in the case of Switzerland, which alone remained unconquered during the war, all European governments are satellite bodies, entirely subservient to German policy. In England, Edward VIII and Queen Wallis are on the throne, Churchill and the royal family having fled to Canada, and there is a finishing school for higher SS officers at Oxford.

Having accomplished his early dreams of making a new order for Europe, Hitler has also carried out the grandiose plans for the reconstruction of Berlin that he elaborated with his architect, Albert Speer, during the war years. The old capital is now dominated by an Avenue of Victory three miles long, lined by gigantic new ministries designed by Speer. At its midpoint there is an Arch of Triumph made from the Führer’s own plans and so large that forty-nine Arc de Triomphes could be fitted into it. Even more stupendous is the Great Hall of the People, standing at the apex of the avenue, the largest building in the world, with a dome that projects a kilometer into the sky, so that its top is often hidden in the clouds. Used only on the most solemn occasions, it is capable of accommodating 180,000 people and, when it does so, it creates its own weather, for their collective exhalations form clouds that condense and turn into a light rain. In keeping with Hitler’s fascination with sheer size, visitors are always informed that the Dome of Saint Peter’s in Rome would fit into it sixteen times.

Advertisement

It cannot be said that all is well in the Greater Reich in 1964. The war that supposedly ended in 1946 has been replaced by a cold war, and, beyond the Urals, Russian forces, supplied by the United States, carry out depredations along the frontiers. The plan, originally drawn up by Himmler, to have 20 million German settlers in the east by 1960 and 90 million by the end of the century has misfired badly, for the settlers keep trying to come back to their original homes. The disorder caused by this has been accompanied by so great a degree of terrorism on the part of the subject peoples that the police in the capital are on a perpetual terrorist alert.

More ominous is the alienation of the younger generation, which, particularly in the universities, carries on a resistance against the establishment that takes the form of adulation of non-Nazi art forms (the music of the Beatles, for example), antiwar demonstrations, and the revival of the White Rose Society, which had been suppressed in 1942 after the execution of its leaders Hans and Sophie Scholl and their teacher Professor Kurt Huber. Concern over these matters is offset to some extent by the excitement and renewed patriotic feeling caused by the pending celebration of the Führer’s seventy-fifth birthday and by the exhilarating news that the president of the United States, Joseph P. Kennedy, who is running for reelection in November, will fly to Berlin in the fall to talk with Hitler and lay the basis for a détente agreement between the two powers.

It is against this background that Harris sets his story. On a rainy April night the body of an elderly man in swimming trunks is dragged from the waters of the Havel Lake, near the well-to-do suburb of Schwanenwerder on the western outskirts of the city. Harris’s hero, Xavier March, a homicide investigator for the Criminal Police, falls heir to the case by a kind of accident. It is not his turn on the roster, but he takes it in order to do a favor for a colleague. A former U-Boat commander and decorated war hero, March is a lonely man, divorced, estranged from his ten-year-old son and considered by his superiors to be asocial, “one step down from traitor in the Party’s lexicon of crime,” a noncontributor to Winter Relief and other Party charities, a nonjoiner of National Socialist organizations, a man too good at his job to be dismissed but too independent ever to be promoted.

In his preliminary investigation, March learns that the drowned man was an Alte Kämpfer, who had joined the Nazi Party in 1922 and had been arrested along with Hitler after the Munich Putsch of the following year. He later worked with Hans Frank, Hitler’s own lawyer, and in 1939 became state secretary in the General Government of Poland and was given the honorary rank of SS Brigadeführer.

Shortly after he makes these discoveries, March is informed by the Gestapo that it is taking the case out of his hands. A stubborn man, with more than his share of curiosity (he has always wanted to find out what became of the former tenants of his apartment, whose name was Weiss, and who were, he has been told, Jews), March disobeys this order and embarks on a course of action that threatens the fate of the pending German-American negotiations and perhaps the future of the Great German Reich itself. For at the end of his trail lies the key to the Nazi regime’s best-kept secret, what happened to the Jews after they were transported to the East; and, by persistence and luck, and the cost of his own life, March discovers official documents that answer this question irrefutably and manages to have them communicated to the American press.

This is not an unfamiliar kind of story, and it would probably be doomed to imminent oblivion were it not for the skill with which Harris has constructed the imaginary world in which it takes place. In The Mikado, Pooh-Bah talks of the importance of “corroborative detail [in giving] artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative.”3 With respect to verisimilitude, this novel leaves little to be desired. Mr. Harris has done his research well. He is familiar with the real Berlin and its climate and its moods; he knows the Berlin that Hitler, with his maniacal fondness for gigantism, was intent on creating; and he has studied the history and organization of the Nazi Party and the nature of its bureaucratic practices. On the basis of this knowledge, he has created an entirely credible picture of a cruel and corrupt system that is systematically bent upon concealing the darkest pages of its past and ruthless in destroying anyone who threatens to expose them.

Advertisement

At only one point is Harris’s reconstruction less than plausible, and that is in his sketchy description of how Hitler managed to win the Second World War. We are told that victory was the result of the Führer’s brilliant strategy in 1943 in the space between Moscow and the Caucasus, which led to a Soviet surrender, followed in 1944 by a U-Boat campaign that forced the British to capitulate and the explosion of a V-3 rocket over New York in 1946, which persuaded the Americans that Germany had gained nuclear parity with them and that a cessation of direct hostilities was advisable. But informed military opinion inclines today to the view that, after Hitler failed to take Moscow in 1941 and diverted most of his forces to secondary targets, he had lost the eastern war irretrievably,4 from which it would follow that Harris’s scenario for the defeat of the West wouldn’t work either. It might have been more logical had he had Hitler win his war in 1941.

2.

Harris says little about resistance to the Nazi state, except in his references to terrorism and student activities and his intimation that these may become more dangerous if détente fails or a major crisis develops. But the atmosphere of the system he has created reminds us how difficult resistance is in a mass society with a ruthless government, and this recalls the history and failure of the German resistance to Hitler in the 1930s and 1940s.

In April 1988, the Goethe House of New York sponsored a symposium on “The German Resistance Movement, 1933–1945.” This meeting, whose proceedings are published in Contending with Hitler, began with three general papers by Willy Brandt, Theodore Ellen-off, and Fritz Stern, and went on to discuss, among other topics, the socio-historical typology of the opposition to Hitler, the working-class resistance, the role of women and the Jews, the conservative opposition, the Kreisau Circle, the group led by Helmuth James von Moltke, who worked tirelessly to bring churchmen, laity, working-class leaders, and soldiers together in secret conferences for the purpose of planning a post-Hitler Germany,5 and the political legacy of the resistance.

In the course of their deliberations, the contributors came to agree with Willy Brandt’s expressed reservation about using the term “resistance movement.” The former Socialist chancellor said:

When I was a young man, we referred to ourselves as the opposition. Of course, we knew about the diversity of those opposing the Nazis, and we were aware of their inadequacy. Much of the persecution that took place was not provoked by active opposition; it was based solely on the different nature of some, and the sheer madness for extermination of others. And there was very little resistance deserving of the name that was not soon discovered, with the means available to the totalitarian regime at the time, or even destroyed before it ever got started.

The symposium members were also troubled, as the printed volume of their contributions shows, by the inflation of the word “resistance” to cover a wide range of different attitudes and activities. What exactly was “resistance deserving of the name”? Some of them tried to clarify the question by semantic refinement, distinguishing between nonconformity (listening to the BBC, refusing to hang out flags, detaching oneself from party activities, as Mr. Harris’s stubborn hero does, for example), selective opposition (on such issues as euthanasia and the attempt of the so-called “German Church” to subvert Church doctrine by diminishing the importance of Jesus Christ), and unconditional resistance to Hitler and all his works (Widerstand). The German historian Detlev Peukert sought greater precision by writing:

We can characterize the range of dissident behavior by using two parameters: the degree to which the behavior was public, ranging from “purely private” gestures to highly visible acts; and the degree of intentional challenge posed to the regime, ranging from merely isolated instances of grumbling to the intention to undermine the regime as such. Within this framework we can distinguish among types of conflict on a rising scale of complexity and risk, beginning with occasional, private nonconformism, proceeding to wider acts of refusal, and then to outright protest, in which some intentional effect on public opinion is involved. A form of behavior, finally, may be counted as resistance only if it was intended to make a public impact and to pose a basic challenge to the regime.

The result of this approach, Mr. Peukert concluded, was that

…we discover an astonishing variety of types of “nonconformist behavior” in Germany between 1933 and 1945 but little full-scale “resistance.”

Useful as this may be for the sake of categorization, it throws little light upon the high degree of ambiguity that characterized even those groups most clearly intent on putting an end to the Hitler regime or upon the motives of individuals who, without consulting anyone or seeking anyone’s help, sought to do what they could to defeat Nazism and its designs by themselves. With respect to the latter point, as the distinguished Smith College historian Klemens von Klemperer points out in his contribution to Contending with Hitler, we have a very imperfect idea of what led Georg Elser, a humble Swabian carpenter with no friends, to try to kill Hitler with a bomb in a Munich beer hall in November 1939, or what persuaded Franz Jägerstätter, a peasant from Upper Austria, to choose death rather than service in Hitler’s armed forces, or what induced the businessman Eduard Schulte to carry abroad information about the Final Solution and Germany’s military plans.

Such men fit awkwardly into Peukert’s schema. They were Einzelkämpfer, solitary witnesses, and Klemperer argues that, in the last analysis, almost all real resisters were solitary witnesses, since they were forced at the outset to resolve often anguished conflicts between their decision to help remove the Nazi regime, by force if necessary, and their patriotic or religious convictions, and also to face up to the knowledge of what dreadful consequences their chosen course might entail for themselves and their families. Even entering into a resistance group, therefore, “entails taking an existential step, and it is primarily the individual’s.”

And yet many who took that step were prey to deep ambiguities in their attitude to the foe they fought, and David Clay Large, in the introduction to his interesting and provocative collection, points out that this was particularly true of the clerical and conservative opposition, whose members “tended to share some of the principles, prejudices, and aspirations of the regime they (very belatedly) came to reject.” In particular, “the Christian conservative resisters’ tardy and inadequate response to the persecution of the Jews was the greatest moral failure of the German opposition….The ugly fact is that the Jews were a minorité fatale not just for the Nazis but for the majority of the gentile anti-Nazis.”

Victoria Barnett’s excellent book on the attitudes of the German Protestant churches toward the Nazi regime is replete with examples of this kind of ambiguity. There can be little doubt that most German pastors found much to admire in Nazi doctrines in the first years of the regime and began to suffer doubts relatively late. The Confessing Church, the most forthright in its opposition to National Socialism’s attempt to claim the entire person, had declared at Barmen in 1934 that Christ and the knowledge of him gained through the Bible was the only authority of the Church and the only source of revelation, and that the Church would not alter this witness to suit the goals of any political party. Yet the pink membership cards of the Church stated that “such a confession includes the obligation for loyalty and devotion to Volk and Fatherland.” Particularly after the beginning of the war, it became difficult to draw a line between fighting for the Fatherland and serving the ends of Adolf Hitler, not least of all for the 1,500 Confessing pastors who were soldiers.

When the deportation of the Jews began, the Confessing Christian Franz Kaufmann asked, “Should we go on as if nothing happened?” A great number of Evangelical and Confessing Church leaders not only answered in the affirmative but refused to regard this as in any way a capitulation to Adolf Hitler. Barnett writes:

On the contrary, many church leaders believed that the determination of the church to continue as a Christian church within a totalitarian system hellbent on destroying Christian values constituted a form of resistance. These church leaders simply believed that their task under Nazism was to preserve and protect the church.

When other pastors refused to agree—like Martin Niemöller, who paid for his open defiance of party decrees and behavior by years of internment in a concentration camp, and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who suffered death for his resistance activities—they were criticized by many in the Church. Shortly after the war, Bishop Meiser of the Lutheran Church of Bavaria declined an invitation to a memorial service for Bonhoeffer on the grounds that he was not a Christian martyr but a political one.

This sort of behavior should not be allowed to obscure the fact that many Protestant churchmen were brave and selfless Widerstandskämpfer and that others became bitter critics of their own previous conduct. At the height of the Allied bombing, Bishop Wurm of Württemberg, an early critic of the radical wing of the Confessing Church, reminded his congregation from the pulpit of the Church’s silence at the time of Reichskrystallnacht in November 1938 and said that the bombing was “God’s revenge for what was done to the Jews.” Similarly, Martin Niemöller, after the war, blamed the disaster that had befallen Germany less upon Hitler or the German people than upon the Church itself, which knew that Hitler’s course would lead to ruin and didn’t do enough to prevent it. But how far should the churches have gone? Until the very end of the regime, this proved a difficult question for most churchmen, and Barnett quotes Hebe Kohlbrugge, who was active in the Confessing Church before joining the Dutch resistance, as believing that such action was a question of individual conscience.

I quite agree with Bonhoeffer and von Trott who did it from their viewpoints as Christians….But I don’t think that the Council of Brethren should have been sitting around, saying, who can put the bomb under Hitler?

3.

The books by Klemens von Klemperer and Giles MacDonogh deal with what can be called the foreign policy of the German resistance, the attempts made to establish and develop contacts abroad with an eye to persuading other governments, particularly the British and American, to assist the Widerstand’s efforts to prevent the outbreak of war and, after 1939, its determination to terminate the conflict and to remove Hitler from power. The first is a meticulously researched and marvelously detailed account of the various groups that took part in this effort. It contains much new information, not least of all on a part of resistance history that has been neglected: the contacts of resisters after 1943 with the World Council of Churches in Geneva and the Nordic Ecumenical Institute in Sweden.

Giles MacDonogh’s biography of Adam von Trott was conceived as an attempt to produce a “clear and unequivocal book” about the life of the most determined and energetic of the resistance diplomats, whose motives and actions were so often misconstrued by his Western contacts and, later, his British biographers.

This was understandable. Trott was descended on his father’s side from an old and distinguished Hessian family; his mother came from the Prussian Junker family Schweinitz, and was also a direct descendant of the American Chief Justice John Jay, and she had close ties with the ecumenical movement, which influenced her son.

As a young man, Trott was a Socialist with cosmopolitan tendencies, strengthened by his years as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford. He hated and opposed Adolf Hitler from the moment of Hitler’s accession to power, but combined this feeling, in a way that confused his English friends, with a deep German patriotism, a belief in Deutschtum’s potential contribution to the birth of a new European society, and—as a Hegelian—a distrust in linear progression in history and a belief that the good emerged from the resolution of contradictions. He therefore decided to work against Hitler from within the system and became an official in the Foreign Office and, to facilitate that, a member of the Nazi Party. Altogether a complicated person, whose services to the resistance and the price he paid for them Mac-Donogh describes with sympathy and in rich detail.

Not surprisingly, the groups that were most active in resistance foreign policy were those whose members could find a legitimate reason for visiting foreign countries at a time when the privilege was denied to most citizens. There were four principal groups of this kind. The first—sometimes referred to in resistance circles as Die alten Herren—was led by General Ludwig Beck, chief of the army general staff from 1935 to 1938, Carl Goerdeler, former Oberbürgermeister of Leipzig from 1930 to 1937, when he resigned because of anti-Semitic and anti-Christian policies of the Nazi Party, and Ulrich von Hassel, ambassador to Rome from 1932 to 1938, when he was removed by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop because he opposed the admission of Italy to the German-Japanese Anti-Comintern Pact, on the grounds that it would increase the chances of war.

Beck, who believed that precisely because the German people had always had a pietas for their army it was the army’s duty to protect them against the consequences of Hitler’s megalomaniac ambitions, was, until the failure of the bomb plot in July 1944, the spiritual leader of the military resistance, and it was with his strong support that many of his junior colleagues went abroad in the years 1938–1939 to warn the West of Hitler’s war preparations. Goerdeler, masquerading as a representative of the Robert Bosch firm in Stuttgart, and Hassell, as a member of the board of the Central European Economic Conference, were able to travel frequently, and Goerdeler in particular went to the United States and repeatedly to Great Britain to urge that Hitler could be stopped only if the Western governments made it clear to him that they would resist further aggression with force.

These efforts were supported by those of a second group within the Wehrmacht’s military intelligence service, the Abwehr, where the enigmatic Admiral Canaris, while never neglecting his assigned duties (in 1942–1943 he penetrated British intelligence operations in Holland in an operation called “The English Game” which resulted in numerous deaths and arrests on the Allied side). nevertheless shielded the resistance activities of Colonel Hans Oster and others on his staff. It was Oster who in the fall of 1939 conceived one of the most ambitious of the resistance’s wartime operations. Determined to prevent the offensive in the West by a military coup, he sought, with the collaboration of his friend Hans von Dohnanyi and the Munich lawyer Josef Müller, to prevail upon Pope Pius XII to act as an intermediary with the British government to obtain assurances that the Allies would not take military advantage of the resultant turmoil in Germany.

A third center of resistance activities was the Foreign Office, where in 1938 and 1939 State Secretary Ernst von Weizsäcker worked through his diplomats in London and Berne to combat the aggressive policy of his Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and urged action by the British and French to forestall the conclusion of a pact between Germany and the Soviet Union, which, in his view, would make war inevitable. Here too, after hostilities had begun, Adam von Trott zu Solz, from his office in the information section and in frequent trips abroad, sought to inform foreign governments of the existence and the plans of the German resistance and to persuade them that some evident sign of interest on their part would increase the chances for army and popular support for a Putsch. Trott was also active in spreading abroad a knowledge of the activities of the fourth significant resistance group, the Kreisau Circle, led by Helmuth James Graf von Moltke, and in arguing persuasively that in their plans for a postwar settlement Western governments would be mistaken if they did not take into account the ideas that Moltke and his colleagues had developed for the future governance of Germany and the postwar organization of Europe.

The foreign policy of the resistance was, of course, a failure, and only a miracle could have prevented it from becoming so. Goerdeler’s warnings to the British government before the war were little heeded, and the elaborate Vatican exchanges planned by Oster in 1939 never got beyond the talking stage. (Indeed, the only positive result of those exchanges was a tragic one. On the basis of information supplied by Müller, Hans von Dohnanyi made an elaborate summary report on the discussions in Rome which he dictated to his wife and, disregarding warnings to destroy it after it had been read by his superiors, deposited in army headquarters in Zossen. Here it was discovered by the Gestapo in September 1944 and subsequently led to Müller’s imprisonment and the accumulation of new evidence against Dohnyani, who had been arrested for treasonable activities a year earlier.

The basic reason for the failure of these diplomatic efforts, which was never fully appreciated by the German opposition leaders who went abroad seeking understanding and support, was the extent of the hatred of Hitler and the distrust of German promises that had been engendered during the appeasement years. Adam von Trott, because of his student years at Oxford, had many friends in England and some useful connections in government circles; when he came to England on a mission in June 1939, he was distressed to find that his motives were distrusted even by his most intimate acquaintances.6 He failed to appreciate the fact that his hosts were bound to wonder why it was that he, an official of the German Foreign Ministry, was able to travel abroad unless he was serving some secret design of Hitler’s.

Trott’s purpose in coming to England in 1939, shortly after the German seizure of what remained of Czechoslovakia, was to persuade the British government to keep the door open for negotiations with Hitler and to take no action that would give him an excuse for war. Trott believed that if Hitler nevertheless resorted to hostilities he would do so without the support of the army and the German people, and therefore might be overthrown. His English friends found this argument unpersuasive and accused Trott of advocating appeasement. Richard Cross-man exploded:

You come along with all this damned peace of yours, but you don’t realize we don’t want peace with the Nazis. We’ve tried it and it doesn’t do…. We are hostile to the Nazis. We think they’re a lot of bastards. We want to defeat them, push them down, smash them.

Maurice Bowra of All Souls, whom Trott considered a friend, showed him the door, and, knowing that Trott was going to America, wrote Felix Frankfurter to warn him against Trott, a warning that Frankfurter passed on to the President, fatally offsetting the former Chancellor Heinrich Brüning’s recommendation of Trott to Roosevelt’s attention and thwarting his mission.

Distrust of Trott and Goerdeler and other members of the resistance who went abroad was increased by the fact that they seemed to their hosts to be shamefully excessive in their expectations. After the onset of the war, the resistance leaders were painfully aware that they could not count on popular support at home, or the cooperation of a significant section of the army, if it seemed that an overthrow of Hitler would be followed by punitive Allied peace terms. They felt it necessary, therefore, to ask the Allies to promise, among other things, that they would not take military advantage of the attentat when it came and that, if it succeeded, the Germans would not be expected to yield all of the territorial gains made by Germany since 1933. The British, who had not, after all, started the war, may perhaps be forgiven for failing to see the logic of this.

An additional difficulty was that the Allies had no accurate information about the size and capacities of the resistance and adopted the position that they could not be expected to supply any form of aid until some credible action showed that it was justifiable. This seemed reasonable enough to neutral observers, like the Chinese revolutionary Lin-Tsiu-Sen, who talked with Trott in Berne in 1942 and told him that the German opposition was too passive. They must take the initiative, he said.

If you can’t kill Hitler, then kill Göring. If you can’t kill Göring, kill Ribbentrop. If you can’t kill Ribbentrop, kill any general in the street.

Trott’s answer, according to Lin-Tsiu-Sen, was, “Germans don’t kill their leaders.”

The resistance movement was, in fact, long on paper and short on action. One cannot read the two books by Von Klemperer and MacDonogh without being astonished by the number of memoranda, special studies, and postwar plans that were constantly being written, circulated among the various resistance groups, and in some cases carried abroad. The Kreisau Circle was a great generator of these, and Carl Goerdeler was still turning them out after the failure of the bomb plot, when he was sitting in prison awaiting death. One is reminded of a passage in the Berlin diaries of Marie Vassiltchikov, the White Russian princess who worked in the Foreign Ministry and had some knowledge of the conspiracy but refused to become involved. In a diary entry of July 19, 1944, she explained why:

The truth is that there is a fundamental difference in outlook between all of them and me: not being German, I have never attached much importance to what happens afterwards. Being patriots, they want to save their country from complete destruction by setting up some interim government; whereas I am concerned only with the elimination of the Devil. Besides, I have never believed that even such an interim government would be acceptable to the Allies, who refuse to distinguish between “good” Germans and “bad.” This, of course, is a fatal mistake on their part and we will probably all pay a heavy price for it.7

The point was well taken. The resistance was perhaps mistaken in not concentrating all along on the salient problem, which was Hitler, and the attempt to “eliminate the devil” came late and was botched. When that happened, “Missy” Vassiltchikov’s friend Trott was one of the nearly five thousand people who were judicially murdered as a result. He had been close to Stauffenberg8 and deeply involved in the plot, and for this he was hanged in the Plötzensee Prison in Berlin on August 26, 1944. In his trial before the People’s Court, Judge Freisler, the “German Vichinsky,” abused him, MacDonogh writes, “as the the sort of spineless intellectual one might find in the Romanisches Café on the Kurfürstendamm [and] attributed his lack of moral fibre to two years at Oxford and two years travelling round the world.”

A final reason for the failure of the foreign policy of the resistance was that, once the war was engaged, the Western Powers were not inclined to complicate things by contacts with a force that stood somewhere between the battle lines. Winston Churchill’s response to a resistance peace feeler in January 1941 was a directive to his foreign secretary, Anthony Eden, that “our attitude towards all such enquiries should be absolute silence.” Eden himself generally ignored messages or proposals from the resistance with the argument, which he used to Bishop George Bell in August 1942, that there was little evidence that a resistance existed, but what really determined his attitude was his desire not to invite criticism from the Russians, to whose views he had shown excessive deference ever since his negotiation of the Anglo-Soviet Treaty of May 1942.9

The unconditional surrender declaration of January 1943, which was also prompted by the desire to propitiate the Soviets, made it even less likely that either Churchill or Roosevelt would soften their attitude toward the resistance. In Germany, the doctrine caused a wave of pessimism in opposition circles. Admiral Canaris, the Abwehr chief, called it “a calamitous mistake” that would prolong the war, adding “our generals will not swallow that,” and Albrecht von Kessel, a member of the resistance stationed in the German consulate-general in Geneva, said that it had “jeopardized, if not destroyed, the work of six years” of active opposition. Trott and Moltke and their colleagues continued to work, through contacts in neutral countries and their friends in the ecumenical movement to get the attention of officials in Britain and America, but it proved to be a losing fight. Von Klemperer writes:

The German Resistance was not able to get a hearing,… not even with the help of the few advocates it could muster abroad, men like A. P. Young, Bishop George Bell of Chichester, Lionel Curtis in Britain, Harry Johansson in Sweden, Willem A. Visser’t Hooft in Switzerland. All were manifestly men of honour and independence, but they, including even Cripps, lacked political clout and thus were unable to help in bridging the widening gap between their German friends’ aspirations and the hard political and strategic requirements of the Grand Alliance. At best the Germans were brought into the orbit of the Allies to serve as informants; but this role they were unwilling to play. They wanted to be recognized as allies of the Powers, and preferably the Western ones, in a common struggle against tyranny and in the building of a new Europe. While the Germans were increasingly ready to subscribe to such high-flown visions, however, the Powers of the Grand Alliance had in the course of the war moved away from them. They settled on the national interest, on considerations defined by power politics, and on winning the war.

There is a certain irony, Von Klemperer points out, in the fact that the Soviets, whom the Western Powers’ antiresistance position was designed to reassure, were, on their own part, quite willing to play with the possibilities of collaboration with the resistance, as they showed after Stalingrad; and both Von Klemperer and MacDonogh intimate that the West may have missed the boat by subordinating planning for the postwar world, in which the resistance may have had a good deal to offer, to their immediate military tasks.

This suggests that the next time someone puts together a book like that of J.C. Squire, he might include as one of the themes “What if, with Allied help, the German Resistance had overthrown Hitler?” In writing an essay on this, one could take either an optimistic or a pessimistic line, arguing in the former case that the result would have been a more tolerable and less dangerous Europe than the one that actually emerged after 1945 and—with much of Eastern Europe possibly free from Soviet control—one more likely to develop into a new European order. Alternatively the case could be made that the profound political differences between the various resistance groups (between the conservative Alte Herren and the followers of Helmuth von Moltke, for example) would have produced a variant of Weimar politics in post-Hitler Germany and made its progress toward democracy slower and more difficult.

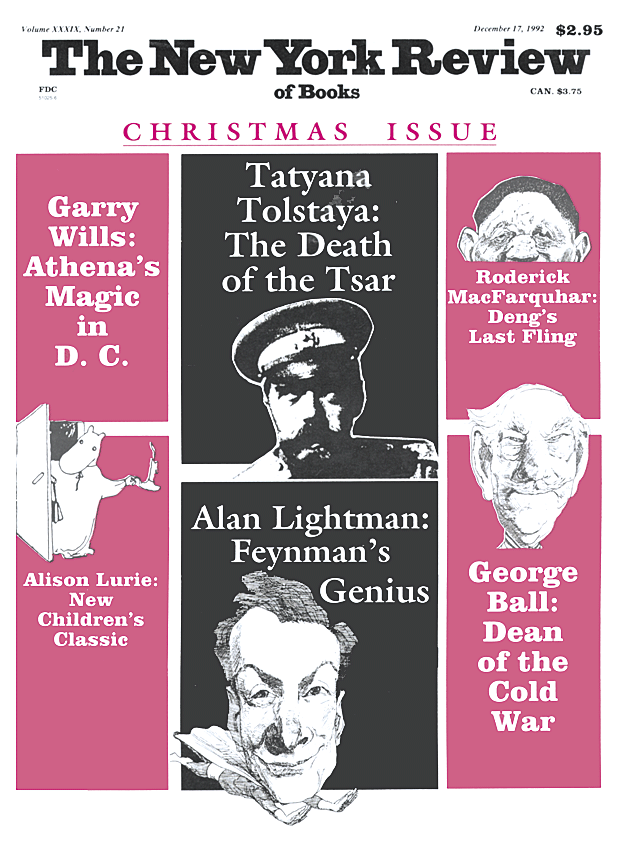

This Issue

December 17, 1992

-

1

If; or, History Rewritten, edited by J. C. Squire (Viking, 1931). ↩

-

2

In both the table of contents and the running heads, this essay is mistakenly entitled, “If Lee had not won the Battle of Gettysburg,” which increases the difficulties of readers who may be already puzzled by the complications of Mr. Churchill’s style. ↩

-

3

The Complete Plays of Gilbert and Sullivan (Norton, 1976), p. 337. ↩

-

4

See R.H.S. Stolfi, Hitler’s Panzers East: World War II Reinterpreted (University of Oklahoma Press, 1992). ↩

-

5

See my articles in The New York Review, “Facing Up to the Nazis,” February 2, 1989, p. 10, and “The Way to the Wall,” June 28, 1990, p. 25. ↩

-

6

A poignant example of this is seen in A Noble Combat: The Letters of Shiela Grant Duff and Adam von Trott zu Solz, 1932–1939, edited by Klemens von Klemperer (Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press, 1988). What they had once called “the best friendship in Europe” did not survive his criticism of her, as he believed, impulsive judgments of Germany and her belief that he was not unsympathetic to German policy in Eastern Europe. See also Gabriele Annan’s review “Living Through the War,” The New York Review, April 9, 1987, p. 7. ↩

-

7

Marie Vassiltchikov, Berlin Diaries, 1940–1945 (Knopf, 1987). ↩

-

8

For details, see the new book by Peter Hoffmann, Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg und seine Bruder (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags Anstalt, 1992). Trott and Stauffenberg became close friends in the spring of 1944. Hoffmann writes (pp. 362ff.): “Trott became Stauffenberg’s ‘foreign policy advisor’ on the central problem of whether a different Germany could reckon on securing a separate peace either in the West or in the East, so as to be free of a two-front war and to be able to meet the remaining adversary with full power.” Stauffenberg seems to have been confident of British assistance, but by the late spring of 1944 Trott, discouraged in this prospect, was trying to make contact with the Russians. ↩

-

9

See my article “Dangerous Liaisons,” The New York Review, March 30, 1989, especially pp. 18–19. ↩