You could describe Margaret Atwood as a Canadian Margaret Drabble, only more optimistic and funnier—or anyway funny more often. Of course such a comparison would be unfair to both novelists, but the temptation to make it is there. Both are witty and serious; both believe that goodness is what matters; both are wickedly skillful at defining characters through their environment and accessories, not just physical, but intellectual as well; both take trouble to work out melodramatic and not always convincing plots; and both produce riveting page-turners for thinking, well-intentioned women.

Atwood is thought of as a feminist writer. In fact, The Robber Bride has been hailed as a break-through exhibiting the latest, improved model of female liberation, with women having the right to be bad; in earlier models they had to be good, badness being reserved for men. Zenia, the robber bride, is bad through and through: a liar, blackmailer, drug pusher, and gratuitous seductress. She seduces the men belonging to the three women who take turns at being the focus of the story. Tony, Charis, and Roz—like Esther, Alix, and Liz in Drabble’s The Radiant Way—can be read to represent mind, soul, and body, respectively.

Tony is an under-sized military historian; she teaches at the university in Toronto, where the story is set. Her casseroles come from the 1960 edition of the Joy of Cooking and she wears childish Peter Pan collars. In her basement she has a relief map of Europe, on which, at the start of the book, she is reenacting the defeat of Otto II, the tenth-century Holy Roman Emperor. She has put “cloves for the Germanic tribes, red peppercorns for the Vikings, green peppercorns for the Saracenes, white ones for the Slavs. The Celts are coriander seeds,” and so on. Upstairs Tony has West, a wimpish musicologist who has never quite recovered from his affair with Zenia. Zenia stole him from Tony many years ago, got tired of him, and threw him out (this is her pattern). West crept back to Tony. They got married, but the marriage is not passionate: more a matter of holding hands for comfort. Neither is sexually attractive; both know it.

Goofy Charis lives alone in a ramshackle cottage on an island in Lake Ontario. She worries about people’s auras and her own electrical field, and works in a shop called Radiance, selling crystals, seashells, incense, organic body oils, Oriental jewelry, tapes of New Age music, and books on “Health Secrets of the Aztecs.” Another of Atwood’s needlesharp, ironic, and affectionate lists. At the time of the Vietnam War, Charis shelters an American draft dodger, or so she thinks. Billy is actually wanted for drug running (in a small way). Zenia steals him from Charis, uses him as a runner in her own drug dealing affairs, and sheds him as she shed West. Charis is left to have his baby, who grows up to be a hard-edged girl with yuppie ambitions and a hard-edged haircut in savage contrast to her wispy, woolly mother. After Billy, Charis forswears sex.

Roz alone of the three heroines likes it. She is fat, noisy, funny, rich, a mother hen and successful business woman. Her father was a charming immigrant Jewish crook and her mother a dour Canadian. Roz is new money and marries old money in the shape of Mitch. Mitch doesn’t actually have much (which is why he marries Roz), but he is classy and sexy. Roz makes him a partner in the property company she inherits from her father, and has him on the board of the feminist magazine she bankrolls. She puts up with his womanizing, partly because he’s so attractive, partly for the sake of their son, Larry, and their twin daughters. His walk-outs are afternoon or weekend affairs until Zenia knocks him off his feet. Then he moves out and sets up with her in a ritzy apartment overlooking the marina where he keeps his sailboat. When his turn comes to be thrown out, Roz refuses to have him back. He drifts, drinks, and finally drowns; suicide, probably.

The three betrayals are told in serial flashback, and another round of flash-backs throws up the early biographies of the three betrayed women: orphaned, neglected, homeless, unloved, cheated, abused, they all have childhood case histories straight from the Living sections of the Sunday supplements (which Atwood satirized in her previous novel, Cat’s Eye). Even Mitch’s father turns out to have committed suicide, which helps to even up the distribution of traumas between the sexes.

The novel is explicitly not anti-man. The problem-page material is updated on page 450 (out of 466) when Roz discovers that, far from laying Zenia as she suspects and fears, twenty-two-year-old Larry is having a homosexual affair with her own endearing personal assistant Boyce. “You’re not losing a son, you’re gaining a son,” says the irrepressible Boyce. So Roz agrees to decorate the boys’ new apartment. Homosexuality does not preclude happy families, a message also encoded in Ang Lee’s recent film The Wedding Banquet. Atwood has nothing new to say either about tolerance or feminism, but her story does take notice of the development of both, from the late Fifties, when her heroines were children, to the present. Musing along with Roz, she writes,

Advertisement

According to the feminists, the ones in the overalls, in the early years, the only good man was a dead man, or better still none at all; yet Roz continues to wish her friends joy of them, these men who are supposed to be so bad for you. I met someone, a friend tells her, and Roz shrieks with genuine pleasure. Maybe that’s because a good man is hard to find, so it’s a real occasion when anyone actually finds one. But it’s difficult, it’s almost impossible, because nobody seems to know anymore what “a good man” is. Not even men.

Or maybe it’s because so many of the good men have been eaten, by man-eaters like Zenia.

Tony, for her part, notices how strong the younger generation of women is compared to her own. “They have none of the timidity that used to be so built-in, for women. She hopes they will gallop through the world in style, more style than she herself has been able to scrape together.” Besides pinpointing the state of feminism in 1993, these two passages illustrate the niceness and generosity of Roz and Tony; Charis, of course, is not only nice but soft as well.

Still, the title of the book tells us it’s the man-eater we should be interested in. Atwood adapted it from a Grimm’s fairy tale called “The Robber Bridegroom,” in which a young bride outwits a murdered who lures young women to his den and cuts them up. Atwood has already published a poem called “The Robber Bridegroom,” written from the homicidal bridegroom’s point of view and describing what it feels like to be a male sexual sadist. The Robber Bride makes us privy to everything that goes through the heads of Tony, Roz, and Charis, but doesn’t say anything about what it feels like to be Zenia. She is as opaque as the robber bridegroom in the original fairy tale. She has a repertoire of alternative deprived childhoods, all invented, with which she curries sympathy, not to speak of other faked afflictions like cancer. She even fakes her own death and funeral—the occasion on which Roz, Tony, and Charis meet for the first time since they knew Zenia at college.

Five years later Zenia appears like a revenant in the restaurant where they have taken to meeting for lunch. She has returned to Toronto in order to con all three of them all over again. But this time they reject her, and she finishes up dead in the fountain under her hotel balcony. Murder, suicide, or drug-induced accident? The autopsy reveals terminal ovarian cancer to boot, and the whole episode is such a bare-faced parody of conventional thriller endings that the message you get is that the denouement is not the point of the novel.

The last chapter is a sort of epilogue. Tony, Roz, and Charis meet to scatter Zenia’s ashes into Lake Ontario.

Every ending is arbitrary, because the end is where you write The end. A period, a dot of punctuation, a point of stasis. A pinprick in the paper: you could put your eye to it and see through, to the other side, to the beginning of something else…. An ending, then. November 11, 1991, at eleven o’clock in the morning, the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month. It’s Monday, the Recession is thickening, there are rumors of big-company bankruptcies, famine is rolling over Africa; in what was once Yugoslavia there is ethnic feuding. Atrocities multiply, leaderships teeter, car factories grind to a halt. The war in the Gulf is over and the sands are spackled with bombs; the oil fields still burn, clouds of black smoke rolling out over the greasy sea. Both sides claim to have won, both sides have lost. It’s a dim day, wreathed in mist.

This kind of gloomy, incantatory historical run-down is a cliché. Drabble uses it too, but at least her plots are explicitly linked to world events. The telling thing about Atwood’s ending is that as Zenia is finally laid to rest, Tony admits to herself that she admires her courage; Roz admits feeling gratitude towards her; and Charis, when the clay receptacle with the ashes accidentally breaks as she is about to throw it in the water, believes she sees “a slight blue tinge, a flickering…. It was her.” So are we witnessing a celebration of female wickedness by three good women—an up-dated Manichean rite? Are we to spot an esoteric clue in Tony’s sand table a few pages back, when it was set for the siege of Lavaur in 1211? “The besieging Catholics are represented by kidney beans, the defending Cathars by grains of white rice.” The Cathars were Manicheans; the Catholics slaughtered them, and Tony tries to empathize with Dame Giraude, the Cathar woman commander of Lavaur:

Advertisement

Did she despair, was she praying for a miracle, was she proud of herself for having fought for what she believed in? Watching her co-religionists fry the next day, she must have felt that there was more evidence in support of her own theories of evil than of de Montfort’s.

The novel ends on a philosophical note, with Tony thinking of Zenia as an eternal woman—not the gentle, redemptory Marian aspect of ewiges weibliches Goethe has in mind, but its witch-like alter ego: “an ancient statuette dug up from a Minoan palace; there are the large breasts [implants, in Zenia’s case]…the dark eyes, the snaky hair…. Was she in any way like us? Are we in any way like her?” The answer is obvious.

Too obvious. The Robber Bride is ultimately a soap opera for moderate feminists. It goes at a great clip; funny, full of verve, with gripping incidents in sociologically witty settings and lively, engaging characters observed with irony and affection (Roz’s teen-age twin daughters are particularly fetching). The narrative is in the third person, but the idiom alters amusingly as the focus changes from character to character, so that it’s like listening to a clever impersonator performing. There are schlocky bits, like this one: “Guilt descends, billowing softly like a huge grey parachute, riderless, the harness empty. Her gold wedding ring weighs heavy as lead on her hand.” But then, this is Roz, so perhaps we’re meant to see her impregnated with the kind of stuff she might print in her magazine. The depressing thing is that Atwood seems to assume that all her readers will be impregnated with it, too.

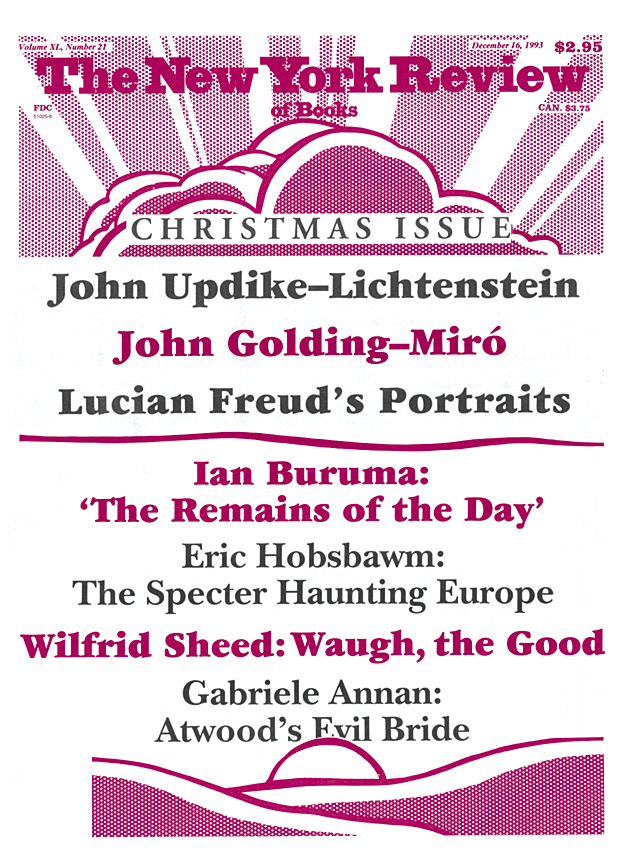

This Issue

December 16, 1993