Under an unknown picture somewhere in India there is hidden a portrait of Salman Rushdie’s mother. The story goes like this. An artist, hired by Rushdie’s father to paint Disney animals on the walls of the child Salman’s nursery, went on to do a portrait of Mrs. Rushdie. When the painting was finished, Rushdie père did not like it. The artist stored the picture in the studio of a friend of his, another artist, who, running out of canvases one day, painted a picture of his own over it. Afterward, when both had become famous artists, the friend could not remember which picture he had painted over the other’s canvas, or to whom he had sold it.

When Rushdie told me the story recently when I was interviewing him for the Irish Times it struck me as peculiarly apt, given both the kind of artist Salman Rushdie is (the painted mother, the harsh father, the Disney creatures poking their anthropomorphic noses through the backdrop) and his present circumstances. He too has disappeared behind a work of art.

We met in the stillness of a post-Christmas bank holiday afternoon. I had not seen him for ten years. He had changed. How would he not? Yet the differences in him were a surprise. I had expected that he would be angry, tense, volubly outraged. However, what I sensed most strongly in him was an immense and somehow sustaining sadness. The confident, exuberant, funny thirty-five-year-old I met ten years ago had taken on a gravitas that was at once moving and impressive.

On February 14 Rushdie will have been in hiding for four years. The fatwa, or death sentence, imposed on him by Ayatollah Khomeini in retribution for his “blasphemous” novel The Satanic Verses, is still in force, backed up by the offer of $2 million in blood money to anyone who should be successful in murdering him. Over the years the world has accommodated itself to this extraordinary situation, but nevertheless it is, as Rushdie himself insists, a scandal.

I began by asking if he could discern any shift in the political situation in Iran that would give him hope that the fatwa might be lifted.

“I used to spend a lot of my time trying to keep up with the internal struggles there, but then I thought, to hell with that. It’s not my business to understand the internal politics of Iran. The banning of my book and the imposition of the fatwa is a terrorist act by the state of Iran, and my business is simply to make sure that the Iranian state is dealt with on that basis, and is obliged to alter its position.”

Does he have any contact with people in Iran—people in power? “There have been occasions when so-called intermediaries have popped up out of the woodwork, claiming to have great contacts in Iran. What tends to happen is that I talk to them for a couple of weeks and then they disappear and I never hear from them again.

“The question all these people ask is, What reparations would I be prepared to make? But my view is, who is injuring whom here? It’s not for me to say I will withdraw The Satanic Verses. The whole issue is that a crime has been committed against the book.”

How did the book come to the attention of the mullahs in the first place?

“Well, I think…” A hesitation, and a low chuckle; his delight in the rich absurdity of human affairs is one thing that has not changed over the years. “…I think it started in Leicester.”

So I have my headline: It Started in Leicester.

“It does seem the first rumblings against the book started in a mosque or council of mosques there. They circulated selected lines and passages from the book to show how terrible it was. From there, it spread around Britain and out to India and Pakistan and Bangladesh, where there were riots and people were killed.” There are a number of legends about how the book came to Khomeini’s attention. There is a passage in the novel about an Imam in exile who is not unlike Khomeini, and there is a view that he took exception to it. “I don’t find that very convincing because the book did not exist in a Farsi edition, and there were no copies of the book available in Iran at that time anyway. It’s since been admitted by quite high-ranking Iranian officials that Khomeini never saw a copy of the book; whatever he did he did on the basis of hearsay.”

I ask the only question I have come prepared with: Does he feel the affair has made him into a purely political phenomenon?

“One of the oddest things for me about the business is that while Mid-night’s Children and Shame were in some ways quite directly political, or at least they used history as part of their architecture, I thought The Satanic Verses was the least political novel I had ever written, a novel whose engine was not public affairs but other kinds of more personal and cultural crises. It was a book written really to make sense of what had happened to me, which was the move from one part of the world to another and what that does to the various aspects of one’s being-in-the-world. But there I am thinking I’m writing my most personal novel and I end up writing this political bombshell!

Advertisement

“Certainly it is a big problem that people by and large don’t talk to me about my writing. Even the novel I wrote after The Satanic Verses [Haroun and the Sea of Stories], which was a great pleasure for me, and which individual readers responded to warmly, was received on the public level as if it were something to be decoded, an allegory of my predicament. But it’s not an allegory; it’s a novel.

“All the same I can’t avoid the situation; while I don’t see myself as this entity that has been constructed with my name on it, at the same time I can’t deny my life: this is what has happened to me. It will of course to some extent affect my writing, not directly perhaps but yet in profound ways. I have always to some extent felt unhoused. I feel very much more so now.”

Is this not a good, a necessary way for an artist to feel?

“We are all in some manner alone on the planet, beyond the community or the language or whatever; we are poor, bare creatures; it’s no bad thing to be forced to recognize these things.”

An irony of the affair not much remarked on is that The Satanic Verses is very sympathetic and tender toward the unhoused, the dispossessed, the deracinated—the very people, in fact, who rioted in the streets and publicly burned what they had been told was a blasphemous book. He nods, smiling, in a kind of hopeless misery. It is deeply painful for him that the people whom he has made his subject, and for whom he has a deep fondness, are the ones who hate him most, or hate at least that image of him fostered by fanatics in the Muslim world.

He is adamant that what is most important here is the integrity of the text. “When at the start of the affair I was able to contact friends and allies and they asked me what I wanted them to do, I said, Defend the text. Simply to make a general defense of free speech doesn’t answer the attack; the attack is particularized. If you answer a particularized attack with only a general defense then to some extent you are conceding a point, you’re saying, Oh yes, we recognize that it may be an evil book, but even an evil book must be allowed to exist. But it is not an evil book. So I have always been most grateful when people have tried to defend the text, for that’s at least as important to me as the defense of my life.”

What interests me in Rushdie’s fiction—in anyone’s fiction—is not its public, political aspect, but the way in which in it the objective world is reordered under the pressure of a subjective sensibility. It struck me, re-reading The Satanic Verses in preparation for this meeting, that the final section, a (relatively) realistic account of a father’s death, is perhaps the most significant—and certainly the most moving—passage in the book, the moment toward which the whole work moves, no matter how fantastical what went before. Was this section grounded in personal experience?

“Very much. My father died of the same cancer that killed the character in the book. I was there when he died. He and I had always had a somewhat difficult relationship, and it was important for us to have some time together before the end. I felt a great moral ambiguity about using my father’s death in that way, especially as it was so recent, but in the end I thought I would do it because it would be an act of respect. I was afraid that it might appear a stuck-on ending, but as it turned out it seemed to be just what the book needed, had been demanding.”

He believes that one of the most important themes in the novel is loss: of parents, country, self, things which to a greater or lesser degree Rushdie himself has lost. Does he feel abandoned by those in the Muslim world who he might have thought would support him?

Advertisement

“Intellectuals in the Muslim community know the size of the crime that has been committed against the book. A few months ago a declaration of unequivocal support for me was signed by seventy or so leading Iranian intellectuals in exile, which was wonderfully courageous; after all, they are not receiving government protection, and in some cases, as a result of their support for me, their lives have been threatened by the Iranians.*

“An important part of their statement was that blasphemy cannot be used as a limiting point on thought. If we go back to a world in which religious authorities can set the limits of what it is permissible to say and think, then we shall have reinvented the Inquisition and de-invented the whole modern idea of freedom of speech, which was invented as a struggle against the Church.”

We turn to the subject of the book he is working on. “It’s about someone who is thrown out of his family because of an unfortunate love affair. It begins with this expulsion from the family, and goes on to recount how he is forced to remake his life from scratch.” We are back to the feeling of homelessness that weighs so heavily upon him.

He tells me the story of the lost portrait of his mother. “In my book, about a very different mother and a very different son, there is a similarly lost portrait, and one of the strands of the story is his finding this picture, and in this way the struggle there had been in life between mother and son continues beyond death.”

The novel will be called The Moor’s Last Sigh, which is a translation of the Spanish name of the place from which in 1492 the last Sultan of Granada, driven out of the city by the Catholic armies of Ferdinand and Isabella, looked back for a final time at the Alhambra palace.

“The idea of the fall of Granada is used throughout the book as a metaphor for various kinds of rupture. One can see Moorish Spain as a fusion of cultures—Spanish, Moorish, Jewish, the ‘Peoples of the Book’—which came apart at the fall of Granada.

“This was the only time in history when there was a fusion of those three cultures. Of course, one should not sentimentalize that entity, for the basis on which it existed was Islamic imperialism; Islam was clearly the boss, and the other religions had to abide by the laws. All the same, there was a fusion of cultures which since then have been to some extent each other’s other. In that fusion are ideas which have always appealed to me, particularly now; for instance, the idea of the fundamentalist, totalized explanation of the world as opposed to the complex, relativist, hybrid vision of things.”

The last sultan, Boabdil (Muhammad XI, d. 1527), was “weak,” that is, he was a “poetic type”—“which means, I suppose, he was someone in whom all the cultures flowed and therefore was unable to take absolutist views; against him there was the absolutist Catholic Queen Isabella, and his own formidable mother, Aisha. As Boabdil paused on that last ridge, Aisha is reputed to have told him, ‘Yes, you may well weep like a woman for what you could not defend like a man.’

“The story is a metaphor for the conflict between the one and the many, between the pure and the impure, the sacred and the profane, and as such is a continuation by other means of the concerns of my previous books. Boabdil’s story is merely background—there is no direct ‘historical’ narrative—and is done rather like Sidney Nolan’s series of Ned Kelly paintings.

“The book is grounded in my experiences of these past years, and what makes it particularly interesting for me is that this is true, not fiction; that this obscene thing could happen to me and my book, and could go on and cease to seem scandalous.”

Rushdie feels that the reaction to the book was in part a result of the force of the political language of Iran. The Iranians saw the United States as the Great Satan, and Britain, a satellite of the US, as a Little Satan, whereas the Jews were seen as being responsible for everything that is wrong in the world. “So when, in the mullahs’ view, a Jewish American publisher hired a self-hating race-traitor and (British) wog to write a book to attack Islam, the ‘conspiracy’ was complete.

“The thing I didn’t understand—or underestimated the force of—was that whereas in the Judeo-Christian tradition it is accepted that one may at least dispute whether good and evil are external or internal to us—to ask, for instance, Do we need such beings as God and the Devil in order to understand good and evil?—the parts of my book that raised this question represented something that it is still very hard to say publicly in the Islamic world; and to hear it said with all the paraphernalia of contemporary fiction was very upsetting for many people, to which I’m afraid my only answer is, That’s tough—because this kind of thing needs to be said.”

He was looking forward to going to Ireland, believing that in such a country, with its recent memories of colonialism, and which is still to some extent engaged in nation-building, it would be easier for him to be understood than in many other, more “progressive,” countries. “Also, the knowledge that people have who live in countries where God is not dead is very different to that of people who live in countries where religion has died.

“I have always insisted that what happened to me is only the best-known case among fairly widespread, coherent attempts to repress all progressive voices, not just in Iran but throughout the Muslim world. Always the arguments used against these people are the same: always it’s insult, offense, blasphemy, heresy—the language of the Inquisition. And you can widen your view and look for the same process beyond the Muslim world, where the same battle is continuing, the battle between the sacred and the profane. And in that war I’m on the side of the profane.”

I ask, with some hesitation, if he would like to say something about his public declaration, two years ago, of his espousal of Islam, which he subsequently recanted. He flinched, as at the resurgence of an old pain.

“I feel I’ve had to undo that; I’ll probably be saying that for the rest of my life.

“What happened was this. First of all, I was probably more despairing in that moment than I’ve ever been. I felt that there was no energy or enthusiasm in the world to do anything about my plight. Secondly, a thing which people sometimes don’t understand is how painful it was for me to realize that the people I had always written about were the very people who were now burning the book. The need in me to heal that rift was very profound—still is.

“Those two things came together—the despair, and the need to heal the rift—and what I felt was, look, I’d better do something very large in order to show these people whom I write about that I’m not their enemy; that, yes, I do have a very profound dispute with the way in which the people who are in power in Islam attempt to regulate their societies, but that maybe in the end I could carry on that dispute more effectively from inside the room than from outside it. I wanted to say, I am not outside the house of Islam throwing stones at the windows, I’m inside it trying to build it and redecorate it. That was the way I thought about it to myself at the time, but also I can see that in that process there was a large effort to rationalize the doing of something I thought might help.

“All I can say is that, having said what I said I felt sick with myself, for a very long time, not because so many people who had been supporting me found it bizarre or whatever—because my response to that was then, and remains today, that anyone who thinks he can do better is welcome to come and try.

“The problem for me was not other people’s attitudes; the problem for me was my own sense of having betrayed myself.

“The issue was that the thing that has enabled me to survive in this affair has been that I have always been able to defend my words and writings and statements; always I said what I said and wrote what I wrote because it was what I felt, because it was what came out of me truthfully, and as a result I could stand by it; but as that moment I felt I had done something that I couldn’t defend in that way, that did not represent my real feeling.

“There were good reasons for it—the attempt at peacemaking and so on—but it was not a statement I could put my hand on my heart and say I believed in.

“I found it agonizing that my public statements were at complete odds with my private feelings. That situation became untenable for me, and so I had to unsay it; and now I’ve been unsaying it for two years. I’ll probably have to unsay it to the press in every country in the world.

“After what religion has done to me in the last four years, I feel much angrier about what it does to people and their lives than I ever did before; that’s the truth. The writer who wrote The Satanic Verses was sympathetic to Islam, was trying very hard to imagine himself into that frame of mind, albeit from a nonbelieving point of view; I couldn’t write that sympathetically now, because of the very intimate demonstration I have had of the power of religion for evil; that is now my experience, and for me to try to write from some other experience would be false.

“I can still accept at a theoretical level the power of religion for good, the way in which it gives people consolation and the way in which it strengthens people, and the fact that these are very beautiful stories and that they are codifications of human belief and human philosophy, I wouldn’t deny any of that—but in my life religion has acted in a very malign way, and in consequence my reactions to it are what you would expect.”

I suggest that in the matter of his “conversion” he is likely to be harder on himself than anyone else would be. A great many people do things which they come to be ashamed of, but these actions will never get into the headlines.

“Of course, that’s true. Martin Amis very soon after the fatwa was imposed said I had ‘vanished into the front page,’ and I think that it was a very accurate phrase. I have been trying to escape from the front page. “What I find now is that the ideas that present themselves as things I want to write about are much less public, much less politically generated than they used to be. I have now had enough politics to last a lifetime. I now want to write about other things.”

Have circumstances got easier for him, or has he got used, insofar as one can get used, to the kind of life he has been forced to lead?

“They’ve got easier and more difficult. At the beginning, the first eighteen months, it was very hard for me to emerge from the safe place; it was a very sequestered time.” In those early days did he have a garden, somewhere outside, where he could walk?

“Depends where I was; often, no. We had to be very careful because we had no knowledge of what was coming against us. It was a personally difficult time because of my marriage ending. That was the worst time, in terms of physical constraints. It’s got a little easier now, even though it does still involve incredible paraphernalia, all this cloak and dagger stuff, but I’m not quite as confined as I was.

“On the other hand, psychologically I find it harder to tolerate now than I did then. When this began, nobody expected it to last very long. I remember the first day when the police came to offer me protection, they said, Let’s just go away and lie low for a few days while the governments sort it out. People thought because what had happened was so outrageous it would have to be fixed and would be fixed very soon. This was why I agreed to dive underground, because everyone thought it would be just a matter or days. And here we are almost four years later.

“When it began I could say to myself, It’s an emergency, and in such a case you do what is necessary to handle it, so I could accept the need for hiding, etc. Now, four years later, I realize it’s not an emergency, it’s a scandal. And what’s worst about it is that people are behaving as if it were not a scandal.”

Does he feel the British government is not doing enough?

“Well, let’s face it, they saved my life. They are affording me in, I must say, a very ungrudging way, a level of protection that is equivalent to what the Prime Minister would get, and I’m just some novelist. To that extent they’ve done a great thing for me. But if we are to get to a position where none of this is needed, it’s going to require not just a defensive act, but a positive act.

“As a result of the trips abroad I’ve been able to make there is a lot of interest in Europe and North America in doing something about the case. And I’m trying to make the government here see that this would be a wonderful moment for it to put itself at the head of that international effort.”

Has he met John Major?

“No. I hope that might be rectified. It’s a problem. This campaign requires practical acts and symbolic gestures. At that level, the fact the British Prime Minister has never allowed himself to be seen in public shaking my hand is an indication that the affair is being in some way downgraded. It’s getting to the point where it’s easier for me to meet the heads of other governments than the leaders of my own.

“Things are moving, however. The British government have now formally told the Iranians they will not normalize relations until the fatwa is canceled. Also, at the recent Edinburgh Summit the British delegation introduced into the conclusions of the summit a statement that all European nations should continue to pressurize Iran on the fatwa.”

Was he very frightened at the start? Is he less frightened now?

“It’s less now because the situation is less frightening. At first it wasn’t a matter really of being frightened. When I first heard the news I thought I was dead. I thought I probably had two or three days at the most to live. That’s beyond fear, it was the strangest thing I’ve ever felt.

“After that it was very shocking and unnerving to see the extent of the hatred that was being hurled at me; that was very disorienting, very bewildering. Then I came to the conclusion that I must not allow myself to be terrified; the only answer to a terrorist is to say, I’m not scared of you. That was an extraordinary moment. I felt free.”

Has the experience of the past four years changed him?

“Yes, it’s changed me very much. It has hurt me a great deal. If you are on the receiving end of a great injury you are never the same again; you may not be worse, you may not be better, but you’re never the same again. It made me feel everything I thought I knew was false. I was always very impatient—with the exception of writing, where I’m very patient—but now I’m able to take a longer view of things.”

The experience must have affected the quality of his life, must have thinned it out. His reply is simple.

“My life has been wrecked.”

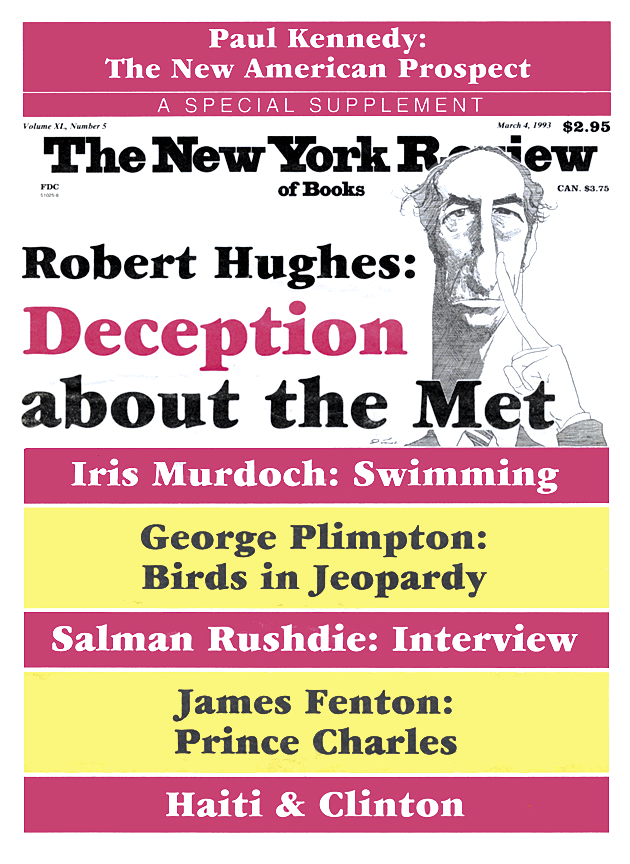

This Issue

March 4, 1993

-

*

“A Declaration of Iranian Intellectuals and Artists in Defense of Salman Rushdie,” printed in The New York Review, May 14, 1992, p. 31. ↩