Between 1982 and 1986, Bogdan Bogdanović, an architect, was the mayor of Belgrade, where he now lives.

Much as I ponder the abnormalities of our current civil war, I cannot comprehend why military strategy should make the destruction of cities a main—if not the main—goal. Sooner or later the civilized world will dismiss our internecine butchery with a shrug of the shoulders. How else can it react? But it will never forget the way we destroyed our cities. We—we Serbs—shall be remembered as despoilers of cities, latter-day Huns. The horror felt by the West is understandable: for centuries it has linked the concepts “city” and “civilization,” associating them even on an etymological level. It therefore has no choice but to view the destruction of cities as flagrant, wanton opposition to the highest values of civilization.

What makes the situation even more monstrous is that the cities involved are beautiful, magnificent cities: Osijek, Vukovar, Zadar, with Mostar and Sarajevo waiting their turn. The strike on Dubrovnik—I shudder to say it, but say it I must—was intentionally aimed at an object of extraordinary, even symbolic beauty. It was the attack of a madman who throws acid in a beautiful woman’s face and promises her a beautiful face in return. That it was not the work of a savage’s unconscious ravings, however, is clear from the current plan to rebuild Baroque Vukovar in a nonexistent Serbo-Byzantine style, an architectural fraud if there ever was one and a sign of highly questionable motives.

Were our theologians a bit more imaginative I might interpret their vision of a Serbo-Byzantine Vukovar to be the parable of a heavenly city coming to earth as a temporary, tangible sign of the heavenly Serbia to come. But if we take a more prosaic look at the idea of forcing the willfully destroyed Vukovar to change its face, we see it as no more than a wild military fantasy, like the one of razing Warsaw’s Old Town and erecting a new Teutonic Warsaw from the ashes.

For years I had been developing the thesis that one of the moving forces behind the rise and fall of civilizations is the eternal Manichaean—yes, Manichaean—battle between city lovers and city haters, a battle waged in every nation, every culture, every individual. It had become an obsession with me. My students enjoyed hearing me go on about it, but also smiled at one another as if to say, “He’s at it again.” Then came the moment when I realized to my horror that “it” was our day-to-day reality.

Together with ritual murder as such I see the ritual murder of the city. And I see murderers of the city in the flesh. How well they illustrate the tales I told in the lecture hall, tales of the good shepherd and the evil city, of Sodom and Gomorrah, of the walls of Jericho tumbling down and the wiles of Epeios and his Trojan Horse, of the Koran’s curse: that all cities of this world shall be destroyed and their wayward inhabitants transformed into monkeys. Today’s grand masters of destruction take pleasure in expounding their motives; they take pride in them. After all, from time immemorial cities have been razed in the name of the purest of convictions, the highest, strictest moral, religious, class, and racial criteria.

City despisers and city destroyers haunt more than our books; they haunt our lives. From what depths of a misguided national spirit do they rise and where are they headed? On what muddled principles do they base their views? By what images are they obsessed and in what morbid books do they find them? Clearly in books that have nothing to do with history. For the savage has trouble grasping that anything could have existed before him; his idea of cause and effect is primitive, monolithic, especially when it takes shape during coffee-house confabulations.

The phenomena I am trying to describe may in the end defy description. I therefore ask my readers to accept these thoughts as a bleak attempt to combine cognition and intuition and get at the roots of the savage’s ancient, archetypal fear of the city. But while in ancient times that fear was a “holy fear” and therefore subject to regulation and restraint, today it represents the unbridled demands of the basest mentality. What I sense deep in the city destroyers’ panic-ridden souls is a malicious animus against everything urban, everything urbane, that is, against a complex semantic cluster that includes spirituality, morality, language, taste, and style. From the fourteenth century onward the word “urbanity” in most European languages has stood for dignity, sophistication, the unity of thought and word, word and feeling, feeling and action. People who cannot meet its demands find it easier to do away with it altogether.

Advertisement

The fates of Vukovar, Mostar, and Sarajevo’s Baš-caršija—the old Turkish center of the town—bode ill for the future of Belgrade. No, I do not fear foreign hordes beneath the walls of Kalemegdan,* sad to say, what I fear are our home-grown masters of destruction. Cities fall not only physically, as a result of outside pressure; they fall spiritually, from within. The latter is in fact the more common variant. The new conquerors will make us recognize them at gunpoint. Accustomed as Balkan history is to mass migrations, the danger is clear. The National Liberation movement at the end of World War II was at least in part a mass migration, a gunpoint migration of the rural populace to the city, a kind of forced urbanization. Many people still recall the devastating consequences of that “invigorating renewal of our cities,” and a similar scenario is not hard to imagine today.

If the brave defenders of Serb villages and the abortive conquerors of Croat towns do in fact force us to recognize them as fellow citizens, if they move in and take over, we know what to expect. The partisans condemned the decadence of the city and promised its social regeneration: the new Nazi-Partisans promise to cleanse our Serb Sodom and Gomorrah of all national renegades. Once again cities are being destroyed in the name of the highest, the most noble goals. Before long someone will surely decide that Belgrade too could do with a bit of ethnic cleansing, and a theory for momentous national undertakings of the sort—provided our new Kulturträger [cultural elite] feel the need for one—can always be found. For did not the great father of our nation, Vuk Karadzić, who codified the Serb language in the nineteenth century, teach us that Serbs prefer not to live in cities, those agglomerations of Wallachians and Germans and suchlike cosmopolitan riffraff?

And if they proclaim us weaklings, relics, insufficiently Serb, if they decide our cities are in need of racial and national regeneration, then any of us they fail to scare away (and they are doing their best to terrify us now), they will—following Holy writ—turn into monkeys.

Which is why when I hear people talk about the New Serbia my main concerns are how to preserve the scrap of urbanity left to us and how to prevent them from making monkeys of us.

—Translated from the Serbian by Michael Henry Heim

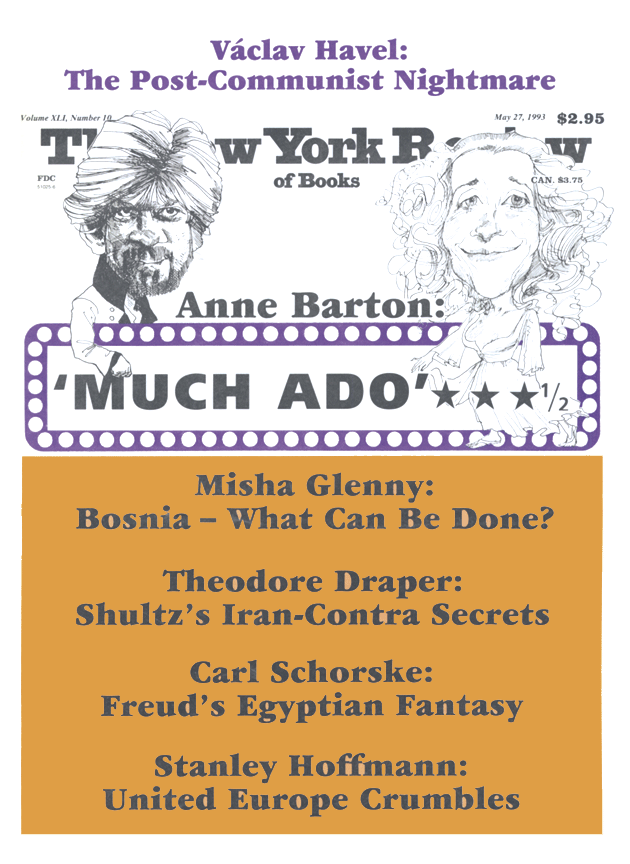

This Issue

May 27, 1993

-

*

the Turkish fortress overlooking Belgrade. ↩