The world doesn’t seem to appreciate what is at stake in Bosnia. We are aware of the human suffering, we are outraged at the atrocities, we are humiliated by the inability of both the United Nations and the European Community to prevent violence. But we do not quite understand the implications of our failure to intervene militarily. If we did, we would have intervened long ago.

What is happening in Bosnia demonstrates, once again, that borders can be changed by force and that this will be accepted internationally as a fait accompli. Of course there is nothing new in this. It only shows all the more clearly that we have not succeeded in establishing a new world order capable of upholding the rule of law, of protecting human rights and resolving conflicts peacefully.

Events in Bosnia have also shown that there is hardly any limit to the brutality that can be employed in the service of a national goal; indeed, that brutality against a civilian population is an effective instrument of national policy. That is a much graver matter. Brutality has always existed but continuing to tolerate it after it has been exposed can only weaken future attempts to resist it.

The unspeakable brutality that we have witnessed in Bosnia is not simply the byproduct of mindless aggression; it has been committed in the name of a doctrine, the doctrine of the ethnic state. That is where the danger lies. Ethnic states leave no room for people with different ethnic identities, and “ethnic cleansing” can turn ethnic identity into a matter of life and death. If it prevails in the many parts of the world which are susceptible to it, our entire civilization could be endangered. I realize these are large statements, but I believe they are justified.

This is not the first time that civilization has been threatened by a doctrine. Communism posed such a threat and, before that, National Socialism. Indeed, almost any doctrine can become a threat to civilization if it is taken seriously enough, and if it can gather sufficient force. In the Middle Ages, people went to war over the doctrine of transubstantiation.

A sense of ethnic identity has been a powerful force throughout history, and has played an important part in the formation of the modern state. As a historical force it has been rivaled only by religion, especially if we include communism as a secular religion. There is nothing inherently evil in having a sense of ethnic identity. On the contrary, it is an important element in holding a nation together, and the coexistence of a great many different nations, languages, and cultures has given civilization the diversity it needs to be productive and creative. But when ethnic identity is turned into a doctrine of exclusion it becomes harmful. When it is used as the criterion of citizenship it infringes on human rights; and when it is used as a justification for destroying rival ethnic groups it becomes a danger to civilization itself. That is what has happened in Bosnia.

The West has been surprisingly complacent. Public opinion has been aroused from time to time by pictures of atrocities and stories about the suffering of civilians, but governments have gone out of their way to defuse public concern and, on the whole, they have been remarkably successful. The Balkans have been portrayed as a kind of hell in which ethnic conflicts are endemic, a place to stay away from if at all possible. One can engage in humanitarian relief and attempt to solve the conflict by diplomacy, but one should avoid taking sides because all sides are to blame.

This is the message the public has been receiving, but the politicians, the State Department, and the British Foreign Office ought to have known better. Indeed, four US foreign service officers have resigned in protest. The British, for their part, are probably influenced by the continuing impasse in Northern Ireland and by their memories of what happened in Yugoslavia during the Second World War. The Clinton administration has tried to have it both ways: it has responded to reports of atrocities by raising the prospect of military action but then backed away when the pressure abated. Although analogies to Munich have been overused, this is the occasion when both Europe and the United States ought to recall what took place there.

The Munich agreement meant both the appeasement of an aggressor and a failure of political will on the part of the democratic nations, and it was the prelude to something much more serious and much more painful. Of course Milosevic is not Hitler and a Greater Serbia does not pose the same threat as Nazi Germany did. Still, the similarities are disturbing. Hitler laid down his program in Mein Kampf: Milošević adopted a blueprint for a Greater Serbia which was drawn up in 1986 in a “memorandum” of the Serbian Academy of Arts and Sciences. The principle Milošević stands for can spread and conditions are particularly propitious for it.

Advertisement

Communism was a universal closed system that failed and cannot be revived. It was based on a universally applicable doctrine and administered by a Party dictatorship which suppressed any competing ideas that might arise from below or penetrate from the outside. The doctrine has been discredited, but the memory of totalitarian rule and the cast of mind that made it possible are very much alive. Unless specific action is taken to prevent it, the universal closed society based on communism is likely to break down into particular closed societies along national or ethnic lines.

A leader who wants to mobilize society behind an ethnic principle needs an enemy. If it does not exist, he needs to invent one. That is what Hitler did when he espoused anti-Semitism. In the post-Communist world, you don’t need to look very far because communism, in its universalist zeal, suppressed national and ethnic interests, and there are many scores to settle.

Instead of a single power seeking world domination, as in the case of Hitler’s Germany, there will now be a multiplicity of local conflicts. But the effect on the world may be equally devastating. You can be sure that the lessons of a Serbian victory in Bosnia will not be lost on Russia and the other former Soviet Republics—not to mention the boost that the suffering of defenseless Muslims is going to give to Islamic fundamentalism in places like Egypt and Algeria—or in Western Europe for that matter. The Armenians are already engaged in ethnic cleansing around Nagorno-Kharabakh; the rulers of Uzbekistan are extending their control over Tadzhikistan, causing more than 100,000 people to flee to Afghanistan; Russia is sponsoring separatist movements in Abkhazia against Georgia and in Trans-Dniestria against Moldova. The Russian parliament has recently proclaimed sovereignty over the Crimea; Yeltsin is firmly opposed to this declaration but Vice-President Rutskoi, who proposed it, now ranks higher in public opinion polls than Yeltsin. Russian policy toward Estonia and Latvia has visibly hardened in recent weeks. The chances of a Russian Milošević arising have greatly increased.

What is most disturbing is the way the democracies are responding to the threat of nationalist dictatorships. Democratic leaders often avoid hard choices. That is what happened before World War II and that is what has happened in Bosnia. We recognized Bosnia but we were not willing to defend it. We abhorred ethnic cleansing but we were not willing to use force to resist it. Instead of taking a firm stand somewhere along the way, we chose policies of conciliation and humanitarian assistance. But we did not insist that fighting stop before the parties entered into peace negotiations. By making it clear that we were not willing to intervene militarily we set into motion an infernal machine which inflicted the greatest possible suffering on the civilian population short of total destruction. When atrocities and hardships were shown on TV screens, public opinion in the West was aroused and governments said they were contemplating some military action; the aggressors backed down. And when the news coverage subsided, political will evaporated and aggression could be resumed.

The authority of the United Nations has been severely undermined in the process. Blue helmets used to afford soldiers some protection but that is no longer the case: the deputy prime minister of Bosnia was murdered in cold blood while under the protection of United Nations troops, and in July a group of British soldiers wearing blue helmets were disarmed by Bosnian mercenaries. The so-called safe areas are miserable refugee camps that are anything but safe. In early August, UN troops in Sarajevo were shelled by Serbian artillery. The UN response was a weak statement warning, “Don’t do it again.”

The British government has played a particularly insidious role. Having a peace-keeping force on the ground, it used the safety of its troops as an argument for dissuading the United States from using air power on the rare occasion when it was ready to do so. The fact is that British troops are nowhere stationed in locations where they could be directly threatened by the Serbs. They are exposed to the Croats and Muslims. Only when they are escorting convoys do they come into contact with the Serbs and they have done very little of that lately. Therefore the British argument has been merely an excuse for inaction.

Not that the United States government was all that eager to follow through on its threats. Certainly the US military leaders have been keen to stay out of Bosnia. The lesson they have drawn from the Gulf War and the Vietnam years is that military action should be confined to situations in which we have a clear objective, can bring overwhelming force to bear, and can accomplish our goal with minimal loss of life; incremental and openended engagements are to be avoided at all costs. Bosnia is ruled out on all these grounds. When Warren Christopher went to Europe for consultations he practically asked to be dissuaded. The image of Warren Christopher wringing his hands and saying “We have done what we could” will have a prominent place, I suspect, in the history of appeasement. Two days after Christopher made his public statement, Sarajevo suffered the worst shelling in its history.

Advertisement

The whole story is so disgraceful and the situation in Bosnia so pitiful that most of us do not even want to think about it. Our ability to suffer humiliation and to sustain moral outrage has its limits. I know this from my own experience. I set up a humanitarian foundation for Bosnia as an expression of my outrage and in the hope of goading leaders of the civilized world to take a firmer position. I have become deeply involved in Bosnian affairs. My foundation provided fuel to Sarajevo during the winter, repaired and extended the gas lines, helped restore the bakery, provided seeds for planting. The only clean water that is available in Sarajevo today has been installed and maintained by my foundation. It consists of two deep wells from which water is pumped to water taps that are out of sight of the snipers, though unfortunately not out of range of the artillery. But lately I have found myself avoiding having to deal with Bosnia. It is just too painful. I notice a similar tendency among policy-makers and in the press and television.

The Western powers seem to have written off Bosnia. But the cup of humiliation is not yet empty. Indeed, the worst may be yet to come. In early September, as I write, the terms of a settlement have been laid down but the Bosnians are unwilling to accept what amounts to a surrender. The settlement calls for a loose confederation of mortal enemies. The country would be divided along ethnic lines with the Serbs and Croats keeping most of their gains and Sarajevo and Mostar coming under UN administration. Some 40,000 to 50,000 troops would be required for peace-keeping.

The agreement sets a bad precedent. The fate of Sarajevo is particularly distressing. Sarajevo has been the most cosmopolitan, tolerant, and civilized place in the whole of the former Yugoslavia. It is a city where people are actively opposed to the principle of ethnic or religious discrimination, where four different religions have coexisted for centuries (there has been a large Jewish community there since the fifteenth century when they were ethnically cleansed in Spain), where YUTEL, a Yugoslav television station, found refuge when it was forced out of Belgrade. It is an irony of fate that the Muslims in Bosnia are city dwellers and far removed from the fanaticism we have come to associate with parts of Islam; Yet they have taken the brunt of ethnic cleansing. Anti-Muslim prejudice has undoubtedly played an important part: it has influenced European policy toward Bosnia at every level; it has permeated even the United Nations forces and the humanitarian effort. But the prejudice has been ours, not theirs.

What is to be done now? It would be inappropriate to oppose the agreement because the only available alternative is to continue a fight that may lead to the complete annihilation of Bosnian Muslims. There is a danger that the infernal machine may be switched on again, and Western public opinion may be willing to tolerate even greater pressure on the civilian population because it is the Bosnians who appear to be obstructing the agreement. The initial reaction of the US administration after the negotiations broke down at the beginning of September was the correct one: it warned the Serbs against renewed aggression. It is to be hoped that the US is willing, if necessary, to back up its words with actions. Indeed, it would be desirable to have some show of force, even at this late stage, in order to demonstrate that there is a point beyond which the United States cannot be pushed. The peace, when it comes, will be difficult to keep. UN troops may yet find themselves enforcing a peace they ought to have fought to prevent. The settlement which is currently envisioned may be considered the next-to-the-worst outcome.

We must learn from the mistakes that were committed in Bosnia, otherwise the pattern is liable to repeat itself. We must recognize that the world order as we have known it since 1945 came to an end with the collapse of the Soviet empire. Instead of two superpowers keeping each other in check, there is only one superpower left and it is unsure of its mission. It is certainly unwilling and unable to fill the vacuum left by the collapse of the Soviet empire. Nor is it willing to throw its full weight behind the United Nations. On the contrary, it seems determined to draw a sharp dividing line between its own forces and those of the United Nations. It jealously guards the reputation of its own forces but does not care about the prestige of the blue helmets. That much is clear from recent experience.

Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali has sought to build up the authority of the United Nations but he ran afoul of the European Community. At the same time, events have shown that the European Community is unable to develop a common foreign policy. Yet we desperately need a new world order, otherwise we are going to have disorder. We must agree on some basic principles, otherwise our civilization is truly in trouble.

I have a suggestion that may raise some eyebrows. I propose that the principle of open society ought to be accepted as the basis of a new world order and the creation and preservation of open societies ought to be recognized as the prime objective of foreign policy. This idea is very far removed from current thinking, despite the lip service we pay to democracy everywhere. Foreign policy is supposed to be concerned with the pursuit of national self-interest and most people do not even realize that they are living in an open society. By an open society I mean a society where no dogma has a monopoly, where the individual is not at the mercy of the state, where minorities and minority opinions are tolerated if not respected. I learned the urgency of this at an early age when I nearly ended up in a gas chamber on account of my ethnic origin.

Once we recognize the principle of an open society as the prime objective of foreign policy many things become much clearer. We can see some of the mistakes we have made. The US and its allies ought to have worked for the internal transformation of both Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union instead of trying to use them as pieces on a geopolitical chessboard; and we ought to have applied the criteria of open society before we recognized any of the successor states. Then we would not have recognized Croatia without first insisting that the Serb minority there should be adequately protected; and we would have been more aggressive in protecting Bosnia—not to mention Macedonia, whose government is desperately trying to preserve a multi-ethnic state. Macedonia is at the mercy of Greece and Yugoslavia today, and its leaders have practically no choice but to break the embargo because they get no support from Europe.

We would also know better what to do in the days ahead. First, we would persevere with the prosecution of war crimes, making use of the tribunal authorized by the Security Council, in order to prevent the spread of the techniques of ethnic cleansing employed in the former Yugoslavia. There is enough evidence to justify indictments, and if we and other nations maintain pressure on Serbia and Croatia we ought to be able to bring some of the criminals to trial. After all, we have not given up on the Lockerbie case and Qadhafi is still an international outlaw. Embargoes are often counterproductive unless they have a well-defined objective. In the case of Yugoslavia we cannot afford to lift the embargo because it would make Milošević the undisputed victor What could be a better objective for maintaining the embargo than the prosecution of war crimes?

Second, we would do more to fill the vacuum left by the collapse of the Soviet empire. We would reestablish a credible international deterrent force to provide some protection against aggression; without such a force, violence is bound to spread. We would redefine the mission of NATO. What is the point of maintaining a powerful military force if we do not know how to use it? NATO provides automatic protection to its members. Such automatic guarantees could not be extended to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe because the risk of getting embroiled in local conflicts would be too great; but there is room for associate membership and conditional guarantees. In deciding on the conditions, the criteria of an open society ought to be applied.

But deterrence is not enough. We should also try to provide constructive alternatives to ethnic strife. I first proposed a new kind of Marshall Plan in 1988—to be financed largely by the European Community—at a conference in Potsdam, which was then still in East Germany, but I was literally laughed down. Now that unemployment is rampant throughout Europe, while the countries of Central and Eastern Europe are in desperate need of investment, it may be time to think about it again. But first things first: we must deal with Bosnia, or what is left of it, while it is still there.

—September 9, 1993

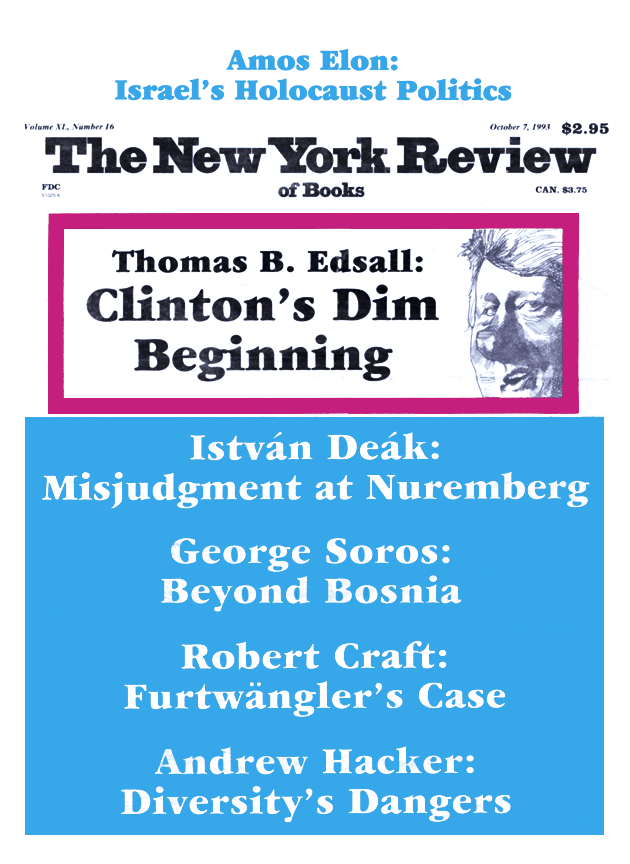

This Issue

October 7, 1993