There’s a distant winking of lights in the gray cityscape of Olafur Olafsson’s Absolution: we’re approaching Christmas. The holidays aren’t an occasion that the book’s aged hero, an Icelandic-expatriate-turned-New-Yorker named Peter Peterson, is likely to make much of. Even so, the lights are there, conspiring in their gaiety and warmth to censure Peterson, who is as chilly a misanthrope as any literary character I’ve met in years. Absolution is a sort of dissonant Christmas Carol, the tale of a Scrooge whose holiday ghosts inspire not redemption but only increased bile and bitterness.

Is it too late? Scrooge wondered when the empty shambles of his life—as cold and glintless as any dead bed of embers—was arrayed before him. By contrast, it’s not a question old Peterson need fret over. He knows the time is past for untangling the bitter knots of his existence. It is too late to substitute another family for the “greedy, despicable, trivial” bunch whose attentions he ignores or deflects: a “stupid and vain” ex-wife and two children he dismisses as “weaklings.” It is too late for the “power and toughness” of sexual exultation, the pursuit of some woman who “will wrap herself around me like the crown of a flower around a sunbeam,” although the young Cambodian woman he lives with (his former secretary) would probably prove compliant. And it is too late—much too late—to undo the mysterious “little crime” that has dogged him for something like half a century.

Peterson conducts his readers backward, first to his schoolboy days in Reykjavik, then to his subsequent pursuit of a business education in Copenhagen, a city to which Icelandic students of Peterson’s generation traditionally turned for advanced study, for at that time Iceland was still a Danish colony. The year is 1939 and within a few months of Peterson’s arrival the country has been overrun by the Nazis. Peterson’s “little crime”—the details of which he is slow to the point of coyness in revealing—is therefore placed against a background of crimes almost too large to compass.

Fortunately, the reader’s surmises outrun the slow pace of the story’s revelations: it becomes clear that Peterson has somehow betrayed a fellow Icelander named Jon, who is active in the fledgling resistance movement. Although Peterson keeps his deliberations to himself, we sense that he is mulling things over, while surreptitiously establishing the contacts among the Nazis which would allow him to be an informer against Jon. Why would Peterson do such a thing? From his point of view, what Jon is “guilty” of is nothing more than sleeping with a young woman, Gudrun, whom Peterson himself has been seeking, unsuccessfully, to sleep with, and Peterson’s act of betrayal seems as much a lashing out at his own shortcomings as a venting of hostility toward a rival; at bottom, Absolution is steeped in self-hatred.

After he informs on Jon, Peterson leaves Copenhagen, and the woman he covets, far behind him. He returns to Iceland, and from there journeys to New York City, where he becomes a purchasing representative for an import-export concern, a field in which he quickly prospers. He turns out to be the perfect middleman, adroit at playing off one side’s desires or inattentions against another’s. But as the decades pass, Gudrun remains for him an obsessive symbol of balked desires, failed opportunities. Although he makes no attempt to look her up after the war, their clipped farewells in Copenhagen—so far as Peterson is concerned—have ended nothing. The book is intermittently addressed to her. It has continual recourse to a “you” (“Did you always intend to humiliate me?” “How could I live on hatred alone, you might ask”) who is finally less a lost love than a judge and jury. Peterson’s obsession takes the form of a wistful conviction that life might have been otherwise—no festering fury, no impulse to commit a “little crime”—had Gudrun only consented to marry him:

How well it could have all turned out if you had not turned against me. Our stay in Denmark and all the years afterward: endless celebration. I would have done anything for you. At the slightest hint of a wish on your part, I would have waded swamps to make it happen. You needed only to whisper it to me while I slept.

Peterson’s crime seems to him “little” in the hair-splitting sense that he has conspired to dispose of his rival while keeping his own hands unbloodied. He has merely been a provider of information to the Nazis, and tries to convince himself that how the Nazis disposed of Jon is none of his business. But his crime is an act that, whatever the extent of his wrongdoing, refuses to go away. He cannot reconcile himself to what he has done. He’s a man with an elastic conscience, who has no difficulty conceiving of himself as someone whose business practices are tawdry and unscrupulous, whose social interchanges are marked by brusqueness and vituperation, whose love life has been duplicitous and self-serving. Rather than shrink from such judgments, he revels in them.

Advertisement

But he cannot quite assimilate the notion that he may be, even by indirect means, a murderer. The world that Peterson inhabits is a merciless environment, whether one is doing business or fending off visiting family, but it’s a place that steadfastly clings to a few norms of decency. Peterson might be perfectly content to be labeled a real-son-of-a-bitch. But in the novel he asks, mournfully, Am I truly an evil person?

It’s a question readers may find easier to respond to than Peterson himself. Yes, you are, they’re apt to answer. And, in addition, you’re ill-tempered, myopic, petty, foul…. The more pressing question for the reader is: Does the world need another book about a hateful man? To which this reader, anyway, answers, Yes—provided the tale shows the craft manifested here. The novel’s plotting is neatly and powerfully accomplished—the reader is pulled along—and the many flashbacks are deftly interwoven into the bleak present day. Although Peterson may seem, in his thorough-going hard-heartedness, his raging at the human “scum” of New York’s “layabouts, thugs and crooks,” an all too predictable figure, life perversely contrives to spring on him a bitter surprise or two, when the aged Gudrun reappears after many decades.

With her arrival, the consequences of Peterson’s betrayal ramify in rich and unseen ways. She wants to tell him about what happened to Jon—news that Peterson has deliberately avoided for half a century. He tries to shut her up, but she is not to be silenced. And in her chatty, unflappable way, she lets fall that Jon is, in fact, well. After the war, he remained in Copenhagen, became a schoolteacher, married a Dane. He sends his regards…. Evidently, Peterson’s informant didn’t believe the information he had been given, or didn’t himself support the Nazi cause, or perhaps issued a report that got waylaid. In any event, Peterson’s evil act somehow “fell through the cracks.”

The book meditates fruitfully upon that fateful schism between intention and result which confounds any criminal justice system yet devised. Readers will find themselves meditating on just the sorts of questions that bedevil first-year law students: If two hunters out in the countryside discharge their rifles randomly into the air and the first hunter’s bullet lands safely, while the other’s strikes and kills a farmer, what exactly is the second man guilty of that the first was not? And conversely: If two men shoot to kill an innocent bystander, but the first man’s gun has been, unbeknownst to him, loaded with blanks, how is he less culpable than his counterpart? It’s on questions just as elemental as these that the novel ultimately hinges. What precisely is Peterson guilty of? Is he more or less blameworthy for not knowing why his intended crime went unfulfilled? If such quandaries are finally unresolvable, their contemplation is surely a positive good; there is doubtless something salutary in being asked to answer the unanswerable. Absolution sets long reverberations tolling in the reader’s mind.

While I have no problems, aesthetically, with a narrator of Peterson’s cruelty, in this case I did find myself somewhat troubled by his transparency. Experience teaches most of us, I suppose, that the sort of evil Peterson embodies—a daily and unspectacular sort, that of the man who will wordlessly injure and betray friends and acquaintances when they get in his way—customarily cloaks itself in pieties and opacities, in bluster and double-talk; its defenses are more cunningly elaborate and devious than what Peterson erects. Peterson is always reminding himself that nobody should be trusted, but Olafsson does not seem fully to trust in the psychological penetration and subtlety of his readers. The book seems far stronger as a piece of construction—of plotting—than of portraiture. In the depiction of malevolence he gestures too broadly, lays the irony on one layer too thick. The story too often denies the reader the devilish fun of rooting out its special nastiness.

Readers familiar with Iceland may be chagrined to discover that Reykjavik—that bleak and enchanting capital city—is rather fuzzily evoked in the pages of Absolution. In a curious twist, the book’s scenery and backdrops sharpen the farther they range from the author’s homeland. The novel’s Danish flashbacks have a greater vividness and tactility than those set in Reykjavik, and the New York sections are solider still.

Advertisement

If I didn’t know a little bit about the author (who, while yet in his early thirties, represents to his countrymen not only one of the great hopes of contemporary Icelandic letters but a transplanted success in international business: Olafsson is president of the Sony Electronic Publishing Company in New York), I might well have believed he’d come from elsewhere. Iceland, with its population of roughly a quarter million (smaller than that of Birmingham, Alabama), exports few novels into English. But in Halldor Laxness, who received the Nobel Prize in 1954, this little country has produced a magnificent and prolific writer.

Absolution seems far removed from Laxness—whose books, even at their most heart-breaking, have the spaciousness that comes from a defiant sense of humor—and, so far as I could see, from Icelandic fiction generally, with its roots, traceable back to the medieval sagas, in the earth. In Icelandic sagas, seemingly every stream, valley, even boulder through which their stories pass is identified by name. And in Laxness, as is also true in Hardy, the characters are often dwarfed by the immense sweep of the landscape that surrounds them. Absolution’s atmosphere often has an indeterminate feel—though northern European, perhaps, in its quiet brooding and glowering iron-gray skies.

Whatever its creative and spiritual sources, Absolution represents an honorable addition to a robust international tradition which might be called Tales of a Soured American Pilgrimage—chronicles of men and women who flee to the US hoping to find a fresh start but who discover that the sins or ghosts of the Old World infect the New. Peterson’s “little crime” pursues him across the sea; not even the airy sanctuary of his Upper East Side apartment is proof against it. He has sought to close himself up like a fist. At the novel’s finish, when his health is faltering and he comes undone—when, that is, the fingers of the fist open—we see that, all along, the hand was empty: Peterson reveals a mendicant’s open palm. His entire life, he concludes, has been built on “deception.” And now, at last, it seems that Peterson, who has always prided himself on asking charity of no one, wants our sympathy. It’s a testimony to the artfulness of Olafsson’s story that we’re willing to grant it to him.

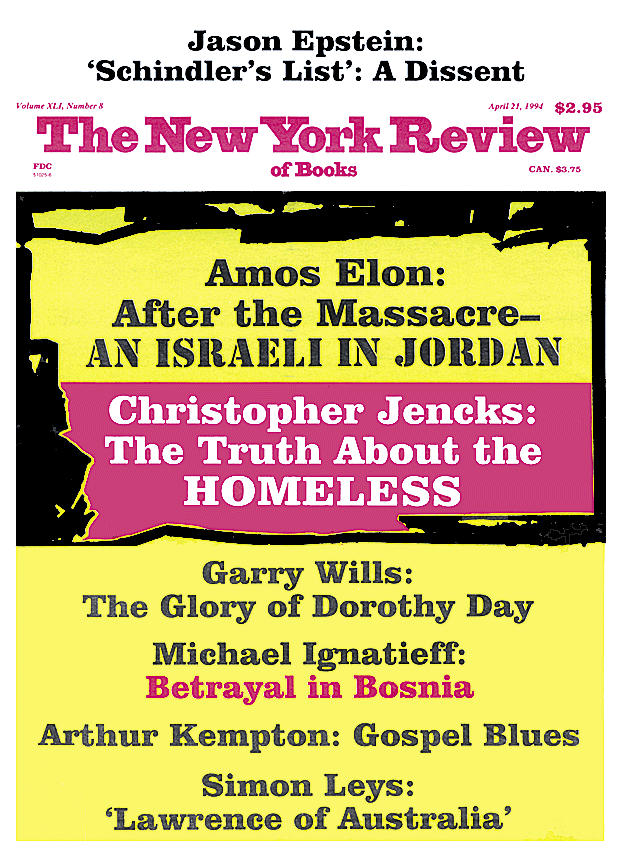

This Issue

April 21, 1994