Ever quick with a pun (“Veni, vidi, Vichy,” he wrote triumphantly of taking the waters), Berlioz gave his last collection of essays a trick title that serves to remind us how thoroughly Art and Nature (chants/champs) mingled in his thoughts. But for the most part A Travers Chants abandons wordplay and the satire of which its author was so fond to concentrate on the repertory that had taught him how to compose to begin with, and that went on to sustain his muse for a lifetime: the great works of Gluck, Beethoven, and Weber.

Music journalism in the nineteenth century—by several measures the golden age of newspapers and weekly reviews—offered composers an opportunity to earn money and make their views known, and those gifted with a degree of literary skill found their services much in demand. Spohr and Weber were both good writers; in Leipzig Robert Schumann established the powerful Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, filling its pages with the lively musings of his various alter egos and welcoming in due course Chopin and Berlioz and Brahms to his imaginary Davidsbund of progressive artists posed against the philistines of music. Liszt and his female admirers composed hundreds of pages of prose, including a five-installment study of Berlioz’s second symphony, Harold en Italie. Wagner bored his friends and posterity alike with his published polemics, most of them to one degree or another naughty. Patrons of the newsstand constituted enough of a market to sustain several dozen music critics in Paris alone.

To Berlioz the papers offered a welcome source of income, money that often made the difference between a pitiful level of subsistence and something approaching bourgeois comfort. His salaried position as librarian of the Conservatoire was mostly honorific, providing only a small monthly annuity. It was a matter of luck if his concerts broke even; receipts from his hundred or so performances abroad barely met the expense of transporting himself and his trunks of music across Europe. His scores earned him little enough, from a few dozen to a few hundred francs for one-time sale to the publisher. (Shortly after the appearance of A Travers Chants, Berlioz’s operatic masterpiece Les Troyens sold for 12,500 francs—a princely sum, the equivalent of a year’s salary; but a full score and the corresponding orchestral parts were never published, leaving successive generations without a decent musical text, the very outcome he feared most of all.)

His weekly reviews paid for the groceries. And for all his petulance over how his newspaper work stole from him the time to create work of more lasting value, his tripartite career as composer, conductor, and journalist proved an altogether practical solution to the question of how a citizen composer of the new era might sustain daily life.

Berlioz, whose mind Rouget de Lisle thought “a volcano in perpetual eruption,” was seldom short of words, and as early as 1823, at the age of twenty, he was volunteering his way into the profession with acerbic letters to the editor of a small Paris paper called Le Corsaire. These established his lifelong critical demands that performers should be absolutely faithful to the composer’s score and that composers should have the purest motivations in practicing their craft. From the start he was quick to ridicule musicians and the public whenever he suspected a trivializing of the quest for beauty or any of the other behaviors he would later come to call “les grotesques de la musique.”

“Why do singers shriek at the Opéra?” he asks in his first published letter. (Then he provides a remarkably astute answer: “Because the tuning pitch there is a tone higher than it ought to be.” Like virtually every other insight of those formative years, this one became a cause to be pursued, and in 1859 it was Berlioz who did the research and published the manifestoes that led to the establishment of a universal pitch standard, A=435.) The work of dilettantes—Schumann’s philistines—drew the full measure of his wrath: the roulades Mme. Sontag added to a Mozart aria, for example, or Castil-Blaze’s rewriting of Der Freischütz as Robin des Bois. The bêetises he overheard in the foyer of the Opéra or in the rue Bergère outside the Conservatoire—“Ah! Gluck: he never wrote music, only plainchant”—typically found their way into his next essay.

Already in the earliest pieces Berlioz elevates Gluck, Spontini, Weber, and Mozart to his musical Olympus. “All the Rossini operas taken together,” he writes in Le Corsaire, “fail to compare with a single line of Gluck recitative, with three measures of a Mozart aria.” Gluck’s lyric tragedies, such as Iphigénie en Tauride (1779), were his models for clarity of dramatic expression and sobriety of means, for stylishly contoured melody and for orchestrational device of the proper hue; ultimately they inspired the last of the true tragedies-lyriques, his own opera Les Troyens. In the late 1820s he begins to exalt Beethoven, following the Paris premieres of the symphonies and Berlioz’s own page-by-page score study in the Conservatory library.

Advertisement

Discovering Beethoven in 1828–1829 showed him his compositional path to the Fantastique, largely by suggesting ways (unknown so far in the French repertoire) that the materials of symphonic discourse could be harnessed to narrative or descriptive effect, as is the case in all the Berlioz symphonies. His 1838 cycle of articles on Beethoven’s symphonic oeuvre is arguably the first great critical treatment of that corpus in any language—and in A Travers Chants it is reprinted in full. To read it at a stretch is to be reminded again how thoroughly Berlioz’s conceptual world was shaped by Beethoven; it is often as though each new sentence speaks at once of the Beethovenian subject matter at hand and its eventual reflection in his own music.

Before the concerts of the Conservatory Orchestra, amateurs and savants alike had faltered over Beethoven, and this time Berlioz had a hand in winning them over. The Ninth Symphony was found by one critic, Berlioz tells us, to be “not altogether devoid of ideas, but they are so badly organized that the general effect is incoherent and lacking in charm.” And if Berlioz himself was sometimes perplexed by what he heard, the puzzlement would merely send him back to the scores to seek his own explanations: there was little precedent analysis for him to read, and in Paris no journalist any better informed than he.

Though the terminology at his disposal was barely sufficient to account for the advanced music of Beethoven, Berlioz set about explaining his innovations through a combination of technical analysis and emotive response. Attempting to explain the wonder of the famous transition from scherzo to finale in the Fifth, he writes:

The strings gently bow the chord of A-flat and seem to fall into slumber while holding it. The timpani alone keep the rhythm alive by light strokes from spongecovered sticks, a faint pulse beating against the immobility of the rest of the orchestra. The notes the timpani play are all Cs, and the key of the movement is C minor; but the A-flat chord, held for a long time by the other instruments, seems to introduce another key, while at the same time the lone throbbing of the timpani on C tends to maintain the feeling of the original key. The ear hesitates, it cannot tell where this harmonic mystery is going to end.

True enough, and probably accessible to a certain number of his readers. But it was the overt Romanticism of Beethoven that summoned his best writing: “the shreds of the lugubrious melody, alone, naked, broken, crushed” at the end of the Eroica funeral march, the wind instruments “shouting a cry, a last farewell of the warriors to their companion at arms”; the “magnificent horror” of the storm in the Sixth; the “rainbow of melody” and “profound sigh” in the celebrated Allegretto of the Seventh. Berlioz describes the Allegretto scherzando of the Eighth Symphony as “gentle, innocent, and gracefully indolent, like a tune two children sing while gathering flowers in a meadow on a fine spring morning,” and it is no coincidence that he models on this very idea the Villanelle from Les Nuits d’été, where the image is of young lovers gathering wild strawberries in spring. The Romantic and post-Romantic orchestral repertoire is of course rife with such references to the Beethoven symphonies, but in Berlioz’s case the affinities are exquisitely close: between the Eroica march and the gripping Marche funèbre pour la dernière scène d’Hamlet, or with the thematic reminiscences in the finale of Harold en Italie so obviously modeled on the Ninth, or the choral finale of Roméo at Juliette—just to begin a long catalog.

Well read in poetry and well schooled in clinical diagnosis, he was quick to spot the particular details that would forever fix his point in the reader’s memory. Both Cherubini and the conductor Habeneck are remembered today largely from Berlioz’s vignettes: the one as arch-bureaucrat and imperfect francophone, wobbling on his cane as he crossed the Conservatoire courtyard, the other for a pinch of snuff said to have compromised the first performance of Berlioz’s Grande messe des morts in 1837. Not a word written in 1837, by Berlioz or anybody else, suggests Habeneck was incompetent as a conductor or on a snuff high. The Berlioz account doubtless amounts to a conflation of incidents that took place over the course of a decade or more. But it’s a good story, and the snuffbox went on to become Habeneck’s attribute just as surely as the ear trumpet is Beethoven’s.

Advertisement

For raconteurs like Berlioz, the bon mot is often, after all, the point of journalism. Posterity has for all intents and purposes forgotten Carafa’s La Grande Duchesse (1835), but devotees of opera lore still merrily quote Berlioz’s review: “Madame se meurt! Madame est morte!!”

His satire was relentless, and however noble its intent it inevitably turned the establishment against Berlioz’s music. He in turn increasingly took his music elsewhere, abandoning Paris to its pettiness:

We continue in Paris to make such [trivial] music—we have become so prodigiously Spice Merchant, so National Guard, so Deputy, so ill-bred, so stingy, so greedy—that during my absence I will rest easy on the question of being homesick. From that I shall not die.

But he would always come home. Paris was, he discovered, “an electric city which attracts and repels in alternation, but to which one must definitively return when in its grasp, and especially when one is French.”

Berlioz’s feuilletons appeared in the Revue et Gazette musicale, a weekly periodical offered by Maurice Schlesinger’s music publishing house and devoted largely to historical essays and concert reviews, seasoned with a good deal of gossip about the musical personalities of the day; and in the Journal des Débats, the influential daily newspaper owned and run by the Bertin family. At the R&GM, Berlioz quickly became a senior figure, called to serve as acting editor when Schlesinger went to attend to his Berlin office. At the Débats Berlioz’s stature (and that accorded to arts criticism in general) is indicated by the placement of his biweekly column at the foot of the front page. Berlioz and his gifted contemporary Jules Janin made the Débats the organ of some of the era’s most powerful and persuasive criticism.

His assignment was to cover the central institutions of French music-making: the Opéra, Opéra-Comique, and the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (the Paris Conservatory Orchestra, which emerged in Berlioz’s lifetime as the best in the world). Much of his work thus consisted of reviews of performances, documenting the often tortuous progress of the French lyric stage and the annual symphony series which within a couple of decades had become so predictable in their flawlessness and so narrow in their repertoire that too often there simply wasn’t much to say.

Relief from the tedium of Parisian musical life came with the period of Berlioz’s vagabondage. His wonderful letters home on discovering the world beyond the Rhine—on his neglect at the hands of the self-satisfied Frankfurters, his dazzling success with the tiny court orchestra of the Prince Hohenzollern-Hechingen, and the warm welcome of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (“Venez! venez!” urged Mendelssohn)—filled his Débats columns of 1843 and were devoured in the German translations published in Schumann’s Neue Zeitschrift and a Hamburg Kleine Musik-Zeitung: the Germans, it was rightly imagined, were anxious to read what Berlioz had written about them.

From Bonn in 1845 he described the unveiling of the Beethoven monument; from Lille the next year he recounted the grand opening of the Paris-Brussels railway, for which he and Janin provided the ceremonial cantata. (On short notice. But “the nation,” he thought, “has the right to ask of each of its children an absolute commitment. And so I said to myself: ‘Allons, enfant de la patrie!’ “) From Russia in 1847 and the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1851 he wrote of the choral performances that went on to inspire the Te Deum of 1848–1849 and its 1852 revision. His enthusiastic reports from Lyon eventually prompted the elevation of the local conductor George Hainl to the podium of the Conservatoire orchestra, a post Berlioz had wanted for himself.

Always there are intriguing hints of work in progress: from the spa in Plombières-les-Bains, he describes composing a portion of Les Troyens at the Stanislas Fountain; from Baden-Baden, where he conducted a summer festival, he recounts some of the circumstances surrounding the composition of Béatrice et Bénédict. Both the detail and the candor of Berlioz’s epistolary style have been central in our effort to piece together his creative process: in this case describing how the text of the Duo-nocturne from Béatrice was begun while wandering among the ruins of the old castle at Baden-Baden, the result proudly presented to his reader as something “I shall soon set to music.” (In a different letter we learn that the music was later composed during a wearying speech at the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut de France.) Then there would come the drafting, polishing, and diligent post-performance rewrites that brought his works to their perfection—a process quite often to be traced through asides in his columns.

Berlioz liked to call these pieces his “Diplomatic Correspondence,” while the wags and cartoonists dubbed them “Dispatches from the Grand Army.” The public seems not to have tired of reading what he had to say—certainly his publishers went on printing it—despite the formidable quantity of it all. In total there appear to be just short of a thousand signed pieces,1 not counting the unsigned press releases he wrote about his own music or the hundreds of gossipy paragraphs in the R&GM that must have come from his pen.

Then, as now, it was customary for the best critics to gather their favorite columns for a book. Berlioz obviously enjoyed the meticulous pasting up of his old feuilletons, correcting, revising, and knitting them together as he went. The first book assembled along these lines was his text on the orchestra, the Grand traité d’instrumentation, drawn from the sixteen articles he wrote for the Revue et Gazette musicale in 1841 and 1842 and published in 1843—chronologically and geographically at dead center of the revolution in instrument manufacture which produced the great post-Romantic philharmonic societies and their repertoire.

For one of his next books Berlioz had the amusing idea of presenting his essays as the bavarderies of bored pit musicians, conversing about serious music while playing (or not) the trivial repertoire. This was Les Soirées de l’orchestre (“Evenings with the Orchestra,” 1852), beloved ever since—along with its sequel, Les Grotesques de la musique (1859)—for the seemingly effortless mix of solid content and wry humor Berlioz was able to muster whenever he was in peak form. Meanwhile, still using the cut-and-paste method, he was assembling his Mémoires, to which he would return from time to time as circumstances seemed to dictate, generally during periods of bleakness, discontent, and failure.

Except for adding a final postscript to the Mémoires, dated January 1, 1865, Berlioz’s last major literary effort was to assemble A Travers Chants. Some 1,500 copies were published in September 1862, to generally favorable critical response and what appears to have been a brisk sale. In Germany Richard Pohl, who was already translating Béatrice et Bénédict, began the German version as soon as he received his copy.

In A Travers Chants we encounter a variety of subject matter that extends from plainchant to the music of the Asian cultures Berlioz encountered at the world’s fairs. He was nothing if not curious: an intellectual gadfly, his facts and ideas absorbed from encyclopedic reading and a lifetime of mingling with intellectual aristocrats. His store of information is sometimes imperfectly remembered, or based on erroneous hearsay: it was the chronological order of Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth that was at issue, not the Seventh. But where the disfigurement of a masterpiece was suspected, his memory of the authentic original was virtually flawless. Thus his vexation with the 1859 Paris production of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail (a work he did not even like) on the grounds that the publicity promised “the most scrupulous fidelity,” whereas in fact the opera had been compressed into two acts, its numbers rearranged with “Martern aller Artern” assigned to Blonde, and the Rondo alla turca for piano inserted as an entr’acte.

Concerning Gluck, Berlioz’s scholarship and understanding had become legendary. A Travers Chants coincides with Pauline Viardot’s celebrated appearances in Orphée (Théâtre-Lyrique, 1859) and Alceste (Opéra, 1861), both productions owing a great deal to Berlioz’s advice. The Gluck essays in A Travers Chants are by far the longest in the collection, brimming with memories of the Gluck tradition in Paris and knowledge of the available sources that scholars continue to mine.2 His review of Mme. Viardot’s performance in Orphée occasioned a moment of bad blood between them, when he wondered in print why she made a “deplorable” change by holding a high G at the end of “J’ai perdu mon Eurydice” (i.e., “Che faro senza Euridice”). She responded, testily, that she had sung every note exactly as he had instructed her. But this spat has the markings of a publicity stunt: otherwise Berlioz’s admiration for the woman and her art was unmitigated, as was hers for Les Troyens. They spent long hours together at the piano reading through the score.

Of all the articles in A Travers Chants, the one that remains of the most interest to modern readers is “Concerts de Richard Wagner: La Musique de l’avenir,” first published in the Débats of February 9, 1860. The new champion of Futurism, which had originally claimed Liszt, Meyerbeer, and Berlioz as its gods, was in town to set the stage for the imperially ordered production of Tannhäuser. Berlioz was already crabby over this course of events, Les Troyens having manifestly failed to attract the emperor’s attention; he also felt betrayed by Liszt’s tireless promotion of Wagner, even though Liszt and his lover the Princess Sayn-Wittgenstein had fostered Les Troyens from the start.

But the souring point was Wagner’s new music, notably the Tristan prelude. As usual Berlioz had carefully studied the scores (and remarked to Mme. Viardot, when returning a borrowed copy, that he had feared one of the diminished-sevenths would escape and nibble at his furniture), and these he found beyond his comprehension. He could not help but think what he read and heard to be unmelodic, dissonant, unsingable. He feared that the Music of the Future was that of Macbeth’s witches: “Fair is foul, and foul is fair.” And thus he dismissed Zukunftsmusik with the brusque pronouncement:

If this is the religion, and a new one at that, then I am far from confessing it. I never have, am not about to, and never will. I raise my hand and swear: Non credo!3

With that, some two decades of wary collegiality between Wagner and Berlioz came to an end, as, effectively, did Berlioz’s more intimate friendship with Liszt. The essay was one of Berlioz’s last major critical pieces, and it poignantly defines the aesthetic playing field of 1860, with Tristan und Isolde and Les Troyens as the opposing teams. For Wagner was just reaching his peak, and Berlioz’s active life was nearly done. A Travers Chants includes work published through March 30, 1862, after which there were just over a dozen more columns, concluding with a piece welcoming Bizet’s Pearl Fishers.

2.

Elizabeth Csicsery-Rónay’s edition of A Travers Chants is on the face of it tidy and serviceable, a no-nonsense translation with its several hundred notes stuck discreetly and economically at the back. Jacques Barzun, patriarch of American Berlioz studies, provides a short and unobtrusive introduction. But not sterile: he comes uncomfortably close to reopening the old program-music debate by remarking that “Berlioz believed … the thing called program music was a contradiction in terms.” Today the notion that Berlioz’s work needs hearing as “absolute” music seems a relic of the critical snobbery of mid-century that, we now suspect, drove too much of the public away with its continued scorn for the simple pleasures of concertgoing. Call the Symphonie fantastique what you will, but civilized people keep on hearing the guillotine chop and head-falling-into-basket in the March to the Scaffold; at the Witches Sabbath they hear the grotesque masculine laughter and shrill feminine giggles that Berlioz himself tells us he put there. Nowadays they hear Romeo bidding “Bonne nuit” to Juliet as well.4

In the half-century since Barzun’s biography5 meanwhile, two generations of Berlioz specialists have filled at least two library shelves with the sort of solid and reliable texts for which Barzun himself called loudly and often: a New Berlioz Edition; a Correspondance générale; two handsome modern editions of the Mémoires; a thematic catalog; three big biographies; and the promise of the complete feuilletons. Most of Csicsery-Rónay’s work, in fact, consists of translating Léon Guichard’s 1971 Berlioz centenary edition of A Travers Chants, down to the turns of phrase of the notes.

But with what result? Certainly not one that evokes the “new” Berlioz, placing the essays in the chronological and biographical contexts we understand today. An attempt along these lines might—to pursue but one example—have led her to avoid the silly remark about the Freischütz that “Berlioz’s music for the recitatives is considered an amazingly Weber-like piece of work.” It is nothing of the sort, but instead the simple hack work of the kind all opera conductors do day in and day out just to get theater pieces on stage. What is interesting, and what might have been noted, is how central Berlioz’s success with the production was to both his income and his stature at the Opéra. How the widow Weber wrote to inquire of the proceeds, gravely embarrassing Berlioz. How (according to Berlioz, at least) the systematic dismemberment of Weber’s original began not “while Berlioz was traveling in Germany in 1842–43,” but in 1847, during the Russian journey. How the editor of the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung named Berlioz in an 1853 suit against the Paris Opéra alleging malpractice with Der Freischütz, and how Berlioz defended himself in the Journal des Débats of December 22, 1853, later writing a Leipzig law student that

I am as blameless in all of this as you yourself. Be further informed that I have shown more proof of my religious respect for the great German masters than you could do in your whole life, and that I am therefore above this sort of perfidious accusation and superficial judgment.

A book called The Art of Music must also face up to the issues of musical terminology and discourse. The petite flûte quinte in Mozart’s Entführung is of course not an alto flute at all, but a piccolo flute pitched on G at the fifth above—like the old treble flute—and nowadays played on an ordinary piccolo. And Berlioz’s old-fashioned manner of identifying chords, translated word for word, leads to countless barely intelligible formulations.6 Why not, for that matter, take the truly modern step of providing the relevant musical examples?

One could imagine someone, in the long chain of professionals who presumably shepherd a scholarly work to publication, wondering about the statement that “in 1861 [in Baden-Baden, Berlioz] assisted the rediscovery of Pergolesi by reviving La serva padrona“—a preposterous idea on the face of it, given Berlioz’s tastes, and manifestly improbable owing to the fact that in Baden-Baden in 1861 Berlioz was preparing a major festival concert—his last there—as well as working up to Béatrice et Bénédict for the opening of the new theatre the next year. In fact the note is miscopied from The New Grove, which reads, “in 1863 [he] initiated the rediscovery of Pergolesi’s works with his revival of La serva padrona.7

But Grove is wrong, too. La Servante maîtresse, in F.A. Gevaert’s new French version, was an 1862 production of the Paris Opéra-Comique, where it opened on August 13—and was put in that time slot because the Comique’s tenor, Montaubry, was in Baden-Baden opening Béatrice et Bénédict, thus interrupting the Opéra-Comique’s highly successful production of Félicien David’s opera Lallah-Roukh. Under the circumstances, it had seemed a good idea to ship the whole production to the new theatre in Baden-Baden for a one-night trial during the opening festivities.8 The eyes of the critics in Baden were primarily on Berlioz’s premiere, but the debut (as the servante maîtresse) of Mme. Galli-Marié, who was to become the first Carmen, was noted with satisfaction.

There is no more fitting proof of the merits of “useful musicology,” as it is being called by the post-Gingrich Davidsbund, than the case of Berlioz. Thanks to the work of scholars and knowledgeable performers, Les Troyens, virtually unknown as late as 1965, has taken its proper place alongside Tristan and Traviata as a cornerstone of mid-nineteenth-century composition, with its published score, productions, and audio and video recordings. American musicology—starting with Barzun—has had a major part in popularizing Berlioz, too. The Fantastique has outdistanced every other symphony of the 1830s and 1840s in programming and record sales; even the production-heavy works—the Requiem, Roméo et Juliette, and Ladamnation de Faust—have become commonplace in live concerts. The factual results of Berlioz scholarship have for the most part trickled comfortably into the lore, replacing the myths of chemical dependency and necrophilia that entertained readers earlier in the century. Berlioz has become an honorable composer, no longer an object of armchair bemusement. To have A Travers Chants properly Englished would have been a step forward, too.

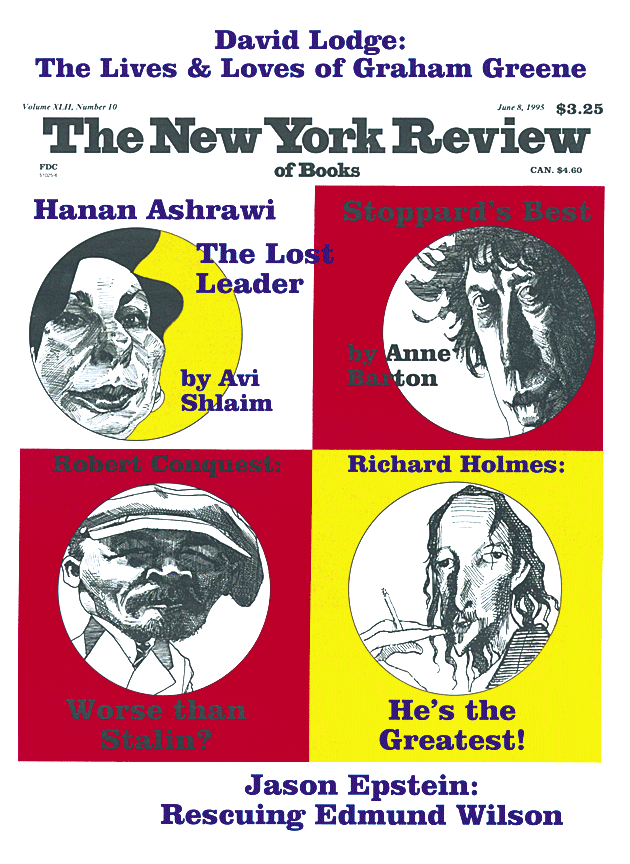

This Issue

June 8, 1995

-

1

I list them in my Catalogue of the Works of Hector Berlioz, New Berlioz Edition, Vol. 25 (Kassel: Barenreiter, 1987): “Feuilletons,” pp. 435–88. ↩

-

2

See, for example, Joël-Marie Fauquet, “Berlioz’s Version of Gluck’s Orphée,” in Berlioz Studies, Peter Bloom, editor (Cambridge University Press, 1992), pp. 189–253. New productions and a recording of the “Berlioz version” are under discussion. ↩

-

3

Translation mine. ↩

-

4

See, for example, Ian Kemp, “Romeo and Juliet and Romeo et Juliette,” in Berlioz Studies, pp. 37–79. ↩

-

5

Barzun’s two-volume Berlioz and the Romantic Century was published in 1950 by Little, Brown; the second edition was abridged in one volume as Berlioz and His Century (Meridien, 1956; University of Chicago Press, 1982); the third edition is for the most part a photographic reprinting of the first, published in conjunction with the Berlioz centenary (Columbia University Press, 1969). ↩

-

6

As he closes the exposition in the first movement of the Seventh Symphony, Beethoven passes through an eyebrow-raising F-major triad on his way to cadence in E major, a progression we would write as ii-N$$$ (or $$$ II6, i.e., a Neapolitan)-V-I in the dominant (V, or E major) of the movement in A major. When the translation talks of “the resolution of the dissonance in the six-five chord above the subdominant note [A] in the key of F-natural,” even the hardy reader will experience a twinge of alarm. And when we read of the F-major triad that “the chord of the fifth and major sixth has thus become a minor sixth without the fifth,” we simply shrug and skip ahead. ↩

-

7

Friedrich Baser, article “Baden-Baden” in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Stanley Sadie, editor (Macmillan, 1980), Vol. 2, p. 7. ↩

-

8

Alfred Lowenberg, in Annals of Opera, (third edition, Totowa, New Jersey, 1978), column 177, lists the Baden performance of La Servante maîtresse as 11 August 1862; if that is the case, it was on the same day as the second performance of Béatrice et Bénédict. Berlioz reviewed the Paris production in the Débats of September 27. ↩