In response to:

Sex, Lies, and Social Science from the April 20, 1995 issue

To the Editors:

Richard Lewontin’s comments on Edward Lauman, et al., The Social Organization of Sexuality [NYR, May 11, 1995] propose to shut off the study of sex in real life because it can only be studied through words, and people lie. His prime example is that men and women report different total numbers of heterosexual sex acts, sex partners, and the like. What is striking about this fact is that it pervades all social groups, all ideologies of what sex is for and who are legitimate partners, cohorts raised before and after the sexual revolution, and those in married and unmarried statuses.

The hypothesis that all these conditions produce sex differences of the same kind in the tendency to lie to sympathetic interviews is a deep and radical, and very unlikely, hypothesis. They lie in the same way regardless of what they think is right and defensible, of very different numbers of new partners, of different frequencies of sex, or of different marital status. What is reasonably clear then is that even the perception of a sex act is socially shaped, and genders define sex differently, so the basic argument of Lauman et al. extends even to Lewontin’s criticisms.

There are three main ways in the United States of defining intimate social activity between men and women as sex acts: male orgasms, penetration, and states of high sexual excitement. Women are from the beginning taught to think of male orgasms as risks of pregnancy, and that makes many things defined as orgasms by males irrelevant and insignificant. Men are taught that orgasms are goals, feelings, and ejaculations. It would be very unusual to come to the same number of sex acts using such different frameworks for what is a significant and memorable male orgasm.

Similarly men are taught generally to collapse penetration, sexual excitement, and orgasm together, because penetration is very difficult without excitement, and most penetrations result in male orgasms (this turns out not to be so obvious, for a small number of sex acts do not produce male orgasms, according to the data). Women are taught that one can have sex without excitement, and many penetrations (as the data show) do not produce female orgasms, and many of the male ones are not especially significant to women. When the degree of overlap of the main criteria for a sex act, as socially defined, is very different for the two sexes, it would be very unusual for them to count the same way. Given these gender-specific cultural definitions, many more patterns of activity are likely to be seen as “essentially penetration” by men than women, and many more states of sexual excitement leading to male orgasm are likely to be seen as “having sex” by men than by women.

In short, a science confronted by an anomaly is not supposed to give up, but to develop a theory of it. The common sense theory that people lie to strangers about intimate things does not predict the ubiquity of the anomaly of the sex difference across situations that ought to produce variations under that theory, that is a particularly bad ground for just forgetting all about it. Ubiquity suggests that the phenomenon is fundamental, and thus ubiquity calls for a theory.

The theory that people lie to make a good impression on interviewers has not proved very fruitful in social science. The difficulty seems to be that nearly everyone thinks it is quite justified to be what they are. They are willing to explain to strangers that justification, if the strangers look as if they are listening. Imagine a Southern Baptist woman believing premarital sex to be a sin making up sins so that her premarital sexual history will be reputably large (in fact Baptists have as much premarital sex as other people, according to Lauman, et al.). Her Southern Baptist husband does the same, because he doesn’t think his religion is as important as impressing a reputable middle class interviewer from National Opinion Research Center. But the woman reduces her imaginary sins, or the man exaggerates his imaginary sins, or both, so that they look reputably far apart. Invent another theory; this one doesn’t fly.

Lewontin needs to look into his own science’s history to see how anomaly is better theorized about than ignored; that’s where the advance of science comes from.

Arthur L. Stinchcombe

Department of Sociology

Northwestern University

Evanston, Illinois

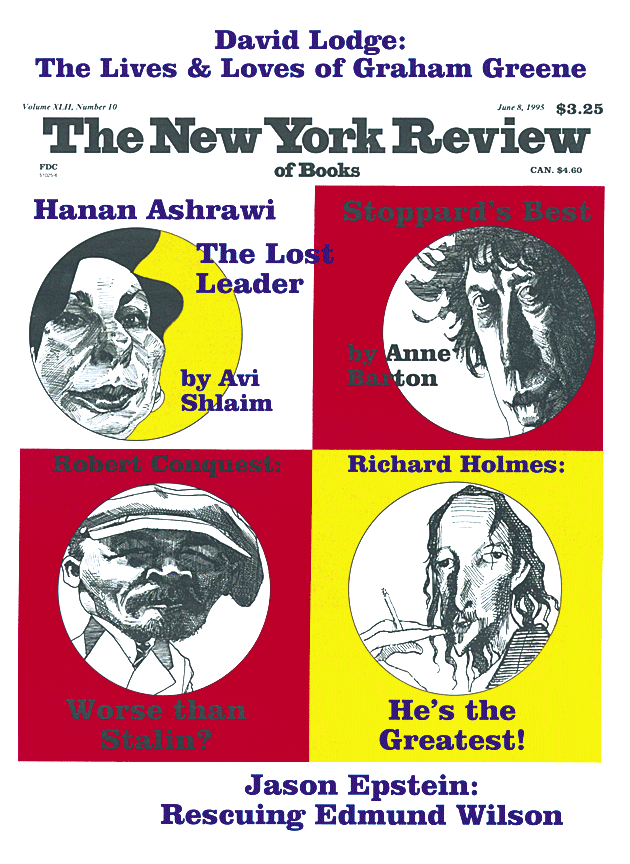

This Issue

June 8, 1995