Some studies of society resemble a garden laid out by Le Nôtre. You saunter down broad avenues, you know where you are going and where you will emerge. Michael Mason’s excellent book on Victorian sexuality is the very reverse. Reading it is like entering a dense forest, where whatever path you take, you have to fight your way through thickets and scramble over fallen trees. The tangle, however, serves a purpose, for Mason’s scruples get in your way and stop you from coming to hasty and false conclusions. No sooner does he generalize than he produces a qualification. Still, his prose is always readable, free from jargon, and it is clinically detached: he is not a journalist nudging, winking, and using four-letter words.

Mason is also an omnivorous reader of memoirs, magazines, demographic statistics, and of secondary sources. Yet there is a strange omission. Although he is a senior lecturer in English literature in London University, Mason does not use novels or even biographies of the novelists to reinforce a point. Does he believe they are less reliable than some of the memoirs from which he quotes?

For the past hundred years the Victorians have been mocked for their prudery and hypocrisy about sex: Who has not heard of piano legs being covered in chintz and human legs referred to as “pedal appendages”? Recently it has become fashionable to scout this stereotype. Did they not behave in bed as we do? Michel Foucault argued that the nineteenth century was one continuous attempt to know more about sex, ending with Havelock Ellis and Freud. You hardly have to read between the lines of Trollope’s novels to realize that his heroines long for the moment when the man they love will embrace them. But Mason is not fooled. Neither Trollope nor Dickens mentioned intimate matters familiar in the novels of Fielding and Smollett. However constant the pleasures of bed, attitudes toward sex had been transformed. Pecksniff and Podsnap ruled.

When did the change take place? That renowned Victorian G.W.E. Russell (whose Collections and Recollections, published in 1898, deserves to be reprinted) put the date as 1790; but toward the end of his life he deferentially moved the date to 1837, when Victoria was crowned. Mason prefers the earlier date and believes the Utilitarian radical Francis Place to be a better guide. Place argued in his autobiography that Victorianism, if understood as a change in attitude, and hence of behavior, began in 1800, at any rate among artisans and the better-off poor. Place thought things changed because men were becoming more rational, more politically minded, were better read and better clothed, educated their children instead of going every night to the pub, and were susceptible to reforming agencies. Tradesmen’s daughters no longer became prostitutes.

Mason’s most interesting chapters are on the sexual behavior of different classes. As usual the evidence is conflicting. The aristocracy were lenient toward adultery—an attitude very different from that of the rural gentry. Certainly if one was the hostess of a country house when the Prince of Wales and his set were staying during the late nineteenth century one needed to know how to arrange, as well as the place à table, the bedrooms in order to avoid embarrassing encounters during the night. But aristocrats were not habitually unfaithful to their wives. Libertines were on the way out: club life—cards, politics, and gossip—supplanted orgies and sexual liaisons. Servants, Michael Mason writes, set an example to their masters. A notorious womanizer excused his hypocrisy in dismissing an erring footman by pleading that the servants’ hall would not allow him to overlook the matter. Another who wanted to pardon an offender also found that the other servants would not stand for it.

Yet foreign observers were astonished at the freedom that mid-Victorian unmarried upper-class girls enjoyed, often going shopping or for walks with young men without chaper-ones. Some got the reputation of being fast, surreptitiously smoking and engaging in equivocal allusions to sex. American girls, who were less boring, more animated and independent, were in fact more prudish. On the other hand, a girl lost her freedom when she married, whereas in France she gained it. Tolstoy noted in Anna Karenina that the upper classes in Britain gave their daughters independence in choice so that they could marry for affection, not for convenience. But Mason overlooks the importance of the dowry and where it came from. Yes, the aristocracy married neither courtesans nor actresses nor the daughters of steel magnates and merchants: a banker’s daughter possibly, but land was always preferable in making an alliance.

Mason locates classic Victorianism, as might be expected, in the middle classes. Yet Dickens and Carlyle shocked Emerson in 1848 by agreeing that “chastity in the male sex was as good as gone in our times, and in England so rare that they could name all the exceptions.” This may have been the equivalent of locker-room talk, but one misses in Mason’s account an analysis of what went on among the intelligentsia and in bohemia, the world of the Rossettis. How widespread was the homosexual community and what of the intense friendships between women?

Advertisement

There are all too few personal accounts of what went on in bed even among the intellectuals and artists. Mason refers to two well-known mid-Victorian diaries but admits that neither could be said to be typical. The first is by the anonymous author of My Secret Life, 1 “Walter,” a sexual athlete who needed to ejaculate at least twice a day and who surpassed with ease Don Giovanni’s one thousand and three in Spain. The other was by Arthur Munby,2 a barrister and archetypal bachelor who was obsessed by working-class women and the clothes they wore: the filthier the work—and hence the clothes—of colliery girls or mudlarks the more he doted on them. (I remember G.M. Trevelyan’s mild surprise when he opened the Munby papers in Trinity College Library after the expiry of the embargo, and there tumbled out the photographs of three hundred such women.) But doting was all he did. Though he married his cook, he never, so it appears, had intercourse with her or any of the others. His interest was not sexual, not even sociological: it was compassionate. Whereas the insatiable Walter had reason to think that many of the factory women and servants “when not working thought more about fucking than anything else,” Munby was stimulated only by them as workers and by the skill and endurance they displayed. His marriage seems to have been a blissful one: she learned French and he taught Latin at the Working Women’s College. But he was unable to break with social conventions and acknowledge her as his wife.

Mason has similar problems the further he goes down the social scale. He plunges into the thickets of demographic statistics: fertility rates, parish-register evidence revealing illegitimacy rates and early or late marriage. The decline in the marriage rate in the early years of the century was reversed in the 1840s, and it was not until the 1870s that the rate again declined. From mid-century on there was a tendency to marry younger. Between 1830 and 1860 one third to a half of the brides went pregnant to the altar: but that was because the husband wanted to be certain he would have a fertile wife, and many illegitimate babies were conceived in expectation of marriage.

The trouble is that the statistics are often inadequate and variations in occupations, between north and south, rural and urban families are inevitable. For instance miners and agricultural workers had high rates of fertility, but did women in factories have more or fewer children? Demographers disagree. Illegitimate births declined well before legitimate births and, since few among the working class would practice coitus interruptus, Mason argues that other forms of birth control were being practiced on a wide scale. In the second half of the century a condom cost only a halfpenny. They were used in working-class families though less frequently than the pessary and douche. Advocates of birth control like Annie Besant toured the country lecturing; but most of the uneducated learned about birth control through advertisements in urinals and drug stores, and on posters. After 1877 when Besant stood trial for advocating birth control and was acquitted, manufacturers launched a sales drive. Mason reasons that abstinence did not find favor with wives and quotes one from York saying “Self-restraint? …Not much! If my husband started on self-restraint, I should jolly well know there was another woman in the case.”

The Victorians lived when the population was soaring, and they also lived under the shadow of the economist Thomas Malthus, who published in 1798 his celebrated essay arguing that while population rose in a geometrical ratio, subsistence rose only in an arithmetical ratio: misery and vice were therefore the lot of mankind, and hunger was as natural as lust. Malthus stimulated both Darwin and Marx, but some Victorians, such as the utilitarians and the socialist Robert Owen, challenged Malthus’s pessimism. Change living conditions, they said, and sexual behavior will change. Conservatives scoffed that even if a loaf cost a penny more working-class men would have their wives just as often. The economist Nassau Senior talked much better sense when he said that what controlled marriage rates was the desire for the decencies of life—better living quarters, not having to share a bed with one’s sons and daughters, and social standing.

What then should your attitude be toward sensuality? Were you for or against it, did you believe restraint could be practiced and, if so, was it good or bad for your health? The rationalist W.R. Greg regarded celibacy as a “social gangrene.” The Reverend Charles Kingsley celebrated the joys of physical lovemaking with his wife; but if it was so enjoyable, how on earth could frailer creatures be restrained? So although the Anglican clergy deplored celibacy—a Roman practice—they backed restraint and later marriage, and deplored sensuality. On this the high-minded agnostics, such as George Eliot, were their allies. Sex became a subject of elevated debate among physicians, athletic coaches, and professional moralists. Did those deprived of sexual experience, such as spinsters, run a risk to their health? Per contra were men who experienced nocturnal emissions or forced their wives to submit night after night weakening their other powers? Was the Cambridge crew right to declare that a man rowed better if he refrained from sex?

Advertisement

Contrary to the assertion made by some writers, there was, as Mason argues, no priesthood at the top of the medical profession dictating to practitioners what to believe. For instance, George Drysdale, a precursor of Havelock Ellis, argued during the 1880s that sexual abstinence could cause lesions in the sexual organs. He did something to offset the influence of William Acton, the man usually cited as the typical Victorian physician, whose most notorious dictum was that “the majority of women…are not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind”; and hence prospective husbands need not fear that they will have to develop an erection night after night. Yet elsewhere, Mason notes, he gave a contrary indication when he spoke of the “efficiency” of the penis. In fact Acton’s denunciation of masturbation and sexual excess was less fantastic than Drysdale’s caricature of the evils of abstinence.

Mason then puts forth an interesting paradox. Doctors did not rule their patients and play upon their imaginations with dire warnings. On the contrary, their patients ruled them. The medical profession was oversubscribed and underpaid. They were frightened of their patients leaving them for another doctor. One thinks of Lydgate in Middlemarch whose patients desert him because he refuses to dispense drugs and asks instead for a fee. Nor do matters improve when he diagnoses at the hospital and cures a patient of a cramp that another practitioner had declared was a tumor. George Eliot wrote that Lydgate, progressive though he was, did not enter “into the nature of diseases [which] would only have added to his breaches of medical propriety.” Doctors rarely told their patients what they had diagnosed. They did not want to upset their patients’ own beliefs. For instance there was a theory that women ovulated each time they had an orgasm, that they knew instinctively this was the case and for fear of conceiving held off. Mason denies that Victorian women were ignorant or joyless, but he admits that many doctors were opposed to birth control, and they were enraged when Bertrand Russell’s father declared in 1868 that they ought to favor it. They were too scared of a charge of impropriety to make a vaginal examination.

They also feared their patients would desert them for quacks—and on sexual matters quacks abounded. Men went to them in their thousands. A new disease was invented—spermatorrhoea: simply the tendency to have an excessive amount of sperm. Was a nocturnal emission a symptom of this? Was continence or masturbation the cause? If sexual intercourse was a healthy activity, were continent bachelors at risk? These were the anxieties that doctors did little to dispel; and they were heightened by the moral codes taught in the churches, the public schools and the army in which promotion was blocked for years and an officer usually could not afford to marry until his late thirties.

Victorian hypocrisy is supposed to have reached its height in accepting mass prostitution. Writing early in the century, the great reformer and socialist Cobbett thought the growth of factories increased prostitution in provincial cities. But Francis Place argued that in the second and third decades of the century the new police force and town-clearance schemes disrupted and reduced the trade. When Trafalgar Square was created in 1815, the brothels of Charing Cross were pulled down—though some would argue that the trade merely moved east to the Strand and west to the Haymarket. The Victorians did not see prostitutes as scum on the surface of society. They saw them as souls to be saved from ruin. How many prostitutes were there? The police put the figure at 30,000, but, according to Mason, members of the public, when asked, reckoned there were half a million. Yet in fact the proportion of prostitutes to population was all the time declining.

Mason has kept for a later volume the influence of religious sects upon Victorian sexuality, but there is too little mention of it here—hardly a reference to Methodism with its roots in the mid-eighteenth century or to the Evangelical movement already in full swing at the turn of the century. Methodism had a deep effect upon working-class culture. Many prostitutes learned that they were more likely to prosper if they appeared demure, well-dressed, and even respectable than if they seemed strident and brazen. Mason cites many references to improvements in their manners: in 1850 an American visitor landing in Liverpool thought the sailors’ “wives” were positively neat and quiet. So much did the tone rise that some middle-class women preferred to travel by rail third class to avoid being accosted in first-class carriages.

Then as now prostitution was a way to better oneself. Thomas Hardy knew the ironies of prostitution and wrote a poem in 1866 about the amazement of the Dorset girl when she meets in London her former companion who used to pick turnips with her and who has gone “on the game” in London:

‘O ‘Melia, my dear, this does everything crown!

Who could have supposed I should meet you in Town?

And whence such fair garments, such prosperi-ty?—’

‘O didn’t you know I’d been ruined?’ said she.

Mason’s fascinating book serves to remind us of life’s paradoxes. Factory workers attired in black would behave with total decorum at a singsong arranged by their boss. Yet many in the audience would enjoy an evening at the Cider Club or at the Coal Hole, where bawdy songs were sung. A dialectic seems at work. No sooner does prudery take over than the safety valve blows. The innocent love songs at these dives were ousted after 1850 by “Lamentation of a Deserted Penis.” So it is in our own times when having a very active sex life has for years been approved and admired, and anyone who defined the norm as “moderate intercourse in marriage” would be ridiculed. The century-long revulsion against Victorian prudery has created a counterforce in feminism. New prohibitions such as sexual harassment have emerged. We shudder perhaps more than ever at rape and the seduction of children; and the press teems with reports of child abuse by fathers.

It is especially interesting to see how, in Victorian times, not only the Evangelicals but the progressives deplored sensuality. Putting their trust in rational codes of conduct, they regarded sensuality as a force so unpredictable and disturbing that, if unleashed, it could upset the tidy, planned world of the future. In the 1850s, the first secretary of the Social Science Association wanted society to be like a “well-run reformatory school,” subject to “moral and religious discipline, combined with good sanitary arrangements, and a proper union of industrial and intellectual education.”

To leave Michael Mason’s sober study for the pages of Theo Aronson’s preposterous book is to exchange scholarship for fantasy. If there was one circle in Victorian times which was not like a well-run reformatory school it was the Prince of Wales’s set. The eldest son of the Prince of Wales who later became King Edward VII, and therefore Heir Presumptive to the British throne, was known as Prince Eddy. He died of pneumonia in 1892, and it was his younger brother who succeeded to the throne as George V. Not even the most stalwart supporters of monarchy can find much to say in Prince Eddy’s favor. He was a vacuous, unintelligent youth, who, like his father, never read a book.

But it was worse than that. Nothing seemed to interest him. He was lethargic, apathetic, incompetent, a clothes-horse, a dandy in his Hussars uniform whom his father chaffed mercilessly and nicknamed “Collar and Cuffs.” A photograph of him in a kilt, fishing rod in hand, makes one doubt that he could ever land a trout. His elderly cousin the Duke of Cambridge was in despair on the parade ground: Prince Eddy could not learn the simplest movements in drill or words of command. In Dublin during the ceremonies the Viceroy had to prompt him. “Get up,” “Kneel down.” He reminds us of P.G. Wodehouse’s young Motty in New York, who sat sucking the nob of his elegant cane, occasionally uncorking himself to answer his mother before corking himself up again.

It will be remembered, however, that Bertie Wooster found that the inane Motty was a devil when let loose on the town, returning sozzled night after night. So it was with Prince Eddy. He was unaffected, unpompous, and affectionate toward his friends. His servants were devoted to him. But Sir Philip Magnus and Georgina Battiscombe, the biographers of his parents, declared that he was “dissipated and unstable”; and that as time passed “his dissipation began to undermine his health.” Even his doting mother Princess Alexandra once spoke of him as a “naughty bad boy.”3 “Dissipation” was a term used in those days to mean too decided a taste for chorus girls and champagne. His contemporaries saw him that way—the Prince, one of them said, “could hear the rustle of a pair of silk knickers four rooms away.” But that will not do for Theo Aronson. There must be more to it than whores and drink. Prince Eddy must have been a homosexual.

How does he establish this as a fact? By pages and pages of innuendo. At the age of thirteen Eddy and his brother joined the naval training ship Britannia. Well, everyone knows that Churchill defined the traditions of the Royal Navy as rum, sodomy, and the lash. Their tutor, John Dalton, saw to it that “his charges were kept sexually uncorrupted.” But surely Eddy experienced “the obscenities and ribaldries of shipboard life.” Then, sent to Cambridge, he mixed with men who were already, or became, homosexual, like Lord Ronald Gower, or the absurd don Oscar Browning, who was once locked in a room with Prince Eddy as an undergraduate prank. What the two did “no one knew.” Whether in Cambridge Eddy experienced his first sexual encounter, “one can only speculate.” Worse still, Virginia Woolf’s cousin J.K. Stephen was his mentor. Stephen wrote sardonic light verse (some of it funny); on the basis of one stanza Aronson convicts him of being a venomous misogynist.

Aronson then resurrects two scandals already worked to death by journalists, in which Prince Eddy’s name surfaces. But first he examines whether the Prince contracted a secret marriage. In 1973 Joseph Sickert, an illegitimate son of Walter Sickert, the painter, claimed on the BBC that he was the grandson of Prince Eddy, who had married a woman from a tobacconist’s shop (the traditional place where sprigs of the aristocracy contracted misalliances). The affair was hushed up, he said, and Queen Victoria’s physician, Sir William Gull, operated on this woman, deliberately maiming her mentally for life. Aronson admits that the story of Prince Eddy’s secret marriage is “an amalgam of rumours, inferences, coincidences and contradictions…entirely lacking in any hard evidence.” But should we not look at it more carefully? According to Joseph Sickert this secret marriage was the motivation for the first scandal, the Jack the Ripper murders.

Jack the Ripper was a serial murderer who in 1888 killed six prostitutes, eviscerating them and ripping out their sexual organs. In 1970 T.E.A. Stowell published an article in the Criminologist suggesting that Prince Eddy was the Ripper. How this listless and feeble creature could have had the strength to rip up prostitutes is far from clear, and in any case the Court Circular shows that he had an alibi for every night on which the women were murdered. However, a series of amateur sleuths got to work, writing articles for the London press. Frank Spiering repeated the story and argued that J.K. Stephen covered up the evidence for love of Prince Eddy. Not so, said Michael Harrison, J.K. Stephen himself was the Ripper. Rubbish, replies Joseph Sickert. Sir William Gull was the guilty man: he murdered as part of a Masonic conspiracy. Martin Howells and Keith Skinner were less sensational. The Ripper was a man called Druitt, who committed suicide. At all events, after his death the hunt for the Ripper was called off.

Why? A cover-up of course. It would have been found that Druitt was a friend of Harry Wilson, an intimate friend of Prince Eddy from Cambridge days, and a member of a homosexual clique. This cover-up, says Aronson, is suggestive. It was the prelude to a far more notorious coverup next year of the second great scandal—the Cleveland Street affair.

The police had uncovered a male brothel in that street, and in the course of interrogating the telegraph boys who were procured for clients, discovered that Lord Arthur Somerset was a frequent visitor. Lord Arthur was the third son of the Duke of Beaufort. His second son had already gone abroad after being divorced for his gay liaisons (his wife was a cousin once removed from Virginia Woolf). However, after the police put forward the case for bringing Lord Arthur to trial, the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Attorney General, the Home Secretary, and the Prime Minister himself all delayed and prevaricated. Meanwhile Somerset and his solicitor were busy paying possible witnesses to emigrate.

Somerset was a member of the Prince of Wales’s set and the Prince refused to believe the rumors about “poor Podge.” But after a number of discreet meetings the Prime Minister let the Prince of Wales’s comptroller know that there was a possibility that Somerset might be arrested. The Prince of Wales was thunderstruck; surely it was a case of mistaken identity? Tipped off, Somerset fled to France. The future Edward VII was a loyal friend and had an underling ask whether proceedings against Somerset could be dropped. But surely, says Theo Aronson, there must have been a stronger reason than mere concern for the Beaufort family, whose sexual record was so equivocal. The reason must have been that Prince Eddy’s name was mentioned as being involved.

Meanwhile the radical press had got onto the affair, and one editor declared that Lord Euston, the heir to the Duke of Grafton, also frequented Cleveland Street. Euston sued and cleared his name; and the editor was sent to jail for criminal libel. But why were certain crucial witnesses not brought forward? And why was the principal witness for the prosecution, a male prostitute, not put on trial for perjury? By the end of 1889 the London correspondent of The New York Times reported that there was a “general conviction” that Prince Eddy was implicated. Eddy had, in fact, been on an official tour of India throughout the scandal. But new twists were added to the rumors. Had Lord Arthur Somerset sacrificed himself to shield the Prince? His sister denied that “Arthur and the boy ever went out together.” But was not Somerset’s solicitor put on trial for perverting the course of justice by spiriting witnesses out of the country? Why did the prosecution fail to press the case harder, letting the solicitor off with only six weeks’ imprisonment?

Why was it indeed that the Establishment, led by the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, a man of the utmost sagacity, was so keen to cover up Somerset’s activities (and possibly Euston’s as well)? Aronson declares that there can be only one reason. The Crown was endangered by Prince Eddy’s complicity. Yet the reader who has not been bludgeoned into agreement by the continuous innuendo will notice that there is only one piece of testimony that Prince Eddy was homosexual; and that is hearsay. Years later, in 1949, the Lord Chief Justice, Rayner Goddard, told Harold Nicolson when he was writing the life of George V that Prince Eddy “had been involved in a male brothel scene, and that a solicitor had to commit perjury to clear him.”4 Goddard, it will be noted, got the facts wrong. The only firm evidence we have of Prince Eddy’s “dissipation” is that he shared a mistress in St. John’s Wood with his brother, who described her as a “ripper.”

Any unmarried prince of the British royal family is likely to be rumored to be homosexual; and it was hardly possible for Prince Eddy not to be acquainted with those in the upper classes who were so. When the Queen and Prince Eddy’s father decided that the time had come for him to marry, he made no objection. The first choice refused him—and was later as Tsarina of Russia executed by the Bolsheviks. And then he fell in love with a girl who was out to get him, Princess Hélène d’Orléans. Unfortunately she was not only a Roman Catholic but the daughter of the exiled claimant to the French throne; and the Prime Minister told the Palace that this would not do. He was then betrothed to Princess Mary of Teck but died before the wedding. She later married his brother George V.

Death did not quench the rumors. They multiplied. He was not dead, but had been spirited away to a sanitorium. Lord Randolph Churchill had been deputed to murder him. But Joseph Sickert was at hand with a more gothic explanation, which links him to the more mundane affairs of the royal family today. The Prince, he said, was confined to Glamis Castle, the childhood home of Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, a castle already renowned as having harbored for years a monster. There he lived, painting. To prove it Sickert produced a photograph (rejected even by Aronson) of a man sitting beside an easel showing a lot of cuff.

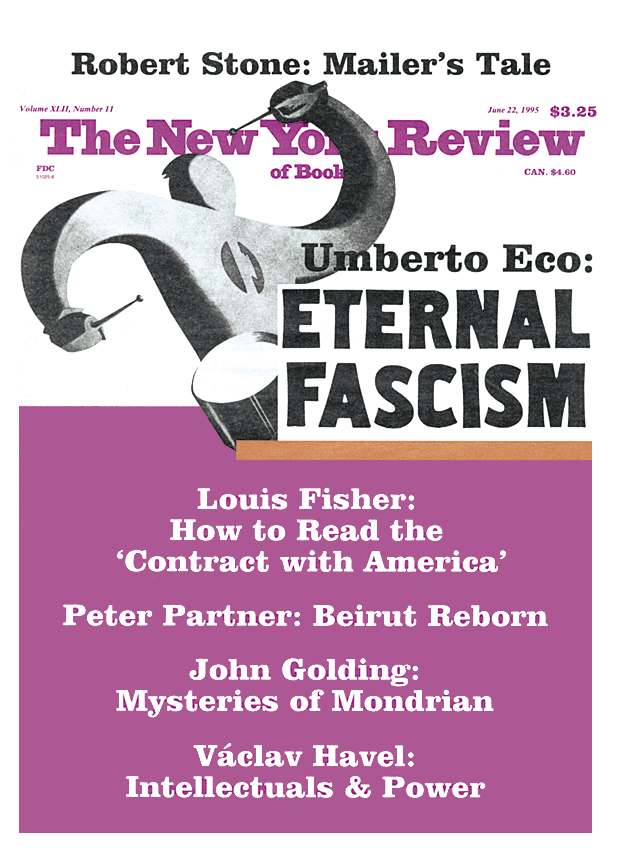

This Issue

June 22, 1995

-

1

My Secret Life (1916) (Grove Press, 1966). ↩

-

2

Derek Hudson, Munby: Man of Two Worlds (Gambit, 1972). ↩

-

3

Philip Magnus, King Edward the Seventh (Dutton, 1964); Georgina Battiscombe, Queen Alexandra (Houghton Mifflin, 1969). ↩

-

4

The remarks of a senior law officer may be regarded by some as convincing, but Goddard may simply have been retailing the gossip of his generation. He was a bitter opponent of the legislation passed by Parliament to make homosexual acts between consenting adults no longer criminal, and warned the House of Lords of the existence of “buggers clubs.” He later told Lord Arran, the promoter of the bill, that none of the letters he received gave support for his views: all asked for the addresses and telephone numbers of the clubs. ↩