“That was when he felt his entire structure of organized thought begin to slide slowly toward some dark abyss.”

—Stephen King, The Langoliers

Stephen King has become a household name in at least three senses. He is a writer pretty much everyone in the English-speaking world has heard of, if they have heard of writers at all. He is regularly read by many people who don’t read many other writers. And, along with Danielle Steel and a few others, he is taken to represent everything that is wrong with contemporary publishing, that engine of junk pushing serious literature out of our minds and our bookstores. The English writer Clive Barker has said, “There are apparently two books in every American household—one of them is the Bible and the other one is probably by Stephen King.” I don’t know what Barker’s source is for this claim, but I wonder about the Bible.

Do we know what popular literature is? When is it not junk? Is it ever (just) junk? Who is to say? What is the alternative to popular literature? Serious, highbrow, literary, or merely…unpopular literature? Stephen King responded with eloquent anger in an argument over these issues conducted in the PEN newsletter in 1991. He thought best-selling authors came in all kinds. He said he found James Michener, Robert Ludlum, John le Carré, and Frederick Forsyth “unreadable,” but enjoyed (among others) Elmore Leonard, Sara Paretsky, Jonathan Kellerman, and Joyce Carol Oates. This seems sound enough to me, although I have to confess to liking Ludlum and le Carré as well. “Some of these,” King continued, “are writers whose work I think of as sometimes or often literary, and all are writers who can be counted on to tell a good story, one that takes me away from the humdrum passages of life…and enriches my leisure time as well. Such work has always seemed honorable to me, even noble.”

What had made King angry was the term “better” fiction, which Ursula Perrin had used in an open letter to PEN (“I am a writer of ‘better’ fiction, by which I mean that I don’t write romance or horror or mystery”) complaining about the profusion of worse fiction in the bookstores—“this rising sea of trash” were her words. “Ursula Perrin’s prissy use of the word ‘better,’ ” King says, “which she keeps putting in quotation marks, makes me feel like baying at the moon.” Perrin’s examples of writers of “better” fiction were John Updike, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., and Alice Hoffman.

But King was wrong, I think, to assume that Perrin’s argument could rest only on snobbery, and he himself owes his success not to some all-purpose skill in entertainment but to his skill in a particular genre, and to his readers’ expectations of that genre. There is a real difficulty with the rigidity and exclusivity of our literary categories; but it is no solution to say that exclusivity is the problem. What happens perhaps is that the tricky task of deciding whether a piece of writing (of any kind) is any good is repeatedly replaced by the easier habit of deciding which slabs or modes of writing we can ignore. Even King, who not only should but does know better, confuses fiction that is popular with popular fiction, best sellers with genres, and his line about the humdrum passages of life and the enrichment of leisure time is as condescending in its mock-demotic way as the idea of “better” fiction. No one would read Stephen King if that was all he managed to do.

Genres do exist, however we name them, and the work they do is honorable, even noble. When we say writers have transcended their genre, we often mean they have abandoned or betrayed it. Genres have long and complicated histories, richer and poorer, better and worse. They may be in touch with ancient and unresolved imaginative energies, or whatever haunts the back of a culture’s mind; and they permit and occasionally insist on allusions the writer may have no thought of making. Stephen King, however, has thought of making allusions, and thought of it more and more, as the excursions into classical mythology of Rose Madder make very clear.

What’s interesting about Carrie,1 King’s first novel, published in 1974, is the way it sustains and complicates its problems, gives us grounds for judgment and then takes them away. The genre here (within the horror genre) is the mutant-disaster story, which in more recent years has become the virus novel or movie. Sixteen-year-old Carietta White has inherited aweinspiring telekinetic powers, and in a fit of fury wipes out whole portions of the Maine town where she lives, causing a death toll of well over four hundred. Carrie has always been awkward and strange, cruelly mocked by her companions at school, and liked by no one. Her mother is a morbid fundamentalist Christian who thinks that sex even within marriage is evil. The town itself is full of rancor and hypocrisy and pretension—the sort of place where the prettiest girl is also the meanest, the local hoodlums have everyone terrorized, and the assistant principal of the school has a ceramic ashtray in the form of Rodin’s Thinker on his desk—so that without any supernatural intervention at all there’s plenty to go wrong, and plenty of people to blame. Carrie’s terrible gift for willing physical destruction is an accident, the result of a recessive gene that could come up in anyone, and the novel makes much play with the idea of little Carries quietly multiplying all over the United States like bombs rather than children. The last image in the novel is of a two-year-old in Tennessee who is able to move marbles around without touching them, and this is the portentous question the novel pretends to address: “What happens if there are others like her? What happens to the world?”

Advertisement

This is a big question, but it’s not as important as it looks, because apart from being unanswerable in the absence of any knowledge of the characters and lives of the “others like her,” it mainly serves to mask another question, which is the most urgent question of the horror genre as Stephen King practices it: What difference does the supernatural or fanciful element make, whether it’s telekinesis or death-in-life? What if it’s only a lurid metaphor for what’s already there? Carrie White is not a monster, even if her mother is. Carrie has been baited endlessly, and when someone is finally nice to her and takes her to the high-school prom, the evening ends in nightmare: pig’s blood is poured all over her and her partner, a sickening echo and travesty of the opening scene in the novel, where Carrie discovers in the shower room that she is menstruating and doesn’t know what’s happening to her. Human folly and nastiness take care of this entire region of the plot, and Carrie’s distress and rage are what anyone but a saint would feel. But then she has her powers. The difference is not in the rage but in what she can do about it, and this is where contemporary horror stories, like old tales of magic, speak most clearly to our fears and desires.

Edward Ingebretsen, S.J., in an interestingly argued book whose subtitle confirms King’s status even in the academic household,2 speaks of religion where I am speaking of magic. “Once-religious imperatives,” he says, “can be traced across a variety of American genres, modes, and texts.” “The deflective energies of a largely forgotten metaphysical history live on, not only in churches, but in a myriad other centers of displaced worship.” Ingebretsen has a nice sense of irony—I hope it’s irony—dark and oblique like his subject: “A major comfort of the Christian tradition is the terror it generates and presupposes….” He certainly understands how King, while seeming to offer escape from the humdrum passages of life, shows us the weird bestiary lurking in those apparently anodyne places. “Change the focus slightly and King’s horror novel [in this case Salem’s Lot] reintroduces the horrific, although the horrific as it routinely exists in the real and the probable.” “Routinely” is excellent.

It’s true that religious hauntings are everywhere in American life, but because they are everywhere, they don’t really help us to see the edge in modern horror stories, the way these stories suggest that we have returned, on some not entirely serious, not entirely playful level, to the notion that superstitions are right after all, that they offer us a more plausible picture of the world than any organized religion or any of our secular promises. It’s not only that the old religion is still with us, but that even older ideas have returned to currency. This is a very complicated question, but the notion of magic will allow us to make a start on it.

Magic is the power to convert wishes into deeds without passing through the cumbersome procedures of material reality: taking planes, hiring assassins, waiting for the news, going to jail. It bypasses physics, connects the mind directly to the world. All of Stephen King’s novels that I have read involve magic in this sense, even where nothing supernatural occurs, where the only magic is the freedom of fiction to move when it wants to from thought to act. Would you, if you could, immediately and violently get rid of anyone and anything you dislike? If you were provoked enough? And could be sure of getting away with it? The quick response, of course, is that you know you shouldn’t, and probably wouldn’t. The slow response is the same, but meanwhile, if you’re not really thinking about it, you probably let it all happen in your head, which is a way of saying yes to the fantasy of immense violence while feeling scared about it.

Advertisement

This must be a large part of the delight of this kind of horror fiction. Is this really all right, even in a novel? There’s a relish in the thought of Carrie’s destroying her miserable town; we can’t wait for another gas station to blow up. But there’s also an ugly comfort in feeling Carrie’s an alien and a freak, not one of us, and above all in knowing, at the end, that she’s dead. At the heart of Carrie is a conversation between Susan, the one girl in town who worries about Carrie, and Susan’s amiable boyfriend, who dies for his attempt at niceness. They have no idea of what’s going to happen; they know only that everyone’s always been mean to Carrie.

“You were kids,” he said. “Kids don’t know what they’re doing. Kids don’t even know their reactions really, actually, hurt other people….”

She found herself struggling to express the thought this called up in her, for it suddenly seemed basic, bulking over the shower-room incident the way sky bulks over mountains.

“But hardly anybody ever finds out that their actions really, actually, hurt other people! People don’t get better, they just get smarter. When you get smarter you don’t stop pulling the wings off flies, you just think of better reasons for doing it.”

And what if, the question about magic continues, you grant to these people, without improving their moral awareness in any significant degree, inconceivable powers to hurt? To wipe out cities or abuse their wives? It wouldn’t matter whether you called these powers telekinesis or Mephistopheles. Carrie’s relative innocence—she’s not smart and she doesn’t pull the wings off flies—helps to focus the question but makes the powers all the scarier. Fortunately it’s only a fantasy.

If we want to see what a genre novel looks like when it’s barely in touch with any imaginative energies, either ancient or modern, we can look at King’s The Langoliers, a short work published in Four Past Midnight,3 and recently adapted as a lumbering miniseries for ABC. The genre here is the end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it story, combined with a disaster in technology (airplane, ocean liner, sky-scraper). A plane leaves Los Angeles and flies through a fold in time into the past—or rather into an alternative world which the present has abandoned, into the past as it would be if it vanished the moment we turned our backs on it. The plane lands at Bangor, Maine, which turns out to be deserted, nothing but stale air and tasteless food. The plane manages miraculously to refuel and to fly back through the time fold. There is a nasty moment when it arrives in Los Angeles too early—this is the future, and just as deserted as the past, but not as dead and tasteless. The good news is that you only have to wait a while for the present to get here.

There are possibilities here, and the hint of a genuine anxiety about the fading past, a sort of mixture of disbeliefs about it: that it’s still there, that it’s actually gone. King writes engagingly in his introduction of “the essential conundrum of time”—“so perfect that even such jejune observations as the one I have just made retain an odd, plangent resonance”—but he hasn’t worked all that hard at this version of it, and obviously felt his novel needed something more, which he provided in the shape of huge bouncing balls which are eating away at the earth—well, not just the earth, but reality itself. The balls are black and red, they have faces and mouths and teeth; they are “sort of like beachballs, but balls which rippled and contracted and then expanded again….” “Reality peeled away in narrow strips beneath them, peeled away wherever and whatever they touched….” Apart from telekinesis, King has written about vampires, rabid dogs, cats back from the dead, zombies, a demon automobile, and a whole barrage of ghosties and ghoulies. But sort of like beach-balls?

The novel and the movie called Dolores Claiborne are good illustrations of the way in which the same story can be told twice and mean different things each time. The novel is all about what people do when there’s nowhere to go. The movie is about doing what you can but still having nowhere to go, and every image in it—the sea and the sky, the bare landscape, the half-abandoned houses—reinforces this feeling. I don’t think the movie intends to be depressing. It intends to be beautiful and uplifting, all about courage and coming through, and Kathy Bates, as Dolores Claiborne, is full of fight and dignity. But she can’t compete with all those images, which in another context might well suggest freedom or an unspoiled world.

Still, it is the same story, in spite of the different tilts of meaning and of obvious and extensive changes in the development of characters and their part in the plot. Dolores Claiborne, accused of two murders, has committed one but not the other. In the second case, where she is innocent, the evidence is damning. She was seen with a rolling pin raised above the head of the aged and now dead woman whose housekeeper she was, and she has inherited a fortune through the woman’s death.

In the first case, when she killed her husband nearly thirty years ago, the evidence was sparse because she took care to get rid of most of it—of all of it that she could find. She killed him, not just because he was a drunk and because he beat her, and not just to be free of him, but because he was molesting their daughter, and she could see no future for any of them in the world as long as he was alive. Obliquely but unmistakably instructed by her employer (” ‘An accident,’ she says in a clear voice almost like a schoolteacher’s, ‘is sometimes an unhappy woman’s best friend.’ “), Dolores arranges for her drunken husband to fall down an old well he can’t get out of. Like all bad characters in good horror stories, he takes a long time dying, indeed seems virtually unkillable. The same trope animates the battered and dying bad guy in The Langoliers; “There was something monstrous and unkillable and insectile about his horrible vitality.”

This may remind us that murder in fiction is always too easy or too hard—that it is a fiction, a picture not of killing but of the way we feel about killing. Will Dolores, guilty the first time, get convicted the second time? Will her daughter, who suspects her of murder, ever trust her again? Would her daughter understand if she heard the whole story? Both the novel and the movie answer these questions, and both use the total eclipse of the sun in 1963 as their dominant visual image. This is the day of the murder of the husband, ostensibly a good time to get away with it, but really (that is, figuratively) a time of strange darkness when all bets are off and all rules suspended: this is the magic of the story, the moral telekinesis. Dolores doesn’t need supernatural aid to kill her husband, she just needs, magically, for a few hours, to be someone else.

We are back in the world of Carrie, where rage is both understandable and terrifying. Carrie can read minds as well as move objects, and a phrase used about her helps us to see something else these novels are about: “the awful totality of perfect knowledge.” The novels don’t have perfect knowledge, or imagine anyone has it, except by magic. But then the magic, as well as giving anger a field day, would also give us a glimpse of the inside of anger, as if we could read it, as if it could be perfectly known. We might then want to say, not that to understand everything is to forgive everything, but that to understand everything is unbearable.

Stephen King is still asking his question about magic in Rose Madder, his most recent novel. It takes two forms here, or finds two instances. One involves a psychopathic cop, Norman Daniels, addicted to torturing his wife but shrewd enough to stop before she dies or before the evidence points only to him. He is also a killer, but even his wife doesn’t know how crazy he is until she leaves him. Yet he’s thought to be a good guy down at the station, recently promoted for his role in a big drug bust. His wife thinks every policeman is probably on his side, if not actually like him. Until King introduces a good cop around page 300, it looks as if the police force itself is the psychopath’s version of telekinesis, what moves the world for him. There is a disturbing moment at the beginning of the novel, borrowed from Hitchcock but subtly and swiftly used, when Norman, having beaten his wife badly enough to cause a miscarriage, decides to call the hospital. “Her first thought is that he’s calling the police. Ridiculous, of course—he is the police.”

The other, more elaborate form of the question concerns Norman’s wife, Rose. She finally finds the nerve to run away, after fourteen years of what King describes as sleep:

The concept of dreaming is known to the waking mind but to the dreamer there is no waking, no real world, no sanity; there is only the screaming bedlam of sleep. Rose McClendon Daniels slept within her husband’s madness for nine more years.

Rose starts a new life in a distant city; makes new friends, gets a job reading thrillers for a radio station. You will have guessed that Norman goes after her and catches up with her at the climax of the novel, and that there is much maiming and murder and fright along the way, and you will have guessed right. The violence is inventive and nasty, and Norman is as truly scary a fictional character as you could wish to keep you awake at nights. He owes a certain amount to the Robert De Niro character in Taxi Driver, but when King himself refers to the actor and the movie—he pays his dues—the gesture isn’t merely cute, it’s amusing and polite, a casual tip of the hat. Norman is madder than the De Niro figure, his murder score is much higher, and—this is really distressing—he is often funny. Norman glances at a picture of Lincoln, for example, and thinks he looks “quite a bit like a man he had once arrested for strangling his wife and all four of his children.”

What you won’t have guessed is that the novel has a classical streak, and that King is quite consciously connecting his own modern mythology to a well-known ancient one. Rose buys a painting—it’s called Rose Madder, after the color of the dress of the woman who is the chief figure in it, but the title, for us, also plays on the double meaning of “mad,” on Rose’s need to get angry and the craziness that may result—and discovers that she can step into it, become part of its world and have adventures there. The picture appears to be a rather banal classical landscape, with a ruined temple, and vines, and thunderheads in the sky. What’s going on there, as Rose learns when she visits, is a mixture of the myths of the Minotaur in the maze and of Demeter looking for Persephone, her daughter by Zeus, after Persephone has been abducted into the underworld.

The creature in the maze isn’t exactly the Minotaur, since it’s all bull, and it’s called Erinyes, a name which means fury, and is one of Demeter’s epithets. Later the bull becomes Norman, or Norman becomes the bull: the monster is a metaphor for the less-than-human male. It’s an engaging feature of King’s play with these images that he doesn’t forget the risks he’s taking, and when Rose sees a pile of creaturely crap in the mythological maze she knows what it is: “After fourteen years of listening to Norman and Harley and all their friends, you’d have to be pretty stupid not to know bullshit when you see it.”

The mother seeking her child is not exactly Demeter either, since Rose is told the mother is “not quite a goddess,” and Demeter was undoubtedly the real thing. The mother is also decaying, having “drunk of the waters of youth” without getting immortality to go with it; and she is not exactly, or not always, a woman. She is a feminine principle, Carrie’s rage in a calm disguise, telekinesis in a classical garb, and sometimes she looks like a spider or a fox. A literal vixen and cubs introduced in another part of the novel—in the world which is not that of the painting—set up the idea of rabies, whose name means rage, and whose name is rage in several European languages. “It’s a kind of rabies,” Rose thinks, picturing some mythological equivalent of the disease, a consuming anger which could destroy a near goddess. “She’s being eaten up with it, all her shapes and magics and glamours trembling at the outer edge of her control now, soon it’s all going to crumble….”

This woman is a figure for the anger Rose may not be able to control or return from. The last pages of the novel are like an afterword to Carrie. Rose knows the power of her anger, but her anger also knows her, and won’t let her go. In a trivial quarrel in her happy new life, after the gruesome and entirely satisfactory mangling of Norman in the spooky world of the painting—not only in that world, though, Norman’s not coming back—Rose has to make “an almost frantic effort” not to throw a pot of boiling water at her harmless second husband’s head. She finds peace in an encounter, not with the near goddess of the picture, but with the vixen of the American countryside, with the puzzle of rabies in that clever female face. “Rosie looks for madness or sanity in those eyes …and sees both.” But only sanity is actually there—a matter of luck, no doubt, of the way the disease ran among the local wildlife—and when she sees the vixen much later, Rose has become confident of her own resistance to the power to hurt, knows the madness (or the magic) has faded. These are the last words of the book: “Her black eyes as she stands there communicate no clear thought to Rosie, but it is impossible to mistake the essential sanity of the old and clever brain behind them.”

King writes very well at times: “Her shadow stretched across the stoop and the pale new grass like something cut from black construction paper with a sharp pair of scissors”; “Huge sunflowers with yellowy, fibrous stalks, brown centers, and curling, faded petals towered over everything else, like diseased turnkeys in a prison where all the inmates have died.” The second example is a bit ripe maybe, but it’s effective. But then we also get “riding through a dream lines with cotton”; “shards of glass twinkling beside a country road”; “the unforgiving light of an alien sun”; “she…was fearfully enchanted”; and “what she felt like was a tiny speck of flotsam in the middle of a trackless ocean.” This is not popular writing, it’s yesterday’s posh writing, and it’s consistent with Rosie’s thinking of Madame Bovary and Norman’s muttering a line from Hamlet. Perhaps this is “better” fiction after all.

But of course what we are looking for in this novel is not felicity of phrase but invention and dispatch, and racking fictional anxiety, and King supplies them in good measure. He also gives us a pretty generous clue to what he is up to with his mythology. Within the world of the painting the bull gets out of the maze, and Rose worries that this may mean not only that the bull is loose but that the world has become his maze. The world of the painting, at least. A voice in her head, eager to help King out, takes her thought further. “This world, all worlds. And many bulls in each one. These myths hum with truth, Rosie. That’s their power. That’s why they survive.” This is heavy-handed as explanation, but doesn’t really hamper the functioning of the myth. The magical picture of Rose Madder does what the beachballs of The Langoliers just won’t do: reminds us through fantasy how fantastic the unimagined everyday world can be. The trouble, in such a scenario, is not that dreams don’t come true but that we could scarcely live with them if they did. Or that we are already living with them.

This Issue

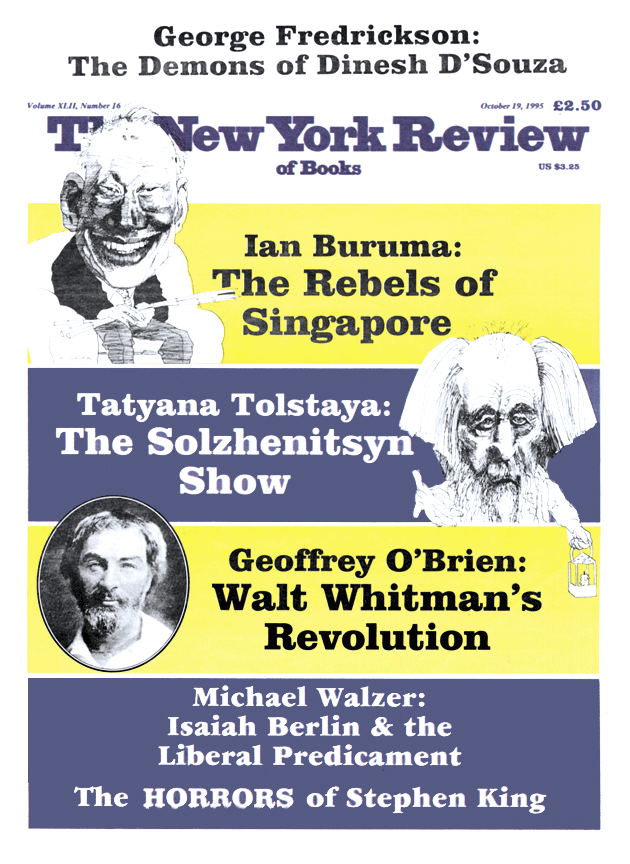

October 19, 1995