1.

And so it finally came to pass, at midnight, June 30, 1997, in the brand-new Hong Kong convention center, resembling, local people say, a giant cockroach: the red flag of the People’s Republic of China, snapping in the breeze of wind machines, went up, and the Union Jack came down. Years, months, days, hours, even anxious last minutes of mind-numbing diplomatic negotiations about protocol had produced an agreement that the sound of God Save the Queen should fade out seconds before the strike of midnight, lest the echoes of the British anthem should spill into the first moments of Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong.

The “homecoming” of Hong Kong has been the most peculiar ending of any colony in modern history. The last colonial governor drifted off into the bay with tears streaming down his cheeks. He was more popular among the people he had governed than the Chinese tycoon who took his place. The freely elected legislature has been shoved aside in favor of “patriots,” appointed by a Communist regime. Most extraordinary of all, a last-minute poll showed that 74.9 percent of the Hong Kong people thought they were better off under British rule, and only 31 percent wanted Hong Kong to be ruled by China. And this doesn’t mean the British were popular.

Under the organized froth of official celebration I detected little sense of joy in Hong Kong. The noisiest revelers on the night of June 30, decked out in dinner jackets and Chinese fancy dress, were foreign and Chinese businessmen, who expect to make a killing. A young Englishman in a Union Jack waistcoat was braying at midnight: “A bit of a hangover tomorrow, and then more money, money, money!”

In the Mandarin Hotel on the morning after, socialites were knocking back champagne to the keening sounds of a Chinese orchestra, while the British grandees who had helped to seal Hong Kong’s fate were heading for their limos to the airport. There was Lord Howe, and there ex-Governor Wilson. After years of publicly undermining Chris Patten’s political reforms, these men demonstrated just what they thought of democracy in Hong Kong by attending the swearing-in of the appointed legislature, even though the top representatives of Britain and the US had decided not to. A leading Hong Kong democrat, sitting gloomily in the downstairs bar, said she was glad it was raining: it would ruin the Chinese celebrations. And she had been one of the most ferocious critics of the British colonial government.

Symbols, clearly, were of the highest importance. To Beijing, the handover of Hong Kong to China was itself a symbolic act—with real consequences, to be sure. The question is, symbolic of what? Several messages were driven home without pause, in official speeches, a new movie, mass stadium demonstrations, newspaper headlines, buttons and badges, T-shirts and posters, and slogans in wooden Chinese: the “homecoming” of Hong Kong was a patriotic victory that wiped out “150 years of shame.” It was as though patriotism should compensate for the lack of independence or democracy. But the homecoming was also hailed as a victory for Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy and his concept of One Country, Two Systems, both of which are now described as the brilliant thoughts of a philosopher-king.

Two days before the homecoming, I was waiting for a friend in the Dining Hall of the Legislative Council (LegCo), one of the very few classical colonial buildings left in Hong Kong. There were three other people in the room: a LegCo member named David Chu, and two American reporters. Chu is a Harvard MBA, a former US citizen, a snappy dresser, a “dangerous sports” enthusiast, and a very rich man. He was giving the journalists a history lesson. The thing they had to understand about Hong Kong, he said, was that before Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door Policy of the 1980s, Hong Kong was nothing but an insignificant producer of cheap trinkets, and before that, a mere fishing village. The genius of Deng’s policies, then, had made Hong Kong rich and great. The British contribution was barely worth mentioning.

Chu knew better of course. He knew that Chinese refugees from communism—including his own parents—had given Hong Kong a huge boost already in 1949. He also knew that Hong Kong’s wealth was largely made possible by the British Open Door Policy that goes back to the Opium War itself. The much-vaunted “rule of law” in Hong Kong was the result of British demands for extraterritorial rights. But Chu was giving his grateful interviewers the official, patriotic Beijing line. He was never directly elected to the legislature. He didn’t have to be. He is now an official patriot. History melts into myth in most countries, but few nations have been as systematic in rewriting history to match the politics of the day as China, and as oblivious to its contradictions. Each dynasty began with a revision of history. Britain is now being written out of Hong Kong’s history, except as the rapacious, drug-pushing, imperialist source of those “150 years of shame.”

Advertisement

In celebration of Hong Kong’s homecoming, the Chinese and Hong Kong people have been shown a movie, made at great expense, entitled The Opium War. So far, the film has not been a hit, perhaps because the propaganda is too crude. One of the British actors, named Bob Peck, who plays an opium trader of such eye-popping, silent movie-style wickedness that you wonder whether he is meant to be comic, complained in an interview that he was “unable to develop his character.” He had, perhaps, rather missed the point, which was this: British barbarians and corrupt, opium-addicted Chinese traders had brought shame and humiliation on the Chinese people, first by trading in opium, then by opening Chinese ports for business, and finally by taking Hong Kong. The British traders had introduced disorder in the Chinese cosmos; the Communist Party has finally restored it. In fact, however, opium was the spark that lit the fuse but not the main issue at stake in the Opium Wars. The clash was between Britain’s aggressive insistence on free trade and the Qing court’s equally vehement insistence on receiving tributes from foreigners instead of trading with them.

As often in patriotic myths, the sullied purity of the nation is symbolized by a beautiful young girl, who is ravished by the barbaric foreigner, in this case by Captain Elliot, the British trade representative in Canton during the 1840s. After a drunken lunge at the Chinese girl, his eyes blazing with bestial lust, he says: “Hong Kong, I want it!”

Hong Kong, we are to understand, is the raped Chinese innocent. Then, however, ruined by the barbaric embrace, she becomes the fallen woman, a Suzy Wong who would sell her own mother for a pot of gold. In the elaborately staged patriotic song and dance shows that were staged in Beijing as well as in Hong Kong, Hong Kong’s reputation was symbolized by dancers wearing dollar signs on their heads. But Western imperialist enclaves in China created pockets of freedom to do more than make money. Revolutions were hatched in cities like Canton, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. It was this, perhaps more than pornography, that Deng Xiaoping had in mind when he warned against the “foreign pollution” which came pouring through his own Open Door.

The patriotic symbol of China is of course not an Open Door at all but, quite the opposite, a Great Wall. In an enormous show staged at the Workers’ Stadium in Beijing—a show which would have done Leni Riefenstahl proud—thousands of young men, bellowing like a chorus of slaves, piled block upon block to form a massive Great Wall, protecting China from the barbarians. The homecoming of Hong Kong was also a celebration of the Great Wall, of Chinese xenophobia, of the Middle Kingdom’s revenge over past humiliations. It is understood that trade brings wealth, and wealth brings power. One Country, Two Systems is meant to preserve Hong Kong’s capacity to produce wealth. The closely guarded border separating Hong Kong from its motherland is supposed to shield Hong Kong from poverty and communism. But the “purity” of China must be protected as well. And so, for another fifty years, a wall will cloister the fallen woman, while she continues to rake in the cash.

2.

In their Empire, the British would award titles and medals to local worthies who had done their bit to maintain British rule. So also in Hong Kong. But in the week before the homecoming a new, Chinese award was announced: the Grand Bauhinia Medal, given to those who had “fostered among Hong Kong people a love for the motherland,” and who had “shown concern for and also identified with China’s accomplishments.” Sir S.Y. Chung, a former loyal servant of the British Empire, and T.S. Lo, another ex-supporter of British rule, were both awarded the GBM. Neither was ever a Communist, but that is beside the point. They now love China. It is not always clear what this means. Is China a culture, a state, a race, or all three? Chinese, like pre-war Germans, have an identity problem. All Chinese, whether they live in Hong Kong, Shanghai, or Vancouver, are supposed to love China. (The cheers in London’s Chinatown on June 30 appear to have rung louder than in Hong Kong—but then Gerrard Street won’t be ruled from Beijing.) Official patriotism, however, is easy to define: to love China is to love its rulers. Like the Yellow Emperors in the past, the Chinese Communist Party expects to be paid tribute by all patriotic Chinese. That is what the GBM is for.

Advertisement

Chinese patriotism is hard to resist, especially for Chinese living abroad, or under colonial rule. Racial pride can be the only form of satisfaction to people who lack political representation. Take the case of Mr. Lim Ken-han, the conductor of the “100% Chinese” Hong Kong China Philharmonic. He was furious that the Hong Kong Philharmonic, which contains musicians of various nationalities, was invited to play at the homecoming ceremonies, and not his own orchestra, which, he said, was “racially more suited.”

Lim is not a Communist, as far as I know. He was born in the Dutch East Indies, educated in Amsterdam, and went to live in China in 1952, to help rebuild the motherland. In the 1960s, Lim was arrested and tortured by Red Guards. His sin was to have claimed that Western composers were worth playing. For five years, he was forced to clean toilets. Before he escaped to the relative liberty of Hong Kong, Lim’s patriotism was rejected in the most horrible manner. Yet, here he is, in a rage because he can’t sufficiently express his love for China.

It was, you might think, particularly difficult for Hong Kong Chinese to resist official patriotism, for they had no other patrie. Very few ever identified with Britain. For an older generation of refugees, Hong Kong itself was a temporary shelter, not a home. The so-called native Taiwanese, whose ancestors left the Chinese mainland several hundred years ago, can turn their sense of grievance against the mainlanders, who came to Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek, into a sense of local nationalism. Attachment to the Taiwanese soil is their antidote to official Chinese patriotism. This was never an option for the Hong Kong Chinese. Now, for the first time, they have to define who they are, under Chinese sovereignty.

Before the homecoming ceremonies began, I attended a gathering of Hong Kong artists at a modern gallery. Most were in their twenties. “I feel Chinese,” said one young man, “just as Chinese as the people in China, but I don’t identify with a government whose ideas are derived from a nineteenth-century German intellectual.” Others stressed a vague Hong Kong “identity,” expressed through its commercial culture and its Cantonese pop songs. Others still refused to get pinned down to any collective identity, let alone a racial one; they were citizens of the world. But all agreed that they loved Hong Kong for its cosmopolitanism, its freedom, and its openness to foreign people and ideas—the very things, in short, which official patriotism so often seeks to contain behind walls.

There is, however, an alternative tradition to official Chinese patriotism. It is loosely termed the May 4th spirit. On May 4, 1919, students in Beijing demonstrated for a freer, stronger, more modern China. The movement, which spread to intellectuals and was backed by many businessmen and professionals, was emotional, often muddled, but undoubtedly patriotic. With its commitment to “democracy and science,” and under the influence of Marxism, feminism, and many other -isms, the May 4 Movement constituted a kind of counter-patriotism, set against the authoritarian rulers of Beijing. It was the May 4 spirit which the students invoked on Tienanmen Square seventy years later, and it is in the same spirit that political activists and intellectuals in Hong Kong today hope to build a democratic Hong Kong, and eventually a democratic China. That is why you often see the bust of Lu Xun, the most famous critic to emerge in the May 4 generation, standing on their desks.

When Martin Lee, the lawyer who heads the Hong Kong Democratic Party, spoke from the balcony of the Legislative Council on July 1, in the first rain-soaked hour of Chinese rule, he spoke as a patriot, and a democrat. He was proud that Hong Kong had become part of China again. But without freedom, he said, Hong Kong would soon lose its worth. And you cannot have freedom, he concluded, without democracy. Only a few thousand people had braved the weather to come out and listen, and many of them were foreign reporters, eager for a story to break the tedium of official ceremony. But numbers can deceive. Before the summer of 1989, Hong Kong people were said to be indifferent to politics. Before and after June 4, a million marched in the streets. As Martin Lee said, “Hong Kong has discovered her spirit.” To anyone who witnessed that spirit in 1989, the sight of dancers wearing dollar signs in mass parades was a degrading spectacle which did nothing to elevate the homecoming celebration.

President Jiang Zemin said that future Hong Kong governments would be freely and universally elected. He also said that they should never contain “anti-Chinese elements,” and that Hong Kong would always be “in the hands of patriots.” In this menacing definition of patriotism, Martin Lee is decidedly not a patriot. The democrats are marked as “anti-Chinese elements.” Before June 30, such elements were protected from Chinese rulers by colonial borders. In a way, this suited the rulers too: dangerous ideas were insulated. Now, for the first time since the 1920s and 1930s, two kinds of Chinese patriotism will clash under one Chinese flag: the authoritarian kind and Martin Lee’s kind, the May 4th kind. On the face of it, Lee and his fellow democrats don’t stand a chance. The official patriots have the money and the guns. But in the long run, the love of liberty might yet turn out to be stronger. In that happy event, Hong Kong’s homecoming will prove to have been the most dangerous tribute ever to fall into a Chinese tyrant’s lap.

—July 17, 1997

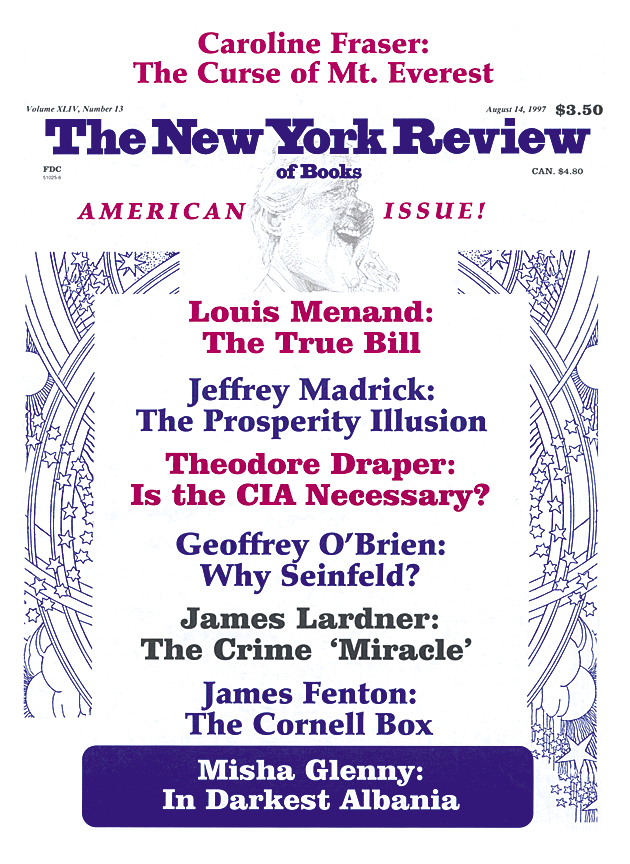

This Issue

August 14, 1997