1.

To unravel my first associations with Shakespeare is like trying to clamber back into the core of childhood. My parents worked in the theater—my mother as actress, my father as director and theater owner—and stages figured early on as places of magical transformation. Seeing the process from the wings did not make it any less magical: quite the contrary. The stage was a place where people became other than what they were, in a fully real alternate world. The most highly developed aspect of that other world was called Shakespeare, conceived not as an individual but as an inventory of places, costumes, roles, phrases, songs.

Countless artifacts served as windows into it: a book of cutout figures for a toy theater, based on stills from Olivier’s Hamlet; Classic Comics versions of Hamlet, Macbeth, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream; recordings of John Barrymore as Hamlet and Olivier as Henry V and (most memorably) an Old Vic Macbeth whose bubbling-cauldron sound effects and echo-chambered witches’ voices haunted me for years; splendidly melodramatic nineteenth-century engravings of Hamlet in pursuit of his father’s ghost, Romeo running Tybalt through, Caliban and the drunken sailors carousing on the beach; prints of Sarah Siddons and Edmund Kean in their most famous roles; a whole world of Victorian bric-a-brac and accretions out of Charles and Mary Lamb; Victor Mature as Doc Holliday in John Ford’s My Darling Clementine, reciting “To be or not to be” in a Dodge City saloon. There were productions, too, of which I remember none better than John Gielgud standing alone in modern dress on the stage of a school auditorium on Long Island enacting the abdication of Richard II; and there were Olivier’s three Shakespeare movies, the most recent of which, Richard III, had its American premiere on television in 1956.

It was a world that came into focus very gradually, little pieces clinging to memory out of a whole at first immense and vague. Probably the first details absorbed were of props and clothing—a crown, a dagger, a robe—augmented gradually by gestures, phrases, half-understood speeches. I can just about recall the uncanniness, on first encounter, of the exclamation “Angels and ministers of grace defend us!” Even more peculiar in their fascination were those words not understood at all: aroint, incarnadine, oxlips, roundel, palpable, promontory. No subsequent encounter with lyrical poetry ever exercised the initial hypnotic power of such a phrase as “Those are pearls that were his eyes.”

This Shakespeare existed outside of history, like Halloween or the circus. He was the supreme embodiment of the Other Time before cars or toasters, the time of thrones and spells and madrigals, imagined not as a dead past but as an ongoing parallel domain. So it was that I came to participate in a sort of religion of secular imagination: a charmed world whose key was to be found in the plays themselves, in all those passages where Shakespeare, through the mouth of Puck or Jaques or Hamlet or Prospero, appeared to give away the secret of a mystical theatricality, a show illusory even where it was most palpable.

The plays were just there, a species of climate: a net of interrelations extending into the world and generating an unforeseeable number of further interrelations. Why this should be so did not seem particularly important. Having managed to bypass the didactic initiation into Shakespeare favored in most schoolrooms—where every aesthetic pleasure must be justified in the name of some more or less hollow generality about will, or fate, or human relations—I didn’t need to look for reasons for the endless fascination. Certainly the sociology of the sixteenth century, or the development of the English theater, or the mechanisms of religious and political thought in early modern Europe seemed to have little to do with it. Any piece of writing, after all, came with such local meanings attached; every Elizabethan and Jacobean play was loaded to the brim with comparable social revelation. Something else had motivated a culture to adopt this vocabulary of situations, roles, and locations as the materials for its collective dreaming: something less susceptible to quantitative analysis than scope or invention. What but some mysterious generosity in the author could make possible such an infinitely flexible repertory for the theater of the mind?

If any era could call that flexibility into question it is a post-postmodern moment skeptical by now even about its own skepticism, and unable to refrain from an anxious cataloguing of inherited knowledge it can neither quite forget nor celebrate altogether without qualms. Shakespeare is the past, and the past is something we don’t know quite what to do with; we toy uncertainly with a millennial sense of impending drastic rupture, as if preparing to say goodbye to everything, even Shakespeare. With or without regrets: on one side there is the conviction (to quote from a notice posted recently at the MLA1 ) that “the current explosion of the uses of Shakespeare often consolidate elite and dominant culture” (the notice goes on to speak disparagingly of “Shakespeare’s status as high cultural capital”), on another the gloomy suggestion that in our present debased condition we are barely worthy of Shakespeare at all.

Advertisement

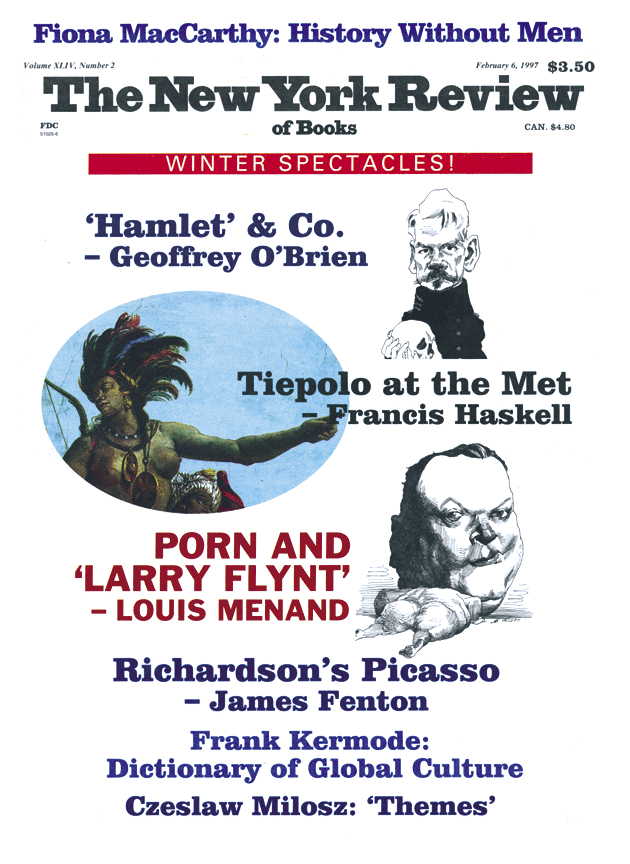

Nonetheless a sort of boom has been announced, and by virtue of being announced has gained official media recognition as a phenomenon; the Globe is at last reconstructed in South London (the culmination of a long and loving process which has involved among other things a rediscovery of Elizabethan construction techniques); new editions and CD-ROMs proliferate; a humorous compilation entitled Shakespeare’s Insults becomes a bestseller, with accompanying magnetic Wit Kit; and in the wake of last year’s films of Othello and Richard III we have been given in short order a Hamlet, a Twelfth Night, a sort-of Romeo and Juliet, some large chunks of Richard III interspersed in Al Pacino’s immensely entertaining filmic essay Looking for Richard, and a Midsummer Night’s Dream (directed by Adrian Noble) still to come. It isn’t exactly the Revival of Learning, and it is unlikely (although I would be glad to be told the contrary) that wide-screen versions of Measure for Measure, Coriolanus, or The Winter’s Tale will be coming any time soon to a theater near you, but it beats another movie about helicopters blowing up.

Doubtless there are thoroughly prosaic reasons for the momentary surge, having more to do with the random convergence of financing and marketing possibilities than with some cultural moment of reckoning. In a marketplace hungry for any pre-tested public domain property with instant name recognition, Shakespeare clearly has not altogether lost his clout, although his near-term bankability will certainly depend a great deal on the box office receipts of Kenneth Branagh’s textually uncompromising four-hour Hamlet. In the meantime singular opportunities have been created, not to recapitulate but to reinvent.

Reinvention has always been the function of Shakespeare in performance. It could have turned out otherwise: if the English Civil War had not disrupted the line of transmission, or if the post-Restoration theater had not rejected the plays except in heavily revised form, we might have something more in the nature of Kabuki or Peking opera, a fixed tradition of gestures and voicings, with ritual drumbeats and trumpet flourishes marking the exits and entrances. Of course there have always been productions—more a few decades back than now, perhaps—that inadvertently produced just that effect, of watching an ancient play in a foreign language as it moved through its foreordained paces.

In the face of such displays audiences often tended to shut down. A brilliant Shakespearean parody in the 1960 English revue Beyond the Fringe hilariously summed up everything that has ever made Shakespeare in performance more burden than delight: the mellifluous rote readings gliding incomprehensibly over gnarled syntax and thickets of argument, the versified rosters of the history plays sounding like nothing so much as medieval shopping lists (“Oh saucy Worcester!”), the bawdy uproariousness and farcical mugging designed to disguise the fact that even the actors didn’t get the jokes.

That parody, with its evocation of a lost era of complacent pageantry, came to mind while watching the recent production by Jonathan Miller (as it happens, one of the creators of Beyond the Fringe) of A Midsummer Night’s Dream at London’s Almeida Theatre. Here was the driest possible reimagining of a play capable of being smothered in ornate fancies: a Dream without fairies or fairy bowers, without even a hint of woodland magic or, indeed, of woodland. Miller recasts the play as a Thirties comedy of precise class distinctions, where the mortals—Theseus as lord of the manor, Hermia and Helena as bright debs pursued by young fashion plates of inspired fatuousness, Bottom and company as working men recruited from the local pub—are indistinguishable from Oberon as a somewhat tattered aristocrat, Titania as a sleek hostess out of a Noel Coward play, Puck and the other fairies as reluctant butlers inclined to be surly in their off-hours. Mendelssohnian echoes are displaced by “Underneath the Arches” and some snatches of ready-made dance music. In place of palatial pomp and natural wonderland, there is an unchanging set (designed by the animation specialists the Quay Brothers) consisting of rows of receding glass fronts, like an abandoned arcade, and permitting endless variations on the entrances and exits in which the play abounds.

Although some English critics felt that Miller had cut the heart out of the play by his policy of deliberate disenchantment, he seems rather to have demonstrated that the enchantment lies elsewhere than in light shows or acrobatics. Instead of magic, he gives us the accoutrements of Thirties drawing room comedy, appropriately enough in a retrospective culture for which Thirties comedy, whether Private Lives or Bringing Up Baby, serves as a gossamer substitute for more substantial magic. By a similar process of analogy, Shakespeare’s hierarchies of courtiers and mechanicals and nature-spirits are mimicked by the gently graduated hierarchies of the English class system in a later phase, the great chain of being linking landed gentry to their groundskeepers and socialites to their chauffeurs. The pastoral sublime of Dream is transmuted into the terms of a more recent version of pastoral, the weekend country-house party as imagined by P.G. Wodehouse or Agatha Christie.

Advertisement

The net effect is not to do violence to the play, but to give it another text to play against, a visual and behavioral text compounded of fragments of Thirties movies, plays, popular songs, magazine covers, a hundred tiny rituals and breaches of etiquette. It is a way of measuring distances: Shakespeare’s distance from the Athens of Theseus, the distance of the 1930s from the 1590s, and our distance from all of those times. To put Dream through this particular wringer—reimagining every line precisely as if someone else (W. Somerset Maugham? Terence Rattigan?) had written it, so that Theseus’ prettiest set pieces become exercises in obligatory speechmaking, and Oberon’s evocations of herbs and flowers are delivered with a cosmopolite’s distaste for mucking about outdoors—turns out to be a way of forcing out some of its bitterer aftertastes.

The celebration already anticipates the incipient hangover; as soon as the play ends, Theseus and Hippolyta will settle into a loveless marriage, and the young lovers will begin to realize that their lives will not improve on the mysteries of the vision they have just woken from. The hilarity of a good feast, with Pyramus and Thisby for entertainment, may in fact be as good as it is ever going to get. The play needs only itself to confirm that the magic is real; the production adds the somewhat waspish acknowledgment that it is also unattainable outside the theatrical moment.

“Shakespeare, more than anyone else,” writes Miller of this production, “recognized that the stage is a place in which blatant pretense is a perfectly satisfactory alternative to miraculous illusion.” By eliminating decoration, by favoring the matter-of-fact social function of the language over its poetry, Miller lets us see Dream in skeletal form. Nothing essential is lost because the play turns out not to be about fairies any more than it is about weekend country-house parties in the 1930s. If it is about anything it is about the music of thought, which is why William Hazlitt considered the play intrinsically unstageable. Indeed, it may well have been unstageable in 1816 when, at Covent Garden, Hazlitt saw it “converted from a delightful fiction into a dull pantomime…. Fairies are not incredible, but fairies six feet high are so.”2 Perhaps—and wouldn’t it be odd if it were so—the art of performing these plays to their fullest advantage is only now being invented.

But where, and for how many, they will be performed remains a question. It is a long way from the familial intimacy of the Almeida—with its audience and actors exquisitely attuned to each other, and a seating capacity one tenth of Shakespeare’s own playhouse (300 against the Globe’s 3,000)—to the wider and colder world of multiplexes and cable television and the megastores in which the shiny video boxes containing Hamlet and Twelfth Night will have to compete on equal terms with Mars Attacks! and Beavis and Butt-head Do America. It’s a world that’s hard on old material, even as it pays lip service to what is “vintage” or “immortal”; where the earlier Shakespeare films are apt to turn up under rubrics such as Nostalgia or Classic Hollywood, and a phrase like “timeless classic” is just as likely to be applied to Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy as to Henry V.

Shakespeare movies have never exactly been a genre in the same sense as cowboy pictures or musicals. There have never been enough of them, for one thing; although the record books cite astonishing numbers of adaptations, most turn out to have been made in the silent era. As for the filmmakers who have seriously explored the stylistic possibilities of Shakespeare adaptations, the list is very small: Olivier, Welles, Kurosawa, Polanski, and a few others. In any event it’s something of a genre apart; there are regular movies, and then there are Shakespeare movies.

Kenneth Branagh, who kicked off this particular cycle of Shakespearean revival with his 1989 Henry V, challenged the distinction. With a defiance worthy of the victor of Agincourt he demonstrated that Laurence Oliver’s Shakespeare films of the Forties and Fifties, and the performance style they embodied, could no longer be regarded as definitive. He also undertook to make a genuinely popular movie, against odds stiffer than those Olivier faced, at a moment when more than ever before Shakespearean language had to fight for a hearing. Henry V played at the local multiplex alongside Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and it was obvious that Branagh was prepared to meet that competition on its own ground.

Yet for all its superficial indications of pop refurbishing—Derek Jacobi’s playing the Chorus in modern dress and wandering among the trappings of a movie studio, or Branagh’s Henry striding, to the accompaniment of strident electronic wheezing, into a medieval council chamber framed to look as much as possible like the inner precincts of Star Wars’ Darth Vader—the new Henry V gave signs of an almost purist agenda. To a degree unusual in Shakespeare movies, one had the impression of having actually sat through a production of the play. Branagh restored many scenes—Henry’s entrapment of the traitorous English lords, his threats of massacre at Harfleur, the hanging of his old companion Bardolph—that would have detracted from Olivier’s single-minded depiction of heroic national effort (although even Branagh could not bring himself to include the English king’s injunction to “cut the throats of those we have”).

What was most strikingly different was the level of intimacy at which Branagh’s film was pitched. The Olivier version of 1944 clearly occupied a niche quite separate from the other films of its moment, delivering in clarion tones a classical language inspiring but remote. For Branagh this was no longer an available choice. The continued power of Henry V was not to be taken for granted; what for Olivier had been a universally recognized (if far from universally enjoyed) cultural monument now had to defend itself.

The chief point of Branagh’s direction was to keep the language in front of the audience at all times, with Derek Jacobi’s clipped, almost haranguing delivery leading the way. The job of the actor was to clarify, line by line and word by word, not just the general purport of what the character was feeling, but the exact function of every remark, as if some kind of match were being scored. Abrupt changes of vocal register, startling grimaces and seductive smiles, every actorly device served to maintain awareness that absolutely every moment had its singular thrust, and thereby to keep the audience from being lulled into an iambic doze. The result was a more pointed, even jabbing style, a tendency to deflate sonority in favor of exact meaning, while at the same time giving the meter of the verse a musician’s respect, and the rhetorical substructure a lawyer’s questioning eye.

As I first listened, in that same multiplex, to the accents of Henry V—“But pardon, gentles all,/The flat unraisèd spirits that hath dared/On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth/ So great an object”—transmitted in Dolby Stereo, an unanticipated excitement took hold. It didn’t matter that I could read those words any time, or pop a video of the Olivier film into the VCR. The thrill was to hear them in the multiplex, in that public space from which the possibility of such language had been essentially barred. Here was real home-cooked bread, water from the source. It was possible to imagine that the strangers around me shared a similar unarticulated longing for a strain of expression that the culture seemed programmed to withhold.

2.

Everyone who subscribes to cable television has had the experience of switching rapidly from channel to channel and hearing at every stop the same tones and inflections, the same vocabulary, the same messages: a language flattened and reduced to a shifting but never very large repertoire of catchphrases and slogans, a language into which advertisers have so successfully insinuated their strategies that the consumers themselves turn into walking commercials. It is a dialect of dead ends and perpetual arbitrary switch-overs, intended always to sell but more fundamentally to fill time: a necessary substitute for dead air. Whether in movies or television dramas, talk shows or political speeches or “infotainment” specials hawking hair dyes and exercise machines, the homogenization of speech, the exclusion of anything resembling figurative language or rhetorical complexity or any remotely extravagant eloquence or wordplay or (it goes without saying) historical or literary allusions of any kind whatever, becomes so self-evident that the only defense is that winking tone of faux inanity of which the ineffable “whatever” seems to be an ironic acknowledgment. By contrast the dialogue in the old Hollywood movies unreeling randomly night and day—The Road to Rio or The Falcon in San Francisco or The File on Thelma Jordan—seems already to partake of some quite vanished classical age: how soon before it, too, needs footnotes?

Nothing leads from or to anything; the show rolls on because it isn’t time for the next show yet. It is talk without any but the most short-term memory, as if language were not to be permitted its own past, a state of affairs which makes language in some sense impossible. In this context Shakespeare assumes an ever-stranger role as he becomes the voice of a past increasingly less accessible and less tractable, the ghost at the fast-food feast. If in translation Shakespeare can remain our contemporary, in English he carries his language with him, a language by now almost accusatory in its richness when compared with the weirdly rootless and impoverished speech of Medialand. “I learn immediately from any speaker,” wrote Emerson, “how much he has already lived, through the poverty or the splendor of his speech.”3 But there is no telling what a four-hundred-year-old man will be saying; the older he gets, the more it changes, and we no longer know if we really want to hear everything. It is like peering into a flowerpot full of twisted vines and splotched discolored lichen surviving improbably from some ancient plot.

It is absurd that Shakespeare alone should have to bear this burden, as if the whole of the European past rested in him alone, but that’s only because nearly everyone else has already been consigned to the oblivion of the archives. We aren’t likely to get (speaking only of the English tradition) the Geoffrey Chaucer movie, the Edmund Spenser movie, the John Webster movie, the John Milton movie, the William Congreve movie, the Laurence Sterne movie, or even the Herman Melville movie; and the Bible movies, when they appear, owe more these days to the cadences of Xena: Warrior Princess than to those of King James. (One of Orson Welles’s last and most quixotic film projects was a movie of Moby-Dick consisting of himself, in close-up, reading the novel against an empty blue background.) Shakespeare has to stand, all by himself, for centuries of expressive language erased by common consent from the audiovisual universe which is our theater and library and public square.

If Shakespeare movies are to be worth making at all, they can hardly duck the language. It isn’t simply that the language cannot be handled gingerly or parceled out in acceptably telegraphic excerpts; the words must be entered, explored, reveled in. Syntax must be part of screen space. (The new sensitivity of recording technology, with its potential for communicating an awareness of depth and distance, serves admirably toward that end.) How refreshing it proves occasionally to reverse the primacy (not to say tyranny) of the visual, that fundamental tenet of filmmaking textbooks.

Disregard this problem of language and the upshot can be something like Baz Luhrmann’s high-speed, high-concept William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. There is no real reason why Luhrmann’s updating could not have worked; the whole mix, complete with automatic weapons, hip-hop cadences, religious kitsch, and teen sex, could have added up to the kaleidoscopic excitement obviously intended. As it is, the compulsive cleverness of the postmodernization—Friar Lawrence sending his message to Romeo by Federal Express, members of the Capulet and Montague gangs sporting CAP and MON license plates—keeps undercutting the teen pathos to the point of parodying it. However amusing Luhrmann’s conceits of characterization (Lady Capulet as blowsy Lana Turner wannabe, Mercutio as drag queen), they seem to have strayed in from his more charming debut feature Strictly Ballroom.

It’s the skittish handling of the language, though, that reduces Luhrmann’s film to little more than a stunt. While he gets a bit of mileage from the accidental intersections of Elizabethan with contemporary usage (as when his gang members call each other “coz” and “man”), any speech longer than a few lines just gets in the way, and the effect all too often is of sitting in on the tryouts at a high school drama club. The Shakespearean text begins to seem like an embarrassment that everybody is trying to avoid facing up to; Luhrmann would have been better off dropping the dialogue altogether and hiring Quentin Tarantino to do a fresh job. There are many ways to get Shakespeare’s language across, but trying to slip it past the audience as if it might pass for something else isn’t one of them.

Of course it’s possible to think of Shakespeare outside of language altogether (especially if you’re Russian or Japanese): as inventor (or repackager) of endlessly serviceable fables, a choreographer of bodies on a stage, a visual storyteller whose most celebrated moments (Hamlet leaping into Ophelia’s grave, Macbeth confronting Banquo’s ghost at the feast) can be reduced to dumb show. It would be perfectly possible to stage the plays in pantomime without losing their structural force. This is the Shakespeare who is the inexhaustible font of ballets and engravings, musicals and comic books.

A remark by Grigori Kozintsev, the director of Russian versions of Hamlet and King Lear, pretty well sums up the orthodox “cinematic” view on filming Shakespeare:

The problem is not one of finding means to speak the verse in front of the camera, in realistic circumstances ranging from long-shot to close-up. The aural has to be made visual. The poetic texture has itself to be transformed into a visual poetry, into the dynamic organisation of film imagery.4

This is an unexceptionable precept for a director working in a language other than English, and one need only turn to Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood or Ran, or Aki Kaurismäki’s Hamlet Goes Business (filmed on location in a succession of unbelievably sterile Helsinki office suites), to see it put sublimely into practice. But when a Shakespeare film is made in the English language, the unavoidable problem is precisely one of finding means to speak the verse in front of the camera. No way to sidestep the embarrassment of poetry, even if it is a term by now so fraught with difficulties that some contemporary academics in their discussions of Shakespeare prefer to enclose it in quotes, an awkward relic of superannuated discourse.

The Kozintsev doctrine has been carried through by one English-language director, of course. The Shakespeare films of Orson Welles triumph over the sheer inaudibility of much of their dialogue through an idiosyncratic vocabulary of spaces and masks. Othello is more like a symphonic poem inspired by the play than the play itself: but what a poem. Welles proceeds by analogies. Shakespeare’s language is like the waves dashing against the walls, is like the cage in which Iago is hauled laboriously to the ramparts, is like the glimmers and shadows with which the frame is irrigated. Even the few brief surviving scenes of Welles’s unfinished TV film of The Merchant of Venice (shown in Vassili Silovic’s documentary Orson Welles: The One-Man Band) instantly create a distinct universe, as Shylock, making his way into the Venetian night, is hounded by silent ominous bands of white-masked revelers, a commedia dell’arte lynch mob.

The long-deferred restoration of the currently unseeable Chimes at Midnight—a film whose visual splendor is matched only by the inadequacy of its soundtrack—will I am sure confirm it as the best (and most freely adapted) of Welles’s Shakespeare films. When it came out in the late Sixties, its elegiac note was drowned out by the more belligerent noises of the moment. Welles described it as a lament for the death of Merrie England—“a season of innocence, a dew-bright morning of the world”5—as personified by Falstaff, but it could as easily be seen as a lament for Welles, for the kind of movies he wanted to make and no longer could, and beyond that for Shakespeare as he receded however gradually into an unknowable past.

In lieu of lament, Al Pacino’s Looking for Richard proffers jokes and exhortations, backtalk and man-on-the-street interviews and off-the-cuff commentaries. Pacino intervenes in his own partial production of Richard III to question and elaborate, almost in the same way a puzzled member of the audience might be tempted to: What’s going on? Who is this Margaret? The Richard III scenes themselves—including some very strong work by Kevin Spacey, Winona Ryder, and others—are so freshly conceived that it seems a pity not to have done the whole play; Pacino looks as if he could give us yet another kind of Shakespeare movie. His Richard is far scarier than Olivier’s or the somewhat campy Mosleyite portrayed by Ian McKellen in Richard Loncraine’s recent film version, a real killer especially when he’s suffering verbal assaults in silence. It’s all the more jarring to revert to the present and the jovial sparring of actors among actors; but that back-and-forth movement makes this one of the best movies about the acting life. Actors here are the true scholars, the ones who mediate between the text and the world, a secret order of preservationists keeping alive what elsewhere is only mummified. We are left with the implication that the players know things the scholars have forgotten, and that they are joyful in that knowledge.

It is not precisely joyfulness, and certainly nothing like glee, that is exuded by Trevor Nunn’s melancholic adaptation of Twelfth Night; or if so it is a joy sufficiently muted to accord with prevailing moods that range from Chekhovian-autumnal to Beckettian-wintry. The tone is set by Ben Kingsley’s Feste, conceived rather scarily as a prophetic beggar lurking in the background and seeing all, a figure whose intimations of latent violence and mad wisdom suggest that Lear’s fool has been grafted onto Olivia’s. The revels of Sir Toby and Sir Andrew are played with excellent flair while at the same time evoking a down-beat Last Tango in Illyria. At every turn we are given to see how the comedy is about to slip into the realm of the tragedies, the shipwreck into that of Pericles, the duel into that of Hamlet, the wronged Malvolio into a figure of vengeance capable of destroying the whole household.

That said, Nunn’s film succeeds beautifully in its chosen course. It is for the most part superbly played, although Helena Bonham Carter is somewhat lacking in the haughty disdainfulness required of Olivia; her surrender to love isn’t enough of a humiliation, and so fails to echo the far harsher humiliation of her steward. Imogen Stubbs by contrast is a tough and wary Viola who keeps the film focused on the real risks and terrors of someone cast up in hostile territory. The sadistic tormenting of Malvolio, always the trickiest passage to negotiate, is here allowed to play itself out into the exhaustion, moral and physical, of the tormentors. When one sees Twelfth Night back-to-back with Hamlet (as it may well have been written), it is hard not to think of the plays as mirror images, a comedy that just barely avoids being tragedy and a tragedy that tries against all odds to be a comedy.

This Twelfth Night, like Branagh’s Hamlet, is set in a mythical nineteenth century which seems to stand vaguely for the whole European past, as if that were as far back as we could go without suffering hopeless disorientation. Despite the clothes and the furniture, neither film has a particular nineteenth-century feel; it’s more a question of meeting the seventeenth century halfway, settling on a space which is neither quite our own world nor quite Shakespeare’s, inventing a historical era which—like the period in which cowboy movies take place—never quite happened. We want urgently to step outside of history but have perhaps forgotten how.

Finally—speaking of risks—there is Branagh’s Hamlet, a movie on which he appears to have gambled his whole career. If this one doesn’t fly, who knows when we shall see another of his Shakespeare films? On the one hand, the film pertains to the universe of high-concept marketing: a 70-millimeter epic (the first such in Britain for twenty-five years) with sumptuous sets, an all-star cast with cameo appearances in the manner of Around the World in 80 Days (Jack Lemmon, Robin Williams, Billy Crystal, and Charlton Heston, not to mention the Duke of Marlborough, all assume minor roles), and a four-hour running time complete with an intermission to bring back memories of the early-Sixties heyday of blockbuster filmmaking, the days of Spartacus and Lawrence of Arabia.

Branagh has another concern, however: his desire to respect against all odds the integrity of Shakespeare’s text, and this puts his movie paradoxically closer to such resolutely marginal projects as Eric Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois (1978), in which Chrétien de Troyes’s twelfth-century courtly romance is recited to the accompaniment of quasi-medieval stage effects, and Jacques Rivette’s Jeanne la Pucelle (1994), which in recounting the career of Joan of Arc restricts itself to the language of the earliest chronicles. (Branagh’s version actually is completer than complete, since it conflates the First Folio text with the extensive passages that appear only in the Second Quarto, thus producing something longer than any known version of the play.) The word—or more precisely Shakespeare’s words—is the life of this film, to which everything else, Blenheim Palace, Billy Crystal, FX, SurroundSound, is incidental.

The result might be pedantic except that Branagh isn’t a pedant, although his passion has its pedagogical side. In order to resolve the contradictions of his approach he has to resort to a kind of aesthetic violence which can easily be misread as vulgarization: the horror-movie visuals (the blade piercing Claudius’s head, the ground splitting open), the sometimes schmaltzy musical underscoring. The resort to such tactics has rather the effect of restoring a necessary vulgarity which other films have tended to polish. As in his previous adaptations but even more deliberately, Branagh undertakes to clarify the literal meaning by any means necessary. The silent movies he has concocted featuring the career of Fortinbras and the death of Priam function as footnotes, supplying a visualization which in a stage production would be left to the audience. This is the first Hamlet in which Old Norway (not to mention Hecuba, Priam, and Yorick) actually figures as a participant.

Branagh’s decision to present the play uncut was a brilliant one, however one may differ with one detail or another of his execution. The differences are of more than scholarly concern; the narrative rhythm is transformed, and Hamlet himself, while no less central, concedes a good deal more ground to those around him. The sententious digressions, contests of wit, and theatrical recitations—the repetitions, the circuitous approaches toward a point of negotiation, the interruptions and side chatter and discussions of urgent diplomatic affairs—these are what give the flavor of the milieu, without which Hamlet appears to take place in an abstract void. The full Hamlet has a different specific gravity, a density which makes it seem like the first great English novel, a Renaissance novel like such roughly contemporaneous Spanish works as the Celestina of Fernando de Rojas or the Dorotea of Lope de Vega, unplayably long narratives in dialogue form, interspersed at times with songs and poems. It works with time in a more expansive and open-ended way, sharing the ceaseless discursiveness and purposeful sprawl of Rabelais or Montaigne.

With all the rests restored, it becomes possible to look beyond the intrusive shocks of the plot and get a feeling for the life they have interrupted. In general, modern productions, and most especially modern film productions, cut to the plot line, as if the rest of it were bothersome persiflage. We pare Shakespearedown to streamline him, bring out “meanings” that we have planted there. Driven by an obsession to bring things into sharp focus, we simplify. Hamlet is a much more interesting and surprising work—and, with its roundabout strategies and gradual buildups and contradictions of tone, a more realistic one—when all of it is allowed to be heard, and it is bold of Branagh to have gambled on this more ambitious dramatic arc.

Olivier’s Hamlet, steeped in that marriage of Romanticism and Freud which is film noir, threads a lone path among expressionistic shadows and wreaths of mists before returning to confront the Others. In Branagh’s interpretation, Hamlet is one among a crowd of powerfully differentiated figures who play against each other as much as against him. He is a disturbing element in the midst of a very busy and brightly lit Renaissance court. Even “To be or not to be” is staged here as a two-character scene (or, more exactly, a three-character scene): while Branagh faces himself in a mirror (it is the mirror-image who is seen speaking), we see him also from the viewpoint of the hidden Claudius. This is a Hamlet in which Rosencrantz and Guildenstern function for once as central characters. The convergence of that pair and Polonius with the simultaneous arrival of the players and the recitation of the Hecuba speech (superbly done by Charlton Heston’s Player King, with just enough restrained hokum to identify him as an actor) is allowed all its complexity.

Branagh can be forgiven every failed touch—even the 360-degree pans (presumably intended to prevent visual stasis) which sometimes make it look as if the inhabitants of Elsinore are all on rollerblades, even Hamlet’s absurd final swing from the chandelier into the lap of the dying Claudius—for having maintained an essential lightness, the verbal quicksilver at the heart of it. For all the sometimes athletic action, this Hamlet is strung on its language. The words are the play, unfolding in a space open enough to give scope to its unruly energies.

This Issue

February 6, 1997

-

1

The notice requested submissions for an anthology to be titled Shakespeare Without Class: Dissidence, Intervention, Countertradition, edited by Bryan Reynolds and Don Hedrick. ↩

-

2

William Hazlitt, Characters of Shakespeare’s Plays (Chelsea House, 1983), p. 95. ↩

-

3

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The American Scholar,” in Essays and Lectures (Library of America, 1983), p. 62. ↩

-

4

Quoted in Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television, edited by Anthony Davies and Stanley Wells (Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 56. ↩

-

5

Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This Is Orson Welles, (HarperCollins, 1992), p. 100. ↩