1.

In the fragmented and seemingly directionless world of late-twentieth-century architecture, no concept beguiles the popular imagination more than that of “organic” design. The belief that all aspects of a comprehensive architectural scheme—from its landscape setting and the building itself to interior decoration—should be orchestrated as a seamless whole under the direction of one designer is the most enduring legacy from the last fin-de-siècle to our own. The longing for complete integration in architecture, from the broadest concepts down to the smallest details, with each reinforcing the other, explains much about the present-day fascination with the turn-of-the-century figures who brought the ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk to the building art more fully than ever before. Theirs was no mere personal expression, but part of a widespread reaction against the new social divisions brought about by the Industrial Revolution.

Three great proponents of that all-inclusive approach still claim a vast audience commanded by no living architect. In this country, Frank Lloyd Wright is the supreme example, his adherents and the publications about him increasing as his posthumous stature grows and his incomparable meldings of site and structure age gracefully. In Catalonia, Antoni Gaudí is virtually a national saint, with public responses to his idiosyncratic landmarks providing a litmus test for a host of political, religious, and cultural attitudes. And in his native Glasgow, a once-mighty trading center now with few economic resources save cultural tourism, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) has become the basis of a lucrative local industry and a worldwide cult.

It is not difficult to understand the particular appeal of Mackintosh’s work. Extreme and striking, his most famous designs—the high-backed chairs with which he furnished the dozen remarkable Glasgow tea rooms he executed for Kate Cranston between 1896 and 1917—are quite unlike any other chairs made before or since. Flagrantly exaggerated and patently impractical not only by the standards of the then-nascent Modern movement but also by those of the waning Victorian era, the chairs of Mackintosh nonetheless dramatize the act of sitting with greater authority than any of the more “functional” designs later produced by Marcel Breuer, Le Corbusier, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Indeed, the true function of a Mackintosh chair was to look arresting in a specific architectural setting, and at that his designs succeeded spectacularly well.

Even by themselves Mackintosh’s chairs retain a strong hieratic presence. One of the more memorable photographs of Prince Charles and Princess Diana during their protracted public displays of marital discord showed them slumped away from each other in reproductions of Mackintosh’s Argyle Street Tea Room chairs of 1898-1899. Though the scowls and body language of the unhappy couple suggested the contrary, the stately tall backs of the chairs, surmounted by oval motifs recalling the mon crests of Japanese nobility, invested the scene with an inviolably regal presence.

Almost seventy years after his death, Mackintosh is particularly revered in Japan, whose classical art and architecture had as deep an effect on his work as it did on that of his London-based contemporaries Aubrey Beardsley, E.W. Godwin, and James A. Whistler. Japan has been by turns xenophobic, adept at absorbing foreign influences, and worshipful of Japanesque tendencies in Western design. One of the most amusing manifestations of the latter is a 1993 Japanese comic-book biography of the Scottish architect, part of a series called Geniuses Without Glory. Several panels from it are reproduced in Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the superb catalog of the eponymous retrospective that began in Glasgow last year and is now on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “This is the original form of modern art, several decades ahead of its time,” declares one of the Japanese cartoon captions. “When we look at it, it has been so perfected that we don’t feel any strangeness.”

Perhaps it is asking too much that comic books reflect the latest in scholarly research when even one of the new publications on the architect—Charlotte and Peter Fiell’s handsomely illustrated but textually anachronistic Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868- 1928)—clings to the same myths and misapprehensions about his life and work that have persisted for more than four decades. The source of the Fiells’ standard interpretation of their subject as a tragically misunderstood innovator who was ultimately destroyed by a philistine society is Thomas Howarth’s pathbreaking Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Modern Movement,1 long the essential study.

Howarth’s life-and-works is one of those paradoxical scholarly efforts that in hindsight inspires mixed emotions. Howarth began his research in 1940 (itself an act of high optimism as the Blitz began), not long before the last survivors among the architect’s closest collaborators and patrons passed from the scene and only a dozen years after Mackintosh himself had died. Yet for all its value as a collection of primary source material and the catalyst behind a major reassessment of Mackintosh’s reputation, the book also perpetuated a number of misconceptions that only now have been corrected in the new catalog.

Advertisement

No historical writing is free from the biases of the times that produce it. Thus Howarth’s Mackintosh, first published in 1952, at the height of the International Style’s influence, fully reflects the then-prevalent attitude that the only significant nineteenth- and twentieth-century architecture and design was that which led to the triumph of reductive mainstream modernism. The oxymoronic proposition that a work of art can be “ahead of its time” (echoed in the Japanese Mackintosh comic-strip caption), when the very existence of an artifact proves that it is incontestably of its own time, permeates Howarth’s case for Mackintosh above all as a forerunner of modernism.

In that respect Howarth followed the lead established by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner in 1936 with his highly influential Pioneers of the Modern Movement: From William Morris to Walter Gropius,2 which included the first significant posthumous discussion of Mackintosh in a book. Typically, Pevsner would cite only those examples of architecture and design that supported his preference for minimalist aesthetics, only one of a much wider range of innovative tendencies in the period under discussion. Pevsner praised Mackintosh’s School of Art in Glasgow, which opened in 1899, because it “leads on to the twentieth century.” However, though he perceived that the School of Art’s “transparency of pure space will be found in all Mackintosh’s principal works,” he decried its expressionistic aspects, which influenced later European design trends that “held up the progress of the mainstream of modern architecture.”

To be sure, there are components of Mackintosh’s architecture, and especially his interior designs, that still seem quite contemporary to those raised during the heyday of High Modernism. The monolithic massing of his buildings (inspired by the severe elevations of Scottish baronial castles), the strong profiles of his furniture (often encased in a carapace of paint to emphasize surface over material), and the monochromatic palette of his room schemes (a striking departure after the riot of color, pattern, and texture characteristic of Victorian interiors) all purportedly pointed, in the interpretations of Howarth, Pevsner, Siegfried Giedion, and other midcentury polemicists, to the Platonic purity of the International Style.

In fact, many of the “signature” elements in Mackintosh’s work during the most creative decade of his career, from 1896 to 1906, can be found in the work of many of his contemporaries as well. Mackintosh’s very few domestic designs owe a clear debt to the houses of C.F.A. Voysey, the English Arts and Crafts architect whose updated Tudoresque cottages, stripped of quaint details and clad in whitewashed pebbledash (a stucco-like mortar aggregate mixed with small stones to create a rough texture), are more skillfully organized than Mackintosh’s residences, which are notably repetitive in floor plan. And Voysey’s variations on his primary theme of the upper-middle-class country retreat are more inventive than Mackintosh’s.

The furniture designs of the Vienna Secession, and specifically those of such members of the Wiener Werkstätte as Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, had a decisive effect on Mackintosh’s move away from the sinuous lines of Art Nouveau and toward the geometric and grid motifs of his Austrian counterparts. That change can be dated precisely to Mackintosh’s visit to Vienna in 1900, where his Scottish Room installation was shown at the Eighth Secessionist Exhibition.

Even white-walled rooms were not unheard of before Mackintosh and his wife (and frequent collaborator), the artist and designer Margaret Macdonald, transformed their first Glasgow flat as newlyweds in 1900 into an environment that one contemporary visitor recorded as being “amazingly white and clean-looking. Walls, ceiling and furniture have all the virginal beauty of white satin.”

Yet a decade earlier, Standen, the great Arts and Crafts country house in Sussex designed by Philip Webb and decorated by Morris & Co., had large expanses of white-painted walls in its principal rooms, and not merely in the utilitarian spaces where whitewash or distemper were used instead of more costly colored pigments. And even the New York apartment done up in 1898 by Elsie de Wolfe (one of the first professional woman decorators), for herself and her companion Elisabeth Marbury, had the white walls that by the end of the century were becoming a fashionable alternative to subfusc Victorian interiors.

Perhaps one of the clearest signs of Mackintosh’s secure place in the history of design is the fact that the superlative exhibition catalog edited by Wendy Kaplan, former chief curator of the Wolfsonian Museum in Miami Beach, makes no excessive claims for the subject’s solitary stature. The long-dominant portrait of Mackintosh—sketched by Pevsner, executed at full length by Howarth, and reduced to the cartoonish outline of the Geniuses Without Glory comic-book version—was that of the lonely, misunderstood rebel who flourished only briefly before being brought low by uncaring, uncomprehending philistines. Architecture is an art form with no one comparable to Vincent Van Gogh—the sobriety needed to win building commissions guards against erratic behavior—but the Romantic stereotype of the tortured creative genius dies hard and became an important article of faith in the Mackintosh cult.

Advertisement

One of the most remarkable aspects of the exhibition catalog is that while it does away with received ideas about his life and career, Mackintosh emerges from the demythologizing as an enormously sympathetic figure all the same. Of particular value are the three essays in the book’s opening section, “Mackintosh in Context.” In “Mackintosh and the City,” Juliet Kinchin, a lecturer at the Glasgow School of Art, provides a brilliant analysis of the economic and social conditions that made late-nineteenth-century Glasgow especially open to design innovation. As she writes:

It can be argued that the tangible form of [Mackintosh’s] architecture and design expressed a distinctive civic consciousness and a sense of cosmopolitan regional identity, while also reflecting the many conflicts and tensions that living in Glasgow entailed. On the one hand, Mackintosh’s stylistic assurance and theatrical panache seem in tune with the buoyancy of the city’s economy, its internationalism, and its climate of thrusting, competitive individualism. On the other, his work’s excessive tension and exaggeration point to an ideology under threat and to the disruptive potential of the prevailing social, economic, and technological forces. Similar creative tensions characterised other great manufacturing centres where the “New Art” (also known as Art Nouveau and National Romanticism) flourished—cities like Turin, Italy; Nancy, France; Chicago; and Brussels.

(And, she might have added, Barcelona.)

Heretofore most commentary on Mackintosh’s Glasgow has focused on the obvious contrast between his rarefied design schemes and the gritty industrial center that at the time was the second city of the British Empire. Yet Ms. Kinchin proposes that the city already had a century-long history of what might be called competitive decorating, which put a high premium on originality and startling effects. An artist of Mackintosh’s eccentric individuality was therefore able to succeed in Glasgow to an extent that would have been far more difficult in tradition-bound communities. Her essay, one of the most valuable contributions to the exhibition catalog, is an excellent example of the recent tendency for such publications (especially those of architecture shows) to include a chapter on the subject’s local setting and the larger forces that inevitably shape the forms that buildings and cities take.

Reinforcing Ms. Kinchin’s cultural interpretation is the informative chapter by Daniel Robbins, curator of British art and design at the Glasgow Museums, on the Glasgow School of Art. That progressive institution was supported with enlightened self-interest by the city’s industrial leaders to provide them with local talent for their burgeoning technical and manufacturing capacities. The Glasgow School of Art (whose new building would eventually become the crowning achievement of Mackintosh’s thwarted career) allowed its most famous pupil, the son of a police inspector, to receive a first-rate architectural and design education and to be launched, by the late 1880s, into the professional class. The school’s idealistic director, Francis Herbert (“Fra”) Newbery, was one of Mackintosh’s strongest advocates, and the story of his educational leadership and architectural patronage is well told in Mackintosh’s Masterwork: Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow School of Art, a richly illustrated book originally published in 1989 and now available in a paperback edition.

2.

Not the least of the opportunities the Glasgow School of Art afforded Mackintosh was the ability to meet the talented young women who made up a significant portion of the institution’s enrollment at a time when co-education, while rare in other disciplines, was increasingly common in the applied arts. It was at the school that he and his best friend and fellow student, Herbert McNair, met two independently well-to-do sisters, Margaret and Frances Macdonald, whose private incomes allowed them to enroll as day students, while the men, of more modest backgrounds, worked as architectural draftsmen by day to pay for their classes at night. Charles and Margaret, Herbert and Frances paired off, both couples sharing a romantic vision of a new kind of art and design that could elevate mankind to a higher spiritual plane. They soon became known as the Four, an inseparable unit that formed a movement of its own within the Glasgow School.

The third of the exhibition catalog’s “Mackintosh in Context” essays, Janice Helland’s “Collaboration Among the Four,” is an admirable achievement that parallels several other recent re-evaluations of the parts that lesser-known female colleagues had in work long solely ascribed to some of this century’s most celebrated male architects. Pat Kirkham’s Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century3 attributed a far greater share in that couple’s collaborations than had been done before to the self-effacing Mrs. Eames, and Matilda McQuaid’s 1996 Museum of Modern Art exhibition and catalog on the work of Lilly Reich gave Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s principal personal and professional partner much-deserved credit for her central part in his career. So does this persuasive chapter emphasize how inextricably bound up Mackintosh’s designs—and fortunes—were with those of Macdonald.

It should not have taken this long—Mackintosh died in 1928, Macdonald five years afterward—for the record to be set straight. He sometimes signed works with both sets of their initials (though some scholars debate whether this meant actual collaboration, conceptual inspiration, or merely, in the case of his series of botanical watercolors of circa 1915, her proximity when they were executed). Margaret Macdonald often provided the decorative insets that imparted such a distinctive air to Mackintosh’s interiors and furniture. Her beaten-metal mountings of wraithlike female figures (symbolism that earned the Four the epithet of the Spook School) gave his cabinetry the preciousness of a reliquary, and her gessoed friezes of ethereal spirits brought a flowing, curvilinear dynamic to the insistent verticality of his interiors.

Macdonald’s work, and somewhat less so that of Mackintosh, is loaded with symbolism, but Ms. Helland (who teaches art history at Concordia University in Montreal) and her fellow catalog contributors largely sidestep the issue, perhaps because of the extravagant overinterpretations that have been advanced by some scholars in recent years, particularly those which see the oeuvre of the Four as fairly dripping in sexual meaning. Occult imagery is another possibility that the catalog does not investigate. Although Julian Spalding, director of the Glasgow Museums that together are the largest lenders to the show, believes that Mackintosh and Macdonald’s almost obsessive use of the rose motif points quite clearly to their interest in the Rosicrucian movement, the book makes no mention of that cult, which enjoyed a revival at the turn of the century.4

3.

It is most unfortunate, then, that the version of the exhibition “Charles Rennie Mackintosh” now at the Metropolitan Museum fails to give adequate attention to the two most significant issues whose previous neglect is redressed by the catalog—the necessity of seeing Mackintosh not as an isolated artist but as a highly characteristic product of his time and place, and the importance his wife and helpmate had in bringing his stunningly comprehensive design schemes to fruition. That the show as seen in New York is about 20 percent smaller both in floor space and number of objects displayed is not as disturbing as the fact that almost all of the rejected artifacts were by the least famous three of the Four. Similarly diminished are the sections of the original installation dealing with the wider Glasgow scene. And the new labeling throughout the show (by J. Stewart Johnson, the Metropolitan’s consultant for architecture and design and co-curator of the retrospective with Pamela Robertson of the Hunterian) sticks much more closely to the old Howarth line than does the exhibition catalog itself, an anomalous contradiction of the essayists’ corrective efforts.

The Met show, in any event, is a popular success and it is handsomely enough installed, although it is not as provocatively presented as it was in Glasgow, where the imaginative setting of the exhibition was devised by the design firm Creamuse. There has been an understandable proclivity for the public and critics alike to cast Mackintosh as Scotland’s Frank Lloyd Wright, but despite their shared impulse to create self-contained universes of “total design” there are few legitimate parallels between them. During his long career, Wright executed some four hundred buildings; Mackintosh designed some four hundred pieces of furniture but during his short productive period saw only fourteen of his buildings completed (not counting his interior design commissions). Above all, the seamless flow of interior space that was Wright’s most revolutionary accomplishment is rarely found in the architecture of Mackintosh. Hermann Muthesius, the German architect and writer who was one of Mackintosh’s most avid contemporary supporters, once noted that the Scotsman tended to design individual rooms and then wrap buildings around them. The disjunctive feeling one gets during a walk through even Mackintosh’s masterpiece, the Glasgow School of Art—a series of dazzling but isolated spaces joined with little discernible logic and no continuity at all—bears out Muthesius’s observation all too well.

Furthermore, Wright was astonishingly resilient as a man and artist, transforming himself and his architecture time and again in the face of personal and professional setbacks. One year older than Mackintosh, Wright was one of the very few architects working in the free styles of the turn of the century to carve out a successful new direction for himself, though he, like Mackintosh, suffered enormously as taste shifted toward a new classical revival after 1910. That emergent fashion, and especially the catastrophe of World War I, wrecked a number of other unconventional architectural careers, including those of C.F.A. Voysey and Josef Hoffmann.

In temperament and intensity Mackintosh more closely resembled Wright’s lieber Meister, Sullivan. Both men were immensely gifted ornamentalists, but their sometimes excessive attention to decorative details scared off cost-conscious prospective clients. Despite experience working in corporate architectural offices, they became known as difficult colleagues. The predisposition that both men had to bouts of depression was no doubt exacerbated by their alcoholism, a fatal flaw in a profession where a client’s trust is the prerequisite for getting work.

The downward path of Mackintosh’s career is visible at Auchinibert, the Stirlingshire country house he began to design in 1905 for the Shand family. The building was sited atop a steep slope, but Mackintosh seldom bestirred himself to leave the more comforting attractions of the local pub at the bottom of the hill. There, more often than not, he was found drunk by the exasperated patrons, who eventually fired him and had the job completed by another architect.

If anything, Mackintosh enjoyed the extraordinary forbearance of his small but loyal Glasgow clientele, some of whom indulged his moody and erratic behavior. No doubt his head was turned by the entreaties of his admiring Viennese colleagues, who urged him to resettle in their (supposedly more sympathetic) city, a move precluded by the outbreak of the war. In one of the exhibition catalog’s most astute observations, Gavin Stamp, a lecturer at the Mackintosh School of Architecture at the Glasgow School of Art, writes that “the tragedy of Mackintosh is in part that…Hermann Muthesius and Josef Hoffmann made a brilliant but naive Glaswegian believe that he could play the role of an international figure, thus making him impatient with the environment that had made and sustained him.”

If there is another twentieth-century architect to whom Mackintosh might be more tellingly compared it is, surprisingly enough, Louis I. Kahn. On the surface, an analogy between the decorative suavity of Mackintosh and the Brutalist asperity of Kahn might seem absurd. Yet the buildings of both men were deeply influenced by the monolithic massing and defensive position of medieval Scottish castles. Each architect was highly adept at inventive detailing of a sort particularly admired by their fellow architects. And both Mackintosh and Kahn excelled at dramatizing vertical circulation in their structures, designing staircases with forceful psychological effects not seen since the Age of Baroque.

The east stairway of Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art, which he improvised to connect his original east wing of 1897-1899 to his western extension of 1907-1909, is every bit as mysterious and surprising as Kahn’s famous cylindrical stairway at his Yale Art Gallery addition of 1951-1953. Though the work of both men could often seem awkward and unresolved—the result of a relative lack of experience in both instances, as opposed to the myriad opportunities Wright had to work out his ideas and learn from his mistakes—Mackintosh and Kahn could be uncannily adept at sacralizing the small rituals of daily life. Their

It is easy to like Mackintosh for all the wrong reasons, and thus one of the great pleasures of seeing so much of his work gathered in one place is the opportunity it provides to contemplate the strange distortions and odd contortions of the objects he designed with such evident passion. One of Mackintosh’s most gifted contemporaries, albeit one whose classical sympathies insured the long career denied to the Scotsman, was Sir Edwin Lutyens. After he visited Miss Cranston’s newly opened Buchanan Street Tea Rooms in 1897, Lutyens wrote to his wife that Mackintosh’s interior design scheme was “all very elaborately simple.” It has taken the world a full century now to see how wrong that bon mot truly was.

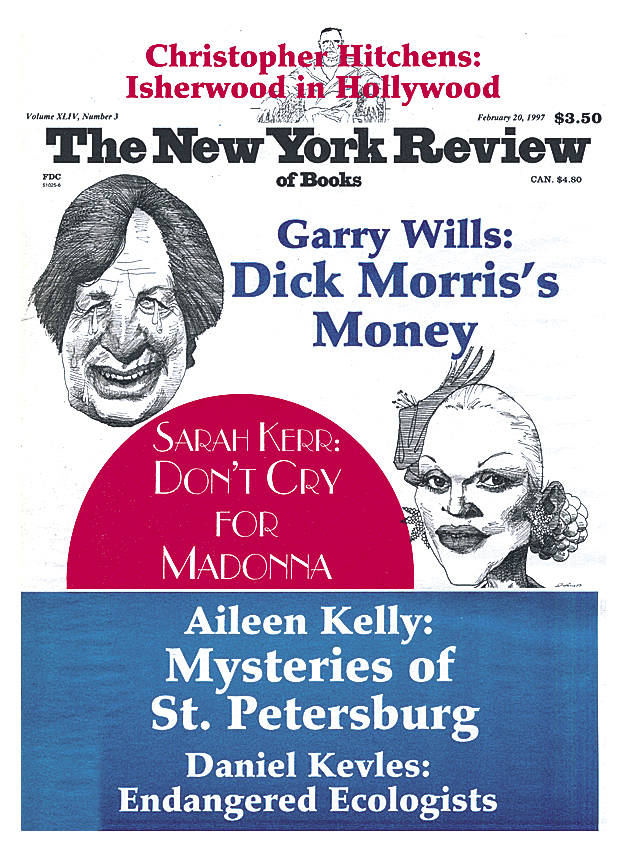

This Issue

February 20, 1997

-

1

Third edition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1990. ↩

-

2

Fourth edition, Penguin, 1974. ↩

-

3

See Martin Filler, “All About Eames,” The New York Review, June 20, 1996. ↩

-

4

See The New York Times, December 22, 1996, letter to the editor from Julian Spalding, Arts and Leisure, p. 40. ↩