One of the many fascinating photographs in Palimpsest, perhaps indeed the most fascinating of the lot, is of the author’s grandfather, Senator Thomas Pryor Gore, having his portrait painted in old age. Reticently distinguished, the subject sits in his chair, ignoring the canvas, a remarkable likeness of him on a properly heroic scale, and presided over by the artist, Azadia Newman, whom we learn was soon to be married to the film director Rouben Mamoulian. The expression on her beautiful face, with its plucked eyebrows, is quite deadpan. Like a portraitist of the Renaissance she is doing her job, and has no special feelings about it or the sitter. But the photograph seems a revelation not only of the society in which Gore Vidal grew up—a very uncommon one in what Roosevelt was even then calling the Age of the Common Man—but of Gore Vidal’s ability to put his reader inside that society, to give us a happy and an unfamiliar sense of familiarity with it.

The reader—the English reader in particular—is here somewhat in the position of one of the characters in Anthony Powell’s long sequence of memoirized fiction, A Dance to the Music of Time. Marrying accidentally into the haut monde, this chap sets himself to find out all about its peculiar ways, while not for a moment aspiring to be part of it himself. Vidal’s skill as a memoirist puts his reader in the same privileged and enviable position. And he is very funny about it. Ever a stickler for elegance of language, he is careful not to use the word “palimpsest” in any merely approximate sense.

“Paper, parchment, etc., prepared for writing on and wiping out again, like a slate” and “a parchment, etc., that has been written upon twice; the original writing having been rubbed out.” This is pretty much what my kind of writer does anyway. Starts with life; makes a text; then a re-vision—literally, a second seeing, an afterthought…, writing something new over the first layer of text…. I once observed to Dwight Macdonald, who had found me disappointingly conventional on some point, “I have nothing to say, only to add.”

It might well have amused Proust, a great palimpsester, to have made a rather similar claim. And for the memoirist-novelist, as Proust and Powell would have agreed, the most essential thing is humor. True snobbery is always solemn. After the wedding of Vidal’s half-sister, Nina Gore Auchincloss (her marriage was a failure, “as family tradition required”), Vidal finds himself driving to the reception with the young Jack Kennedy.

In the back of the limousine, Jack and I waved to non-existent multitudes, using the British royal salute, in which the fingers of one hand unscrew, as it were, an invisible upside-down jar of marmalade. Jack thought that Nini had made a mistake in not marrying his brother Teddy. I had no view on the matter. Absently, he tapped his large white front teeth with the nail of his forefinger, click, click, click—a nervous tic.

The reader feels right there, with it and in it; and so effective is the superimposed ripple of Vidal’s style and personality (the palimpsest at work?) that a kind of innocence of absurdity—as with the marmalade jar—easily mingles with an effortless and knowing sophistication. Brought so fascinatingly close to us, the Vidal world seems both exotic and domestic, glitzy and homely, and is presented with a deft economy that is itself highly droll.

That winter Paul and Joanne and Howard and I took a house together in the Malibu Beach colony. Each had a small car. Paul left for Warners at dawn, as that studio was in the far, faraway San Fernando Valley. I left second, to drive to MGM in Culver City. Finally, Joanne made her leisurely way to Twentieth Century-Fox in nearby Beverly Hills…. Weekends, the house was full of people that, often, none of us knew. Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy were often there, as were Romain Gary and his wife, Leslie Blanche, and….

I am at the point I have been dreading: lists of names of once-famous people who mean nothing, by and large, to people now and will require endless footnotes for future historians. One might just pull it off if one had something truly intriguing to say about each name or if I had, like so many contemporary autobiographers, tempestuous love affairs, bitter marriages, autistic children, breakdowns, drugs, therapy, a standard literary life. But I was to have no love affairs or marriages, while casual sex is, by its very nature, not memorable. I have never “broken down” as opposed to slowly crumbling, and I’ve steered clear of psychoanalysts, nutritionists and contract-bridge players. Joanne Woodward and I were nearly married, but that was at her insistence and based entirely on her passion not for me but for Paul Newman. Paul was taking his time about divorcing his first wife, and Joanne calculated, shrewdly as it proved, that the possibility of our marriage would give him the needed push. It did.

Advertisement

In 1958 they were married at last and we all lived happily ever after.

Not only does Vidal have original things to say on many subjects but the reader feels himself becoming one with the characters in the book: a sure sign of a literary master at work. He has, for example, a good point about class. He is amused by the British class system, and by romantic English writers—Auden was one—who loved the idea of America as the classless society while firmly asserting their own status back home (upper-middle in his own case, Auden insisted—he was the son of a doctor). Of course America has its own class system, says Vidal, just like Britain. The difference is that most Americans don’t even know it. The few that do are well aware of the exclusion zones and neatly roped-off areas which it takes either privilege of birth or dazzling social and intellec-tual skills (Vidal had both) to enter and enjoy. Whereas the Englishman knows his place, and is prepared either to put down his inferiors or to be put down—ever so unobtrusively—by his betters, the American really can change his class, if his talents or chutzpah are up to it. All this is very politically incorrect, but it probably happens to be true; and Vidal, as a natural classicist and an admirer of Montaigne and Cicero, thinks it is likely to go on being true.

Incidentally, the “Howard” referred to in the passage quoted above has been Vidal’s almost lifelong companion. “‘How,’ we are often asked, ‘have you stayed together for forty-four years?’ The answer is, ‘No sex.’ This satisfies no one, of course, but there, as Henry James would say, it is.” Howard Auster was born in the Bronx, worked in a drugstore to put himself through New York University, and tried to get a job in advertising. At that time Jewish persons were discouraged in that profession, so Vidal recommended that he change the r at the end of his name to an n. He did so, and was at once taken on by an agency. Class is less visible than racism, but no doubt the two always have and always will be intertwined. (Austen, by the way, or its variant Austin, is a respectable though not a grand name in England, not like Talbot, say, or Villiers. Jane Austen knew her class—roughly upper-middle, like Auden’s—and kept a beady eye above and below it, for like many such families she had some connections grander than herself, and others less grand.)

His needle-sharp curiosity and humor make Vidal a natural enjoyer of all such matters. He revels, as already noted, in a sort of sophisticated innocence. P.G. Wodehouse would have been delighted by the idea of Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward and the author each setting off for their respective studios at different moments in the early morning: yawning, no doubt, as they brushed the crumbs away. A super sophisticate in the public estimation, he has a ruefully witty tale or two to show with what unjust firmness that persona has clung. An actress once told him that everyone knew Noel Coward had one really rather disgusting sexual habit. “I was horrified. I knew Coward well. He was as fastidious about sex as about everything else.” When Vidal saw the actress later she said she’d never forgotten what he had told her about Coward’s sex kink. “Thus I have been transformed into the source of a truly sick invention that will be grist to the Satanic mills of Capotes as yet unborn.”

The two most important people in Palimpsest, and the ones most movingly brought to life, are his Gore grandfather, the senator, and Jimmie Trimble, the fair-haired boy he met in Washington, killed in 1945 with the marines on Iwo Jima. Vidal loved both, and it is love that brings them so much alive in his memoir. Thomas Pryor Gore becomes for us as memorable a figure as the old patriarch grandfather in Aksakov’s well-known memoir A Russian Childhood, but there is nothing patriarchal about him. Rather he is a distant, detached, and slightly sardonic figure, which itself may give a clue to the difference between the naturally big man in a Russian nineteenth-century family and in a twentieth-century American family. Power in an up-and-coming American family was a more subtle affair than it had been in the Russian context, and it had to be more skillfully exercised. Freedom in America was always there for the rest of the family to walk away into if they wanted.

Advertisement

T.P. Gore, in any case, was not inclined to control his family by means of money, or through the prospects of inheritance. He was blind from ten years old: as his grandson says, an extraordinary trick of fate. “The odds are very much against losing an eye in an accident, but to lose two eyes in two separate accidents is positively Lloydsian.” And fate had more freakish adventures in store for him. He was a friend of Clarence Darrow, and at a time when he was visiting one of Darrow’s court cases he was himself about to be tried for rape. He had backed the Indians against the oil interests in Oklahoma, where he was senator, and after ignoring threats to soften up he had the “badger game” played on him. A woman constituent rang him with some request, and after leading him to her hotel room, in the absence of his male secretary, tore her clothes off and started screaming. Two handy detectives rushed in and said, “We’ve got you!”

A jury took ten minutes to exonerate the Senator, who, as it happened, had already once found himself in a “shotgun” situation over a young woman. And she too had been blind. Her family accused him of raping her—the youthful pair were living in the same boarding house in Corsicana, Texas—and demanded marriage. A real shotgun was produced, but the future senator walked away saying, “Shoot, but I’m not marrying her.” The facts of what happened remain obscure, as family facts perhaps always do and should do; but making his own inquiries in later years the grandson found some evidence to suggest that the Senator had indeed been guilty in this instance. Surmounting all the odds he was already on his way to becoming a quietly charismatic personality and a brilliant and dryly Ciceronian speaker; but even he might have been overhandicapped by becoming a partner in a blind marriage. He met his wife—they became known to the family as Dot and Dah—at a political meeting in Texas. After hearing her beautiful low voice he said at once, “I’m going to marry you.”

There is more than filial feeling, strong though that is, in the vivid way Vidal recreates a grandfather who may have meant far more to him than his own father, Gene Vidal, the athlete and airline president. From the Senator, doubtless, came not only the literary gift but the abiding fascination with the personalities of power—power in any era. Reading for hours a day to a grandfather whose affection never took, then or later, the form of gratitude, the seven- and eight-year-old Gore must have unconsciously begun to learn how things go in those power circles. It was to be a lesson put to good and apparently effortless use in the brilliant studies of Caesar and Julian the Apostate, as well as in those of Lincoln and Burr. The young Vidal also saw senatorial ruthlessness in action. If he ever gave up on the reading aloud—always history, poetry, or economics: novels were despised—his grandfather would blithely remind him that both Milton’s daughters themselves went blind, reading to their old tyrant of a blind father.

Language was clearly the Senator’s being. After he had made a fine political oration in Texas a group of Baptist ministers were so impressed that they offered him a fat salary and fine house to become their minister. When he courteously declined, on the grounds that he did not believe in God, they told him, “Come now, Mr. Gore, that’s not the proposition we made you.” The Senator’s own brand of eloquence was what mattered. “Dah,” says his grandson, “had a curious position in the country, not unlike that of Helen Keller, a woman born deaf, mute, and blind. The response of each to calamity was a subject of great interest to the general public, and we children and grandchildren were treated not so much as descendants of just another politician but as the privileged heirs to an Inspirational Personage.”

Jimmie Trimble, appearing, Vidal tells us, in many photos with no smile on his handsome face, and with his eyes looking away, is the image of Delphic Charioteer, or Shropshire Lad, who would have been recognized at once by the poet A.E. Housman. Housman knew that real love was once for all, and that the knowledge went, rather more ambiguously, with an unconscious lust for the loved one’s early death. It did not happen in his case. His fate was to love a young undergraduate who in fact lived a long and useful life, but at least in the poet’s memory he became one with “the lads who will die in their glory and never be old.”

Jimmie was nineteen when he was shot and bayoneted, asleep in his foxhole, by a Japanese raiding party at midnight on Iwo Jima. Vidal is of course fully aware of the irony that now veils the myth of the young dead soldier; but he has the kind of style that can admit all that irony and yet achieve a moving and classic simplicity as well. Jimmie’s single reappearance is both plangent and matter-of-fact, like the visit that Odysseus, after he has drunk the black blood, is permitted to make to the world of the dead. The blood-drinking ritual for Vidal was smoking ganja in Katmandu, “not an easy thing for a nonsmoker to do.”

But as I gasped my way into a sort of trance Jimmie materialized beside me on the bed. He wore blue pajamas. He was asleep. He was completely present, as he had been in the bedroom at Merrywood. I tickled his foot. The callused sole was like sandpaper. It was a shock to touch him again. The simulacrum opened its blue eyes and smiled and yawned and put his hand alongside my neck; he was, for an instant, real in a hotel room in Katmandu. But only for an instant. Then he rejoined Achilles and all the other shadowy dead in war.

Jimmie had been an excellent athlete and a reluctant soldier, who did his best both not to be where he was and not to die where he did. Like Vidal, who was serving as a mate on an army landing craft in the dangerous waters of the Aleutians, he strongly resented the fate that had brought him into war. Had he survived he might never have mattered very much to the author, who dedicated a novel, The City and the Pillar, to him, and who recalls telling an inquisitive journalist that JT “‘was the unfinished business of my life.’ A response as cryptic as it was accurate.” Certainly the living have not the powers of the dead, and power is of course Vidal’s most writerly theme. Finding out about the dead man, chiefly from his mother, after his own brief idyll with the living one, was clearly as important to Vidal’s subsequent and protean development as the relation with his grandfather had been. The City and the Pillar still reads as a most impressive novel, far more powerful and also closer to life than the homoerotic novels of its own or of a previous time. Like the Greeks and Romans, the young Vidal could always find sex at the same time bleak, lyrical, and funny, whatever form it took.

His powers as novelist and writer, not only thoroughbred ones but gifts that are truly his own, are at their strongest in this search for the past which gives us his own family, his Gore grandfather in particular, and his love for Jimmie Trimble. Jealousy, although in this case a retrospective jealousy, is the side of love most familiar to Proust. For Vidal, perhaps, love could only become fully aware of itself when the sources of jealousy were revealed, for others beside the young Vidal had been smitten by Jimmie. Vidal himself was then well able to plunge into a dazzling career of sex, entertainment, and hard work—turning out novels, plays, and filmscripts, even while his unconscious mind was carrying on its “unfinished business.”

The more gossipy and predictable side of Palimpsest is beautifully done, economically funny and elegant, but by necessity a conducted tour rather than what can seem—especially in the first section of the book—a true conversation of discovery with the reader. And yet, as Myra Breckenridge long ago showed, Vidal can be more classically funny than most writers in this vein since Petronius Arbiter wrote of Trimalchio’s Feast. Every page of Palimpsest has some pleasurable absurdity, usually a good-natured one, that stays in the memory, and often with an aroma of poetry about it, as on the pages which return us at intervals to the author’s villa at Ravello, where the memoir is being written. Swimming under the cypresses in the navy-blue pool and rescuing a small drowning lizard, he recalls the exceedingly grubby swimming pool at the Windsor Castle Royal Lodge, where he and Princess Margaret saved a number of bees from drowning, she exhorting them “in a powerful Hanoverian voice” to “go forth and make honey.”

The snapshot of E.M. Forster, patron saint of the English gay community, is not only dreadfully funny but revealing. Forster, as Vidal perceived, held perpetual court in both senses, and his judgments had an “unremitting censoriousness” quite alien to the free and easy living of American gays. Forster twinkled at adoring acolytes like Christopher Isherwood, even while ignoring the book Isherwood had recently sent him. He invited Vidal and Tennessee Williams to lunch at Kings College, Cambridge, for he was shrewd enough to wish to patronize a rising celebrity, even an American one. Williams wisely declined, but Vidal was prepared to undergo a droll experience.

We had a bad boiled lunch. “You must have the steamed lemon curd roll, ” Forster said. But as there was only one portion left, which he so clearly wanted, I opted for rhubarb. “Now,” he said, contentedly tucking in, “you will never know what steamed lemon curd is.”

Forster was also highly secretive. Lionel Trilling had just published a study of his novels but had no idea that their author was queer, and was astounded to be told so by Truman Capote. For once, as Vidal dryly remarks, Capote had no need to be inventive.

At this time, in the late Forties, after The City and the Pillar had become a best-seller on the New York Times list, Vidal “wanted to meet every writer that I admired. I met several; as a result, I never again wanted to meet, much less know, a writer whose work I admired.” But the great exception was Tennessee Williams, “the Glorious Bird.” The essential homeliness, even shyness, of this exotic figure is what comes across in Palimpsest, whether in Rome or New York, or on the Left Bank, as if such descriptions of him might be of Julius Caesar, in a domestic light with his wife Calpurnia. Vidal possesses the gift for seeing life, as it were, on its snug, unbuttoned side, perhaps because, as the Bird once remarked, “Gore gets on even less well with people than I do.” It takes the born outsider, which most good writers are, to show the way of the world unbeglamoured, and as it really strikes them.

Vidal shared rooms on the Left Bank with the Bird in the early Fifties, at a time when both were on the edge of success. An American female academic, who was doing a biography of Tennessee Williams, asked Vidal whether they were lovers at the time. Vidal replied that “in my experience of real life it was unusual for colleagues to go to bed with each other. Of course, I added tolerantly, to show that nothing human was alien to me, I did understand that it was known for tenured lady professors to go to bed with each other….” It was a neat way of turning the tables, and one would like to know what the professor came up with in reply. Palimpsest is much too urbanely written to bother with reticence, but it contains not a hint of either the vulgar betrayal of friends, or a pseudo-radical confession about the self. As the Bird pointed out, intellectuals usually prefer to talk to each other rather than to go to bed together. At least it was so in his case. “‘It is most disturbing to think that the head beside you on the pillow might be thinking, too,’ said the Bird, who had a gift for selecting fine bodies attached to heads usually filled with the bright confetti of lunacy.”

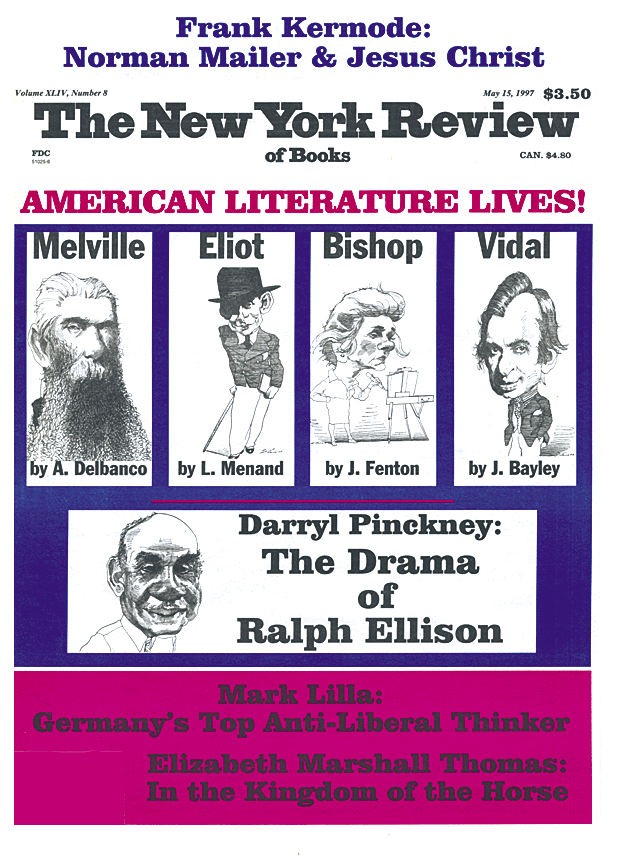

As if he were living in an Elizabethan age, the worlds of fashion and frivolity were as natural for Vidal, given his background, as was the world of politics and power. In Camelot the two were the same, and the Kennedys were typically anxious to meet and to mingle. A photo shows Jack Kennedy with Vidal and the Bird, who have driven up from Miami to greet him. “Far too attractive for the American people” was the Bird’s verdict. That was in 1958, when Kennedy was already running for president. Two years later Vidal himself would be running for Congress in upstate New York on the Democratic ticket. Truman came to help out in Poughkeepsie, remarking “I hope I haven’t done you any harm” as he left. But Vidal’s interest in politics was more that of a writer than that of a dedicated player of the game: his interest in Kennedy, as friend, near-relative, and political phenomenon, was, so to speak, Shakespearean rather than professional. The true goal of Vidal’s politics was surely his own books, particularly Julian, Lincoln, and Burr, which came out of both his own experiences and the feel for things he had acquired at the knee of his senator grandfather.

It is far from easy to say how balanced or how deeply felt is his own political philosophy. The image of Lincoln-Macbeth, the reluctant tyrant agonized by the consequences of his own tyranny, is a striking one, but it may belong more to the study and the theater than to any real political world. On the other hand, Senator Gore used to say, and with some justification, that Lincoln’s sober rhetoric was as inherently meaningless as the flowery sort. “Was there ever a fraud greater than this government of, by, and for, the people? What people, which people?” No wonder that his grandson has considered the greatest presidents to be simply the most Machiavellian, manipulating an attack on Fort Sumter, or on Pearl Harbor, in order to do what they, and not the people, wanted.

If Vidal’s political views are in keeping with his family background there is no doubt about the part their basic assumptions have played in his own career. He once attended a literary conference in Sofia, Bulgaria, at which he encountered that great memoirist, Anthony Powell, together with the English novelist C.P. Snow, who liked to think he frequented in his own fashion the corridors of power. Snow was no match for his Yankee counterpart, who ruthlessly dismissed any genteel plea that the conference might be about “culture.” Authors, like other men of the world, care nothing but for fame and fortune. The enfant terrible who discomfited the English delegates has never been backward about opening his mouth in settings where the conventions of hypocrisy are respected. Goaded in this manner, an exasperated pedagogue at the memoirist’s prep school once told his colleagues that he wanted to be a bull. “So that I could gore Vidal.”

This Issue

May 15, 1997