John Banville occupies a very definite and indeed almost unique place among contemporary novelists. He is not fashionable. Indeed he disregards fashion, even the extent to which most novelists, however independent in their natures and talents, keep an eye on what is “in” or “out,” and are often insensibly influenced by this awareness. He shows no interest in discovering in his fiction who he “really is”; nor does he consciously explore the predicament of a class or a society. Social indignation, or powerful statements about the inner life, are not for him: nor is the fantasy projection of the self that goes with magic realism.

Instead he has thoroughly learned what Henry James called “the Lesson of Balzac.” It was a lesson which James himself mastered, and used with the greatest skill. The novelist, like the scientist, picks his theme, and lets nothing about it be lost upon him. He explores it coolly but imaginatively, without recourse to plotting devices or adventitious effect. The subject may be the natural history of a murder, as in Banville’s The Book of Evidence. It might be the history and implications of a scientific mind and its theory, as with the biographical novel Kepler, themes further taken up in The Newton Letter and in Doctor Copernicus. It might be an oblique study of the world of mythology and belief, as in Mefisto, and in Banville’s recent novel, Athena. Banville is above all a learned novelist, who bears his learning lightly.

His new novel, The Untouchable, takes as its theme the psychology and the natural history of treachery and the treacherous person. In one sense such a subject may seem to belong to the past: since the collapse of the Soviet Union the role of the master spy has been greatly diminished, perhaps even abolished; and with it has gone the fascination the public once felt about such men and their activities. But this does not deter Banville, just as it would not have deterred Henry James. This challenging theme has its own interest, irrespective of its immediate or contemporary relevance: with such a subject men’s motives, their personalities, obsessions, and hidden desires, have a timeless quality. The field in which the classic traitors once operated deserves to be chronicled and comprehended by the imagination, as Balzac once chronicled the corruptions of French society, or Scott the mind and heart of historic legend. The novelist can work in a medium more intuitive than that of the historian, giving his personae from the past a view of their own actions, and a voice of their own.

The past in this novel is not far away, but in our time even the immediate achieves its own kind of distance very quickly. The once-famous traitors—Burgess and Maclean, Philby and Blunt—are already historic figures. It is the last of them that Banville takes as his “hero,” making him the annalist of his own downfall and compiler of the memoir he wishes in his last days, stricken with cancer, to survive him. The same technique was effectively used by Banville on another historic figure, Copernicus; and similar judicious liberties with the facts are taken here but in harmony with history.

The real Anthony Blunt—once Sir Anthony, but his treachery eventually cost him his knighthood—was born, like Kim Philby, in the bosom of the English governing upper class. He was an aesthete and an art expert, who before being demoted had become Master of the Queen’s Pictures and an acknowledged authority on many important painters. Like Philby, he was a Cambridge spy, recruited as a “sleeper” while still an undergraduate, and at a time and place when loyalty to friends and to the ideology of friendship was a paramount feature of the youthful English intelligentsia. E.M. Forster, one of its heroes, had notoriously stated that if he had to choose he would betray his country rather than betray a friend. The act of betrayal required no dramatic decision, no conscious leap in the dark.

Nor of course was it done for money, although the Russian spymasters usually insisted on token payment as a matter of protocol, part of the decorum, as it were, of professional treachery. But Blunt and his fellows were very much amateurs—though Philby at the Foreign Office later acquired a chilling expertise—and it will probably never become clear just how much harm an amateur like Blunt actually did. Before the war the willingness of Blunt and his friends to be recruited was a matter of romantic protest against economic defeatism and depression in England—the graphic background of W.H. Auden’s early poems—and what might be termed a Princesse Lointaine complex in politics. Russia was the unknown wonderful country where people were happy and the future was working. There was also sex. Blunt was homosexual from undergraduate days, and hence habituated to the undercover double life, and to secret protest justified by persecution.

Advertisement

Much of this Banville has altered, but in so subtly imaginative a way that a new character is created who gives his own style of intimacy and individuality to our public portrait of the man on whom he is based. Banville’s Victor Maskell is a Northern Irishman whose father is a bishop in the Irish Protestant Church. He is conditioned to a repressive atmosphere, in a country where repression by an external country, and even more by the Catholic or the Protestant church, has become habitual. Like Blunt he goes to Cambridge, becomes an art expert, makes close friends, is drawn into the atmosphere and the camaraderie of dissent. He is secretly recruited. A slow process of psychological attrition begins.

This would land many novelists in difficulty, for the drama—usually melodrama—that the reader associates with espionage is conspicuously lacking. In real life, of course, the whole process takes place in very slow motion indeed, both invisibly and ambiguously. It is only the highlights that are usually offered to the public, as newspaper stories or later on by the writers of spy thrillers. But there is no field of human activity where the simplifications and stark contrasts of drama are more misleading; and it is this that makes even great classics of the genre, like Conrad’s The Secret Agent, seem in the end artificial, necessarily contrived. For a masterpiece like Conrad’s it is worth paying that price. But lesser spy writers such as Graham Greene try to make a virtue out of necessity by stressing the falsifying artifice of their technique; Greene often referred to the product itself as an “entertainment.”

Banville rightly eschews entertainment. For the reader, the compulsion of his novel is secured by much more convincing and interesting means. Naturally enough the risk is one of monotony. Spies lead day-to-day lives like other people: falling in love, getting married, worrying about friends and family, indulging in routine pleasures. They are also apt to be relentless self-justifiers, and for the fellow at the other end of it such self-justification—whether it takes the form of guilty deprecation or of boasting—can easily become the most boring thing in the world. And yet all these formidable hazards Banville has miraculously managed to turn to his own writerly advantage, so that his reader remains gripped, not by a dramatic tale but by the gradual unfolding of a personal history, a kind of home movie or album of self-taken pictures. How is it done?

Banville has always been a fastidious writer, but the manner in which he has chosen to explore this latest theme presents the greatest challenge he has faced yet to his own virtuosity of style. In a sense his greatest display of virtuosity can show itself in a successful downplaying of things, as in his description of Maskell’s encounter with a doctor, after his treachery has been revealed and his disgrace made decorously public.

Old age, as someone whom I love once said, is not a venture to be embarked on lightly. Today I went to see my doctor, the first such visit since my disgrace. He was a little cool, I thought, but not hostile. I wonder what his politics are, or if he has any. He’s a bit of a dry old article, to be honest, tall and gaunt, like me, but with a very good line in suits: I feel quite shabby beside his dark, measured, faintly weary elegance. In the midst of the usual poking and prodding he startled me by saying suddenly, but in a tone of complete detachment, “Sorry to hear about that business over your spying for the Russians; must have been an annoyance.” Well, yes, an annoyance: not a word anyone else would have thought of employing in the circumstances. While I was putting on my trousers he sat down at his desk and began writing in my file.

“You’re in pretty good shape,” he said absently, “considering.”

His pen made a scratching sound.

“Am I going to die?” I said.

He continued writing for a minute, and I thought he might not have heard, but then he paused and lifted his head and looked upward as if searching for just the right formula of words.

“Well, we shall all die, you know,” he said. “I realise that’s not a satisfactory answer, but it’s the only one I can give. It’s the only one I ever give.”

“Considering,” I said.

He glanced at me with a wintry smile. And then, returning to his writing, he said the oddest thing.

“I should have thought you had died already, in a way.”

I knew what he meant, of course—public humiliation on the scale that I have experienced it is indeed a version of death, a practice run at extinction, as it were—but it’s not the kind of thing you expect to hear from a Harley Street consultant, is it.

Style here is all the more masterly for not being on view. The social implication of the passage suggests the whole world in which Maskell/Blunt has moved and had his precariously elegant being, but the suggestiveness is deliberately kept unobtrusive; except, perhaps, to a connoisseur of Banville’s wide range of aesthetic effect. It is a stylistic tradition that goes straight back to James Joyce, who used all the resources of language to reveal the richness of the most ordinary and homely daily experience. Banville uses them here to explore the edgy boredom, with nothing thrilling about it, of having to lead a double life; and the even more desolating and solitary boredom awaiting the agent who has been “blown” but left contemptuously in place: a pariah who for a number of reasons is not even worth awarding the martyrdom of prosecution. The novel, as a case history, is anticlimactic, and yet just as Joyce is never banal as he explores the dailiness of our daily routines, so Banville is never boring as he leads us from day to day through the dreary corridors of espionage. He has no melodramatic gambit in store—he does not need one—and no contrived dénouement in the style of Ambler or Le Carré: such things do not go with the real work the spy is doing, or with any true exploration of it.

Advertisement

Instead he deftly imagines and reveals a patrician world and class which have lost their nerve and know it. Being Irish himself Banville may be taking a sly pleasure here in English social and political embarrassments, as he may do also in the fact that his hero’s father, the upright man, is a Protestant bishop in the Church of Ireland, not the Roman Catholic Church. If so it is a private joke, for the ordinary reader will have no trouble in accepting what is in fact the highly implausible scenario of an Ulsterman at ease among the English spying coterie, who hang together by reason of class and background. If it is a private joke it is not the only one. The novelist Graham Greene makes a thinly disguised appearance as the odious Querell, another English spy who has been in the spy business longer than Maskell himself, and there is a good deal of vindictiveness in this mordant sketch by Banville of a novelist for whom he clearly feels no affection.

The real Graham Greene liked to hint, no doubt out of vanity, that he was not only familiar with the world of espionage but had participated in it. He had certainly known Burgess and Maclean and their friends, and worked himself briefly for MI5 during the war, though only in an innocuous role. Querell, however, both cuckolds and betrays Banville’s hero, perhaps because the latter despises the spy stories that he writes (“…That thriller of his about the murderer with the club foot. What was it called? Now and in the Hour, something pretentiously Papist like that.”) The detestable Querell remains triumphantly unsuspected (writing spy stories would be excellent cover for a real spy?) and appears like death itself at the book’s ending, waving a sardonic farewell to the hero, who is himself on the edge of death. His world is in ruins. His children may not be his own, and even his precious picture by Poussin turns out to be probably a fake.

It appears too that yet another man remains unexposed, a shadowy figure of such eminence in the British Conservative establishment that he is literally “untouchable.” But as with the Graham Greene ploy these nods and hints appear over-contrived—Henry James would not have approved of them in a novel with such a sober and intelligent approach—and it is no less than a compliment to Banville’s book to point out that such occasional devices represent its weakest side. However many hidden higher-ups may remain unrevealed, the real imagination of the book goes into its sense of events in the past. All these doings seem very long ago, and hardly even very real anymore. Banville turns history into the kind of reality which can be possessed by the novel as a work of art.

Spain, the kulaks, the machinations of the Trotskyites…how antique it all seems now, almost quaint, and yet how seriously we took ourselves and our place on the world stage. I often have the idea that what drove those of us who went on to become active agents was the burden of deep—of intolerable—embarrassment that the talk-drunk thirties left us with.

That sense of futility haunts the novel, and in his unobtrusive way its author draws it forward into our present age—into any age—by indicating how perennial is the gap between those who talk and those who act—and adding the grotesquely true paradox that some are driven to the latter course merely by a sense of shame at their own impotence as chatterers and theorists. Active treachery is at least doing something, giving an active idealist the illusion of bringing society nearer to the Promised Land—the Promised Land Maskell would never reach, and never really wanted to reach. The members of any such dedicated, secular body, among the few that are left today—the ETA, the IRA, and a few others—are doing their thing for its own sake, and resolutely refusing to face the consequences for themselves of their dream’s fulfillment.

Burgess and Maclean escaped to Moscow in 1951, a more sensational event at the time than the later defection of the much more damaging traitor Kim Philby, who does not appear in the book. The other couple, who had always been absurdly indiscreet, were on the verge of being picked up by the counterespionage authorities. Unlike Philby, or Maskell/Blunt, they were also picturesque figures, whose sexuality and drunkenness could be gloated over by newspapers and public. Banville is very successful in creating Victor Maskell (“code-name John”) and beguiling us throughout a longish first-person novel with the way he talks, thinks, and behaves. Maskell himself is fascinated by the personality of “Boy” Bannister, a creation based on the real Burgess, just as Maskell himself is based on the real Blunt. Burgess was a legendary figure, appearing in many memoirs of the time. A Falstaffian bisexual, he was habitually drunk and reckless, but his charm protected him by ravishing most people with whom he came in contact, women as well as men. The “Boy” even appeals to the pregnant wife of one of Maskell’s spy colleagues.

We climbed to Nick’s rooms and found Baby, in a smock, big-bellied, sitting in a wicker armchair by the window with her knees splayed, a dozen records strewn at her feet and Nick’s gramophone going full blast. I leaned down and kissed her cheek. She smelled, not unpleasantly, of milk and something like stale flower-water. She was a week overdue; I had hoped to miss the birth.

“Nice trip?” she said. “So glad for you. Boy, darling: kiss-kiss.”

Boy lumbered to his knees before her and pressed his face against the great taut mound of her belly, mewling in mock adoration, while she gripped him by the ears and laughed. Boy was good with women. I wondered idly, as I often did, if he and Baby might have had an affair, in one of his hetero phases. She pushed his face away, and he rolled over and sat at her feet with an elbow propped on her knee.

Domestic and period aspects of the story are vividly sketched; and there is a good deal of history and action thrown in as well—Dunkirk; Bletchley Park, the code-breaking center; a panorama of the last great war—but recalled with a certain absentmindedness which brings us back to the narrating hero’s present fate as an outcast and solitary, as untouchable as the mysterious grandee whose social and political status means that he never has been and never can be unmasked. The title has a triple ironic twist, referring as it does simultaneously to this figure, to the whole caste of untouchables shunned by society, and to a special criminal status in which the guilty man is revealed but left alone. Blunt was publicly exposed but never punished or prosecuted, seemingly because of his social status, and his once close connections with the Royals as their art expert. A man of great charm himself, he had been a friend both of the Queen and of her father, King George VI, with whom the young Victor Maskell has in the novel a notable and almost Shakespearean interview. Indeed Banville’s technique in exposing the progress of this unusual spy is to let him chronicle the events of his own life in a series of brilliant portraits and life studies not so unlike the multiple succession of scenes in the playwright’s historical chronicles. Although sedulously avoiding any contemporary version of spy-style drama, Banville employs the traditional kind of account to great effect.

Blunt was homosexual and a bachelor. Maskell is married, although his mode of life makes him not unduly in love with domesticity. His “friends” are either the professionals who are periodically recalled into Russia, usually never to be heard of again, or his own amateur colleagues, like Boy Bannister. It is this last who turns out, after his flight to Moscow, to have left Maskell an unusual legacy in the shape of a young man called Danny, an expert but genial practitioner of the homosexual “rough trade.” In his isolation and his inner exile, condemned to continue with his “normal” life as a professor and aesthete while being shunned by all, Danny constitutes for Maskell a kind of ironic lifeline back to humanity. This sexual transformation in himself, observed by Maskell with his own sort of wry and urbane intelligence, becomes in his singular circumstances both moving and convincing. So is the picture of Danny.

Immediately, like a fond old roué, I sought to introduce Danny to what used to be called the finer things of life. I brought him—my God, I burn with shame to think of it—I brought him to the Institute and made him sit and listen while I lectured on Poussin’s second period in Rome, on Claude Lorrain and the cult of landscape, on François Mansart and the French baroque style. While I spoke, his attention would decline in three distinct stages. For five minutes or so he would sit up very straight with his hands folded in his lap, watching me with the concentration of a retriever on point; then would come a long central period of increasing agitation, during which he would study the other students, or lean over at the window to follow the progress of someone crossing the courtyard below, or bite his nails with tiny, darting movements, like a jeweller cutting and shaping a row of precious stones; after that, until the end of the lecture, he would sink into a trance of boredom, head sunk on neck, his eyelids drooping at the corners and his lips slackly parted. I covered up my disappointment in him on these occasions as best I could. Yet he did so try to keep up, to seem interested and impressed. He would turn to me afterwards and say, “What you said about the Greek stuff in that picture, the one with the fellow in the skirt—you know, that one by what’s-his-name—that was very good, that was; I thought that was very good.” And he would frown, and nod gravely, and look at his boots.

As with his study of a murderer, The Book of Evidence, there is about Banville’s method his own highly original style of detachment. True, there are moments in all his novels when this technique seems to be enjoying itself for its own sake; and moments when Banville seems deliberately to wear what Elizabeth Bowen memorably described as a face not infrequently to be met with in Ireland—“an unkind Celtic mask.” But on the whole the author’s pose is not unlike that of his own consultant physician in The Untouchable: dry and humorous, a little world-weary, but by no means inhumane. Above all, highly individual. In an age in which conventional pieties and a standardized “seriousness” have tended to rob the novel of the lightness and capacity for surprise which should be its great asset, Banville’s books are not only an illumination to read—for they are always packed with information and learning—but a joyful and durable source of aesthetic satisfaction.

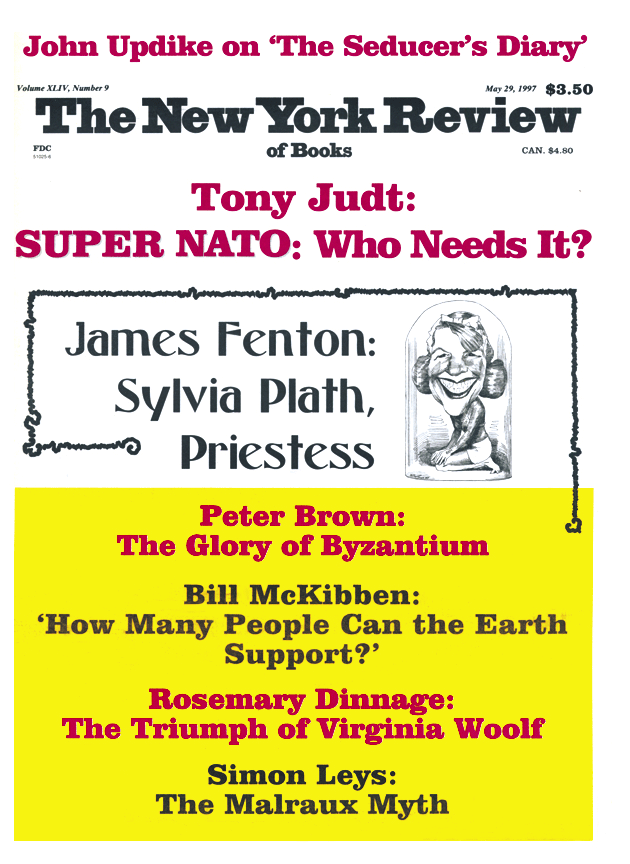

This Issue

May 29, 1997