The first things that struck Princess Victoria favorably about her German cousin Albert on his visit to England in 1836 were his “beautiful nose” and his “very sweet mouth with fine teeth.” Victoria noticed such things. She was very fond of male beauty. Just before Albert’s visit, with his brother Ernst (“fine dark eyes and eyebrows, but the nose and mouth are not good”), to celebrate Victoria’s seventeenth birthday, she had dismissed two Dutch princes presented to her as potential suitors. “The [Netherlander] boys,” she wrote to her uncle, King Leopold of Belgium, “are very plain.” She thought their faces showed an unpleasing mixture of Dutch and “Kalmuck,” or Mongol, and “moreover they look heavy, dull and frightened and are not at all prepossessing. So much for the Oranges, dear Uncle.”

The stream of young men paraded before the princess, to have their physical charms appraised, brings to mind not so much a royal match as a well-appointed brothel, where pretty dances, fine clothes, and elegant small talk only serve to add some class to what is, after all, a sexual transaction. Albert was destined to be a high-class stud, a robust bedroom performer, guaranteed to produce plenty of blue-blooded offspring. That was his main duty; indeed, it was virtually his only duty. Parliament voted against his becoming King Consort or even getting a British peerage. And yet, by the end of his short life, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha had exerted a huge and lasting influence on British life. Most of the qualities we still regard as typically “Victorian,” the high-minded patronage of science, the museums, the charities, the sentimentality, the domestic monarchy, the Christmas tree, the industrious do-goodery, and even the prudery, were stamped with Albert’s mark.

Stanley Weintraub has written a dense, detailed, sympathetic account of Albert, who is not an easy subject for a biographer, since he was a worthy but not a glamorous figure. His achievements were extraordinary, yet he lacked color, or dash, or charisma, or whatever it is that quickens our imagination. Worthiness, even on a heroic scale, is not sexy. Albert is most interesting for what he represented, inspired, and sparked off in others. Albert, in a way, is history’s straight man—Victoria, of course, was a comedienne of the first order. One thing he inspired all his life was British or, more especially, English xenophobia. This is well recorded by Weintraub, who manages to write about the less pleasant aspects of the English without losing his sense of comedy. The other thing Albert inspired was Victoria’s ardor. It is astonishing to see how much a period associated with highmindedness and prudery was actually shaped by the Queen’s passion for the male sex. The prudery was surely more Albertine than Victorian.

Before marrying Victoria, Albert didn’t have much of a track record as a lover; in fact he had none. This was unusual for a young aristocrat. But girls seem to have put Albert off from an early age. Lytton Strachey, admittedly not always the most scrupulous of biographers, recounts that Albert, aged five, “screamed with disgust” when he was asked to dance with a little girl.1 Later events make this story sound plausible. When Albert visited Italy as a young man, he spent all his time at a ball in Florence talking to an elderly scholar, instead of mixing with the ladies. Observing this behavior, the Grand Duke of Tuscany remarked: “Here is a prince we can be proud of, la belle danseuse l’attend, le savant l’occupe.”2 Albert’s father, a man of the old school who spent much of his time, as Weintraub puts it, “wenching,” took his son to take the waters at Karlsbad, where there would be ample opportunity for wenching. Albert didn’t wench, but preferred to stay in his room studying English. Lord Melbourne, prime minister at the time of Victoria and Albert’s marriage, and another rake of the old stamp, told the young Queen that her future consort’s “indifference about ladies” was perhaps “a little dangerous.”

And yet we have a great deal of evidence, provided by Weintraub, among others, including Queen Victoria herself, that Albert was an ardent lover. Or if he wasn’t, he certainly put up a good show. About her wedding night, the Queen wrote in her journal: “When day dawned (for we did not sleep much), and I beheld that beautiful angelic face by my side, it was more than I can express! He does look so beautiful in his shirt only, with his beautiful throat seen.” Lest this sound like a one-sided expression of worship, she also wrote that “his excessive love” gave her “feelings of heavenly love and happiness,” and that Albert “clasped me in his arms, and we kissed each other again and again.” It is hard to imagine the present British monarch expressing herself in similar terms.

Advertisement

Weintraub mentions such details as the device at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, which enabled the lovers to lock their sound-proofed bedroom from the inside, without moving from their bed. Then there was their shared taste in art. Both Victoria and Albert enjoyed sculptures and paintings of nude men and women in erotic poses. Victoria gave Albert a gilded silver Lady Godiva for his birthday. She liked to commission male nudes from such artists as William Mulready, Daniel Maclise, and other specialists in the softly pornographic genre. Maclise’s A Scene from Undine, full of wriggling naked water nymphs, was a favorite, as was Anton von Gegenbaur’s Hercules and Omphale, which hung in Albert’s bathroom. This painting of Omphale, Queen of Lydia, wearing nothing but a headscarf, cradled on the massive thigh of an equally naked Hercules, whom she had bought as her slave, is seen by Weintraub as particularly significant. Hercules was Omphale’s sex slave, but, “foreshadowing Albert’s public role, the Omphale- Hercules relationship also represented a stage in the shift from matriarchy to patriarchy, for as the Queen’s consort Hercules often ceremonially deputized for her.”

One has to be careful about analyzing taste in other periods. People in the 1840s may not have looked at pictures of nude queens dandled by muscle-bound slaves in the same way we do. It is difficult for us to see a Maclise or Gegenbaur without thinking of Vargas girls and Playboy magazine. To project such associations on the past would be a mistake. Yet the royal gaze cannot have been wholly innocent. Ruskin described Mulready’s nudes, which gave the Queen such pleasure, as “degraded and bestial.” The least one can say is that Victoria, and Albert too, took a sensual delight in married life, which is at odds with the received image of “Victorian” prudery.

One of the myths of the Victorian age was that men could enjoy sex, but women only endured it (and thought about England) for the sake of procreation. Men liked wenching, mostly paid for, while women found their fulfillment in family life. This does not apply to Victoria, however, who craved Albert’s amorous attentions, but loathed the consequences. Far from being a loving matriarch, Victoria couldn’t stand babies (“frightful when undressed”), and saw as little as possible of her children—once every three months was deemed quite sufficient. When her daughter Vicky was pregnant with her first child, the future Wilhelm II of Germany, Victoria wrote to her that this was “horrid news.” Given what we now know about the Kaiser as a warmonger, she had a point, but that was not quite what she meant.

However, about Victoria’s abiding passion for Albert and its carnal nature, there can be no doubt. When her doctor advised her that abstinence might be in order, after having given birth to nine children, Victoria is said to have exclaimed: “Oh, doctor, can I have no more fun in bed?” She had loved men before she met Albert, and would do so after his death, even if her passions remained chaste. Before she met Albert, crowds in London called her “Mrs. Melbourne,” because of her devotion to Lord Melbourne, which one contemporary observer described as “sexual though she does not know it.” After Albert’s death, similar crowds called her “Mrs. Brown,” because of her unusually close relations with her Scottish servant, John Brown. Then there was the dazzler himself, Benjamin Disraeli. And for diversion there were some splendid specimens of Indian manhood serving at her court. Queen Victoria may have been imperious, but she liked to be treated as a woman. Disraeli understood that; Gladstone, for one, did not.

What about Prince Albert? There is no sign of any sexual interest, apart from his wife. One of the reasons English aristocrats never warmed to him, to put it mildly, was precisely because of that. “His virtue,” Weintraub quotes someone as saying, “was, indeed, appalling; not a single vice redeemed it.” Lord Melbourne, whose tastes and morals were more Regency than Victorian, complained to Queen Victoria that nobody showed any gaiety any more. The new sobriety, the stress on hard work, the earnest religiosity that marked the second half of the nineteenth century cannot be blamed entirely on Albert, to be sure. Protestant ethics, especially of the rather low-class Methodist variety, were spreading. Solid bourgeois virtues, rather than aristocratic frivolity, increasingly set the tone. The Victorian monarchy was to become its prime symbol. But, again, it would be more accurate to call it Albertine, rather than Victorian, for it was he, rather than she, who not only personified the virtues associated with his age, but had, as it were, been born with them. Before she met her consort, Victoria had been a party girl who loved nothing more than to dance into the early hours. This was at the time when Albert turned down dancing partners, and preferred to improve his mind.

Advertisement

Albert’s English critics blamed his stiffness, his seriousness, his “cleverness,” and all the other things they didn’t like, on his German background. When we consider that his father was a rake, his mother a disgraced adulteress, and his brother a pleasure-loving ladies’ man, this seems a little unfair. And what German qualities he brought to Britain were mostly beneficial. He modernized the armed forces, at a time when most British generals were mentally stuck in the Napoleonic wars. He helped to make the British take science and technology seriously, when such things were regarded as vulgar, newfangled nonsense by the squires and landed nobles. Without Albert, there would have been no Great Exhibition in 1851, showing off Human Progress through industry and art. “God bless my dearest Albert,” exclaimed the Queen, much moved on the opening day, “& my dear Country which has shown itself so great today….”

The German prince also came up with some distinctly un-Germanic innovations. It was Albert who suggested to the Duke of Wellington that dueling in the military should come to an end. And far from introducing Prussian militarism to the land of shopkeepers, Albert’s influence on British foreign policy was liberal, moderate, and reasonable. When the bluff, popular, “typical Englishman” Lord Palmerston rattled sabers, Albert would often stay his hand. When European monarchies, clinging to absolute power, were rocked by revolutions in 1848, Albert subdued similar sentiments in Britain by turning the British monarchy into a kind of charity enterprise, a dispenser of good and noble works. Albert’s dream, by no means a despicable one, was to forge an alliance between liberal England and a liberalized, Anglophile Germany. It was not to be, alas. And no matter how many ships he launched, houses for the poor he designed, or foreign crises he diverted, Albert remained a foreigner in England, ridiculed in such John Bullish publications as Punch, despised by the huntin’ and shootin’ classes, and made the butt of popular scorn.

Foreign Albert, who went hunting in odd outfits with high Germanic boots, and spoke ponderously in a thick German accent, was a convenient target for people who felt uneasy about social and political change. Britain in the middle of the nineteenth century was subject to deep changes. And Albert associated himself with many of them. The greatest shift was perhaps the transfer of influence and power from landed gentry to urban bourgeoisie. Albert was on the side of the free-traders and industrialists. In describing its taste and inclinations, Weintraub is right to call Victoria and Albert’s court a “bourgeois monarchy.” Whether he is also right to call it a “democratic monarchy” is less obvious. But in any case, just as British conservatives today like to blame all unwelcome changes on “Europe,” some Victorians blamed Albert’s Germanness for the jolts and stresses of their time.

Albert’s burden was exemplified by his conflict with Lord Palmerston, or “Pilgerstein,” as the royal couple privately called him, without affection. Pilgerstein, a wencher, a swashbuckler, a roast beef and old England grandee with the common touch, was, as Lytton Strachey says, “the very antithesis of the Prince.”3 Palmerston was prepared to bully and threaten foreign governments in the name of British liberty. “England,” he liked to say, “is strong enough to brave consequences.” Albert preferred a more cautious approach. This came to a head in the 1850s, when British war fever against Russia was at its height. Russia had attacked Turkey and was pushing the frontiers of its empire westward. Palmerston wanted to stop the Russian Bear in its tracks. Albert, as well as the prime minister, Lord Aberdeen, preferred to avoid a war, for which British military forces were inadequately prepared. But the British people had been whipped into a frenzy. When Palmerston resigned, Albert was accused of being a traitor, a Russian agent, a foreign meddler in British affairs. Weintraub quotes an article in the Daily News: “Above all, the nation distrusts the politics, however they may admire the taste, of a Prince who has breathed from childhood the air of courts tainted by the imaginative servility of Goethe.” And the rabble in London sang:

We’ll send him home and make him groan,

Oh, Al! you’ve played the deuce then;

The German lad has acted sad

And turned tail with the Russians.

As it turned out, the Crimean War was a bloody disaster. And the Palmerstonian press had behaved disgracefully toward a prince who had tried to act in Britain’s best interests. But to see Pilgerstein’s conflict with Albert entirely in terms of English jingoism versus Albertine good sense would be wrong. For there was a serious constitutional issue at stake, which divided the prince from the politician. Albert, following the advice of his German mentor Baron Stockmar, and indulged by the Queen, did indeed take a rather Continental view of the monarch’s duties. He believed that the sovereign had to “watch and control” the government. He saw himself as the Queen’s “permanent minister,” in which function he not only took an active part in political affairs but sought to have Palmerston, or anyone else he disagreed with, dismissed from office.

When Weintraub writes about Albert’s “democratic monarchy,” I assume he means that Albert was more compassionate about the poor than were most Whig or Tory toffs. But Palmerston was surely more democratic than the prince when he insisted that government policy should be the province of elected ministers, and not of the Queen or her consort. Albert’s status as a “permanent minister” was an unconstitutional fiction. But since Victoria left all political affairs to him, he wielded a great deal of power in her name. As Disraeli remarked—with approval—after Albert’s death: “With Prince Albert we have buried our Sovereign.” But then Dizzy was never much of a democrat.

Albert’s power was partly the result of his own prodigious energy and enterprise, but also of his wife’s devotion. All her life, Victoria liked to depend on the men she adored. Thus the German stud without any formal authority ended up with all the authority of an English queen. This may be a sign of a new bourgeois attitude, or, as Weintraub has it, a shift from matriarchy to patriarchy. Or it may have been the need of a woman, who grew up without a father, to fall in love with father figures. (Albert, who grew up without a mother, may have had similar inclinations the other way round; no wonder they hit it off.) Whatever it was, it does seem to show the extent to which public affairs were affected by the private passions of a very ardent woman.

2.

Queen Victoria’s passion is what the movie Mrs. Brown is all about. The story begins during the long extended period of mourning for Albert, when the Queen had retreated for years from worldly affairs. At first she had missed him for typically sensual reasons. As she wrote to her daughter Vicky (quoted in Weintraub’s book): “My warm passionate loving nature [remains] so full of that passionate adoration for that Angel whom I dared call mine. And at forty-two, all, all those earthly feelings must be crushed & smothered & the never quenched flame…burns within me & wears me out!” But soon grief turned into a kind of death cult, a wallowing in morbid introspection, a love of black crepe for its own sake. The Queen’s subjects were getting restless. If she refused to emerge into the world of the living, the monarchy itself might be in danger. And so her courtiers decided it was time to produce a man to revive her spirits. The man they chose was John Brown, the rough, bearded Scottish ghillie who had given the Queen and her consort so much good cheer in the Scottish Highlands before.

Brown, as the Queen noted in a letter to King Leopold, was her “special ghillie,” who “combined the offices of groom, footman, page, and maid, I might almost say, as he is so handy about cloaks and shawls….”4 Physically, Brown was much more like the Hercules in Gegenbaur’s painting than Albert was. He was tall, strong, and blessed with a strong chin, a feature the Queen particularly admired. Acting in the tradition of the court jester, he took gruff liberties that allowed the monarch to relax in his presence. He was able to get away with behavior no other person—even including, perhaps, the late Albert—could have contemplated. “Hoots, then, wumman,” he was overheard shouting, as he helped the Queen wrap her shawl, “can ye no hold yerr head up?”5

After Albert’s death, Brown made himself indispensable to the Queen by protecting her from various mishaps. Once, when the leading horse on a royal trip through the Highlands fell, Brown saved a tricky situation by sitting on its head to stop the panicked animal from doing damage. On visits abroad, he insisted that all the protocol of Balmoral be preserved, as though they had never left home. He loathed foreign food, foreign weather, foreign smells, and probably foreign people too, and sought to protect his sovereign from all these discomforts. When a German guard at Coburg banged the drum while presenting arms to the visiting Queen, a tired Victoria wished the noise would stop, and Brown silenced the drummer by shouting, “Nix boom boom!”

Victoria not only admired Brown for his virile strength, his brusque manner, and what she saw as his typically Highland poetic nature, but she also believed he had peculiar spiritual powers which had enabled him to predict Prince Albert’s death. The fact that he was a drunk who was often too “bashful” (i.e., smashed) to perform his duties she chose to ignore. For she had decided to depend on Brown, in the way she had depended on other men before, and after.

John Brown, then, was a richly comic character, and it was a good idea to cast the Scottish comedian, Billy Connolly, in his role for the movie. He plays him beautifully. Judy Dench, as Victoria, is also well cast, and she makes her passionate dependence on Brown look entirely plausible. And yet there is something missing in the film. It is flat. Victoria’s emotions are there, and so is Brown’s fanatic devotion to his Queen. What is missing is precisely the humor, the comedy of the royal love affair with Highland Scotland, the Victorian, or indeed Albertine, fantasy often described as Balmoralism.

Balmoral, the actual castle, its interior, and the life around it, which included colorful figures like Brown, was largely Albert’s creation. He needed a refuge from London, with its bilious critics, its xenophobic intrigues, its supercilious drawing-room manners, and its enervating metropolitan politics. And the Scottish Highlands, which reminded him of his childhood in Thuringia, was the perfect spot. He likened Balmoral to Schloss Rosenau, where he grew up. No wonder, because Rosenau was built in the mock-Gothic style of a Walter Scottian fantasy. Albert’s father, the Duke of Saxe-Saalfeld-Coburg, had given costume balls there, with guests appearing as characters from Scott’s Waverley novels. To Albert, Scotland was, above all, gemütlich. To sit with Victoria on long winter nights, with a Gaelic dictionary on their tartaned knees, in a room filled with silver thistles, stags’ heads, and tartaned rugs, walls, and curtains, all of Albert’s own design, was gemütlich. And it was especially gemütlich to cavort with Highlanders, who, the Queen noted, were always “cheerful, and happy, and merry, and ready to walk, and run, and do anything.”6

One of the things they did was play out elaborate fantasies, pretending that the Queen and consort were not who they were. Brown and another ghillie called Grant would take Victoria and Albert on Highland expeditions. This is how the Queen described one of them, in the company of Lady Churchill and General Charles Grey: “We had decided to call ourselves Lord and Lady Churchill and party—Lady Churchill passing as Miss Spencer and General Grey as Dr Grey! Brown once forgot this and called me ‘Your Majesty’ as I was getting into the carriage, and Grant on the box once called Albert ‘Your Royal Highness,’ which set us off laughing, but no one observed it.”7

To Victoria and Albert, Scotland was really a land of make-believe, their version of Marie-Antoinette’s farm cottages at Versailles (which were inspired, in turn, by a pastoral English fantasy). Post-Albertine Balmoral was not so much fun anymore, of course, but much of the Scottish fantasy survived, particularly in the figure of Brown. One of his attractions for the Queen was his former closeness to Albert.

The Highland romance was profoundly unpolitical, even anti-political. Scotland was a playground without politics. Recent popular demands for a Scottish parliament suggest that Scots have become tired of such fantasies and want a political identity of their own.

But the Victorian fantasy could have been exploited better in the movie. With a lighter touch and more sense of humor, Mrs. Brown could have been a comic masterpiece. Instead, John Madden and his scriptwriter chose a more conventional path, which might be termed “Hollywood post-colonial,” even though the film was produced by BBC Scotland. Brown is shown as a true man of the people, the salt of the Scottish earth, whereas Victoria’s English courtiers are all stuck-up, tight-lipped, wholly unsympathetic cartoons of English snobbery. The Queen’s private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, acted by Geoffrey Palmer, is a particularly unfair caricature. For in fact he was not a cold, disdainful enemy of Brown at all, but a humorous, liberal-minded man, who got on very well with the ghillie. But in Hollywood post-colonial—think of Braveheart, or any number of films about Ireland—the English have to look bad. As a result, the movie seems to take the royal Scottish fantasy at face value.

Brown did pose a genuine problem, which was a minor variation of the Albert problem. Personal access to the Queen gave a person a great deal of power and influence. Brown was not only able to organize Victoria’s schedule at Balmoral and other royal palaces, but was sometimes consulted on political affairs too. Naturally, his influence was nothing like Albert’s, but his proximity to the throne was nonetheless irritating to others, including the Queen’s own children, at a time when the Queen was a virtual recluse. One man who saw the situation clearly, and knew just what to do, was Disraeli (played in the film with hammy skill by Antony Sher), who would send polite messages to Balmoral addressed to Mr. Brown.

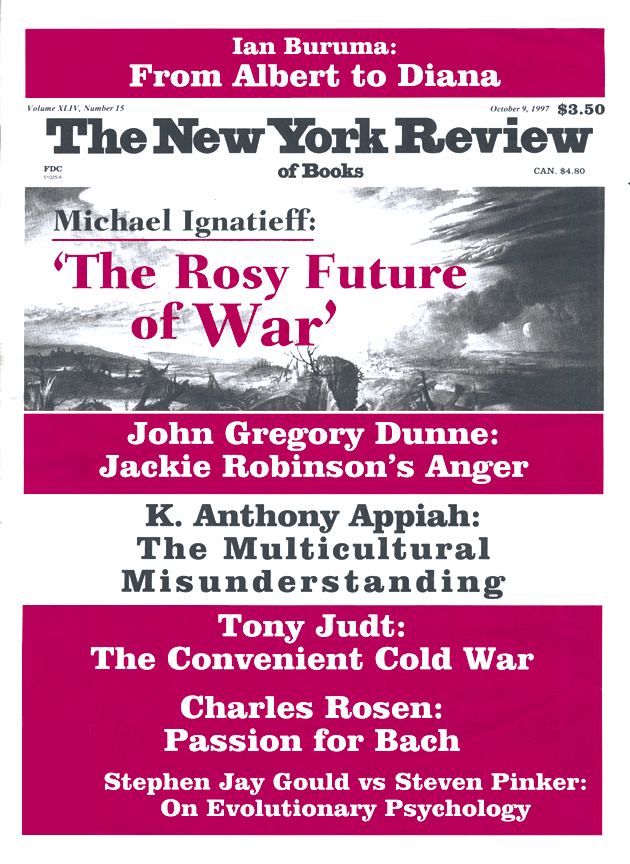

Queen Victoria was not the last member of the royal family to outrage and entertain the British nation with her affairs of the heart. As I was reading up about John Brown for this article, the British tabloid press (and increasingly the “serious” broadsheet papers too) were running front-page stories every day on the state of affairs between Prince Charles and his lover, and Princess Diana and hers. By the time I finished, there was even more coverage of the late Princess. In one week she had become a secular saint. Some parallels with the past are indeed striking. (See opposite page.) I’m not sure whether one would call Diana’s new saintliness Albertine. But the excessive sentimentality with which she is mourned is surely Victorian.

This Issue

October 9, 1997

-

1

Lytton Strachey, Queen Victoria (1921; reprinted Penguin, 1971), p. 84 in Penguin. ↩

-

2

Strachey, Queen Victoria, p. 87. ↩

-

3

Strachey, Queen Victoria, p. 124. ↩

-

4

Elizabeth Longford, Victoria R.I. (Harper, 1964), p. 324. ↩

-

5

Longford, Victoria R.I., p. 325. ↩

-

6

Strachey, Queen Victoria, p. 155. ↩

-

7

Strachey, Queen Victoria, p. 158. ↩