It began over dinner. Abigail Thernstrom, a conservative who argues that America’s race problem has been substantially solved and that measures to deal with it should wind down,1 was dining in April 1993 with a Washington legal activist of similar views, Clint Bolick. “Clint,” Ms. Thernstrom said, “you’re going to love her.”

The “her” was Lani Guinier, professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania, who was said to be President Clinton’s choice for assistant attorney general in charge of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. Ms. Thernstrom was being ironic. She meant that Lani Guinier would make a wonderful target for conservatives, a “very radical” professor whose nomination could be defeated in the Senate.

Mr. Bolick had never heard of Professor Guinier. But as he explained later to Michael Isikoff of The Washington Post, he was looking for a chance to get even with the civil rights and liberal organizations that had nearly defeated the nomination of his mentor and friend, Clarence Thomas, to the Supreme Court. Mr. Bolick had worked for Justice Thomas at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and then for William Bradford Reynolds, President Reagan’s far-right assistant attorney general for civil rights.

Professor Guinier was nominated on April 29. The next day Mr. Bolick had a piece on the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal. It was a devastating attack on Ms. Guinier and on Norma Cantu, nominated to be assistant secretary for civil rights in the Department of Education.2

“Clinton’s Quota Queens,” the headline said. It could have been the work of the savagely effective headline-writers at The Sun, Rupert Murdoch’s British tabloid. The label “quota queen” stuck to Professor Guinier, although the facts belied the implication that she was a great advocate of racial quotas.

The Bolick article’s main attack was on ideas put forward by Professor Guinier, in law review articles, to make the right to vote more meaningful for historically disadvantaged groups: “discrete and insular minorities,” as Justice Harlan F. Stone famously called them. Mr. Bolick quoted passages in which she suggested dropping the “‘winner-take-all’ features of any majoritarian electoral or legislative voting process in which the minority is identifiable, racially homogeneous, insular and permanent.” Instead she proposed a voting system in which “voluntary minority interest constituencies could choose to cumulate their votes to express the intensity of their distinctive groups interests.”

That law-review language, characteristically abstract, dealt with a real problem. Through two thirds of this century, blacks were unable to register or vote in large parts of the South. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, passed by Congress under the pressure of the civil rights movement, finally overcame the devices of trickery and violence that had disenfranchised blacks. But as they became able to vote, they were still largely unable to elect one of their own. The reason lay in the way a voting system based on districts works. Politicians of the majority group can—and in the South did—draw the districts so that in every one the minority is outvoted. In a city that is 20 percent black and has five city council districts, then, five white councilors will be elected.

Congressional districts in the South were one concern as the Department of Justice enforced the 1965 act. Some states with large black populations, like North Carolina, had not elected a black representative since Reconstruction. The Department of Justice’s solution was to require redrawing of a state’s districts so that one or more had a black majority. The result was districts whose odd shapes became notorious. They wound through areas of black population and ended up looking like the salamander-shaped district that gave rise to the word “gerrymander” when Governor Elbridge Gerry presided over the politically inspired legislative districting of Massachusetts in 1812.

The creation of so-called majority-minority districts in the South gave the House of Representatives new black members. But the race-conscious process, and the curiously shaped results, troubled many—including the Supreme Court. It found some of the districts unconstitutional and said that race could not be the dominant consideration in drawing lines. Professor Guinier was highly critical of racially drawn districts, making strong arguments against them in her law review articles. Legislators elected from such districts, she said, would tend to be sensitive mainly to members of their own race—when what the country needs is transracial voting and nonracial solutions to political problems. Ironically, Abigail Thernstrom made exactly the same point in an article criticizing race-based districts.

Professor Guinier’s solution was a form of proportional representation known as cumulative voting, used frequently for the election of corporate boards. It gives each voter as many votes as there are seats to fill, and allows the voter to cast all the votes for one candidate or spread them out as he wishes. For example, in that city with a population 20 percent black and five councilors, each voter would have five votes. He could cast one for each of five council candidates, or he could give a candidate he especially favors more than one vote—up to five. If black voters used all their votes for one black candidate, he would be assured of election. The advantage of the system, Professor Guinier argued, was that all the councilors would have to think about potential votes throughout the city and hence would be sensitive to voters’ needs regardless of race.

Advertisement

A second reform Ms. Guinier proposed was to require supermajorities for action by certain legislative bodies. The familiar example of that requirement in our politics is the United States Senate, where it takes 60 of the 100 votes to end a filibuster, so any controversial legislation requires a three-fifths vote. Professor Guinier argued that, in a situation where white legislators who are a majority habitually ignore the views of their black colleagues, giving the minority a veto by a supermajority requirement would encourage political bargaining to serve mutual interests.

In his Wall Street Journal article, Clint Bolick said Professor Guinier “would graft onto the existing [political] system a complex racial spoils system that would further polarize an already divided nation.” He suggested that her nomination, and Norma Cantu’s, might be “Mr. Clinton’s payback to extreme left-wing elements of the Democratic Party.”

Mr. Bolick set the agenda for the process that eventually killed the Guinier nomination. With a handful of exceptions, the press worked from his premises: that Professor Guinier was a “radical,” that she favored a “racial spoils system,” that she wanted racial quotas. The phrase “quota queen” appeared in Newsweek, The Washington Post, USA Today, and The Chicago Tribune; other papers used the idea without the phrase. Mr. Bolick’s impact on the story did not come only from that first Wall Street Journal piece. He and fellow conservatives turned out what Michael Isikoff of the Post called “a drumbeat of press releases, reports and Op-Ed articles that portrayed [Ms. Guinier] as a pro-quota, left-wing ‘extremist’ bent on undermining democratic principles.” Ms. Thernstrom called her “a black separatist.”

Anyone who actually read Professor Guinier’s writings would have recognized those characterizations for the travesty they were. The main purpose of her work was to bring people together in electoral politics, not to draw racial lines between groups. That is why she was such a strong critic of race-based districting. Voters should be encouraged to join together because they are “of like minds, not like bodies,” she wrote.

Her proposal for a form of proportional representation was directed at situations where history had created rigid racial polarization, so that the dominant majority systematically froze out the minority by political districting and unresponsive representation. And she was not concerned only with blacks in the American South. To the contrary, her voting theory was designed to give a voice to minorities of any color or description in situations of historic racial division. Thus she applied her views to South Africa. In 1992, when South African leaders were negotiating the great change from the all-white politics of apartheid to a non-racial system, she advocated the use of proportional representation. Because whites are a minority just about everywhere in South Africa, they would win few if any seats in an election conducted on a winner-take-all basis in legislative districts. Proportional representation, as she put it, “would enable the white minority to have some representation in the legislature.” The constitutional negotiators agreed on just such a system, and in the 1994 election the largely white National Party won 20.39 percent of the votes and 20.5 percent of the seats.

“In the end,” Professor Guinier wrote in 1992, “democracy is not about… arbitrarily separating groups to create separate majorities in order to increase their share.” She urged “cross-racial coalitions” that would “reduce racial polarization.”

Moreover, the remedies that she proposed had already been adopted in a number of places in the South, and had been approved by the Justice Department in previous administrations and by the courts. A notable example was the adoption of cumulative voting in Chilton County, Alabama, south of Birmingham. When a lawsuit was brought there in the 1980s, its population, according to Guinier, was 11 percent black but it had never had a black member of the county commission or school board. In 1988, in cumulative voting, a black man, Bobby Agee, was elected to the seven-member commission. Three Republicans were elected, too: a change. A few years later Bobby Agee became commission chairman, and white and black officials said the system worked well.

As for the idea of requiring supermajorities for some actions by political bodies, that plan had been approved in Mobile, Alabama. It was proposed by Professor Guinier not as a general change but rather as a remedy for extreme cases, such as white legislators turning their backs when a black member entered the room. When white councilors in Etowah County, Alabama, changed the rules to deprive a new black member of the seat’s traditional power, the Bush administration challenged the action as a violation of the Voting Rights Act; but in 1992 the Court, by a vote of 5 to 4, held that the act did not extend to post-election racism.

Advertisement

The ordinary reader of the press or viewer of television would not have recognized the real Lani Guinier, in view of the caricatures presented during the nomination fight. A Philadelphia Inquirer editor wrote of her as a “madwoman” with “cockamamie ideas.” In U.S. News and World Report she was someone with a “strange name, strange hair, strange ideas.” Misrepresentation spread from one publica-tion to another. A Wall Street Journal columnist, Paul Gigot, jumped on the Bolick bandwagon with a column saying: “So even Virginia’s African-American governor, Douglas Wilder, isn’t ‘authentic,’ she says, because he was elected with votes of the white majority. He must therefore pursue a mainstream agenda that isn’t ‘important to the black community.”‘

That statement was a misleading reference to a footnote in a Michigan Law Review article by Professor Guinier. One section of the article discussed the view that some elected politicians, black or white, are “authentic” representatives of black voters. The only reference to Governor Wilder was in note 151. It mentioned abortion as a possible factor in his election victory. Then it said, “In either case, given the narrow majority, Wilder’s ability to govern on other issues important to the black community is considerably vitiated.” The note did not say that Wilder was not “authentic.” That was made up either by Gigot or, more likely, by an anti-Guinier source who fed him the idea. An editorial in The New York Times repeated the error, saying that Professor Guinier had questioned whether Wilder was “an ‘authentic’ figure for blacks—because he owes his job to white voters as well.”

Professor Guinier made a number of comments in her law review articles that I think were wrong or silly. For example, she suggested that to encourage diversity in appointments, the Senate Judiciary Committee “should begin evaluating Federal nominations with reference to specific goals for increasing non-white nominees.”

The most detached and best-informed appraisal of Professor Guinier after the defeat of her nomination was made by Professor Randall Kennedy of the Harvard Law School in The American Prospect. He found her too quick to see racism in such decisions as the Supreme Court’s dismissal of the Etowah County lawsuit, and he said she had not sufficiently thought through her electoral ideas. But the portrayal of her as a racial separatist was “false,” Professor Kennedy said. Her purpose has been

to find ways that more fully integrate racial minorities into all of the various organs of American self-government…. Far from abandoning democracy, Guinier maintains that, in all too many circumstances, too few people have too little say about the rules and rulers that govern them.

Professor Kennedy concluded: “While there are grounds for criticizing Guinier’s writings, those articulated by many commentators after her nomination revealed the appallingly low intellectual standards in even the upper reaches of the political and journalistic establishments.”

Yes, the press’s performance was abysmal. To put it politely, too many editors, reporters, and commentators were lazy. They served up, without examination, what had been prepared for them by highly biased sources. But Professor Kennedy’s assessment did not focus sufficiently on those sources. It was their zealotry, their relentlessness, their skill at demonization that destroyed the Guinier nomination.

For the attackers, Lani Guinier was only a means to various ends. The ends were to get even with liberals for their attacks on Robert Bork and, as Clint Bolick candidly said, on Clarence Thomas; to make civil rights enforcement suspect in the country, and to hurt President Clinton. To a substantial degree, those ends were achieved.

What is most impressive about the attackers is the way they changed the subject. They made the issue the person of Lani Guinier and her experimental ideas—or, rather, distorted versions of those ideas gleaned from scattered phrases in her writings. They entirely removed from public discussion the record that made her an obvious candidate for the job of assistant attorney general: her record as a litigator for the Legal Defense Fund. She was experienced and highly successful as a lawyer in civil rights matters, and she had notable bipartisan support in that work.

In 1982 she advised senators, including Robert Dole, on amendments they were proposing to strengthen the Voting Rights Act. In 1984, at trial, she won a case challenging the North Carolina legislative districts under those newly enacted amendments. North Carolina appealed, and the Reagan Justice Department came in on the state’s side. A bipartisan congressional group that included Senator Dole filed a brief opposing the Justice Department’s view, and the Supreme Court upheld Guinier’s trial victory. In 1986, in an appearance at a Legal Defense Fund meeting, Senator Dole said: “I see new friends like…Lani Guinier—people I got to know during the 1982 effort to extend the landmark Voting Rights Act…and who I have been pleased to work with since then.” He added that he had never been “more impressed with my legislative allies.”

But on May 20, 1993, Dole took to the Senate floor to denounce Guinier’s views. “I never thought I would see the day,” he said, “when a nominee for the top civil rights post at Justice would argue, not that quotas go too far, but rather that they don’t go far enough.” He said, “I have never met, nor have I ever spoken to, Ms. Guinier.”

There was a particular irony in Senator Dole’s disavowal of the woman he had praised. For she had fought the Justice Department during the years when William Bradford Reynolds, the assistant attorney general in charge of the civil rights division, reduced civil rights enforcement—and opposed Senator Dole’s 1982 amendments to the law. She had supposed that her nomination hearing would focus on the need for more vigorous enforcement of the law.

But there was no hearing. Indeed, Guinier was not even allowed to make a case for herself outside of the Senate. The White House imposed silence on her as the attacks rose, so she could not answer the most preposterous and deliberately false charges.

Considering the frustration she must have endured in that silence, she is admirably calm as she tells the story of the nomination fight in Lift Every Voice. There is more sadness in it than anger. Most telling is what she says about her friend Bill Clinton.

She got to know Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham at the Yale Law School. They came to her wedding. On the first Saturday night after Clinton’s inauguration, January 23, 1993, she and two women friends gave a dinner party and invited the President and First Lady. They came. And Lani Guinier thought: “In his moment of public triumph, Bill Clinton had simply left his grand House to celebrate in the modest home of an honest-to-goodness black friend. We were impressed. We knew that Bill Clinton was probably the very first President of the United States to have enough black friends to hold a party….”

That was then. Now President Clinton refused even to demand a hearing for his friend. “I realized,” Guinier writes, “that my hearing stood for much more than my fundamental right to speak and define myself…. This was a test of Presidential leadership, a window on the Presidential soul.”

She met President Clinton on the night of June 3. For an hour and a half she urged him to press for a hearing. He spoke of how much political damage the administration would suffer if the nomination fight continued. He never asked her to withdraw. Later that night she watched on television as the President said he had just got around to reading her law review articles and found ideas that were “anti-democratic.” He meant proportional representation, which he said was “very difficult to defend.” (Israel, Ireland, Germany, and many other European countries vote by proportional representation.) The President withdrew her nomination.3

The story of the Guinier nomination is about a number of important things: the vulnerability of our political system today to crude manipulation by ideological zealots, the microscopic attention span of our press, the Senate’s refusal even to hear some controversial nominees. (Bill Weld found out about that, too, after he was nominated as ambassador to Mexico but was denied a hearing.) And of course it was about the weakness of this president’s leadership, his unwillingness to stand up for a nominee even when the Senate was under Democratic control.

Guinier tells the sorry story well, avoiding self-pity. Then, in the latter part of the book, she tries to stake out an upbeat position. She tells tales of how Dr. King and others aroused the conscience of the country and made great gains for racial decency. That can happen again, she says, if we look into our hearts once more and lift every voice.

There are reasons for optimism about America’s record on race. Over the last two generations we have made a dramatic—a revolutionary—change. State-enforced racism is gone. The South is another country. But even Pollyanna would have a hard time taking a cheerful view of the problems that remain: the ghettos of our central cities, the persistent failures of public education, the disproportionate unemployment rate among young black men—and the high rate of their imprisonment. The realities are grim, and there is little sign of the commitment needed to change them.

Nor is it possible to brush away the meaning of what happened to the Guinier nomination. In the vicious atmosphere of our politics today, it is so easy for a determined group in Washington to whip up antagonism with slogans and half-truths. When it is a conservative group, it can count on significant financial support. And the supposed watchdogs of the press give the public no idea of what is happening until it is too late.

Lani Guinier did not get the job or a chance to defend herself. But perhaps President Clinton learned something. Eight months later, in February 1994, the President chose another nominee for the Justice Department vacancy: Deval Patrick, a Boston lawyer who had worked with Lani Guinier at the Legal Defense Fund. Clint Bolick was back in The Wall Street Journal with a piece calling Patrick a “stealth Guinier.” His main example of Patrick’s wrongheadedness was his having been a lawyer for the petitioner in the Supreme Court case of McCleskey v. Kemp. It was a murder case in which the Legal Defense Fund challenged the death sentence of a black Georgia defendant, citing a scholarly study showing that a black person who killed a white in Georgia was twenty-four times as likely to be given the death penalty as a black who killed a black. Patrick, and the defendant, lost by a vote of 5 to 4. So Mr. Bolick was in effect suggesting that a lawyer whose argument won four votes in the Supreme Court was disqualified by that argument from the job of assistant attorney general.

President Clinton presented Deval Patrick at a White House ceremony. As the nominee stepped forward, the President—uncertain whether he should have asked Attorney General Janet Reno to speak first—said, “I don’t know what order he’s in.” “Stick with me,” Patrick said, and the President replied, “That’s the idea.” The audience laughed.

When the press was invited to put questions to Patrick, a reporter said conservatives were already attacking him as a “stealth Guinier” and asked the President how he would “sell this nomination and make sure that your view of his record gets out accurately.” Mr. Clinton replied:

When they say “stealth Guinier,” what they mean is that both these people have distinguished legal careers in trying to enforce the civil rights laws of this country…. The truth is that a lot of these people…never believed in the civil rights laws, they never believed in equal opportunity, they never lifted a finger to give anybody of a minority race a chance in this country. And this time, if they try that, it’s going to be about them, because they won’t be able to say it’s about somebody’s writings about future remedies. If they attack his record, it means just exactly what we’ve suspected all along, they don’t give a riff about civil rights.

Deval Patrick was confirmed.

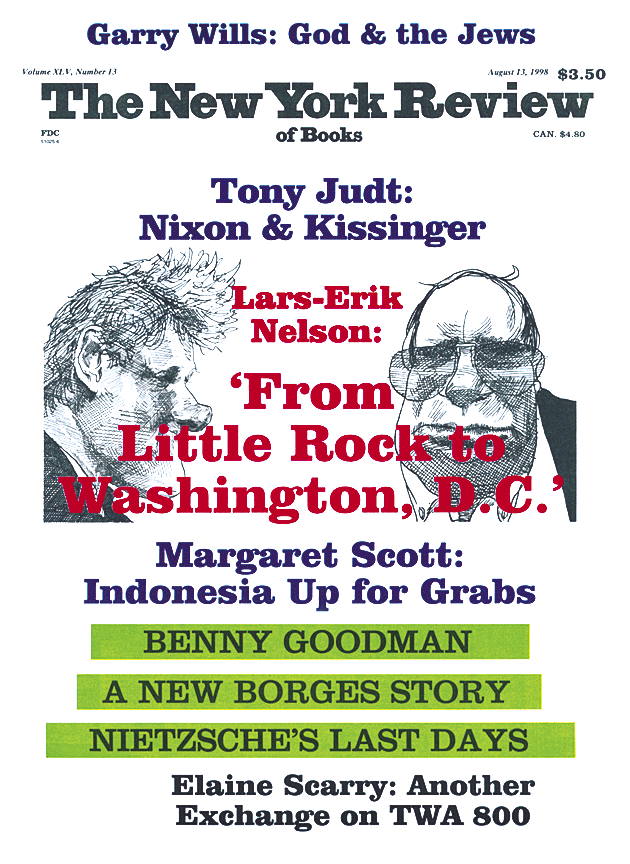

This Issue

August 13, 1998

-

1

Ms. Thernstrom is a relentless opponent of affirmative action. When in 1997 the law schools of the University of Texas and the University of California campuses at Berkeley and Los Angeles reported a sharp drop in minority admissions after they were forced to end affirmative action, even some opponents of the policy were concerned. Ms. Thernstrom commented: “This should be a wake-up call for all schools. These numbers tell us that with affirmative action policies, too many minority students who are not meeting standards are still being admitted.” The Washington Post, May 19, 1997. ↩

-

2

Ms. Cantu was confirmed by the Senate without recorded opposition. ↩

-

3

A New York Times editorial two days later concluded: “If Ms. Guinier’s friendship with Bill and Hillary Clinton at Yale Law School was a major factor in her nomination or vetting, it is time to abandon the buddy system for staffing the Government.” ↩