To the Editors:

I am writing in response to the article “In the Palace of Nightmares” by Mr. Noel Malcolm, published in the November 6, 1997 issue of your journal. Having spent the greater part of my life under a Communist dictatorship, I am very familiar with the Bolshevik mentality according to which an author in general, and an eminent author in particular, is always guilty, and must be punished accordingly. It is well known that in the Communist countries, and especially in my own, Albania, readers were often called upon to demonstrate their vigilance by detecting and denouncing the “errors” of authors. Consequently we writers, who had the misfortune to live in such countries, were under the constant surveillance not only of the State and the secret police but of large numbers of our readers: militant Communists, compositors, jealous colleagues and even foreign “friends,” who zealously denounced our every deviation.

I regret to have to say this, but in Mr. Noel Malcolm’s long article I found precisely this kind of mentality, in other words the desire to wound and a spirit of suspicion, which reminded me of that sad period. It is difficult to quote in a single letter all the inaccuracies, the altered information, the lies and half-lies that pepper this piece, which deceitfully adopts a tone of dispassionate objectivity. At the beginning of his article, Mr. Noel Malcolm presents two opposing judgements which, according to him, are current about myself, one comparing me to Solzhenitsyn and the other to Zhdanov, to which the name of Gorky is added. To this day, I know of no author translated into almost every language in the world who has been compared to a cultural criminal such as Zhdanov, the first official persecutor of authors. Anything can happen in this world, it may be that someone, blinded by hatred, calls another a cannibal, a new Hitler or whatever, but this is not to say that a third party should consider this aberration as a thesis worthy of study. And, apart from Mr. Malcolm, I cannot think that anyone has ever compared me to Zhdanov.

As to the article “Don’t Give the Nobel to an Albanian Party Hack!” which he quotes, it is merely a hateful pamphlet by a certain Stephen Schwartz, who publishes these frenetic and unethical outcries every year as the prize approaches.

Mr. Noel Malcolm pretends to defend me against this grotesque article by Mr. Schwartz, but it is a fake, hypocritical, and insincere defense, which serves only to conceal a future attack. It is like the attitude that one sees when someone accuses an innocent party of killing his own mother and a third party intervenes to refute the accusation, by maintaining that he has committed other crimes but not that one. (For example, he has not killed his mother, but he may have killed his aunt.)

It is a perfidious way of lending credibility to an article.

Mr. Malcolm adopts the attitude of an investigator instituting proceedings against the Albanian author. He checks dates, casts doubt upon a host of questions, worrying, for example, over the fact that the author I. Kadare has not given an explanation of two poems that he wrote in 1953 upon the death of Stalin. Going further, he reminds the author that at the time of the publication of these poems he was not 17, as he has said somewhere, but 18. Then, with apparent magnanimity, he forgives him, asserting that the situation should have no bearing on our appreciation of his work. (In this regard I should like to tell Mr. Malcolm that his generosity is superfluous because, in 1953, at the death of Stalin, and when on this occasion, like thousands of school pupils throughout the Communist world, I wrote those poems, I was actually 17.)

Mr. Malcolm’s long article is peppered with various kinds of false information, serious and not-so-serious. It deliberately mixes the works published under Communism with those that appeared after its fall: nonexistent publications are added, and other actually published are obscured. Taking as his source an insincere malingerer (K. Resuli), who said yesterday that he had been persecuted by the Serbs for being an Albanian, and who today claims to have been a victim of the Albanians on the grounds that he was a Serb, the author of the article suggests that the poem “The Red Pashas” may have existed solely in my imagination. Malcolm even suspects that my house arrest away from the capital was a pure invention on my part. (Everyone knows that in a small country like Albania, the expulsion of an author was an event that could not be kept out of the public eye, and that a sanction of this kind would have been witnessed by thousands, many of whom are still alive today.)

Advertisement

On the one hand, Mr. Malcolm seeks explanations of details, and on the other he is irritated to see the author, like many others, giving explanations or answers—specifically in his books—to questions put to him by a French colleague. Mr. Malcolm writes that Mr. Kadare has now altered the messages that he puts into his books. The claim is utterly false. If my novel The Palace of Dreams has been interpreted as being a work hostile to dictatorship, that meaning has been placed upon it not by me myself but by everyone else, particularly the Albanian Communist State which banned it in 1981, publicly denouncing it as a book filled with “allusions against the regime.” Other novels of mine, such as The Concert, The Monster, Clair de lune, have been banned by order of the state, and I did not invent those orders either.

Mr. Malcolm constructs elaborate theses which then irritate him, and which he ends up by refuting. I have never considered myself either as a hero or as a dissident. In Hoxha’s Albania, as in Stalin’s Russia, a declared dissident was sure to be suppressed. I have always asserted that the best resistance that an author could make to a dictatorship of that kind, in other words to an abnormal situation, was to make “normal” literature. And I think that is what I have done.

In trying to muster arguments against me, Mr. Malcolm mentions my reaction to the émigré author and researcher A. Pipa who, after translating my book Chronicle of the City of Stone, added to it a preface in which he maintained that in it I depicted the Albanian dictator as a murderer and a homosexual, when in fact I had done nothing of the kind. My English publisher thought this interpretation both reprehensible and harmful in that it could, had it been considered accurate, have physically endangered me. I subsequently referred to what A. Pipa had done as the act of a common informer, and rightly so, because an author who lives in conditions of absolute freedom in Washington has no right to cast into the abyss one of his colleagues who is imprisoned within a Communist state. Curiously, Mr. Malcolm is not struck by this cynicism and, remaining true to his idea that the author is always guilty, he devotes all his sympathy to the critic-informer.

In the conclusion to his article, Mr. Malcolm, having praised the novel The Palace of Dreams, strangely turns even that book against me. Should I remind Mr. Malcolm that I am myself the author of that book? Having denounced, as an author, the control and persecution of an entire people, and having done so in 1981, one of the darkest years of the Albanian dictatorship, only to find myself accused of being—once again as a writer—an official within the “Palace of Dreams,” both a warder and a persecutor (no longer an author, but a Zhdanov), I can only explain this situation with reference to brazen cynicism on the part of the accusers….

To conclude, I should like to add that I come from a small country whose culture, after a long period of isolation, is still unknown to the world. This people, which has been seen in the past and is still seen as being entirely without culture, is for the first time acquiring, in an intellectual realm such as literature, an international reputation. Mr. Malcolm’s unjustified irritation, his provocative posture, his excess of zeal in denigrating a representative of this culture, are really quite surprising. I wonder whether Mr. Noel Malcolm would dare to sit in such arrogant judgment over eminent writers from his own country, and whether the author of the pamphlet “Don’t Give the Nobel to an Albanian Party Hack!” would discuss them in such insolent terms. To take such a liberty with a writer just because he happens to come from a small country is to reveal a colonialist mentality. Cultural racism is just as detestable as any other kind.

I have been a keen reader of your journal for many years, dear Editor, and so I would hope that you will publish this letter as soon as possible.

Ismail Kadare

Paris, France

Noel Malcolm replies:

The degree of misunderstanding, misrepresentation, and misdirected hostility here is truly breathtaking. My review was not an attack on Mr. Kadare, and it was certainly not animated by a “desire to wound,” or a “Bolshevik mentality,” or “cultural racism,” or any of the other bizarre motives he attributes to me. What I wrote was fundamentality favorable to Mr. Kadare, expressing my high opinion of his literary achievements, and arguing against those hostile critics (such as Mr. Schwartz) who have attacked him on political grounds.

Mr. Kadare’s method of interpretation baffles me. He apparently thinks that when I mention criticisms of him by other people, I am ipso facto agreeing with those critics; when I go on to say that I disagree with the criticisms I have cited, he thinks this must be a “fake, hypocritical” maneuver on my part. If that is how texts are to be read, then I fear that sensible discussion of any controverted issue will become impossible.

Advertisement

I repeatedly stated my disagreement with Mr. Schwartz’s polemic (not a pamphlet, but an article in The Weekly Standard), describing its argument at one point as “absurd”; yet Mr. Kadare thinks my views are indistinguishable from Mr. Schwartz’s. When I mentioned Arshi Pipa’s interpretation of the novel Chronicle in Stone, I described it as “very unconvincing”; yet Mr. Kadare thinks I cited it only in order to defend Professor Pipa. When I referred to Kapllan Resuli’s claim about the nonexistence of the poem “The Red Pashas,” I did not say that I agreed with it, and merely offered it to the reader as a sign of the controversy and obscurity that surround this work; yet Mr. Kadare says that I presented it as my own suggestion, using Resuli as a “source.”

At the beginning of my review, when I mentioned the comparison to Gorky and Zhdanov, I made it entirely clear that this was not my own opinion but that of Mr. Kadare’s “enemies”; yet Mr. Kadare somehow imagines that I am myself accusing him of being a “Zhdanov.” “Apart from Mr. Malcolm,” he writes, “I cannot think that anyone has ever compared me to Zhdanov.” I have to tell Mr. Kadare that if he opens the book I referred to by Kapllan Resuli (with whose many attacks on him he is, I am sure, perfectly familiar) at page 16, he will find the following sentence: “If Enver Hoxha was the Stalin of Albania, Ismail Kadare was the Zhdanov of Albanian literature.” Let me just restate the obvious: I was not agreeing with this line of criticism when I cited it, and the whole argument of my review was in fact directed against it.

I fear it would weary your readers if I tried to take up every point on which Mr. Kadare has misunderstood me; but here are the main ones. On the publication of his two poems about Stalin in 1953, when he was seventeen years old, I merely pointed out that he has always omitted to mention this, his first appearance in print (important though it must have been in enabling him to have a whole book of poems published in 1954, when he was eighteen). I noted that he told one interviewer that his book of poems was published when he was seventeen. I suggested that this memory slip arose because he was in fact seventeen when his two Stalin poems were published in 1953. Mr. Kadare has got my argument completely back-to-front here, and his rather ponderously sarcastic attempt to correct me ends up repeating precisely what I wrote.

Nor, in any case, has Mr. Kadare understood the point I was making. This is what I said:

Let us not make too much of this. Those teenage tributes to the great dictator may or may not have been heartfelt, and, even if they were, can hardly be used to “explain” the rest of Kadare’s literary production. It is only the omission of this detail from his memoirs that is telling.

To restate the obvious again: I was not trying to brand him as a Stalinist on the basis of two schoolboy poems, nor was I blaming him for writing them in the first place.

On the question of his removal from Tirana in late 1975 after the suppression of his poem “The Red Pashas,” Mr. Kadare has also misunderstood me. He seems to think that I regard the episode as “pure invention” on his part; I do not. I never denied that he moved out of Tirana, and I myself described the move as “the punishment he received.” All I suggested was that he has given a slightly exaggerated coloring to his account of these events, by claiming that his poem was seriously regarded as a frontal assault on the Communist regime, and by telling interviewers that he was “chased” out of Tirana or “virtually deported.” As Mr. Kadare knows, for seriously regarded “counterrevolutionary activities” the punishment was death or long-term imprisonment; and internal exile under very harsh conditions was a reality for tens of thousands of people, for decades on end. His removal from Tirana was a very mild form of punishment, and was suggested by Mr. Kadare himself at a “self-criticism” session with his colleagues; he returned to Tirana at the end of the year, and throughout the period of his “deportation” he remained a deputy of the People’s Assembly.

Perhaps the strangest of all Mr. Kadare’s misunderstandings is his claim that I “turn” his book The Palace of Dreams “against” him, using it to argue that he was an Albanian Zhdanov. I cannot see how he can read my words in this way, when what I actually wrote was: “No one who reads The Palace of Dreams, one of Kadare’s greatest works, could possibly accept the dismissive judgment of him as a party hack.” Nor can I see how, after reading that, he can ask his bizarre rhetorical question, “Should I remind Mr. Malcolm that I am myself the author of that book?”

Mr. Kadare resents my calling him an “employee” of Hoxha’s Palace of Nightmares (an allusion to the original Albanian title of the book, “The Employee of the Palace of Dreams”), even though the point I made when I used that phrase was that, far from being just a tool of the regime, he retained in his heart “his own complex loyalties to an inner, mythic world.” But the word “employee,” in a broad sense, is plainly and uncontroversially correct. He earned his living as a member of the Union of Writers, which was of course an organ of the state, and eventually he became both a member of the Presidency of the Union, and vice-president of the Democratic Front. Almost everyone in Communist Albania was, by definition, an employee of the state; he was merely one of the more prominent.

On this point, finally, let me try to explain once again to Mr. Kadare the central argument of my review. I was not adopting (nor am I now) the argument of critics such as Mr. Schwartz, who like to list Mr. Kadare’s public appointments, his membership of the Communist Party, his frequent authorized trips abroad, and his various writings in praise of the Party, and who then use this evidence to dismiss his whole oeuvre as the work of a “party hack.” I understand full well that in Communist Albania the only choice was between making some compromises with the regime, and being locked up for the rest of one’s life (or killed). I do not blame Mr. Kadare for the compromises he made, and nowhere in my review did I do so.

The primary question, for me, concerns the literary value of his work. If his novels consisted merely of “socialist realist” propaganda, then my judgment on him would be negative; but, as I emphasized in my article, they do not. “His most vital novels,” I wrote, “took place on a different plane, at once more human and more mythic, from that of any type of ideological art.” Similarly, in his letter Mr. Kadare says that “the best resistance that an author could make to a dictatorship of that kind, in other words to an abnormal situation, was to make ‘normal’ literature. And I think that is what I have done.” On this, the primary point of my article, there is really no difference between us.

Only at a secondary level did I make any criticisms of him, when I suggested that the mistaken way of looking at his writings which tries to fit them into a black-and-white political scheme had begun to influence the author himself. At this secondary level, therefore, I gave some examples of ways in which he appears to have engaged in some retrospective retouching, exaggerating some themes or details of his life and works and minimizing or omitting others. My argument about these retrospective adjustments was not that they showed that Mr. Kadare had some terrible record to conceal, the revelation of which must destroy his literary reputation; rather, it was that the adjustments were unnecessary, because the essential merit of his literary creation (that is, of his best works, several of which I discussed and praised) remained untouched by such political questions.

It saddens me to note that Mr. Kadare views any criticism whatsoever, even at such a secondary level, as an intolerable act of lèse-majesté. And yet, regardless of all the absurd personal abuse heaped on me in his letter, I do admire him as a novelist, and shall continue to say so.

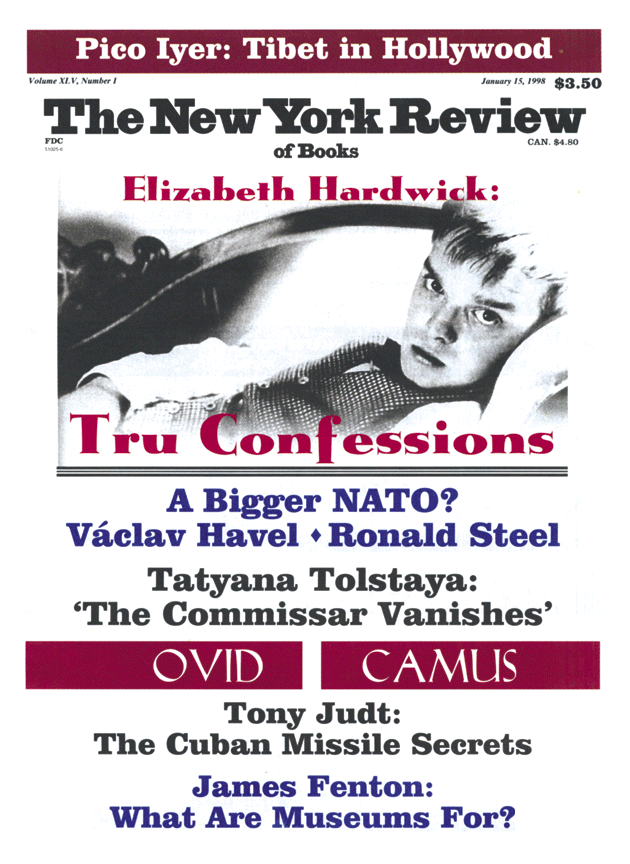

This Issue

January 15, 1998