He marked his epoch. He was a powerful essayist, an author of remarkable plays, and a poet of genius. He created his own language, a language of humble heroism, of self-ironic courage, and of romanticism—the romanticism of a soul that cherishes the classical canon of beauty, the European way of being Polish.

As a poet, he kept telling, with a proud determination, of a conquered and humbled Poland, of her sad dignity in a time when only her dreams had not been humiliated. In his life, he wrote the most magnificent pages in the book of Polish honor.

His language was of transparent beauty, conscious of its own fragility. Yet he was able to link these tender and fragile words in such a way that they became as hard as metal. “Be faithful Go”: this sentence will reverberate in the Polish language forever.

He was formed by an epoch of spiritual confrontation with totalitarian barbarism, which he resisted with exemplary consistency. In the Seventies and Eighties, the poems of Zbigniew Herbert became a prayer of my generation; Mister Cogito became our guide through difficult times in which a monster ruled.

That monster:

is difficult to describe

escapes definitionit is like an immense depression

spread out over the countryit can’t be pierced

with a pen

with an argument

or spearwere it not for its suffocating weight

and the death it sends down

one would think

it is the hallucination

of a sick imaginationbut it exists

for certain it existslike carbon monoxide it fills

houses temples marketspoisons wells

destroys the structures of the mind

covers bread with moldthe proof of the existence of the monster

is its victimsit is not direct proof

but sufficient1

The poet struggled against this monster without pause. In that fight, he could be subtle, but he also could be brutal—striking too hard, or blindly. Always, however, he reached back for the “power of taste,” which forced the poet to rise to the occasion—to look fate squarely in the face.

Now he has been received into the circle of cold skulls—the circle of Gilgamesh, Hector, Roland, defenders of the borderless kingdom and of the city of ashes, into the circle of Kochanowski, Mickiewicz, Slowacki.

Zbigniew Herbert is today mourned by all Poland, by people of all ideological stripes and literary sympathies. When he was pronouncing on social and political matters, he did not depart from the norms of the Polish inferno that has engulfed us in recent years; but when he spoke in verse, he attained the perfection and wisdom of heart that belong only to masterpieces.

There were times when I had the privilege of being close to Zbigniew Herbert. His poems helped me survive the difficult years of prison. This I have never forgotten. Then our ways violently parted. In recent years I was often unable to understand his political statements. But his poems always brought me to enchantment and meditation.

And this is how it will remain:

The ditch where a muddy river flows

I call the Vistula. It is hard to confess:

they have sentenced us to such love

they have pierced us through with such a fatherland2

—Translated from the Polish by Irena Grudzinska Gross

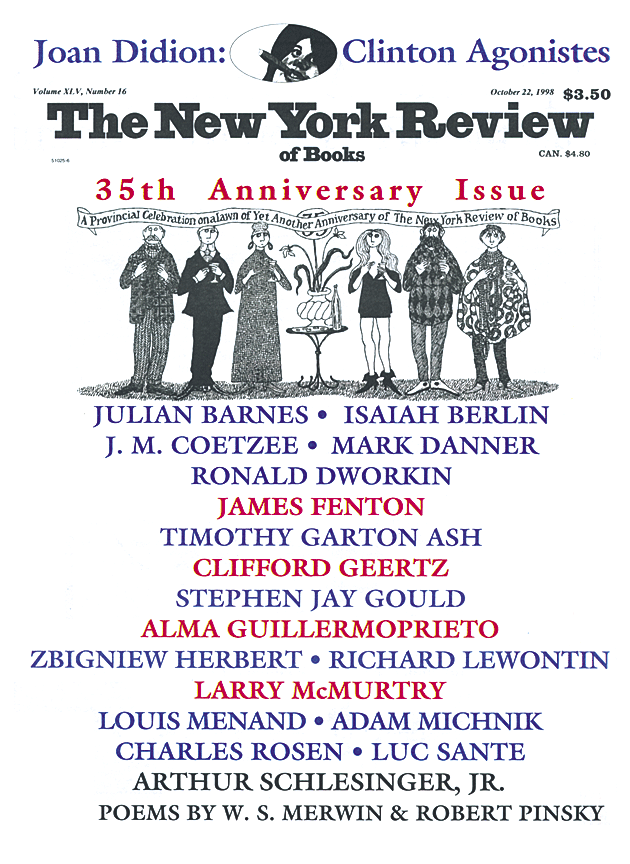

This Issue

October 22, 1998

-

1

Fragment of “The Monster of Mr. Cogito,” from Zbigniew Herbert, Report from the Besieged City and Other Poems, translated by John and Bogdana Carpenter (Ecco Press, 1985). ↩

-

2

Fragment of “Prologue,” translated by John and Bogdana Carpenter, from Zbigniew Herbert, Selected Poems (Oxford University Press, 1977). ↩