The photographs Walker Evans made of the small-town, dirt-farm South in the 1930s for the Resettlement Administration and the Farm Security Administration and for Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), his collaboration with James Agee, are definitive and so characteristic that today it might almost seem as if he not only made the pictures but, like a novelist, invented their subjects as well. Conversely, because the pictures are so rigorously plain, you might think that he just got lucky, happened to be there with a lens and a shutter, as if anybody remotely awake in that place at that time could have done the same. But of course there were other photographers working the same beat then, and their pictures don’t look much like Evans’s. Either they strove for the messages and sentiments and aphorisms that Evans vacuumed from his work, or else they allowed themselves a style. At his peak, Evans possessed a conjurer’s genius, shared with certain character actors and a very small number of writers, for making art that appears neither to be art nor to have been consciously made.

New York City is not the first subject pool that comes to mind with Evans, so that the show organized by the Getty Center, which owns far and away the largest collection of Evans’s work in the world, could superficially pass for one of those thought-provoking sidelights: Degas in New Orleans, Flaubert in Egypt. But Evans lived in New York most of his adult life, began his career there, and consistently returned to it with his camera, and the show turns out to function something like an X-ray of his work’s course. Its four small rooms (the Getty’s buildings, which look like a post-mod set of Delphic temples, dramatically poised on a hilltop overlooking Los Angeles, contain a museum that is, proportionally, itsy-bitsy) correspond to the major periods of Evans’s creative life. The first covers his brief but dashing apprenticeship in the late 1920s, when he was a determined modernist. The second and third are devoted to his peak, the 1930s. The last only contains pictures made in the early 1960s, but it does not misrepresent his last thirty-odd years of work, when he was above all else a collector.

Evans’s background was archetypal Midwestern middle-class. He could append a “III” after his name. He grew up in a Chicago suburb in which all the streets were named after people and places in the novels of Sir Walter Scott. His childhood was Booth Tarkingtonian up to the point when Evans II dumped the family to move in with his favorite widow. He was a largely indifferent student who climbed a rickety ladder of secondary institutions, winding up with a year at Andover, after which he spent a year at Williams College, and that was that. His future career seems nowhere foreshadowed. He actually had vague literary ambitions which culminated in the standard year in Paris. This failed to produce the standard novel, but it did plant something in him: he had a camera and came back with a few striking snapshots. Upon his return in 1927 he made friends with a German boy who had a Leica and they went around photographing New York City.

Evans’s pictures were serious right away. He had absorbed European modernism, and 1927 was a good year to apply it in New York—the skyscraper boom was on. Had he fallen off a parapet in 1928 he would hardly be a household name, but he would still rate mention in large histories of American photography. Although his pictures of construction sites and midtown canyons and high-rise clusters may not be the last word in originality, they are strong and jazzy, full of tough geometry and self-confident shadows and blanks: Moholy-Nagy or Rodchenko on site could scarcely have done better. He also took dramatic, looming pictures of the Brooklyn Bridge, three of which were used in the first edition of The Bridge by Hart Crane, a friend of his. Few of these photographs of architecture would be immediately identifiable as Evans’s in a blind test, but recognizable elements of his burgeoning style begin showing up remarkably soon.

His lifelong preoccupation with signs, for example, starts poking up as early as 1928. Maybe the words are at first artistically truncated, as in his delicate little cubistic studies of Coney Island, which dance around “Luna Park” and “Nedick’s” without ever rendering either name in full. Before very long, though—and all we can do is conjecture the sequence, since few of the early pictures are reliably dated—he is sufficiently confident, or entranced, to serve up a foursquare image of workmen unloading an enormous sign from a truck; “DAMAGED,” it says. Announcing the second room at the Getty show is the picture called either “Times Square” or “Broadway Composition” (dated 1930 there but 1928- 1929 elsewhere), a darkroom montage of colliding neon words that has to be one of the most self-consciously arty things Evans ever produced, and yet today its artiness itself looks pop; it could easily be a process-shot still from an early Hollywood musical, the blur of signage that dazzles Ruby or Betty as she gets off the bus from Sioux Falls. (See illustration on page 26.) There was something about Evans that could not stay rarefied for long.

Advertisement

By that time he was collecting faces, too, many of them as bluntly frontal as Paul Strand’s 1916 “Blind,” the one picture Evans admired in the entire run of Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work. His earliest iconic image, “6th Avenue” (1929), is a twofer. Stage center is a stout black woman in a cloche and a huge fur collar, taxis rushing by behind her; to the right are the stairs of the El, with “Royal Baking Powder” on the riser of every step. Either just before or just after taking that picture he made a study of the stairs by themselves.

But at the time he was still casting about, trying on different photographic hats, making Umbo-like or Rodchenkoesque perpendicular shots of pedestrians on the street below, middle-period-Paul-Strand domestic interiors in which unassuming lamps or chairs are pinned to the wall with giant shadows by a megawatt flash, Man Rayish double exposures presumably portraying the subconscious of his raffish-looking subject Berenice Abbott. Abbott, of course, had just returned from a sojourn in Paris, bearing with her a great deal of the work of the recently deceased Eugène Atget. Seeing this must have given him a jolt. In Atget, as Belinda Rathbone writes, “all of his latent instincts were combined: a straight cataloguing method imbued with an inscrutable melancholy, a long look at neglected objects, and an unerring eye for the signs of popular culture in transition.”

His chance to take up Atget’s baton came soon. In 1930 Lincoln Kirstein, who had already published some of Evans’s work in Hound and Horn, decided to collaborate with the poet John Wheelwright on a book about American vernacular architecture. Evans was to illustrate it. He was trying out the 8å´10 view camera, having received instruction from the photographer Ralph Steiner (who with his interest in signs and front-porch bric-a-brac and head-on method of portraying them was something of a proto-Evans). The book was never written, but Evans took pictures of Victorian houses grave or preposterous with a directness and a hush often worthy of Atget. Anyway Evans was sure of himself by then, and his interest in decay clashed with Kirstein’s mission; he was concerned neither with nostalgia nor with preservation. In a review in Hound and Horn he had proposed that photography’s task was to catch “swift chance, disarray, wonder.” Even more to the point is what he wrote thirty years later in an unpublished note: “Evans was, and is, interested in what any present time will look like as the past.”

This notion, maybe not so precisely articulated, must have been in his head by the early 1930s. As of 1932 or so all the derivative strivings are gone from his work, and instead there is an urgent drive to record, combined with an eerie detachment—the eye of the future. He was photographing doorway sleepers, park-bench sitters, truckers, anonymous crowds, torn posters, painted signs on buildings. There is no apparent style by this point, and yet the pictures could be no one else’s. Even a seeming surprise such as the Getty’s disorienting “Street Scene, Brooklyn” (1931)—a shot of a mirror, loaded on a moving truck, backed by a brick wall and chalk-graffitied doors, that reflects a deep-focus jumble of furniture—is finally not uncharacteristic, since it points up the collage sensibility that a few years later would let him see the beauty in West Virginia miners’ shacks decorated with advertising blowups.

Meanwhile, Berenice Abbott was herself walking around New York City under the spell of Atget, photographing newsstands and grocery-store sidewalk displays and buildings plastered with geological strata of torn posters, among other things, but you seldom mistake her work for Evans’s, or vice versa. A key exception on Evans’s side is the Getty’s “Second Avenue Lunch,” also known, tellingly, as “Posed Portraits” (1931): a cook with his arm around the neck of a workman—a rare instance in which Evans lets the subjects control the emotional temperature of the scene, something Abbott allowed as a matter of course. Broadly speaking, Abbott’s pictures are three-dimensional—her newsstands and fruit stands have an illusionistic power that makes you want to reach in and pick something up—whereas Evans’s are most often flat, nailed to the picture plane somehow even when the subject is presented in three-quarter view. Evans, determined to strip his pictures of affect, could turn his subjects into specimens, his street scenes into friezes, his portraits into “Wanted” posters. He could be dispassionate to the point of cruelty, which is one reason his portraits from this period on can be so affecting: their subjects’ emotional projection feels unusually hard-won.

Advertisement

In 1933 Evans went to Cuba to take pictures for a political exposé of the Cuban government. He followed his own inclinations, aesthetic to the detriment of outrage. Not that this made his pictures appear superficial or disdainful or dandyish—his eye sought the elite, but he found its membership everywhere. He wasn’t interested in just any crude handmade signs, for example, only the ones with style, whether or not it was intentional. His people are never grotesques—his cops and landlords have a certain flair about them, and his peons and beggars and idlers are seldom less than beautiful. The studies he made of grime-encrusted Cuban dockworkers have an impossible panache; each is wearing a different hat, and each one wears it definitively. In the Cuban portfolio can be seen a précis for the work he was to do a few years later for the FSA. The themes are all struck one after the other: the elegant bystanders, the streetside loungers, the uncertain crowds, the ironically garish movie posters, the ad hoc enterprises, the accommodations of architecture, the poetry of display. As a bonus, he threw into the package pictures, of riots and confrontations and corpses, that he found in local newspaper files. Except that he seldom if ever photographed action, nearly any of them could be his work, not that he was trying to fool anyone. The desire to possess was never far from the surface with Evans, and you get the feeling he rarely photographed anything he wouldn’t have been happy to have made himself.

Beginning in 1935, hired by Roy Stryker at the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration) with a shifting mandate to document misery, its engineered relief, and ultimately the sundry details of daily life as he found them, he worked his way down through Pennsylvania and West Virginia, eventually to Mississippi and Alabama and the Carolinas. As a government employee he was difficult, demanding, headstrong, arrogant, uncommunicative, late, and sometimes extravagant; he also made many of his most famous, most lapidary pictures. He photographed the things he was interested in and pretty much ignored orders, direct or otherwise. He was not about to produce propaganda; for that, Stryker could call upon Arthur Rothstein, Russell Lee, Marion Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, the brilliant and very committed Dorothea Lange, or Evans’s old friend Ben Shahn, who likewise saw himself as working on the front line. For that matter, Life had the shameless Margaret Bourke-White. James Agee neatly tacked her up in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by merely reprinting, verbatim, a profile from the New York Post (“a liberal newspaper”):

“One photograph might lie, but a group of pictures can’t. I could have taken one picture of share-croppers, for example, showing them toasting their toes and playing their banjos and being pretty happy. In a group of pictures, however, you would have seen the cracks on the wall and the expressions on their faces.”…Sometimes, she explained, when she knows that the light will be right only a few hours of the day for whatever pictures she is taking, she has her horse brought around to “location” and rides until the light is right….

Evans took pictures of factory towns, car dumps, antebellum mansions, Civil War memorials, movie theaters, soil erosion, store interiors, gas stations, shanty towns, Negro churches, billboards, photographers’ window displays, minstrel show posters, flood victims. He also took pictures of the Tengle, Fields, and Burroughs families, tenant farmers and half-croppers in Hale County, Alabama, for a joint project with James Agee that was to be called “Three Tenant Families” and published by Agee’s employer, Fortune, ending up as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

The two spent part of the summer of 1936 with the three families, Agee actually living in the Burroughs cabin and writing by lantern light on the porch, Evans repairing to a hotel at night. The article stretched and then burst its bounds, and was predictably turned down by Fortune. Agee’s text is tortured, biblical, self-recriminating, exhaustive, exhausting, and (some still disagree) magnificent. He systematically picks through every conceivable accessible aspect of the families’ lives, and ceaselessly worries his relationship to them, all the while explaining that the book is a mere preface to a larger treatment. Along the way he makes an inventory of every single object in the Burroughs house, in effect writing a parallel to Evans’s photographs, bothering to, say, take down the exact content of stray bits of newspaper:

NEW STRIKE MOVE

EARED AS PEACE

NFAB SPLITSUP

Evans’s photographs, of course, possess the immediate advantage of letting you see, for example, all four calendars in the Tengle parlor at once, along with the multiple copies of holy pictures and the dime-store die-cuts and the cover of Progressive Farmer that also adorn the wall, and the ink and patent-medicine bottles, the scarred mantelpiece, the mottled wall itself. But the two parts of the book (Evans’s portfolio, which precedes the title page, was cut down to thirty-one pictures in the original 1941 edition, the full sixty-two restored in the second edition, in 1960) do function as partners to Agee’s text. Agee supplies the dimension of time, for one thing, not to mention moral debate, and each man seems to have pushed the other past his normal limits. In Evans’s case that includes an intimacy with his human subjects he seldom attained, or sought, before or after. The book sold some 600 copies its first year and was thereafter remaindered for as little as nineteen cents a copy.

But Evans was then just past the summit of his career. In 1938 the Museum of Modern Art, which had given him his first one-man show, of Victorian architecture, in 1933, allowed him free rein with the dauntingly titled American Photographs. The catalog, which has been reprinted numerous times, is an established classic. Gilles Mora and John T. Mill perform a signal service in The Hungry Eye by reconstructing the sequence of the show, which included one hundred pictures, rehung by Evans on the eve of the opening (he recropped many of them, glued all of them to cardboard, and sometimes glued that directly to the wall). The pictures in the catalog function in time, one after another with a blank page facing each. In the show they are allowed to sweep across space in a breathtaking continuous reel. They are organized entirely by affinity, chronology and conventional logic overridden, each image seeming to suggest the next, Cuba and Connecticut and Alabama and New York City revealing their submerged correspondences. The effect is overwhelming Cinemascope and not too far from Surrealism.

That same year he produced most of the pictures that fill the third room of the Getty show. He painted a camera matte black and put it under his coat, its lens between two buttons, rigged a cable release down his sleeve, and rode the subway, accompanied by the young photographer Helen Levitt, snapping surreptitiously whoever happened to be sitting across the aisle. The result, not published until 1966 (as Many Are Called) because he feared lawsuits from his unknowing subjects, is one of the very greatest representations of New York City. You get the messengers, the housewives, the nuns, the dockwallopers, the wiseguys, the dandies, the domestics, the crooks, the anal retentives, the shopgirls, the immigrants, the sailors, the troglodytes, the common pests—in other words everybody—all of them unposed and unguarded, large as life and twice as natural, in the darkness of the old brown trains with their incandescent lights. (See illustration on page 25.) Each figure is isolated and all of them are linked together, equalized by the circumstances, strangely beautiful in their absorption. A roomful of these pictures feels like eight million.

After that, Evans went to work for Time-Life, initially as a movie and book critic for Time, a wartime fill-in, and later for Fortune, as a photographer with a measure of autonomy. Some of the work he did there was solid—a corrosive photo-essay on Chicago, for example, with its neighborhoods of formerly posh row houses reduced to freestanding ruins, and some pieces on various cities that included stints where he parked himself alongside a building and took pictures of people as they passed, like a street photographer working on spec. But then he went south again in 1948 for an essay on Faulkner’s Mississippi and found himself replowing old ground, minus the passion. He was a professional then, able to take pictures up to the very highest standards of magazine journalism, pictures that could be mistaken for the output of any capable and entrenched employee of the Luce empire. The contents of the Getty’s fourth room convey the drift: an essay on the clothing men wore in and around midtown in 1963, for instance—always sharp, often witty, seldom more than that. A series on Third Avenue is a bit stronger: an ancient rummy stepping very gingerly off the curb, unmoored by the brand new glass-and-steel slabs that surround him.

The one picture in the room that has real fire in it is a shot of some trash in the gutter. Evans photographed garbage sporadically over the last couple of decades of his life, and even hauled it home and posed it—at his death in 1975 a sink was found filled with an arrangement of beer-can pull-tops, their ideal pattern still being mulled over. Garbage was a logical development in Evans’s lineage of subjects, the final filtration of the artifacts of humanity, the bottom layer of ruins. Needless to say, for his purposes it had to be eloquent trash; the crushed box of Indian-brand sunflower seeds perches at an angle on the cobblestones and speaks of the 1960s, just as, in the earliest picture in the Getty show, a field of paper litter guarded by the uniformed backs of band members tells us everything we need to know about the Lindbergh Day parade in 1927. Before he died he also made inroads with color, through the agency of the Polaroid SX-70, and this allowed him to look at ever smaller details of scrawls and stencils, to contemplate the voluptuousness of cheap orange dye and the subtle gradations of rust.

He also, in his last years, began voraciously collecting signs of the sort he once restricted himself to photographing. Sometimes, actually, he would shoot the sign in situ and then pull it off the wall or the post and take it home and mount it. One of his most successful works in this vein was a row of six “No Trespassing” signs, identical but for the fact that each is closer to disintegration than the one before it. You can read into this activity his affinities with Duchamp, with Pop Art, with décollage, with Arte Povera, his forecast of appropriation art, etc., all of which are true to some extent. It also represented another logical culmination for Evans, that of locating, seducing, and possessing all the most beautiful results of collaboration between human improvisation and the agencies of time and weather. His was a connoisseurship so insatiable, so arrogant, so nearly carnal that it seemed to bring its objects of desire into being. As an art poised midway between alchemy and shopping, it is more pertinent than ever.

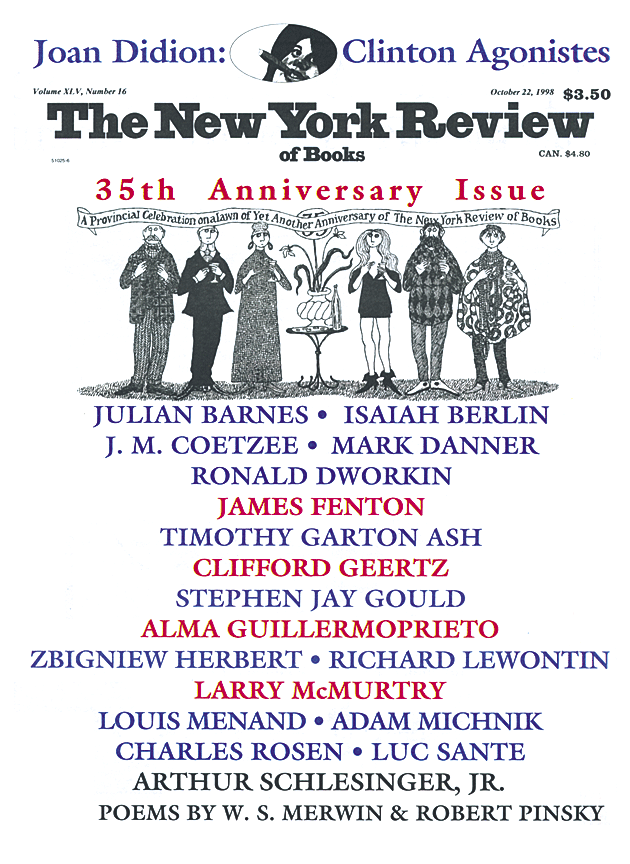

This Issue

October 22, 1998