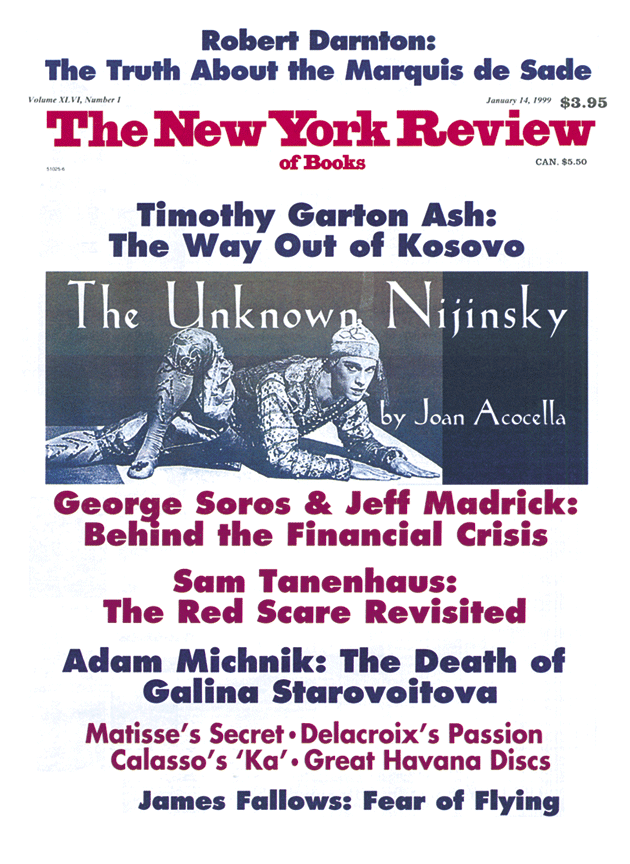

In December 1917, Vaslav Nijinsky, at that time the most celebrated male dancer in the Western world, moved into a villa in St. Moritz with his wife, Romola, and their three-year-old daughter. His relations with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, the company in which he had made his name, were now severed, and with a war on, it was impossible for him to seek other engagements. So he and Romola had decided to retreat to neutral Switzerland and wait for peace. By the time of the armistice, however, Nijinsky had begun to go insane. His famous diary, written in six and a half weeks, from January 19 to March 4, 1919, was the record of his thoughts as that was happening. To my knowledge, it is the only sustained, on-the-spot (not retrospective) written account, by a major artist, of the experience of entering psychosis. Other important artists have gone mad—Hölderlin, Schumann, Nietzsche, Van Gogh, Artaud—but none of them left us a record like this. The diary was first published in 1936, in a drastically expurgated English edition. For over sixty years now, this has been the only available English-language version. In February, at last, a complete English text will be published, in a new translation by Kyril FitzLyon.

1.

Nijinsky was born in Kiev around 1889 to a pair of Polish dancers who worked on the touring circuit—opera houses, summer theaters, circuses—in Poland and Russia. His parents were his first dance teachers. At age seven he made his professional debut in a circus in Vilno, playing a chimney sweep who rescued a piglet, a rabbit, a monkey, and a dog from a burning house and then put out the fire. The following year, the father, Thomas, abandoned the family (his mistress was pregnant), and the mother, Eleanora, moved with her three children to St. Petersburg. At age nine, Nijinsky entered the Imperial Theatrical School, the same school that was to produce Michel Fokine, Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, George Balanchine, and Alexandra Danilova—most of whom, like Nijinsky, began their Western careers with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes—plus, more recently, Rudolf Nureyev, Natalia Makarova, and Mikhail Baryshnikov. He was a poor student (his younger sister, Bronislava, often did his homework), but as soon became clear, he was a phenomenally gifted ballet dancer. By the time he appeared in school productions, the press was already calling him a prodigy, and when he graduated from school in 1907, at age eighteen, he was taken into St. Petersburg’s Imperial Ballet not as a member of the corps de ballet, the usual starting rank, but as a coryphée, one rank higher.

In those days in Russia, as in Western Europe, there was a heavy sexual trade in ballet dancers. Some dancers actually accepted fees from interested ballet patrons for making introductions. In 1907 one such dancer introduced Nijinsky to the thirty-year-old Prince Pavel Lvov, a wealthy sports enthusiast, and Nijinsky entered upon what was probably his first sexual relationship, with the blessing of his mother, who, though she discouraged his heterosexual interests—she felt that marriage would impede his career—was proud to see her son with so fine a figure as Prince Lvov, and was also grateful for Lvov’s financial help. (The Nijinskys had very little money.) But Lvov soon tired of Nijinsky and began introducing him to others, including, in 1908, Sergei Pavlovitch Diaghilev.

Diaghilev, then thirty-five, was one of the most important people in the St. Petersburg art world. With his friends, he was part of the capital’s so-called World of Art group, a loosely organized fraternity of artists, musicians, critics, and other writers who set themselves the goal of liberating Russian artistic culture from the narrow political dictates (realism, nationalism, social criticism) that had dominated it since the 1860s. The group’s most influential project was its journal, Mir iskusstva (The World of Art, 1898-1904), edited by Diaghilev. By publicizing in Russia the avant-garde art of the European fin de siècle, Mir iskusstva was instrumental in converting Russian painting from an exhausted realism to the freer, more imaginative symbolist style of the early twentieth century. Having brought Western art to Russia, Diaghilev then began bringing Russian art to the West, using Paris as his base. There, in 1906, he presented a lavish exhibition of Russian painting and sculpture; in 1907, a series of concerts of Russian music, most of it unknown to Europeans of that period; in 1908, a triumphant production, the first in the West, of Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, starring Feodor Chaliapin.

For 1909 Diaghilev was planning to bring to Paris not just Russian opera but ballet as well. Prince Lvov, Nijinsky writes in his diary, “forced me to be unfaithful to him with Diaghilev because he thought that Diaghilev would be useful to me. I was introduced to Diaghilev by telephone.” He went around to the hotel where Diaghilev was staying, and was bedded, and presumably hired, the same day.

Advertisement

For both men, it was a fateful meeting. Diaghilev’s 1909 Paris ballet season was so successful that he soon established a permanent company. That company, the Ballets Russes, was to be the most glamorous and influential theatrical enterprise in Europe in the 1910s and 1920s, and during its crucial pre-World War I period, Nijinsky’s dancing was a great part of its fame. Conversely, it was the Ballets Russes that made Nijinsky famous. In St. Petersburg he had been a locally celebrated dancer. With the Diaghilev company, in the ballets of the troupe’s house choreographer, Michel Fokine—Les Sylphides, Scheherazade, Le Spectre de la Rose, Petrouchka, others—he became an international star and, by all accounts, a great artist. Apparently, he was an extraordinary actor, not so much realistic as classical, in the Racinian sense. To quote one eyewitness, the ballet historian Cyril Beaumont, “He does not seek to depict the actions and gestures of an isolated type of the character he assumes; rather does he portray the spirit or essence of all types of that character.”1 That he was also a dancer of unprecedented virtuosity is clear from the memoirs of his younger sister, Bronislava Nijinska. Here she is describing his Paris debut, in Fokine’s Le Pavillon d’Armide:

Throwing his body up to a great height for a moment, he leans back, his legs extended, beats an entrechat-sept, and, slowly turning over onto his chest, arches his back and, lowering one leg, holds an arabesque in the air. Smoothly in this pure arabesque, he descends to the ground…. From the depths of the stage with a single leap, assemblé entrechat-dix, he flies towards the first wing.2

The audience gasped, she says, and well they might have, for they had never before seen a male dancer do such things. Though still flourishing in Russia, ballet had been in decline for half a century—and male ballet was all but dead—in Europe. To his Western audiences, Nijinsky was something utterly unforeseen, a miracle.

Augmenting his glamour was the atmosphere of scandal that, wherever he went, his whole life long, was always attached to Nijinsky’s name. In the pre-World War I years, this was probably due to the fact that he lived openly as Diaghilev’s lover—they shared hotel suites—and that the roles Fokine created for him were often ambisexual, and strongly sexual. The best example is the Golden Slave in Scheherazade, where he appeared in brown body paint, and grinning, and wound with pearls—not so much a sex object as sex itself, with all the accoutrements of perversity that the fin-de-siècle imagination could supply: exoticism, androgyny, enslavement, violence. Offstage too, Nijinsky looked exotic. He had a Tartar face, with prominent cheekbones and slanted eyes. (At school, he was known as the “little Japanese.”) Finally, there was his personality. So present and forceful on stage, he was the opposite offstage: naive, shy, recessive—blank, almost. Anything could be projected onto him, and anything was. In her memoirs the Bloomsbury hostess Ottoline Morrell, one of the Ballets Russes’ English patrons, recalled that Nijinsky was the subject of “fantastic fables”—“that he was very debauched, that he had girdles of emeralds and diamonds given him by an Indian prince.”3 During performances, people snuck into his dressing room and stole his underwear.

The note of scandal became more pronounced when, with Diaghilev’s encouragement, Nijinsky began his choreographic career. Between 1912 and 1913 he produced three ballets—The Afternoon of a Faun, Jeux, and The Rite of Spring (to Stravinsky’s now-famous score)—that were like nothing that had ever been called ballet before. The lovely, noble, three-dimensional shapes of the academic ballet, the five positions of the legs and arms, the turned-out feet: all were gone. Under Nijinsky’s direction, the dancers moved in profile, slicing the air like blades (The Afternoon of a Faun), or they hunched over, hammering their feet into the floorboards (The Rite of Spring). The approach was analytic, the look “ugly,” the emotions discomforting. Of these works, only one, The Afternoon of a Faun, survives today,4 but it is enough to show that Nijinsky ushered ballet into modernism. At the time when they were first performed, however, the crucial point about these ballets was that they caused an uproar. The Rite of Spring, as is well known, set off a riot in the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris. The police had to be called. All this added to Nijinsky’s notoriety.

2.

Nijinsky may have been unstable from his youth. His older brother, Stassik, was mentally unsound and had to be hospitalized as a teenager. If, as Bronislava Nijinska suggests, Stassik’s troubles began when he fell out of a window onto his head as a child, his condition would have had little to do with Nijinsky’s. But there were other circumstances. Peter Ostwald, in his 1991 psychiatric biography, Vaslav Nijinsky, speculates that the dancer may have had a genetic predisposition to depression, through his mother. (Her mother, upon being widowed, had starved herself to death.) Ostwald also raises the possibility that Nijinsky may have suffered brain damage as a result of a serious fall that he took at age twelve.

Advertisement

In any case, it is clear that at least by late adolescence Nijinsky was not like other boys. At eighteen, during his first season in the Imperial Ballet, he stopped dancing one night in the middle of the Act I pas de trois of Swan Lake and began taking his bows while the orchestra was still playing. If he was unbalanced at this point, the fame that now began gathering around his name may have unsettled him further. And if he was able to manage celebrity at that time, what was the effect on this quiet boy when, two years later, upon his debut with the Ballets Russes, the Parisians began referring to him as le dieu de la danse? Theater artists must always have some difficulty factoring into their minds the fantasies that they excite in the audience, but in Nijinsky’s case the fantasies were more elaborate and the mind more vulnerable. It is not impossible that his idea, endlessly reiterated in the diary, that he was God began with the experience of being called a god by the Parisian audiences.

To most people who knew him as an adult, the oddest thing about Nijinsky was his social incompetence. The dancer Lydia Sokolova, who began working with him in 1913, says that “when addressed, he turned his head furtively, looking as if he might suddenly butt you in the stomach…. He hardly spoke to anyone, and seemed to exist on a different plane.”5 Sokolova’s statement, together with all other descriptions of Nijinsky written after he went mad, must be understood as colored by that fact. Still, by most accounts, he was remarkably introverted. At parties he would sit silently and pick his cuticles. Even his wife, so protective of his reputation, reports that the dancers called him “Dumb-bell” behind his back.

These social difficulties made his choreographic career a nightmare at many points. The Ballets Russes dancers had been trained in the academic style. To induce them to forget all that and move like figures in an antique frieze or aborigines around a campfire required tact, patience, and excellent communication skills: precisely what Nijinsky lacked. Sokolova recalls that when, in rehearsing Faun, he told her to move through rather than to the music, she burst into tears and ran out of the theater. Others stayed but loathed his work and let him know it. Faun, an eleven-minute ballet, is said to have required over a hundred hours of rehearsal. And Nijinsky had to deal with opposition not just from the dancers but also from his collaborators—Debussy, the composer for Faun and Jeux, disliked both ballets and said so—not to speak of critics and audiences. During the première of The Rite of Spring the uproar in the theater was so great that the dancers could not hear the music. Nijinsky stood in the wings, sweat coursing down his face, screaming the musical counts to the performers—a terrible image.

At the same time, his relationship with Diaghilev was deteriorating. By the time of The Rite of Spring, their love life was apparently over. Worse, Diaghilev seemed to be abandoning Nijinsky as an artist. The company’s next major ballet, The Legend of Joseph, with music by Richard Strauss, was to have been choreographed by Nijinsky. Diaghilev, perhaps dismayed by the scandal over The Rite of Spring—or, more probably, concerned over the strain that Nijinsky’s ballets imposed on the company—now reassigned The Legend of Joseph to Fokine, Nijinsky’s rival, who was also demanding to dance Nijinsky’s major roles. “Perhaps he [Nijinsky] should simply leave the Ballets Russes and not dance for a year,” Diaghilev blandly suggested to Bronislava Nijinska, who was delegated to carry such messages to her brother. Nijinska recalls that Nijinsky was now in a “heightened state of nervousness…, as if he felt that a net was being woven around him.”6

These last events help to explain the extraordinary thing Nijinsky did next. He got married. In the summer of 1913, shortly after the première of The Rite of Spring, the Ballets Russes embarked on a tour of South America. Diaghilev did not accompany them, but someone else did: Romola de Pulszky (1891-1978), a wealthy, headstrong Hungarian, twenty-two years old, the daughter of Hungary’s foremost classical actress, Emilia Márkus. Romola had seen Nijinsky dance in 1912. She thereupon decided to marry him and attached herself to the company, as a sort of groupie, for that purpose. On the ship, she made her interest in Nijinsky known, and two weeks out of port, without having exchanged more than a few words with her (at that time they had no language in common), he proposed. They were married in Buenos Aires two weeks later.

That was the beginning of a series of crises that culminated five years later in Nijinsky’s madness. First, Diaghilev fired him. This is understandable; whatever the state of their relationship, Diaghilev still considered Nijinsky his companion, and he was undone by the younger man’s defection. (Diaghilev’s friend Misia Edwards—later Misia Sert—was with Diaghilev when he received the news. He was “overcome with a sort of hysteria,…sobbing and shouting,” she later wrote.7 ) Nijinsky, on the other hand, was apparently mystified by Diaghilev’s reaction. He wrote Stravinsky begging him to “please ask Serge what is the matter.” “If it is true that Serge does not want to work with me,” he added, “then I have lost everything.” Stravinsky later described this letter as “a document of such astounding innocence—if Nijinsky hadn’t written it, I think only a character in Dostoievsky might have.”8

Nevertheless, Nijinsky’s assessment of the situation was correct: he had lost everything. In order to dance, he did not need the Ballets Russes. Any opera house director would have been delighted to engage this great star to dance the standard ballet repertory. But Nijinsky by this time was not a dancer of standard repertory. He had been through that stage with the Imperial Ballet. He was different now—an experimental artist. He needed roles that would extend his gifts, and above all, he needed to choreograph. For these things he did need the Ballets Russes, which at that time was the only forward-thinking ballet company in the world. While Nijinsky’s later psychosis was probably, in part, biologically based, even the firmest adherents of the biological theory of schizophrenia agree that constitutional vulnerability must be combined with some potent psychological stress in order for the illness to develop. In Nijinsky’s case, the major stress was unquestionably his inability, after his dismissal from the Ballets Russes, to do what he regarded as his work.

Nor, with his personality, could he manage a company of his own, as he soon learned. The following March, with the help of the loyal Bronislava, Nijinsky undertook to mount a ballet season, with a company of seventeen, at a music hall in London, but he fell ill from overwork, and what was to have been a two-month engagement was canceled after two weeks—a humiliating and expensive failure. Ostwald believes that at this point Nijinsky suffered his first “nervous breakdown.” He couldn’t sleep, was plagued by fears, went into screaming rages—a condition that was probably made worse by an increase in his responsibilities: the Nijinskys’ first daughter, Kyra, was born in June 1914. Soon afterward, the family traveled to Budapest, to visit Romola’s mother, at which point World War I broke out and the Hungarian authorities declared Nijinsky a prisoner of war, placing him under virtual house arrest in the home of Emilia Márkus. There he remained for a year and a half—never dancing, trying to devise a system of dance notation, reporting to police headquarters once a week—while Romola quarreled with her mother. Emilia Márkus was a temperamental woman, and she did not relish the prospect of having house guests for the duration of the war.

In 1916 Nijinsky was released, thanks to Diaghilev, who now needed him for a season at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, but the reunion of the two men was poisoned by a quarrel over money. (Romola had decided that Diaghilev owed Nijinsky several years’ worth of unpaid salary. At her behest, Nijinsky had sued Diaghilev in 1914.) When that first American season was over, Otto Kahn, the chairman of the Metropolitan Opera board, engaged the Ballets Russes for a second New York season, to be followed by a cross-country tour (1916-1917), and he unwisely decided that the company should be directed during this period by Nijinsky, not Diaghilev. What followed was probably the most chaotic and demoralized tour the Ballet Russes ever undertook. A four-month journey, stopping in fifty-two cities, with over a hundred dancers and musicians: it was a huge administrative assignment, and Nijinsky had no administrative skills.

By this time, furthermore, he had come under the influence of two members of the company, Dmitri Kostrovsky and Nicholas Zverev, who were followers of the religious philosophy of Leo Tolstoy. Night after night he would remain shut up in his train compartment with these two moujiks, as Romola called them, while Kostrovsky, with shining eyes, called him to the faith. Born a Roman Catholic, Nijinsky had long had a religious turn of mind—Romola records that as a teenager he had dreamed of being a monk—and he had been studying Tolstoy for years. Now he embraced Tolstoy’s teachings with a whole heart. He became a vegetarian; he preached nonviolence; he tried to practice “marital chastity.” He took to wearing peasant shirts and told Romola that he wanted to give up dancing and return to Russia, to plow the land—an announcement that prompted her to abandon him for the last leg of the tour. He tried to run the company in accordance with his new beliefs. For example, he began to practice democratic casting, giving lesser-known dancers leading roles, including his own roles, often without announcing the cast changes to the public.

After this dreadful tour, on which the Metropolitan Opera lost a quarter of a million dollars, Nijinsky performed with the Ballets Russes for a few months more, in Spain and South America, in 1917. By now he was caught up not only in the quarrel between Romola and himself over his Tolstoyanism but also in a struggle between Romola and Diaghilev over what she saw as Diaghilev’s plot to destroy Nijinsky. When the dancer stepped on a rusty nail, when a weight fell from a pulley backstage, these events were not regarded as accidents. In September, the Montevideo newspaper El Día printed what seems to have been Nijinsky’s last interview. “After I left school,” he was quoted as saying, “webs of intrigue were woven around me; people who had no other reason than envy for their hostilities began to appear.”9 Since Romola often distributed typed “interviews” with Nijinsky to journalists, these may be her words rather than his.

On September 30, 1917, after the end of the Ballets Russes’ South American tour, Nijinsky performed with Arthur Rubinstein at a Red Cross benefit in Montevideo. According to Rubinstein’s memoirs, Nijinsky, who was to have been second on the program, delayed and delayed his appearance, while the management threw on hastily assembled acts—the municipal band playing national anthems, a local intellectual declaiming an essay on dance to give him time. Finally, after midnight, Nijinsky came onstage, looking, says Rubinstein, “even sadder than when he danced the death of Petrushka,”10 and performed some steps to Chopin. Rubinstein burst into tears. This was Nijinsky’s last public performance. He was twenty-eight. He then moved with his family to St. Moritz.

According to Romola’s biography Nijinsky, all went well during their first year in Switzerland. Nijinsky, she says, did his exercises every day on the balcony of their house, Villa Guardamunt, just up the hill from the village of St. Moritz. He plotted new ballets, made drawings, and worked on his notation system. Then, around January of 1919, he began to fall apart. He took to closeting himself in his studio all night long, producing drawing after drawing, at furious speed. The drawings were mostly of eyes, Romola reports: “eyes peering from every corner, red and black.” When she asked him what they represented, he replied that they were soldiers’ faces. “It is the war,”11 he said. When he and Romola took walks together, he would stop and fall silent for long periods, refusing to answer her questions. One day he went down to St. Moritz with a large gold cross over his necktie and stopped people on the street, telling them to go to church. He also had spells of violence. He drove his sleigh into oncoming traffic. He threw Romola (holding Kyra) down a flight of stairs.

He also gave a final dance concert, before an invited audience, at a nearby hotel, the Suvretta House. As Romola describes the performance, Nijinsky began by taking a chair, sitting down in front of the audience, and staring at them for what seemed to her like half an hour. Eventually he unrolled two lengths of velvet, one white, one black, to form a cross on the floor. Standing at the head of the cross, he addressed the audience: “Now I will dance you the war…. The war which you did not prevent.” He then launched into a violent solo, presumably improvised, and at some point stopped. On that same day, January 19, 1919, between finishing his lunch and going to Romola’s dressmaker to pick up his costume for the concert, he began his diary.

After the performance at the Suvretta House, says Romola, “I never felt the same again.” Apparently, she had already confided in a doctor, a friend of the family. She does not give his name, but Nijinsky’s diary does. He was Hans Curt Frenkel, a young physician attached to one of St. Moritz’s resort hotels. According to Ostwald, Frenkel’s specialty was sports injuries, but during his medical training in Zurich he had attended lectures by the renowned psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, who in 1911 had invented the term “schizophrenia.” Frenkel was also familiar with Jungian theories of psychopathology. Thinking to help Nijinsky, he began visiting him almost every day. He tried to induce him to reveal his private thoughts; he warned him that his behavior was upsetting Romola. But Nijinsky only got worse. Day after day, he would retreat to his study to make drawings of staring eyes or to write in his diary, which he would not let Frenkel or Romola see. (In any case, it was in Russian, a language that neither of them could read.) Finally, Frenkel wrote to his old professor, Bleuler, asking if he would see Nijinsky. Bleuler agreed. Meanwhile, Romola had apparently summoned her mother and stepfather to come from Budapest and help her take Nijinsky to Zurich. They arrived, and the group—Nijinsky, Romola, Emilia Márkus, and her husband, Oscar Párdány—departed for Zurich. The diary ends on that day, March 4, 1919, as Nijinsky is waiting for the cab to take them to the train station.

In Zurich Romola first went to Bleuler alone. After listening to her account of Nijinsky’s behavior, he told her, “The symptoms you describe in the case of an artist and a Russian do not in themselves prove any mental disturbances.” But the next day, when he saw Nijinsky, he changed his mind. After what Romola says was an interview of ten minutes, Bleuler described Nijinsky in his notes as “a confused schizophrenic with mild manic excitement.”12 The doctor showed Nijinsky out of his office, asked Romola to come in, and told her that her husband was incurably insane. When she returned to the waiting room, the dancer looked up at her and uttered the words now famous in the Nijinsky legend: “Femmka [little wife], you are bringing me my death-warrant.”

Had it been a death warrant, it might have been more merciful. The couple returned to their hotel, and that night Nijinsky locked himself in his room, refusing to come out. After twenty-four hours, the police were called, and they forced open the door. Nijinsky was taken to the Burghölzli University Psychiatric Hospital, where Bleuler was the director. He went without protest. Three days later he was sent to nearby Kreuzlingen, to the Bellevue Sanatorium, a luxurious and humane establishment directed at that time by Ludwig Binswanger, one of the founders of existential therapy. After three months at Bellevue, Nijinsky was hallucinating, tearing his hair out, attacking his attendants, declaring that his limbs belonged to someone else, not him.

It is impossible to know whether this decline was part of the natural course of Nijinsky’s illness or whether it was the result of hospitalization. The hospitalization was clearly traumatic. In his lucid periods, according to the Bellevue records, he would cry out, “Why am I locked up? Why are the windows closed, why am I never left alone?”13 Romola later claimed that Nijinsky’s deterioration was brought on by the episode of the police breaking open his hotel room door and taking him to Burghölzli. She said that her mother had engineered this behind her back. But Nijinsky records at the end of the diary that when they were about to leave for Zurich, Romola came to him and asked him to tell Kyra that he would not be coming back. If that is true, then hospitalizing Nijinsky was part of Romola’s plan for the trip. Nijinsky does not seem to have understood this fully. He took his diary with him on the journey, for, as he says, he intended to find a publisher for it in Zurich. Instead, it was turned over to the doctors of Burghölzli, who copied out passages of it into their records to support their diagnosis.

3.

As I have said, Nijinsky began the diary on the day he was to give the performance at the Suvretta House. This was probably no coincidence. As the early pages of the diary indicate, he already had Frenkel in the house “analyzing” him; it had already been suggested to him that he go see the “nerve specialist” in Zurich. In other words, Nijinsky knew that the people around him had doubts about his sanity, and he must also have known that the performance he was going to give that evening would alarm them further. He may well have embarked on the diary as a last chance to show that he was not mad but, on the contrary, had ascended to a higher plane of understanding. He had joined his soul to God—on the drive to the Suvretta House he told Romola, “This is my marriage with God”—and from God he was bringing a message to the world: that people should not think, but feel. This, he believed, was the source of the tensions between him and Romola. She was trying to understand him through her intellect (“I want to destroy her intellect”), not through feeling. Failure of feeling was also the cause of the war. David Lloyd George, the British prime minister, operated via intellect; Woodrow Wilson (whose pacifism Nijinsky, as a Tolstoyan, naturally supported) relied on feeling, but Lloyd George undermined him.

The war, however, was only one problem. As Nijinsky describes the situation in his diary, the entire world is being laid waste by materialism and opportunism. Scientists are claiming that human beings are descended from apes. Industrialists are despoiling the planet. The stock exchange, the manufacturers, the shops are robbing the poor. This is what he has understood from God. Indeed, he is now God, and he is going to convert the world back to feeling. His primary means will be the diary. Once it is published, he will have it distributed for free. He is hoping to have it reproduced in facsimile rather than printed, because he feels that the manuscript is alive and will transmit feeling directly, off the page, to readers.

He knows that his message will be opposed. In his descriptions of the harm done by the strong to the weak, and by “thinkers” to “feelers,” there are certain names that come up repeatedly, notably those of Lloyd George and Diaghilev: “They are eagles. They prevent small birds from living.” Emilia Márkus is also in this group. But as the diary proceeds, the list of enemies lengthens, for he fears that he will be punished for the truths he is revealing. (He is convinced that Zola was gassed to death for telling the truth in the Dreyfus affair. He also thinks that William Howard Taft has been assassinated.) He is afraid that the English will send people to shoot him because of what he has written about Lloyd George. When he complains about his fountain pen and accuses the manufacturers of fraud, he imagines that they will sue him and have him put in prison. As noted, the drawings that he was making at this time were filled with staring eyes.

There are several other themes in the diary. His bodily processes—eating, digestion, elimination—are on his mind. This is related to his refusal to eat meat, a source of bitter conflict between himself and Romola, probably because to her it symbolized his Tolstoyanism, which, at times, she saw as the source of their troubles. In addition, he is very concerned about sex, which he views with revulsion. (It was partly in order to suppress his sex drive that he refused to eat meat.) He guiltily recalls his childhood sex play and his pursuit of prostitutes before and after his marriage. He imagines that his servants are having sex with animals. He accuses the four-year-old Kyra of masturbating, a practice that he believes causes mental and physical breakdown. (This was a common assumption at the time.) He also meditates on various projects. He wants to build a bridge from Europe to America, presumably to help in uniting the world. He plans to invent a new kind of fountain pen; he will call it “God.” He has a cure for cancer.

One feels a frantic struggle for control underlying much of the diary. In a larger sense, this is Nijinsky’s effort to right the balance of power in the world, to wrest authority from the thinkers, return it to the feelers. At the same time, he is fighting for control over his own life. If he felt that eyes were watching him, they were—Romola’s, Frenkel’s—and he knew where this was leading. Apart from his campaign for feeling, no theme in the diary is more important than his fear of being hospitalized, as his brother was. He mentions this already on the first night of the diary: “I will not be put in a lunatic asylum, because I dance very well and give money to anyone who asks me.” As events gather, he guesses that this is what the trip to Zurich is about.

A little over halfway through the diary, there is a break in the text. Nijinsky signs off—as “God Nijinsky”—on the material he has already written. Then he starts what he calls Book II, entitling it “On Death,” and begins recording terrible thoughts. Suddenly he feels that he is separated from God, and filled with evil: “I am not God, I am not man…. I am a beast and a predator.” He sees ruin closing in on him. “Death came unexpectedly,” Book II begins, “for I wanted it to come.” But it was not death that was coming; it was Emilia Márkus. As he notes, she is arriving at his house the next morning at eleven o’clock. He disliked her already, because of her unkind treatment of his family during their internment in Budapest. But his reaction here is more than dislike; it is a catastrophic fear. He knows that her arrival will be followed by the trip to Zurich—that she has come to help Romola place him in an institution.

Nijinsky’s struggle against the people who think he is going mad would be painful enough, but the situation is worse, for he too knows that he is going mad, or at times he does: “I am standing in front of a precipice into which I may fall.” “My soul is sick…. I am incurable.” Soon, however, he is God again. This is the most wrenching thing about the diary. He knows that something extraordinary is going on in his brain, but he does not know whether this means that he is God or that he is a madman, abandoned by God.

While that drama is taking place in his mind, a parallel drama is going on in the household—what to do with him?—and it is the counterpoint between the two that makes the diary read at times like a novel. Nijinsky’s recording could not be more immediate. At one point, he actually writes while lying in bed with Romola. We get to hear her breathing. As the crisis escalates, we hear phones ringing, people running, Romola weeping somewhere in the house, Dr. Frenkel comforting her. Nijinsky can’t make out what they are saying. He has to guess, and so do we. It’s like a French nouveau roman. Before us we have the man, and in the background, the muffled sounds of his fate being decided.

It is not impossible that Nijinsky was trying to create a work of literature. Each of the three notebooks in which the diary was recorded has an ending that sounds like an ending (even though, in the case of the first two notebooks, the ending was imposed arbitrarily, by the paper running out). The last lines of the first notebook are actually beautiful: “My little girl is singing: Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! I do not understand the meaning of this, but I feel its meaning. She wants to say that everything, Ah! Ah! is not horror but joy.” The last lines of the final notebook are not beautiful, but mordant, ironic: “I will go to my wife’s mother and talk to her because I do not want her to think that I like Oscar more than her. I am checking her feelings. She is not dead yet, because she is envious…” (ellipsis his). Coming at the end of this otherwise passionate and headlong document, such cold words are somehow perfect.

4.

As noted, the diary was first published in 1936, in English. The translation was by Jennifer Mattingly, the editing by Romola Nijinsky. This book, which is still in print—it has become a classic of confessional literature—represents Nijinsky’s text poorly. “In editing this Diary I have kept to the original text,” Romola asserted in her preface.14 Nothing could be further from the truth. To begin with, she extensively rearranged the sequence of the text. For example, she took the beginning of the first notebook and used it to open the final section of her version. (As a result the Suvretta House concert comes after the trip to Zurich.) To make an ending for that final section, she used the conclusion of the first notebook. Then she created an “epilogue” out of some material that she sliced off the front of the third notebook.

The effect of these changes is to obscure the grim march of events—so clear in the original text—carrying Nijinsky from the Suvretta House concert to Dr. Bleuler’s office in Zurich. It is unlikely, however, that Romola was trying to suppress that story. (She told it plainly enough in her first biography of her husband, Nijinsky, published two years before the diary.) Most of her rearrangements seem to be in the service of making the diary more respectable. Nijinsky begins his first entry by saying what he had for lunch, after which he veers off into a description of how the Swiss are as dry as the beans he just ate. To Romola, I believe, this was too humble, and too crazy, a beginning, so she started with a later, nobler passage. Likewise, the materials she moved to the end of her edition—Nijinsky’s description of Kyra singing, his sign-off as “God Nijinsky”—make a nice ending, if not the true ending.

Romola also cut about 40 percent of the diary. For obvious reasons, she deleted all references to defecation and much of the copious material on sex. As for homosexuality, she rewrote Nijinsky’s description of his first encounter with Diaghilev: “I immediately made love to him” became “At once I allowed him to make love to me.” This change, together with her blurring of his references to earlier affairs with men, converted him into an involuntary homosexual. In addition, she dropped a great deal of the domestic material. She disguised identities, more or less eliminating Dr. Frenkel, for example. She also had to deal with a number of uncomplimentary references to herself. Recalling the early days of their marriage, Nijinsky says, “She did not love me much. She felt money and my success. She loved me for my success and the beauty of my body.” Romola translates this as “She loved me. Did she love me for my art and for the beauty of my body?”

Above all, Romola tried to eliminate the less romantic aspects of Nijinsky’s illness: the oddness, the illogic. When he makes bizarre puns, or writes long, repetitious poems full of Russian wordplay, she excises them. When, without transitions, he begins writing now in his own voice, now in the voice of God, she italicizes God’s statements and puts them in quotation marks, thus creating a distinction that Nijinsky did not make. In addition, Romola dropped most of the so-called fourth notebook. Together with the diary, which was written in three school notebooks, Nijinsky left a fourth notebook in which he had written a series of increasingly wild-worded letters to various people. Of the sixteen letters, Romola chose six—the saner ones—and after heavy editing inserted them into the body of the diary. The remaining ten she discarded.

The subtle but wholesale change that Romola wrought can be seen by comparing two versions of a passage in which Nijinsky meditates on the danger he is in. Here, from the new, complete edition, is Kyril FitzLyon’s more or less literal translation of the Russian original:

I know the love of my servants, who do not want to leave my wife by herself. I will not go to my wife, because the doctor does not want it. I will stay here and write. Let them bring me food here. I do not want to eat sitting at a table covered by a tablecloth. I am poor. I have nothing, and I want nothing. I am not weeping as I write these lines, but my feeling weeps. I do not wish my wife ill. I love her more than anyone. I know that if they separate us I will die of hunger. I am weeping…. I cannot restrain my tears, which are dropping on my left hand and on my silk tie, but I do not want to restrain them. I will write a lot because I feel that I am going to be destroyed. I do not want destruction, and therefore I want her love. I do not know what I need, but I want to write. I will go and eat and will eat with appetite, if God wills it. I do not want to eat, because I love him. God wants me to eat. I do not want to upset my servants. If they are upset, I will die of hunger. I love Louise and Maria. Maria gives me food, and Louise serves it. [Ellipsis his.]

The following is Romola’s version:

I understand the love of my people, who do not want to leave my wife alone. I am poor. I have nothing and I want nothing. I am not crying, but have tears in my heart. I do not wish any harm to my wife, I love her more than anyone else, and know that if we parted I would die. I cry…I cannot restrain my tears, and they fall on my left hand and on my silken tie, but I cannot and do not want to hold them back. I feel that I am doomed. I do not want to go under. I do not know what I need, and I dislike to upset my people. If they are upset, I will die. I love Louise and Marie. Marie prepares me food and Louise serves it.

Romola has eliminated two critical elements. One is the connection between love and food. Nijinsky, as he makes clear in the original text, has been called to a meal, so that his grief over his alienation from Romola becomes attached to the idea of not getting food, of starving. Romola probably found this primitive. The other element missing from her version is the layering of events. Nijinsky’s account has three things happening at once. In the dining room are the servants putting out the meal. In another room is Romola, probably weeping again. (Dr. Frenkel may or may not be with her.) In his studio sits Nijinsky, weeping too, and writing and listening. Romola may have felt that this polyphony was confusing or, again, that such details as the goings-on in the dining room were too pedestrian. So she kept only what seemed to her central and noble, Nijinsky’s tears.

Many passages of Nijinsky’s original text are clearly the work of an artist. Some are apocalyptic:

The earth is the head of God. God is fire in the head. I am alive as long as I have a fire in my head. My pulse is an earthquake. I am an earthquake.

Other passages pierce to deep emotional truths. (The paragraphs on his relationship with Diaghilev—his disgust, for example, at the sight of the older man’s pillowcases, blackened with hair dye—are an eloquent statement on the end of a relationship.) Many parts of the text, however, are hard to read: repetitious, obsessional, simultaneously searing and boring, as mad people often are. It was this problem, among others, that Romola set herself to eliminate. By the Thirties, when she began work on her version, Romola made her living (lectures, books, loans, gifts) off the reputation of the genius-madman Nijinsky, who, out of a surcharge of visionary power, had severed his ties with ordinary humanity—“The manifestation of his spirit could only be approached humbly by us human beings,” as she later put it15—but who might someday alight, and dance again. (When the diary was first published, it contained a plea for contributions to the costs of his care.) If the grim details of his illness were to become widely known, this might have made him, and her, a less appealing cause. At the same time, she was trying to protect Nijinsky, and she lived in a time when the preservation of an uplifting legend was more valued than textual integrity.

The original text tells us some new things about Nijinsky, and elsewhere offers new evidence to support old suspicions. First, Nijinsky was not the idiot savant—genius of dance, helpless in all else—that he was often advertised as being. As the diary makes clear, he had read widely in Russian literature—Pushkin, Gogol, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Merezhkovsky—and he thought about what he read, applied it to his own life and work. He knew something about painting, probably because Diaghilev had taken him around the great museums of Europe. He was also up on current events. However mad his lucubrations on the war, they are not uninformed.

Nijinsky says relatively little about his ballets—he doesn’t even mention The Rite of Spring—and most of what he says was included in Romola’s edition. But he tells us other things that, though they were recorded several years after he made his ballets, and in the midst of a psychotic break, nevertheless reflect on his work. In Romola’s version the intensity of his spiritual concerns was already clear; in the uncut version, we see the intensity of his sexual concerns. As Lincoln Kirstein pointed out in his 1970 Movement & Metaphor, the three ballets that Nijinsky created in 1912 and 1913 constitute a sort of ontogeny of sex: “in Faune, adolescent self-discovery and gratification; in Jeux, homosexual discovery of another self or selves; in Le Sacre du Printemps, fertility and renewal of the race.”16 Most of the unproduced ballets that Nijinsky contemplated during his periods of enforced inactivity after 1913 also had to do with sex. One was set in a brothel.

In confronting the abundance of sexual material in the diary, one must make certain subtractions. He was struggling at this time to quell his sex drive, in keeping with Tolstoyan dictates, so sex would have been on his mind. Furthermore, psychotic delusions often involve sexual guilt. Nevertheless, the sexual eruptions in the diary are no doubt an extension of his thoughts as an artist.

One suspicion about Nijinsky that the diary seems to confirm is that despite his early homosexual experience, he was primarily heterosexual by inclination. This point was made by Ostwald in 1991. All the homosexual liaisons that Nijinsky mentions, first with Lvov, then with the men to whom Lvov introduced him, including a Polish count and Diaghilev, were connected with material or professional rewards (though he says he loved Lvov). When he describes sexual experiences in which the motivation is frankly sexual—when he has masturbation fantasies, when he pursues prostitutes before and after his marriage, when he is excited by someone he sees on the street—the object is always a woman. As for his reputed androgyny, again there seems to be a difference between what he did for others and what he did for himself. While Nijinsky made his fame in the androgynous roles choreographed for him by Fokine, the roles he created for himself in his own ballets were unequivocally male. Nevertheless, Nijinsky was clearly interested in exploring the boundary between male and female. He didn’t just dance those sexually ambiguous roles that Fokine made for him; he triumphed in them. Romola, in her Nijinsky, recalls how good he was at impersonating female dancers. “He was able to place himself in the soul of a woman,” she writes.

Another sexual matter on which the diary casts some light is the long-repeated story that while Nijinsky was going insane, Romola was conducting a love affair with Dr. Frenkel. In some versions it is added that Romola’s second daughter, Tamara, born in 1920, was Frenkel’s child. There is no proof of the latter claim. Nijinsky was back at home, on a five-month leave from Bellevue Sanatorium, when Tamara was conceived. And Tamara, in her 1991 memoir Nijinsky and Romola, says that, according to Emilia Márkus, Romola at this time made a determined effort to become pregnant by Nijinsky, in the hope that the birth of another child would jolt him back into sanity. Neither Tamara nor Emilia is a disinterested reporter. Still, the story makes sense. In the diary Nijinsky tells us that Romola wanted to have a son by him.

Nevertheless, Romola apparently did have an affair with Frenkel. Nijinsky at this time was practicing chastity; it is not illogical that Romola would have sought attentions elsewhere. Furthermore, members of Frenkel’s surviving family told Peter Ostwald that such a liaison occurred and that Frenkel, in his unhappiness over Romola’s refusal to divorce Nijinsky, attempted suicide and became addicted to morphine. I too have corresponded with Frenkel’s family, and they have added to this account, as follows. One night in what was probably 1920, a year after Nijinsky was first hospitalized, Frenkel, distraught over his relationship with Romola, closeted himself in a shut-down hotel in St. Moritz and tried to kill himself by means of a drug overdose. His unfortunate wife found him in time to save him. The affair with Romola ended at that point, or before. In an effort to escape the ensuing scandal, Frenkel’s wife changed the family name. Frenkel remained a morphine addict until his death from pneumonia in 1938, at age fifty-one—a sad story.

Ostwald’s hypothesis, however, was not just that the affair occurred, but that Nijinsky suspected it, and that that knowledge was what precipitated the psychiatric emergency which caused him to be taken to Bleuler. This latter part of Ostwald’s argument seems to be contradicted by the diary. In his notebooks Nijinsky gives no sign that he knows of anything improper going on between Romola and Frenkel. Now and then he expresses resentment of Frenkel, but only because the doctor has intruded into the Nijinsky family’s affairs (“I see that doctors meddle in things that are outside their duties”) and because Romola seems to trust Frenkel’s judgment more than her husband’s. (“Dr. Frenkel is not God. I am.”) But the strongest evidence that Nijinsky had no suspicion of an affair between Romola and Frenkel is the tone in which he speaks of her. He sometimes accuses her of terrible things (“You are death”), but he sees her sin as a failure of sympathy, never as betrayal. His attitude is best judged not from his broad statements about her, but from his offhand remarks. He likes her nose; he wants to take walks with her; he calls her by her pet name, Romushka. While he wants to save the world, most of all he wants to save his relationship with her. He also worries about having told her that she was the first woman he ever made love to, when in fact he had had long experience with prostitutes: “If my wife reads all this, she will go mad, for she believes in me.” These are not the words of a man who thinks his wife is having an affair.

A final point that the diary makes clear is that Nijinsky was indeed suffering from what is called schizophrenia. Though schizophrenia, like other psychoses, affects most areas of behavior, it is regarded primarily as a thought disorder. The American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual lists five symptoms: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized language, disorganized or catatonic behavior, and “negative symptoms” (e.g., emotional flatness).17 A patient must have at least two in order to be called schizophrenic. To judge from the diary, Nijinsky had at least three: delusions, disorganized language, and disorganized behavior. Most striking are the delusions. Almost all the varieties of delusion considered typical of schizophrenia are present in the diary: delusions of grandeur, of persecution, of control (one’s actions are being manipulated by an outside force), of reference (environmental events are directed specifically at oneself). Nijinsky also seems to have somatic delusions: he believes that the blood is draining away from his head, that the hairs in his nose are moving around. He may be hallucinating too. Twice he tells us that he feels someone is in his studio, staring at him behind his back. God speaks to him, seemingly out loud.

Even more than their content, however, the form of Nijinsky’s thoughts is characteristically schizophrenic. Some researchers believe that the basic problem in schizophrenia is a breakdown in selective attention, with a consequent “loosening of associations.” The person starts to say something but then makes a peripheral connection, pursues that, and consequently gets off the track repeatedly, issuing long chains of associations. This happens to Nijinsky again and again in the diary. The most striking instance occurs when the dreaded Emilia arrives in St. Moritz. Waking up and hearing her in the house, Nijinsky unleashes a long spiral of associations, starting with Emilia’s voice and veering off onto his nerves, the corns on his feet (he knows how to cure them), the extinction of the earth (he knows how to reverse it), and on and on. One senses his logic: his fear of harm to himself and his insistence that he, not others, not Emilia, has the answer to what is ailing him and the world. Still, it is a dizzying flight.

The diary shows other schizophrenic traits as well—for example, “clanging,” the connecting of words on the basis of sound (often rhyme) rather than sense, and perseveration, or persistent repetition. The repetition also turns up in his drawings of this period. With obsessive consistency, they are composed of circles and arcs. As noted, the arcs seem to form eyes, and Nijinsky says they do: “I often draw one eye.” They also look like the fish, , the sign of Christ. Finally, they also bear some resemblance to the female genitals, the thing that, in his conversion to Tolstoyanism, he had renounced. That may be, at times, the eye that is watching him.

There are factors other than schizophrenia that may have helped to produce the qualities that seem schizophrenic in the diary. Ostwald points out that Dr. Frenkel was giving Nijinsky a sedative, chloral hydrate, that causes attention to wander, and that Frenkel subjected Nijinsky to word-association tests, a possible spur to the bizarre associations we find in the diary. As for repetition, elision, and odd juxtapositions, these were the stock in trade of early modernist artists, of whom Nijinsky was one. (The conductor Igor Markevitch, who at one time was Nijinsky’s son-in-law—he married Kyra—compared the diary’s stream-of-consciousness narration to that of Ulysses.) One must also keep in mind the intellectual trends of the day. Protests against nineteenth-century materialism and positivism, and calls for spiritual renewal, were commonplace. A number of writers of the turn of the century—Vladimir Solovyov, for example—aspired literally to join humankind to the Godhead. Such thinking influenced many artists of the pre-war period, Nijinsky perhaps among them. The particulars of Nijinsky’s life must be taken into account as well. His burning focus on his bodily processes may seem regressive, but for a dancer eating and digestion are professional concerns. Finally, we must grant Nijinsky the privilege of metaphor. If he says that he is God, he also says he is an Indian, and a sea bird, and Zola. And he is not the only one who is God; Dostoevsky is too.

But however much these factors may have affected Nijinsky’s thinking, they cannot have been responsible for the comprehensive derailment that we see in the diary. He himself notices how he gets off the track, and he tries in vain to bring himself back. He is also suffering terribly, and if Romola is telling the truth, he was violent. Her decision to take him to Bleuler was certainly justified. Ostwald points out that Nijinsky met the diagnostic criteria not only for schizophrenia but also for bipolar disorder, or manic-depressive illness. (The manic trend can be seen in the rush of his thoughts, in the forced jocularity of his wordplay, and in his ability to write all night.) In the diary, however, the evidence for schizophrenia appears far more prominent than the signs of manic-depressive illness. Bleuler’s description of Nijinsky—“confused schizophrenic with mild manic excitement”—seems exactly correct.

There remains the question of a connection between Nijinsky’s madness and his art. The idea of the genius-madman is a tiresome one: sentimental, tautological, demeaning to artists. In the case of Nijinsky, in particular, one hesitates to invoke it, for it has been applied to him often, with little gain in understanding. (Indeed, it puts an end to understanding, places him beyond our poor powers.) Nevertheless, many of the characteristics that seem bizarre in his diary—repetition, obsession, “ugliness”—are what seem striking in his art. The quality of abstraction that made his acting so remarkable may have been rooted in the same traits of mind as his communication problems. That is, realistic acting, with its agreed-upon gestures, may have been as unavailable to him as the agreed-upon manners of social intercourse.

Likewise, the experimentalism of his ballets, his analysis of movement, and the fact that he began this analysis in his very first professional ballet, with no preparatory, imitating-his-elders period—in the words of his colleague Marie Rambert, “Everything that he invented was contrary to everything he had learned”18—may have been connected to some neurological idiosyncrasy. Nijinsky’s ballets, wrote Kirstein, demonstrated “theories as profound as had ever been articulated about the classical theatrical dance.”19 Other artists have profound theories too, but to transform them into art, they have to fight their way past formidable barriers: custom, advice, the anxiety to please, the wish to be understood. If, as seems likely, such things were not as real to Nijinsky as to others, he would have been able to go more directly to the bottom of his thought. Why should he worry about being understood? He was seldom understood.

This is not to say that the diary forms part of the same arc of invention as the ballets. In the diary all the things besides profundity that made Nijinsky an artist—shaping, compression, the sense of rhythm and climax, the acts of control—are gone, or going. It is the same instrument, but unstrung.

Nijinsky was almost thirty years old when he was diagnosed as schizophrenic. He lived for thirty years more, during which time his reputation grew. The myth that had collected around him as a dancer—that he was a flame, a vision, a messenger from the beyond—seemed merely confirmed by the news of his illness. It was as if the beyond had reclaimed him. Movies and ballets were based on his story. (The Red Shoes, in some measure, is about him.) He became a symbol for the part of us that, in fantasy, takes off for the high hills, as opposed to the part that stays home. Nijinsky had always been famous for his jump. As witnesses describe it, he would rise and then pause in the air before coming down. Now, it seemed, he had declined to come down.

Such ideas were based almost wholly on his dancing, not on his choreography, which very few people estimated at what seems to have been its true worth until the 1970s, with the publication of Richard Buckle’s biography Nijinsky and, above all, Lincoln Kirstein’s Nijinsky Dancing. (Perhaps not coincidentally, these reevaluations came shortly after Stravinsky, who had long disparaged Nijinsky’s choreography, publicly changed his mind.) Nor could an image of Nijinsky as a mind beyond intelligence have been based on his choreography. While it is possible, as I have said, to relate the experimentalism of his ballets to his later insanity, the first and strongest impression one gets from his one extant ballet, The Afternoon of a Faun, is of a steely intelligence: strict, analytic, even ironic.

While Nijinsky’s romantic image was building, he himself was living a life that could not have been less romantic. From 1919 onward, he was basically a chronic schizophrenic. He was helpless; he could not brush his teeth or tie his shoelaces by himself. When Romola settled in a place where she could keep him, she took him home. The rest of the time he lived in institutions. Usually he was gentle and passive, though occasionally he would throw his food tray at the wall or assault someone. Tamara Nijinsky, in her memoir, recalls watching him one day, at Emilia Márkus’s villa in Budapest, reduce an antique chair to kindling with his bare hands. (It was Emilia’s favorite chair.) For the most part he was mute, but Ostwald’s review of the Bellevue records suggests that Nijinsky could speak when he wanted to: “If someone tried to approach him, he would say, quite coherently, ‘Ne me touchez pas’ (Don’t touch me).”20

On April 8, 1950, during a visit to London with Romola—they were living at that time in Sussex—he died quietly of kidney failure. His death probably aided in the growth of his legend. Before, the press would occasionally publish photographs of this portly, balding older man with the vacant smile. Now, with that distraction eliminated, his story took on new force. The books, the plays, the ballets are still coming. Within the last few years, there have been at least four new one-man shows based on his life. Another movie is in the works.

This, then, is a strange story. Nijinsky has become one of the most famous men of the century, but never was so much artistic fame based on so little artistic evidence: one eleven-minute ballet, Faun, plus some photographs. A large part of his reputation rests on the diary, which, apart from the fact that until re-cently all available versions misrepresented Nijinsky’s text, is not artistic evidence, but something more like a personal letter—“a huge suicide note,” as Thomas Mallon called it21—and one very likely to appeal to our sentimentality about those cut off in the prime of life. By now, Nijinsky is less a man than a saint, his genius less a fact than a tradition. Actually, most great reputations in dance are a mat-ter of belief, for in most cases the dance is gone. But with Nijinsky the belief required is more absolute, in proportion to the claims. Such faith is probably not misplaced, though. On the small artistic evidence that we have—above all, on the evidence of Faun—Nijinsky probably was a genius. Hence the diary becomes a truly terrible document, a record not just of his loss, but of ours.

FROM THE DIARY OF VASLAV NIJINSKY

Diaghilev dyes his hair so as not to be old. Diaghilev’s hair is gray. Diaghilev buys black hair creams and rubs them in. I noticed this cream on Diaghilev’s pillows, which have black pillowcases. I do not like dirty pillowcases and therefore felt disgusted when I saw them. Diaghilev has two false front teeth. I noticed this because when he is nervous he touches them with his tongue. They move, and I can see them. Diaghilev reminds me of a wicked old woman when he moves his two front teeth….

Diaghilev liked to be talked about and therefore wore a monocle in one eye. I asked him why he wore a monocle, for I noticed that he saw well without a monocle. Then Diaghilev told me that one of his eyes saw badly. I realized then that Diaghilev had told me a lie. I felt deeply hurt….

I began to hate him quite openly, and once I pushed him on a street in Paris. I pushed him because I wanted to show him that I was not afraid of him. Diaghilev hit me with his cane because I wanted to leave him. He felt that I wanted to go away, and therefore he ran after me. I half ran, half walked. I was afraid of being noticed. I noticed that people were looking. Ifelt a pain in my leg and pushed Diaghilev. I pushed him only slightly because I felt not anger against Diaghilev but tears. I wept. Diaghilev scolded me. Diaghilev was gnashing his teeth, and I felt sad and dejected. I could no longer control myself and began to walk slowly. Diaghilev too began to walk slowly. We both walked slowly. I do not remember where we were going. I was walking. He was walking. We went, and we arrived. We lived together for a long time…

—Translated from the Russian by Kyril FitzLyon

This Issue

January 14, 1999

-

1

Bookseller at the Ballet: Memoirs 1891 to 1929 (London: Beaumont, 1975), p. 135. ↩

-

2

Bronislava Nijinska: Early Memoirs, translated and edited by Irina Nijinska and Jean Rawlinson (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981), pp. 270-271. ↩

-

3

Memoirs of Lady Ottoline Morrell: A Study in Friendship, 1873-1915, edited by Robert Gathorne-Hardy (Knopf, 1964), p. 215. ↩

-

4

In recent years there have been attempted reconstructions of Nijinsky’s other ballets, but the choreographic evidence is so meager that these productions must be considered constructions rather than reconstructions. ↩

-

5

Dancing for Diaghilev: The Memoirs of Lydia Sokolova, edited by Richard Buckle (London: John Murray, 1960), p. 38. ↩

-

6

Nijinska, Early Memoirs, p. 475. ↩

-

7

Misia Sert, Two or Three Muses (London: Museum Press, 1953), p. 120. ↩

-

8

Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Memories and Commentaries (1960; University of California Press, 1981), pp. 38-39. Quoted in Peter Ostwald, Vaslav Nijinsky: A Leap into Madness (Lyle Stuart/Carol, 1991), pp. 102-103. ↩

-

9

“Nijinski,” El Día, September 13, 1913, p. 8. ↩

-

10

Arthur Rubinstein, My Many Years (Knopf, 1980), p. 16. ↩

-

11

Romola Nijinsky, Nijinsky (1934; Pocket Books, 1972), p. 353. ↩

-

12

Quoted in Ostwald, Vaslav Nijinsky, p. 196. ↩

-

13

Quoted in Ostwald, Vaslav Nijinsky, p. 238. ↩

-

14

The Diary of Vaslav Nijinsky, edited by Romola Nijinsky (1936; University of California Press, 1968), p. xi. ↩

-

15

Romola Nijinsky, The Last Years of Nijinsky (Simon and Schuster, 1952), p. 235. ↩

-

16

Lincoln Kirstein, Movement & Metaphor: Four Centuries of Ballet (Praeger, 1970), p. 199. ↩

-

17

American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), p. 285. ↩

-

18

Interview in John Drummond, Speaking of Diaghilev (London: Faber and Faber, 1997), p. 114. ↩

-

19

Lincoln Kirstein, Dance: A Short History of Classic Theatrical Dancing (Dance Horizons, 1969), p. 283. ↩

-

20

Ostwald, Vaslav Nijinsky, p. 279. ↩

-

21

A Book of One’s Own: People and Their Diaries (Ticknor and Fields, 1984), p. 200. ↩