To the Editors:

Your readers may be interested to learn that four prominent Cuban dissidents have been nominated for the year 2000 Nobel Peace Prize. The four dissidents are: Félix Bonné, an engineering professor; René Gómez, a lawyer; and Marta Beatriz Roque and Vladimiro Roca, economists.

These people were all, at one time, supporters of the Cuban Revolution. Roca, especially, was considered something of a hero by the regime. The son of the late Blas Roca, who co-founded the Cuban Communist Party, Vladimiro Roca was, in the 1960s, a famous young air force pilot; he then served the Party for more than twenty years as a specialist in Cuban-Soviet relations. In 1993, however, Roca privately advocated improvements in human rights and a less-centralized economy. He was summarily fired from his foreign policy job and offered work instead as a gravedigger; his name vanished from the official press, and he became subject to repeated “acts of repudiation,” in which his neighbors were forced to take part in government-organized mob attacks on his family and home.

In 1997, the Castro regime published a paper in Granma, the official Party newspaper, entitled “The Party of Unity, Democracy, and the Human Rights We Defend,” to which the Cuban people were invited to respond. Roca, Bonné, Gómez, and Roque, identifying themselves as the Internal Dissidents’ Working Group for the Analysis of the Cuban Socio-Economic Situation, replied with a paper of their own, “The Homeland Belongs to All.” They called for economic liberalization, freedom of speech, press, and assembly, open dialogue on the country’s future, and legitimate elections.

After they were accused of “counter-revolutionary activities,” their homes were broken into and searched, and the four dissidents were taken to the State Security headquarters at Villa Marista and confined in prison for twenty months before their trial. Last March, during their trial, Granma described them as “nationless,” “annexationist,” and “parasites.” All four are now serving prison sentences for sedition.

Governments such as those of Canada and Spain, which have been relatively friendly to Cuba and which have allowed substantial investment in the island, have expressed strong disapproval of the four dissidents’ treatment.

At the same time, dissent within Cuba seems to be growing—especially among the large Afro-Cuban population, which, despite official antiracist ideology, has suffered disproportionately from the severe deterioration of the Cuban economy over the last decade. This summer, some three hundred dissidents in ten Cuban cities undertook a forty-day fast to demand human rights and the release of political prisoners. (In its 1999 annual report, Amnesty International estimates that Cuba has a total of at least 100 prisoners of conscience, jailed for peaceful expression and association, and at least 250 other political prisoners.) Although the fasting protestors failed to achieve their stated goals, the international attention they received apparently protected them from arrest while they were fasting. At least two of them have since been arrested.

Readers concerned about the dissidents of the Working Group and other prisoners of conscience should write to Ambassador Bruno Rodriguez, Permanent Representative of Cuba at the UN, 315 Lexington Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016, tel. (212) 689-7215; or to Fernando Remirez de Estenoz at the Cuban Interest Section, 2630 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20009, tel. (202) 797-8518.

Barbara E. Joe

Amnesty International USA

Country Specialist for Cuba and the Dominican Republic

Washington, D.C.

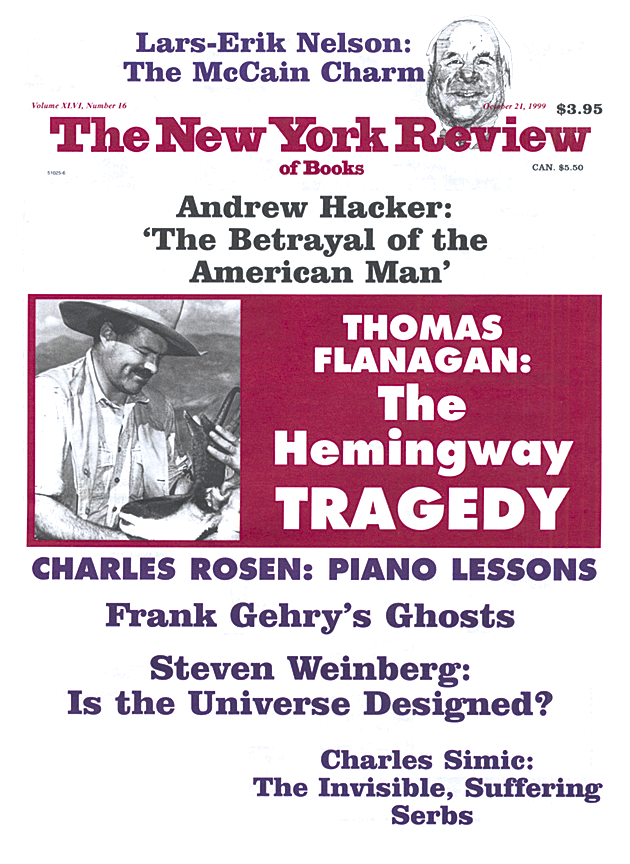

This Issue

October 21, 1999