Pick a horror—perhaps the Bulgarian horror of 1876, which upset Queen Victoria very much, and didn’t help Mr. Gladstone’s lumbago, either. Mr. Gladstone wrote a pamphlet, pointing out that the Turks had done things to the Bulgarians that “might almost make Hell blush.” The Turks, unimpressed, promptly did even worse things to the Armenians. There were more horrors, more pamphlets, including one by the young Arnold Toynbee. All through the twentieth century, as bodies stacked up like posts across the landscapes of Europe, Asia, Africa, earnest commissions trudged off, with cameras and adding machines, to photograph the bodies, count them, compile black books; the commissions are busy still.

We may not know quite the whole story, but we know plenty: what happened to the Polish officers at Katyn, what Hitler did to the Jews, what Stalin did to everybody he could catch, what the Japanese did at Nanking, what—fast-forwarding now—the Khmer Rouge did to the Cambodians, what the Hutus did to the Tutsis, what happened in Bosnia, etc. If we’re schooled at all about our times, we know the bad statistics.

But numbers numb; mass death rarely transmits forcefully to the individual sensibility, unless the individual has actually been to the killing fields and smelled the blood on the ground, or feared to be one of the killed. One horrible death, of the sort shown in the pages of Without Sanctuary, might disturb far more than a big statistic.

Without Sanctuary is the black book of hometown America during the long unchallenged reign of lynch law. It is not encyclopedic: there are only about one hundred photographs of lynchings and the lynched, a small sampling of the kind of things that went on in the 4,742 known lynchings in America between 1882 and 1968. That these were known lynchings—public actions and, in many cases, community actions—is important to emphasize, to distinguish lynchings from the more common but less public forms of racially motivated murder.

The difference might be illustrated by a notorious recent killing, that of James Byrd, a black man, whom three young white men dragged to death behind a pickup, on a rural road in East Texas. It was an exceptionally cruel murder—even a local spokesman for the Klan said that nobody deserves to die that way—but if it had been a lynching, old style, the dragging would have taken place around the public square, after (or before) which James Byrd would have been hanged, burned, castrated, possibly flayed, shot, and dismembered, most of which did happen to a young black man named Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas, May 16, 1916, while an estimated fifteen thousand people watched. Here’s the note:

After the lynching, Washington’s corpse was placed in a burlap bag and dragged around City Hall Plaza, through the main streets of Waco, and seven miles to Robinson, where a large black population resided. His charred corpse was hung for public display in front of a blacksmith shop.

A photograph of the burning of Jesse Washington, with a large white man pulling a chain to adjust him on the kindling like a slab of barbecue, provides the endpapers for Without Sanctuary. For many readers, the end-papers may be as far as they care to go; thematically that’s perhaps as far as they need to go, although they should, at least, turn to Plate 26 and see Jesse Washington’s corpse, on a postcard made of the event, which reads:

This is the Barbecue we had last night my picture is to the left with a cross over it your son Joe.

When Jesse Washington, who had “confessed” to the killing of a white woman, tried to climb the hot chain to escape the hotter flames, his fingers were cut off and distributed as souvenirs, as far as they went—not far, with a crowd of fifteen thousand. Exactly the same things happened to Sam House, in Newman, Georgia, in 1899, including a partial flaying; eager souvenir seekers at that lynching had to make do with knuckles or fragments of bone. Unfortunately the distribution of such grisly souvenirs is not unique to American lynchings; worldwide and across the ages the atrocity menu is much the same.

The busy reviewer, accustomed to speeding right through whatever book the postman drops on the porch, has to throw on the brakes here; as should, also, the casual buyer of slicked-up photography books. This is a book of horrors, and not all horrors are equal. My recommendation would be that the reader begin with Hilton Als’s angry—indeed, furious—prefatory essay:

Of course, one big difference between the people documented in these pictures and me is that I am not dead, have not been lynched or scalded or burned or whipped or stoned. But I have been looked at, watched, and it’s the experience of being watched, and seeing the harm in people’s eyes—that is the prelude to becoming a dead nigger, like those seen here, that has made me understand, finally, what the word “nigger” means, and why people have used it, and the way I use it here, now: as a metaphorical lynching before the real one. “Nigger” is a slow death. And that’s the slow death I feel all the time now, as a colored man.

And according to these pictures, I shouldn’t be talking to you right now: I’m a little on the nigger side, meant to be seen and not heard, my tongue hanged and with it, my mind…. Who wants to look at these pictures? Who are they all? When they look at these pictures, who do they identify with? The maimed, the tortured, the dead or the white people who maybe told some dumb nigger before they hanged him, You are all wrong, niggerish, outrageous, violent, disruptive, uncooperative, lazy, stinking, loud, difficult, obnoxious, stupid, angry, prejudiced, unreasonable, shiftless, no good, a liar, fucked up—the very words and criticism a colored writer is apt to come up against if he doesn’t do that woe-is-me Negro crap and has the temerity to ask not only why collect these pictures, but why does a colored point of view authenticate them, no matter what that colored person has to say?

Mr. Als then describes two incidents in which he himself, abruptly and for no good reason, was menaced by the police, menaced enough, I would think, for him to be able to speak with some authority about these pictures. In the time of Judge Lynch, innocence was, as the book’s title suggests, no sanctuary.

Advertisement

But some of the other questions Mr. Als asks are not so easily answered. Why do we, why should we, collect such pictures? The Irish writer Frank O’Connor maintained that you cannot make art of unredeemed pain. These pictures were hung as a “show,” in an art gallery, but the photographers who took them didn’t consider them to be art, they considered them to be emblems of racial pride. Leon Litwack, in his disturbing introduction to the collection, quotes this on-the-spot commentator at the lynching of Thomas Brooks in Fayette County, Tennessee, in 1915:

Hundreds of kodaks clicked all morning at the scene of the lynching…. Picture card photographers installed a portable printing press at the bridge and reaped a harvest in selling postcards showing a photograph of the lynched Negro. Women and children were there by the score….

A year later, in Abbeville, North Carolina, a very respectable black farmer named Anthony Crawford was lynched; Mr. Crawford’s well-established respectability prompted one witness to say this about his unexpectedly terrible end:

I reckon the crowd wouldn’t have been so bloodthirsty, only it’s been three years since they had any fun with the niggers, and it seems though they jest have to have a lynching every so often.

A willingness to select victims pretty much at random, often in the absence of any proven or even reported crime, suggests that these lynchings enact some base, communal dramaturgy, not wholly unlike what occurred in the witch-burning frenzies in northern Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and not wholly unlike, either, some of the repressed-memory molestation frenzies of our own time, one or two of them capable of sucking in whole communities.

Elias Canetti, in Crowds and Power, has this to say about the nature of crowds, such as the ones that conduct these lynchings:

One of the most striking traits of the inner life of a crowd is the feeling of being persecuted, a peculiar angry sensitiveness and irritability directed against those it has once and forever nominated as enemies. They can behave in any manner, harsh or conciliatory, cold or sympathetic, severe or mild—whatever they do will be interpreted as springing from an unshakable malevolence, a premeditated intention to destroy the crowd, openly or by stealth.

And:

The most important occurrence within the crowd is the discharge: before this the crowd does not actually exist; it is the discharge which creates it….

And, again, on the subject of crowd destructiveness:

A crowd setting fire to something feels irresistible; so long as the fire spreads everyone will join in and everything hostile will be destroyed….

Canetti is talking about burning buildings here, but the endpapers to Without Sanctuary and several pictures in it (particularly Plates 22 and 97) give us a glimpse of the crowd at just such a moment of irresistibility, while the discharge is occurring.

Many of the lynchers or lynching witnesses quoted in Mr. Litwack’s introduction confirm Canetti’s first point: that the persecutors felt themselves to be persecuted. “We whites,” one said, “have learnt to protect ourselves against the negro, just as we do against the yellow fever and the malaria—the work of noxious insects.” A federal official in Wilkinson County, Mississippi, said this: “When a nigger gets ideas the best thing to do is to get him under ground as quick as possible.”

Advertisement

Canetti’s analysis doesn’t answer quite all of Hilton Als’s questions, though. Why collect these pictures? Is it for the sake of history, for Clio, that gluttonous Muse, eater of darkness and light? Doesn’t history already know all it needs to know about man’s cruelty to man, or is every local or temporal detail, every minutely reported agony necessary to the files?

Viewed as history, this small sampling of pictures tells us that if you were black, Texas and Georgia were the worst places in America to live, and possibly still are. Not only the most lynchings but the cruelest seem to have occurred in those two states, though that may only be through a caprice of the selection process; given a larger grouping, Virginia, Mississippi, and Oklahoma might have scored high too.

More than three quarters of the victims shown here were black. There are twenty-five pictures or so of lynched white people but the difference in the state of the corpses only serves to emphasize the level of racism involved in lynching. The hanged white people were just criminals—bank robbers, stagecoach robbers, murderers. A few seem to have been roughed up a little but mainly they were just caught, and hanged, and that’s that. They weren’t stripped, burned, cut, whipped, or gouged. In contrast to what happened to the blacks, the whites hanged look almost seemly. As I said, the whites were just criminals; they weren’t witch-demons, devils, or the allies of devils, as the blacks were seen to be.

Among the hanged were two women, Ella Watson, better known as Cattle Kate, hung, as her postcard says, by cruel cattle barons in Wyoming in 1892; and Laura Nelson, a black woman hung with her son from a bridge near Okema, Oklahoma, in 1911. The son had killed a deputy sheriff and Laura Nelson had tried to defend him. James Allen, the picker or scout who was offered the postcard at a flea market, has this to say:

It was Laura Nelson hanging from a bridge, caught so pitiful and tattered and beyond retrieving—like a paper kite snagged on a utility wire.

The most recent photograph in the book, Plate 19, was taken in McDuffie County, Georgia, in 1960. Two boys on their way to a fishing hole found a black man hanging in a tangled thicket. It is one of the few pictures in the book in which no crowd is pushing in, eager to get in the picture or on the post card; this is in stark contrast to Plate 57, which shows the lynching of Rubin Stacy in Florida in 1935. Four little white girls in the front of the crowd are looking at Rubin Stacy’s corpse, one of them very pretty, smiling, smug. What the lonely lynching in 1960 and the crowded lynching in 1935 suggest is that in twenty-five years styles have changed; the civil rights movement is underway and even reliable sheriffs and like-minded judges had to be a little more cautious. The lynchers can’t afford to do quite so publicly what they were welcome to do, with complete assurance, to Rubin Stacy, Jesse Washington, Sam Hose, the respectable Anthony Crawford, and thousands more

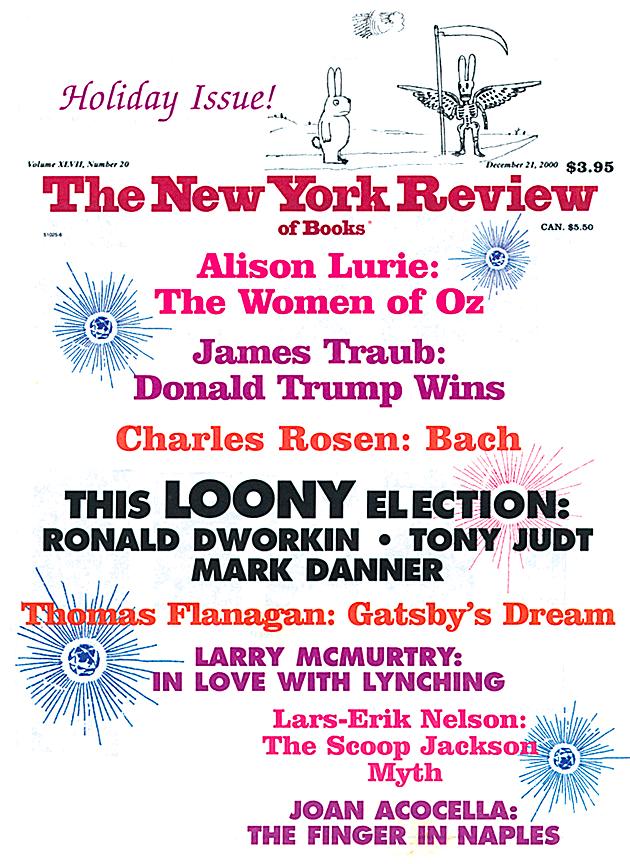

This Issue

December 21, 2000