As I write, the extraordinary 2000 presidential election remains undecided, because it remains uncertain which candidate will receive Florida’s twenty-five electoral votes. By the time this issue is published, the overseas ballots, the legal battles over manual recounts, or both, may finally have given Gore the presidency, or he may have conceded the presidency to Bush. Or the election may still be undecided, because recounts are continuing in Florida, or have been demanded in other states, or because lawsuits challenging the Florida electoral process, some of which have already been filed, are still pending. In any case, however, the election has raised a great number of new and perplexing legal and political issues, and it is important to confront these, for the future, whether or not the presidency still hinges on how they are decided.

Legitimacy is the issue. When an election is so close, and there are serious grounds for suspicion of inaccuracy in the count, how can officials decide who won in a way that the public should and would see as legitimate? It appears that Gore won the popular vote—according to the most recent reports, he received more votes across the country than Bush did. That fact has in itself no legal significance, of course, but neither does it have much moral significance. Which eligible voters actually voted—in fact approximately only 52 percent of them did—and for whom depended on a host of arbitrary factors or accidents. If the election had been held a day later or earlier, if the weather had been better in one place or worse in another, or if any number of other decisions or chance facts had been different, the popular vote would also have been different, and perhaps different enough to change who “won” it. There is much to be said against the Electoral College system—it gives individual voters in small states consistently more impact in presidential elections than those in large states, for example—but the fact that it permits the winner of the popular vote in a very close election to lose in the Electoral College is not one of them.

It is of central importance to the issue of legitimacy, however, whether more Florida voters actually intended to vote for Gore than for Bush, so that, if the Electoral College process had worked as it should, Gore would have won the state’s electoral votes and the presidency. The system did not work because the ballot in Palm Beach County was confusing, and many voters—perhaps more than twenty thousand—who intended to vote for Gore actually voted for Pat Buchanan or voted for two candidates and therefore found their ballots ignored. Nor would the system have worked if Gore finally wins because there was a manual recount only in heavily Democratic counties rather than in the whole state. Katherine Harris, the Florida secretary of state and co-chairman of the Bush campaign in Florida, has declared that no manual recounts submitted after November 14 will be counted. It is unclear as I write whether her ruling will be overturned, and, if it is, which counties will be recounted. Even a full manual recount in the entire state would not solve the central problem, moreover: if Gore still lost, the confusion in Palm Beach County would still raise doubts about the legitimacy of Bush’s presidency.

Some commentators urge that we simply accept the damaged result, because uncertainty and delay is against the public interest. But we have, in any case, a president and an administration until January, and though it is undoubtedly desirable to know who the new president will be as soon as possible, it would not be catastrophic for the nation and world to wait for a few weeks longer—it has been waiting months already—for the answer. Any harm that might come from a short period of delay and uncertainty must be balanced, moreover, against the harm, likely to be both more serious and much longer lasting, of inaugurating a president while a cloud of suspicion hangs over his election. Even if the public were apprehensive about the delay—many polls suggest that it is not1—and willing to accept the risk of an inaccurate result in exchange for a quick settlement, that sentiment would be unlikely to hold when the president makes bitterly controversial decisions—about, for example, the nomination of Supreme Court justices—and people are invited to remember that his election was dubious. Rushing the process to an untrustworthy conclusion seems the riskier course.

It is wrong, in any case, to consider the question of legitimacy solely or even largely as a matter of the public’s interest because individual rights—the right of each citizen not to be disenfranchised—are at stake. We would not decide whether some ordinance that limited the free speech of particular citizens was constitutional by asking whether the public wanted them to speak or whether the country would be better off if they did not, and we should not use that test to decide whether the basic rights of the voters of Palm Beach County were compromised. True, voters do not have a right to an electoral system that will guarantee perfect accuracy in a large national election: no such system exists. But they do have a right that whatever system has been established by law be respected, and there is a very strong argument that the now infamous “butterfly” ballot was not only confusing but inconsistent with Florida law.

Advertisement

The Florida code requires that the names of the two major-party presidential candidates be listed first on the ballot, with minority-party candidates below, and that the space for marking or punching a vote for a particular candidate be uniformly to the right of that candidate’s name.

The Palm Beach County ballot listed candidates not in one column as other counties did, but in two columns, placing Bush/Cheney in the highest box in the left column, Gore/Lieberman in the box below, and Buchanan/ Foster at the top of the right column slightly below the opposite Bush box and slightly above the opposite Gore box, and it placed voting holes not to the right of each candidate, but between the two columns. There were therefore two holes to the right of Gore’s box, and the first of these was actually Buchanan’s. An arrow in the Gore-Lieberman box pointed to the third hole, but many voters later said that they assumed that the second hole was Gore’s, as it should legally have been. Others said that they thought that there were two holes next to the Gore/Lieberman box because it was necessary to vote for each of those candidates separately, and others that they were uncertain where the arrow pointed and so punched out both of the holes next to the Gore box in order to make sure that they voted for him. All ballots with two holes punched—over 19,000 of them—were thrown out altogether. Statistical models show that both the Buchanan vote and the number of excluded double-punched ballots was much higher than the demography of the county or the results in comparable counties would have predicted.2

What is the appropriate remedy when it is discovered that a completed election was in some important respect illegal? A new election would be expensive and cause delay, and would be unlikely in any case to produce the same result as a legal ballot would have produced on election day. In Palm Beach County, for example, many of those who voted for Ralph Nader on November 7 might well vote for Gore in a rerun. Scholars have suggested a variety of other solutions: that Florida’s Supreme Court order it to send no electors to the Electoral College, for example, or that it divide Florida’s electoral votes thirteen for Bush and twelve for Gore. But it would be unprecedented for a court to make any such radical change in a state’s electoral procedures, and each of these solutions could be attacked as arbitrary and political. (Either would automatically make Gore president.)

Many lawyers have therefore argued that there should be no remedy at all: some innocent violations of complex elections laws are inevitable in any national election, they say, such mistakes are sufficiently random so as not to benefit any one party or group or region in the long run, and trying to correct them would involve awkward procedures that would inevitably make our electoral process more clumsy and litigious. If a new election were ordered in Palm Beach County, they warn, then every presidential election for decades would be followed by lawsuits demanding repeat elections in different counties across the nation.

That argument seems decisive against allowing new elections in marginal cases, or when nothing important turns on how the county in which the error is alleged has voted. But it would be wrong to declare, as a flat rule, that no remedy is ever available for demonstrable and grave illegality in the electoral process, no matter how clear the mistake or how evident that it changed the final national result, because that would value the right to vote too cheaply. We do not need so absolute a disclaimer of judicial power to ensure that future elections are not routinely decided in court, and no court, as far as I am aware, has suggested it. The Florida Supreme Court recently insisted, for example, that Florida courts have “authority to void an election” when “reasonable doubt exists as to whether a certified election expressed the will of the voters…even in the absence of fraud or intentional wrongdoing.”3 Courts in Florida and in other jurisdictions have ordered new elections when the mistake was not as serious or the results so grave as in the Palm Beach County case.4

Advertisement

So we should consider what standard for ordering a new election would recognize the crucial importance of the right to vote but nevertheless rarely encourage politicians to seek such an order. Such a standard might provide, for example, that an election will not be voided for a non-fraudulent mistake unless the following four conditions are clearly demonstrated: (1) that the electoral process violated legal requirements; (2) that the violation more likely than not created a result significantly different from what those who voted collectively intended; (3) that based on available evidence, including evidence about vote totals and challenges in other states, the overall result of the election—in this case, the national election of a president—would have been different had the violation not occurred; and (4) that a new election could be designed so that the result could be expected to be closer to what the voters originally collectively intended. The burden of proof with respect to each element would be on the party seeking the order. This standard does respect the high importance of the right to vote: it allows a new election when there is a substantial chance that the violation of that right defeated the result that the disenfranchised voters hoped to help realize. But it is not likely to encourage much litigation in the future. It is, after all, forty years since the last occasion when it was even suggested that a legal challenge might change a presidential election.5

We do not know whether this standard would permit a new election if applied to the Palm Beach County case: the facts have not yet been examined in any court, and may never be.6 But it is important that we continue to study and debate, even after the 2000 presidential election is finally over, how our electoral process can be improved in the light of what that election revealed, and focusing on the appropriate conditions for a local rerun should be part of that discussion. Allowing important electoral safeguards to be fashioned, tested, and enforced in court is not, as many have claimed, a corruption of our democracy. On the contrary, it is an affirmation of our democracy’s strength; even when elections are breathtakingly close, we settle them on the basis of examined principle and not in the streets.

—November 15, 2000

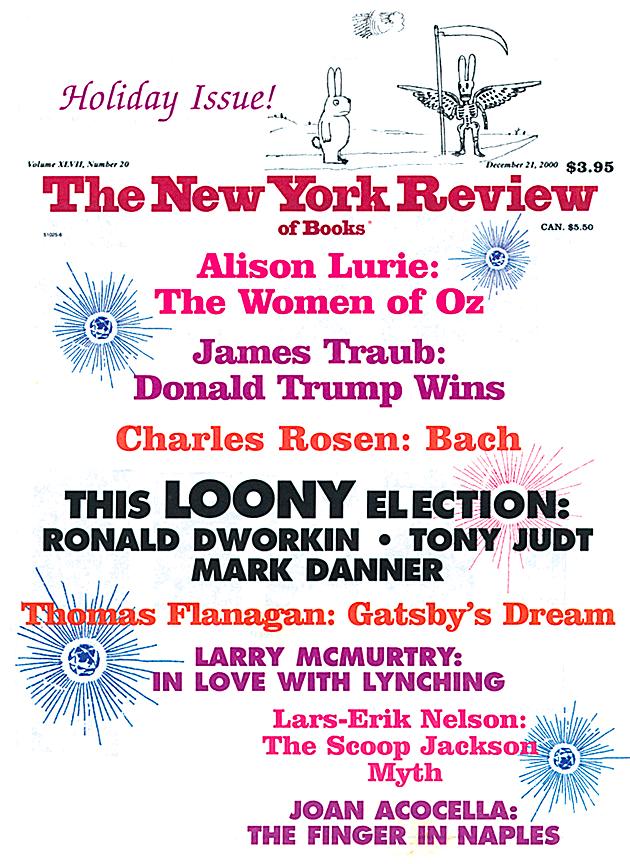

This Issue

December 21, 2000

-

1

See “Americans Patiently Awaiting Election Outcome,” The New York Times, November 14, 2000, p. A1. ↩

-

2

For a sample analysis, see the article posted on the Web at madison.hss.cmu. edu. ↩

-

3

Beckstrom v. Volusia County Canvassing Board, 707 So. 2d 720 (1998). ↩

-

4

See, for example, Craig v. Wallace, 2 Fla. L. Weekly Supp. 517a (1994), Ury v. Santee, 303 F. Supp. 119 (N.D. Ill. 1969), Akizaki v. Fong, 461 P.2d 221 (Haw. 1969), and Adkins v. Huckabay,755 So. 2d 206 (La. 2000). ↩

-

5

Republicans charged illegality in the vote count in Illinois and Texas in the 1960 election, and switching the electoral votes of those two states would have changed the result. Some commentators hail Nixon’s decision not to challenge as an act of patriotism, though others say he feared discovery of Republican as well as Democratic fraud in Illinois. ↩

-

6

Would the result of a new election in that county be closer to original intentions than the recorded first vote was? Professor Laurence Tribe of Harvard suggested in The New York Times of November 12 that any new election be limited to those who voted in the first one, and that the votes for Bush and Nader should be held at their initial totals, so that only the votes for Gore and Buchanan could change. ↩