1.

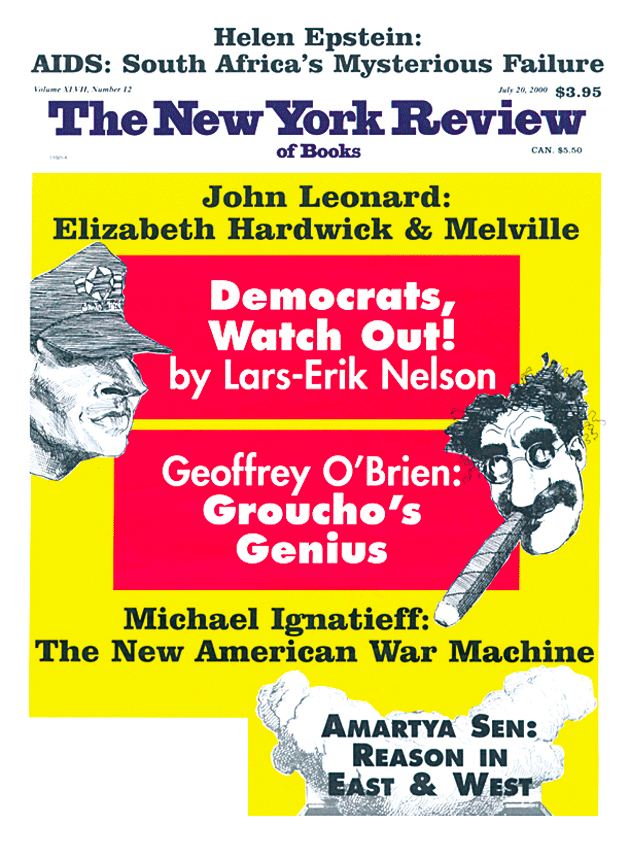

The things about the Marx Brothers that most people remember—that they obsess over and memorize and if they are feeling reckless even try to imitate—are found in seven films made between 1929 and 1937. The brothers made another six movies after that, culminating in the dreary and impoverished Love Happy in 1950, but the comic frenzy subsided after A Day at the Races. While Groucho went on to a second career as television’s most (or perhaps only) memorable quizmaster in You Bet Your Life, which ran from 1950 to 1961 and persisted long after in reruns, Chico and Harpo found few performance opportunities after the movies dried up. (Gummo and Zeppo, the younger brothers who had in earlier phases been part of the act, had long since dropped out.)

Yet The Cocoanuts, the primordial talkie they filmed in Astoria in 1929, represented a rather late milestone in their career. Chico, the oldest of the brothers, was already forty-two, and had been playing piano in honky tonks, nickelodeons, and beer gardens since his mid-teens (he had already, according to family lore, established his penchant for gambling and bad company before the nineteenth century was out); Harpo had followed Chico into the saloons and mastered his older brother’s limited piano repertoire (which for a long time apparently consisted of a single song, “Waltz Me Around Again, Willie”). Groucho, born in 1890, had been performing professionally since his fifteenth year: how far his roots go back can be measured by his appearance in a benefit for victims of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, on a bill featuring Yvette Guilbert and Lillian Russell.

In those days they were Leonard, Adolph, and Julius; the familiar nicknames were bestowed by a theatrical friend during a poker session around 1914. The personae that went with the nicknames evolved in hit-or-miss fashion through years of more or less improvised, more or less chaotic wanderings—as the Three Nightingales or the Six Mascots, with or without their mother Minnie or their aunt Hannah, with or without their failed tailor of a father planted in the audience to egg on the laughter—over most of the United States, mostly in the lower, small-time echelons of vaudeville. The chief fascination of both recent studies of Groucho and his brothers, Stefan Kanfer’s Groucho and Simon Louvish’s Monkey Business, lies in what they can tell about these lost decades in which the Marxes invented their art. The frustration is that they can after all tell so little. A few fragments of script, some rare photos, some not very revealing contemporary reviews, and the unreliable anecdotes in memoirs written long after the fact: from such remnants a world must be imagined.

It is worth imagining, that domain (in Harpo’s words) of “stale bread pudding, bug-ridden hotels, crooked managers, and trudging from town to town like unwanted gypsies,” into which Groucho was sent out at fifteen—his education halted permanently at his mother’s insistence—to be robbed by his employers and given a dose of gonorrhea by the first woman he slept with, a domain whose Hobbesian realities were matched only by the desperate energy of its tattered amusements. “In a typical week,” writes Stefan Kanfer of the life the brothers led around 1912, “they might play three days in Burlington, Iowa, catch the overnight train and play the following four days in Waterloo—four-a-day vaudeville for five days, five-a-day for two days, for a total of thirty shows per week. The process went on unvaryingly, in the cities around the Great Lakes, in Ohio, Illinois, Texas, Alabama.”

Perhaps one would not really want to savor every phase of that long and miserable pilgrimage, to watch the young Julius making his 1905 debut in drag with the Leroy Trio before being stranded in Cripple Creek, Colorado, where Mr. Leroy absconded with all the money, and then setting out once again, touring Texas with an English “coster singer and comedienne” named Lily Seville, a pair of clog dancers, and a seventy-four-year-old tenor. The Dallas Morning News for December 25, 1905, remarked: “Master Marx is a boy tenor, who introduces bits of Jewish character from the East Side of New York.”

He and his brothers weren’t of course the only wild kids of the road. There was an army of them. The children who performed with Gus Edwards’s famous troupe (Groucho did his bit with Edwards’s “Postal Telegraph Boys” in 1906) included George Jessel, Eddie Cantor, Ray Bolger, Eleanor Powell, Ricardo Cortez, Mervyn LeRoy, and Walter Winchell, a successful handful among the vast and largely threadbare host of small-timers who sustained their internal migrations from the Gilded Age until the circuits began petering out in the Twenties. An army of the lost: we must be content with what we can glimpse in S.J. Perelman’s recollections of an early Marx Brothers appearance that also featured

Advertisement

Fink’s Trained Mules, Willie West & McGinty in their deathless housebuilding routine, Lieutenant Gitz-Rice declaiming “Mandalay” through a pharynx swollen with emotion and coryza, and that liveliest of nightingales, Grace Larue.

If the Marx Brothers’ work is “about” anything, it is about survival in that world. Half-grown, without training or material, they were thrust into the business of entertainment, and it took them two decades to fight their way to the Broadway opening in 1924 of I’ll Say She Is!, the show that finally sealed their fame. The legend of how their mother Minnie turned them into performers by main force has been well rehearsed, beginning with press releases overseen by the brothers and culminating in 1970 in the Broadway musical Minnie’s Boys (co-written by Groucho’s son Arthur). Indeed, the whole early history of the Marx Brothers was carefully remade by them and their chosen publicists, and both Kanfer and Louvish become enmeshed in layers of deliberate mythmaking and minute misrepresentation of such simple things as dates and locations. Even in their memoirs Harpo and Groucho consistently took five years off their ages, and the internal contradictions in the various anecdotal histories of the family make any precise account of their doings virtually impossible. The family’s life in the three-room East 93rd Street apartment where they lived from 1895 to 1909, a life crowded with relatives and visiting show business types, can only be envisioned as an unknowable but presumably chaotic corollary of the world of their films.

The centrality of their mother in their career resulted to some extent from the fecklessness of their father, an immigrant tailor from Alsace more devoted to cooking and pinochle than to his chosen profession. As the daughter of an itinerant Prussian ventriloquist and magician and the sister of the increasingly successful vaudevillian Al Shean (of Gallagher and Shean), Minnie had every reason to be drawn to show business. The alternatives were not many or appealing, and her sons—excepting the bookish Groucho—showed early tendencies to drift into the life of the street. So she sent her children on the road and eventually set about building her own show business empire, moving the family from New York to Chicago, managing not only her sons but a string of other troupes with names like the Golden Gate Girls, Palmer’s Cabaret Review, and the Six American Beauties. It may be, as Simon Louvish surmises, that “being Minnie’s Boys was a bad career move” and that their mother’s managerial flaws—her empire was short-lived—may have made the boys’ progression toward stardom unduly slow, but what we appreciate in the brothers’ art has everything to do precisely with its slow and familial evolution.

2.

The Marx Brothers create a world because they have no other choice. They start from no plan or idea but proceed by groping and trying out, grabbing at any material that offers itself. Everything takes shape through an accretion of bits. “I was just kidding around one day and started to walk funny,” Groucho wrote. “The audience liked it, so I kept it in. I would try a line and leave it in too if it got a laugh. If it didn’t, I’d take it out and put in another. Pretty soon I had a character.” The phrase “pretty soon” covers years of experiment. For a long time Groucho’s persona was a comic German, until the sinking of the Lusitania made Germans less than comic. The German bits became Yiddish bits, until these were sloughed off in turn and he made the crucial transition into a character not dependent on dialect. (Chico, on the other hand, stuck with his Italian persona to the bitter end.) It took years, likewise, for Harpo to understand that he had no gift for verbal comedy and remake himself as a silent clown.

Their performances remain breathtaking because of a moment-by-moment control and rapport that distills years of trial and error. This was comedy as experimental science, and the experiment was conducted under the most prolonged and uncomfortable circumstances. Years later, when studio filmmaking threatened to dull their instincts, the brothers attempted to regain intimacy with the audience by trying out the script for A Day at the Races on the road. One of the publicists recalled how Groucho’s line “That’s the most nauseating proposition I ever had” was arrived at:

Among other words tried out were obnoxious, revolting, disgusting, offensive, repulsive, disagreeable, and distasteful. The last two of these words never got more than titters. The others elicited various degrees of ha-has. But nauseating drew roars. I asked Groucho why that was so. “I don’t know. I really don’t care. I only know the audiences told us it was funny.”

It was an apprenticeship of a kind no one has time for anymore, nor indeed would one wish it on anyone. It only took them twenty years to become geniuses. “They had absolutely no marketable skill outside of comedy,” writes Kanfer, “and they instinctively rode that skill as far as it would take them.” Their finesse was acquired in the roughest of schools, where a pause, even the most momentary relinquishment of control, would be fatal. Even if they were brilliant in a field populated largely by the not so bright, witty in an area where wit came cut in broad slabs, imaginative where the rule was to grind out every last possible bit of juice from repeated and imitated and stolen routines, it was still not quite enough to guarantee success. The final ingredient was an unparalleled ferocity. The rule had to be: No mercy, no exceptions, no leeway for the audience to think or resist.

Advertisement

All vaudevillians practiced a cer-tain savagery in their assault on the audience, but often the savagery came disguised in the form of heart-warming sentiment or reverential high-mindedness. The Marx Brothers were not interested in eliciting sympathy. Even the sentimental trappings of the later films—where the brothers figure as benign eccentrics rescuing star-crossed lovers, and the infantile ecstasies of Harpo assume an ever more self-consciously beatific aura—cannot altogether conceal a persistent kernel of exhilarating heartlessness. Not malice: simply comedy in its most cold-eyed state. In The Cocoanuts (1929) and Animal Crackers (1930) the violent energy of the stage performances is still palpable. Harpo’s emergence into the frame, on the heels of a blond parlor maid, registers as a chaotic intrusion the camera can barely capture. Groucho’s verbal assaults are flanked by the downright menacing physical comedy of Chico and Harpo.

The roughness was as real offscreen as on. There were other worlds where the brothers might have flourished outside of show business. Zeppo carried a gun and stole automobiles; Chico became a chronic gambler at an early age, around the same time he was beginning his career of relentless womanizing (“Chico’s friends,” according to Gummo, “were producers who gambled, actors who gambled, and women who screwed”); Harpo at one point fooled around with Legs Diamond’s girlfriend. The ending of Horse Feathers, when the brothers collectively marry Thelma Todd and then jump on her at the fadeout, was evidently mirrored when some of the brothers felt obliged to proposition the bride of the newly married Chico. As Chico’s daughter Maxine remarked in a memoir, “Years of touring the hinterlands, seeing the uglier side of people and life, made the boys callous and insensitive. In the world known to the Marx Brothers, only the fittest survived…. If Betty couldn’t take care of herself, too bad.”

3.

The Marx Brothers repeatedly saved themselves by leaping from one declining medium to another. As vaudeville slowly expired, they switched to the Broadway musical; when lavish Broadway musicals went into decline after the crash of 1929, they escaped into the movies. Groucho at least was finally able to adapt his persona for television, exchanging his greasepaint moustache for a real one and toning down his verbal pyrotechnics into a more manageable blend of insult humor and mild double-entendres. Always they seemed to belong more to the past than the future. Fugitives from a livelier and more elemental world, potentially dangerous primitives, they brought a demonic whiff of the comedic lower depths into the polite drawing rooms of Broadway comedy.

High culture was eager to make them its own. They symbolized authenticity to jaded theatrical types and New York intellectuals, with the semiliterate Harpo inducted by Alexander Woollcott into the Algonquin circle, and fashionable revelers attending theme parties dressed as the Marx brother of their choice. After the movies, the admiration was global. Graham Greene felt that “like the Elizabethans, they need only a chair, a painted tree,” while Antonin Artaud spoke of “essential liberation” and “destruction of all reality in the mind.” Salvador Dalí incorporated Harpo into paintings and sent him a scenario for a Marx Brothers movie to be titled Giraffes on Horseback Salad, whose humorous potential can be gauged from the scene where Groucho tells Harpo: “Bring me the eighteen smallest dwarfs in the city.”

Fortunately the brothers’ scripts were written not by Dalí but by George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind and S.J. Perelman—not to mention Harry Ruby and Bert Kalmar, responsible not only for specialty songs like “Hurray for Captain Spalding” and “Whatever It Is, I’m Against It” but for the best script of all, Duck Soup. If their timing and personae were their own creations, the Marx Brothers owed much to the writers who expanded the scope of their material beyond such earlier hodgepodges as “Fun in Hi Skule” and “On the Mezzanine Floor.” The brothers may have chafed at opening up their closed world to a circle of collaborators—Perelman had a terrible experience with the brothers and later described Groucho as “one of the most detestable people I ever met”—but it was a collective process that resulted in the comic density of the Paramount films.

Without some very lucky timing we wouldn’t have anything like Horse Feathers and Duck Soup, and without them we probably wouldn’t remember the Marx Brothers at all. It was only for a brief interval—from the advent of sound to around 1934—that Hollywood, faced with a new market for talking pictures, allowed an assortment of hams, clowns, double-talkers, and carny spielers to cut loose on screen with a freedom that would be curtailed soon enough. Order would be reimposed in the form of logically (if not plausibly) constructed screenplays, and decency reasserted by means of the Motion Picture Code, putting an end to lines like Groucho’s “Signor Ravelli’s first performance will be ‘Somewhere My Love Lies Sleeping’ with a male chorus.”‘

When young cinephiles rediscovered the Marx Brothers in the 1960s, the haphazard structure of the Paramount movies seemed a prophetic radicalism, with Groucho as master saboteur of linear convention. It hardly mattered that one had to sit through interminable harp and piano interludes, or that Horse Feathers, for instance, ran out of steam well before the end of the last reel. To transform a lineup of college deans into a minstrel show chorus, turn puns into blueprints for action (so that a deck of cards can only be cut with an ax), insult society matrons and randomly chase blondes down hotel corridors, cheerfully go to war because of the month’s rent already paid on the battlefield: the anticipation of such moments encouraged endless repeat viewings of Mon-key Business and Horse Feathers and Duck Soup, simply to soak up an atmosphere of total permission found nowhere else. Greed, lechery, the sheer desire to subvert every attempt at etiquette and rational conversation: no impulse went unindulged. Satire had almost nothing to do with it. The Marx Brothers provided a series of interruptions, the more brutal the better; any fixed image, any stable situation or relationship had to be disrupted as soon as it began to solidify:

GROUCHO: …I suppose you’ll think me a sentimental piece of fluff, but would you mind giving me a lock of your hair?

MRS. TEASDALE: (Coy) A lock of my hair? Why, I had no idea….

GROUCHO: I’m letting you off easy. I was going to ask for the whole wig.

This was disruption as bliss, the paradise of impudence, and with Groucho as commander in chief there was the sense that a superior intelligence had decreed the dismantling of intelligence itself.

4.

I do not know what one might hope to find in a biography of Groucho Marx, beyond the accumulation of small facts that both Stefan Kanfer and Simon Louvish supply in abundance. Louvish’s book, useful as it often is, is marred almost fatally by a tic of nervous jokiness and rib-jabbing overemphasis that makes for tortuous reading. A pity, since Louvish has in many ways done a more thorough and sometimes more skeptical excavation of the historical record, offering a great deal of information missing in Kanfer. Kanfer’s Groucho, on the other hand, is a firmly constructed, emotionally coherent study of a man who, by the time the end is reached, seems like an oddly inadequate subject for a biography. All that is most interesting about Groucho is either on the screen or lost to history.

Instead we find ourselves living, at what comes to seem like inordinate length, a slow and painful decline culminating in scenes of grotesque confrontation—the custody battle between Groucho’s children and his last companion, Erin Fleming—scenes of which the ailing Groucho may not have been fully aware. The lacunae of the formative years give way to the excessive detail of our own era, offering more material than can be drawn on: letters and films, memoirs and magazine articles, radio and television transcriptions, and, not least, legal depositions. We move from an age of legend to an age of forensic scrutiny, and end up learning too much about what we might really not want to know, while remaining famished for what will always be beyond knowing.

The real history of Groucho Marx would be the story of how he assembled himself as a public character, but we cannot have that. There are fascinating if unsatisfying glimpses in some of the old newspaper reviews, as when Variety comments in 1919 that

Julius Marx is developing into an actor. He shows flashes of Louis Mahn, at least a chemical trace of David Wakefield and at times reflects the canny technique of Barney Bernard. Julius has a strongly defined sense of humour. His asides are more funny than the set lines.

But we cannot trace in any detail the process by which Julius turned himself into the fully emerged creation we encounter in the opening monologue of The Cocoanuts. We know some of the things that happened to him early on: that he read Horatio Alger and Frank Merriwell; that he dreamed of becoming a doctor before his mother yanked him out of school to go on the road at fifteen; that she called him der Eifersüchtige, “the jealous one,” an unusually telling detail rescued from the Marx family lore.

For the rest of it—the part not spent on stage or in front of cameras—there are the three failed marriages and, in his eighties, the disastrous final liaison (“women,” wrote his niece, “were never his strong point”), the strained relations with his three children (he doted on them in childhood and appeared to lose interest when they reached adulthood), the chronic insomnia, the penny-pinching that became obsessive after he lost his fortune in the stock market crash and persisted long after he recouped it, the resentful sense of inadequacy in the company of literary contemporaries like Kaufman, Perelman, and Woollcott. He prided himself on his acquaintance with T.S. Eliot, who avowed himself a fanatic Groucho fan, but close, extended friendships seem to have been rare in his life. He was closer to his brothers than to anyone else, but after the first few movies they kept their distance from one another; the years on the road had taken their toll on fraternal bonding. He seems to have been at his happiest at home alone with his guitar and his Gilbert and Sullivan records.

In one anecdote after another, Groucho is revealed as a disappointed and often disappointing man. Maureen O’Sullivan, with whom he became infatuated during the filming of A Day at the Races, described his courtship as an endless comic monologue: “After a while your face starts to crack. I was tired of it after the third day. I told him, ‘Please, Groucho, stop! Let’s have a nice quiet normal conversation.’ Groucho never knew how to talk normally. His life was his jokes.”‘ In private life, we are told, he often employed his comic gifts to humiliate wives, waiters, and other hapless victims. Harpo’s wife Susan remarked devastatingly: “He destroys people’s ego. If you’re vulnerable, you have absolutely no protection from Groucho. He can only be controlled if he has respect for you. But if he loses respect you’re dead.”

We already knew that it isn’t easy being funny, especially if you’re funnier than practically anyone else. If a whole body of literary speculation can evolve around the question of how it felt to be Marilyn Monroe, there is little likelihood of comparable investigations into the inner reality of being Groucho. Maybe we suspect that we already know the answer: that the real Groucho is indeed the one at whose routines we are laughing, and that all the rest was an unfortunate interlude or epilogue. The intimacy of Groucho’s comedy—and it is as intimate as one’s own thought rhythms, one’s own responses that one finds already anticipated by him—at the same time precludes the very possibility of intimacy. Beyond the mask there is nothing. He endears himself by eschewing all possibility of endearment, with a brutal honesty that makes all the other comedians look like sentimental hypocrites.

There is none of that “But seriously, folks” reflex: he is serious when he kids most viciously. Charm is reserved for Chico, with his smile of instant seduction; the Saint Francis-like appreciation of children and nature for Harpo. Groucho’s lot is total intelligence without an ounce of charity. In Horse Feathers, there is a beguiling Kalmar and Ruby ballad, “Everyone Says I Love You,” that each of the brothers gets to sing (or play) in turn. When at last it’s Groucho’s round, the playful love lyrics turn to pure gall—

Everyone says I love you

But just what they say it for I never knew

It’s just inviting trouble for the poor sucker who

Says I love you—

and you know he means it.

The Essential Groucho, Kanfer’s companion compilation of bits and excerpts from movies, radio, TV, and Groucho’s modest output of books and articles, demonstrates that in fact Groucho’s essence lies elsewhere. It’s not the words he speaks but how he speaks them that makes Groucho a supreme comic figure, certainly the most durable of the sound period. The words he wrote are something else again, a mostly disappointing mimicry of contemporaries like Perelman, Thurber, and Kaufman; as for the celebrated ad-libs from You Bet Your Life, at this point they come across as not so funny and not so ad-libbed.

If the scripts alone survived, I doubt that Groucho would concern us much. The handful of overfamiliar quips have little to do with his continuing fascination. The essential Groucho is not on the page but on the screen: the voice, the walk, the little jigs which over time have become as elegant as Astaire. We can even catch glimpses of the inner life elsewhere so elusive, in those moods of melancholy reverie that he sometimes adopts only to dissolve them into travesty. For a moment we might think we are seeing the face of the boy soprano who mimicked adult voices on stage before his voice broke, so that his adult voice when it emerged was imbued from the start with a long experience of parody and dissimulation.

His routines remain an unsurpassed compendium of parodistic possibilities, shifting as quickly as the inflections of Groucho’s voice and body language: mock-grief, mock-terror, mock- piety, mock-sternness, mock-bonhomie, the ten thousand shadings of unctuousness and inane good cheer. The speed of reception is taken for granted, since the original intended audience was presumed to have sat through years of stock comedy set-ups, tear-jerking ballads, rote melodrama, incompetent jugglery and acrobatics, to have internalized the American repertoire of electioneering, sermonizing, and unrestrained huckstering. The inflections change but the voice—the voice of the flim-flam man so self-confident that he can afford to expose his own con even as he works it—remains curiously constant. It is a tone that can never quite come to rest, a voice that finally undermines its own authority as it does everything else. There is always some additional comment, some pun to cap the pun that came before, some further dissolution to which language can be subjected.

The work leaves an abiding impression of extraordinary richness, even if the life may have had its share of emotional barrenness. The latter part of Groucho’s career was centered on what he lacked, on the depths he failed to sound. He faulted himself for not being the writer he felt he should have been, and probably failed to appreciate fully the singularity of what he had created. He had put the best of himself in full view, embodying a character of Shakespearean dimensions who only lacks a play to be part of. Instead of a play, he had brothers.

This Issue

July 20, 2000