The genre we call “true crime,” obviously one of the very oldest in literature, has, despite a biblical pedigree, spent much of its career in the literary slums. The genre from which it is adjectivally distinguished—although seldom referred to as “false crime”—has produced classics as well as potboilers, but the nonfictional narrative of crime has chiefly been associated with such raffish vehicles as the ballad broadside, the penny dreadful, the tabloid extra, the pulp detective magazine, and the current pestilence of paperbacks uniform in their one-sentence paragraphs, two-word titles, and covers with black backgrounds, white letters, and obligatory splash of blood. There’s really nothing wrong with any of these—even the current paperbacks are bound to seem more charming as time passes. Still, you might wonder: Where is the Homer of true crime, its Cervantes, its Dostoyevsky?

William Roughead might at least be its Henry James. The two were friends and correspondents, and they shared a variety of interests and inclinations: complex characters, hopelessly tangled motives, labyrinths of nuance, arcane language, byzantine sentence structure. Roughead was a Scotsman who was born in 1870 and died in 1952, although the unknowing reader would be forgiven for ascribing to him a set of dates several decades earlier, so resolutely unmodern is his prose—not that it is in any way stiff, cold, musty, or particularly quaint. He began his career at twenty-three as a Writer to the Signet, a term that has no literary implication, referring rather to an elite body of Scottish attorneys. He was in fact a lawyer, and his passion for the law extended well beyond his actual duties. As he notes in passing several times herein, he was from his youth both a frequent spectator at major trials and an indefatigable collector of newspaper clippings on criminal cases that interested him, and he went on to edit a number of the volumes in the celebrated Notable British Trials series, then to collect his commentaries in books issued by a small press in Edinburgh. His works were taken up by a commercial publisher only when he was in his sixties.*

So mercantile calculation clearly played no part in determining his choice of pursuits. His was one of those astoundingly ambitious Edwardian hobbies that differed from professions only in their lack of financial compensation—it was a time when every retired general seemed to be translating Hesiod and every diplomat apparently had a sideline in paleontology. In Roughead we can observe the most sophisticated and refined expression of the British middle-class armchair fascination with crime. When, in “The West Port Murders,” Roughead invites us to look over his shoulder at “an inch-square bit of brown leather” that is in fact a fragment of the tanned skin of the murderer and ghoul William Burke, handed down by the author’s grandfather, the scene—we imagine Roughead wearing a dressing gown and a velvet cap, examining the grisly relic with a bone-handled magnifying glass—contains in full that collision, of placid, well-furnished, and obsessively well-organized pedantry with savage howling atavism, that is the keynote of the fascination.

Virtually all the hallmarks of the classic British mystery appear here, the apparent originals of all those overly clever poisonings, those horrors in sleepy priories and dramas set against majestic Highland backdrops, those appallingly unlikely suspects and convenient foreign scapegoats, those algebra-problem alibi timetables, those ever-present watchful servants, those pathetically mundane overlooked clues. These cases have an advantage over their fictional descendants, however, by virtue of their mess, complication, frequent lack of satisfactory closure, and of course their psychological depth. They are anything but cozy. Roughead is not especially interested in clever paradoxes and neat resolutions; in fact he is not nearly as fascinated by the clue- hunting and deductive cogitation aspects of his cases as he is by their elaboration in the courtroom. A murder for him is of interest chiefly insofar as it provides the premise for a rich, complex trial at which personalities can clash, unfold, reveal their wrinkles.

Personality is the tie that binds together the twelve otherwise relatively disparate cases that make up Classic Crimes. They are mostly murders but not all, and are mostly but not all set in Scotland. Roughead writes about cases he observed himself, but he also delves into the archived transcripts and writes vividly of cases that took place a century or more before his birth. The protagonist can be obviously guilty, or obviously guilty but nevertheless released or acquitted, or falsely accused, or even, as in “Katharine Nairn,” not accused at all, as the slippery Anne Clark—the cousin who in Roughead’s words was “the evil genius” of the household—steals every scene of that particular show, despite its title. At their best, trial transcripts combine theatrical movement, interplay, and suspense with the voyeuristic fascination presented by someone else’s open trunk. They can supply all the ingredients for a sophisticated and modernistically jagged portrait, but it takes someone like Roughead to know how to extract and display those ingredients without losing momentum to procedural detours and longueurs—courtroom scenes have, after all, produced some of the most deadly boring stretches in movie history.

Advertisement

Roughead, with his jeweler’s eye for extravagantly serpentine characters, his taste for unresolvable conflicts, self-devouring schemes, and barely decipherable motives, his pleasure in stories that disdain such conventions as that of possessing a clear-cut beginning, middle, and end, is something of a cubist posing as a fogey. His own personality, vivid at every moment even when he is not actually an actor in the scene, is fundamental to his strategy, and to his charm. He is certainly no shrinking violet, and neither is he one of those rigorously deadpan journalists who insist on letting the facts speak for themselves. He is at once stage manager (“and now I am free to disclose an astonishing incident with which I have been longing to confound the reader…”), color commentator (“I have often wondered that no philosopher has considered the strange affinity between crime and whiskers”), handicapper (“in the kennel of ‘dirty dogs’ called Pritchard, the scurviest, to my mind, was the particular cur that instructed the line of defence”), gossip (“[the] two constables…would have made a fine appearance in the chorus of The Pirates, but as investigators of a possible crime they were lamentably incompetent”), and final-appeals judge.

He is relentlessly discursive, his asides convincingly sounding as if they are being whispered along a bench, and digressive, too, although his sense of timing is superb—he’ll take the reader on a walk through the past or through the neighborhood, but always be back in time for the crucial next question (“we may take advantage of this interval between the acts to identify the skeleton thus evoked by Mrs. Cox from the cupboard of her friend and benefactress”). There are, to be sure, thickets of local reference and forgotten allusion, and he seldom fails to introduce a barrister without summarizing the now obscure highlights of his illustrious later career, but the reader can simply file these under “atmosphere.”

Roughead’s prose represents the full range of the English language, circa 1880, as played on a cathedral organ with the largest possible number of manuals, pedals, and stops. He traffics in rare words, disused expressions, abstruse variants, and strictly local idioms, deploying them for reasons that are sometimes historical, sometimes psychological, often shamelessly musical. You can open the book anywhere and light on a random sentence—for instance, “The secret marauder came and went without a trace, save for the empty till, the rifled scrutoire, or the displenished plate-chest that testified to his visitation.” Numerous ways exist of expressing this thought that would convey all the essential information in fewer and more austere terms, but that “scrutoire,” that “displenished” have a majesty about them that at once relates to the magnificence of the marauder’s character—the flamboyant Deacon Brodie, who combined the profession of cabinetmaker, the position of member of the town council, and the avocation of burglar—and gives a glimpse of his times, the 1780s. And anyway, the sentence gives pleasure, well beyond any question of utility. The usages herein may often send the reader to the dictionary, sometimes even to the OED. The word does not even have to be unusual in itself; I was baffled by his use of “ghostly” (as in “Constance Kent…was admitted an inmate of St. Mary’s Home… under the ghostly ward of the Rev. Arthur Wagner…”) until I realized that Roughead invariably employs it as a synonym for “spiritual.”

These are twelve strong stories. One of them, the tale of the ghouls Burke and Hare, will be familiar to most readers, at least in outline, from Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Body Snatcher (and its superb 1945 Val Lewton film adaptation). The rest are discoveries: “Katharine Nairn” discloses the chaos and squalor of the eighteenth-century Scottish gentry. Madeleine Smith, who although she was acquitted almost certainly poisoned her lover, and who maintained an imperturbable cool throughout her trial and afterward, so that half a century later Roughead appears to still be more than a little in love with her, might be the prototype of the lethal film noir heroine. The belowstairs drama of “The Sandyford Mystery” all but calls for a floor plan and a stopwatch. “Dr. Pritchard Revisited,” with its grandiloquent quack subject—“the prettiest liar…ever known in those parts”—deserves a stage performance, and “The Arran Murder,” with its extravagant scenery and complex escape route, suggests a great lost Hitchcock movie. If the Balham mystery is something of a black hole in which any number of people can appear guilty, the Ardlamont and Merrett mysteries are black comedies, the tissues of lies of their defendants (the guardian of an “accident victim” and the son of a “suicide,” respectively) so thin and apparently permeable the wonder is how they thought they could fool anyone—but they did.

Advertisement

And finally there is the bizarre, protracted miscarriage of justice that is the case of Oscar Slater, one that invites the usual misuse of the adjective “Kafkaesque.” Innocent people are found guilty every day, probably, but here the sheer pileup of questionable and suborned witnesses, overlooked evidence, logical impossibilities, holes the size of craters in the prosecution’s case, procedural irregularities—the absence of anything at all linking Oscar Slater to the crime other than the general fact that he was “patently and unmistakably a foreigner“—is breathtakingly one-sided. Here as in a number of the cases Roughead’s barely controlled outrage in the face of injustice, to the point where he becomes an actor in his own story, reveals that he was no mere vicarious bloodshed buff but an idealist and even a crusader. Such a combination of gifts and attributes as Roughead possessed is seldom found in writers of any description, and it is probably safe to say that they have never otherwise been brought together in the practice of that unfairly déclassé genre, true crime.

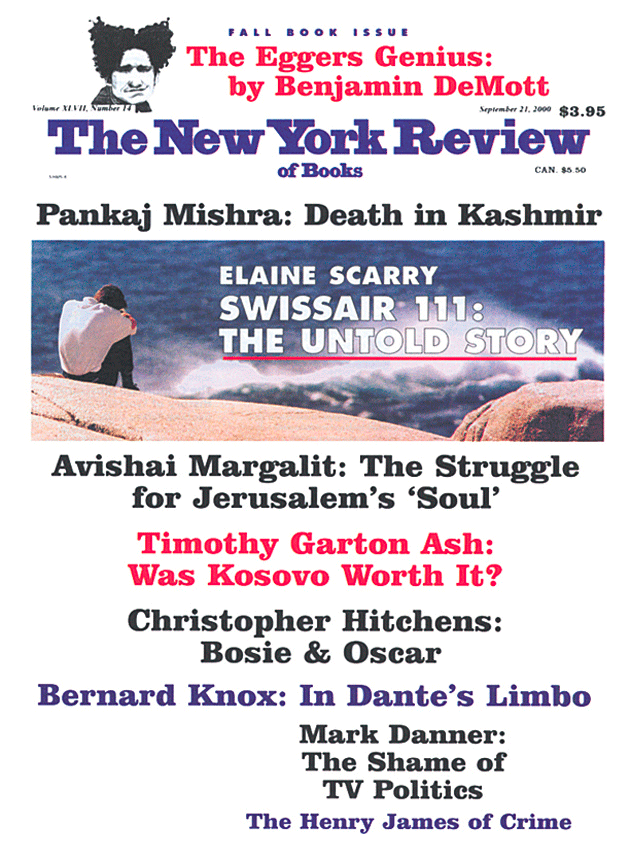

This Issue

September 21, 2000

-

*

First published in 1951, William Roughead’s Classic Crimes is being reissued this fall by New York Review Books. This essay will appear in slightly different form as the introduction. ↩