1.

Hillary Clinton must be throwing a fit. Here she is, a United States senator, rising up at last from the Grand Guignol of her husband’s presidency, eager to be judged on her own merits—and she’s pulled back down into the muck. She is, yet again, not “Hillary,” but one half of “the Clintons,” and the Clintons are getting it right between the eyes. The gradually unfurling narrative of the former president’s pardons of well-connected crooks and swindlers has proved so revolting that even some of the Clintons’ most ardent defenders have finally had it up to their keister. Bob Herbert, the New York Times columnist, recently described the Clintons as “a terminally unethical and vulgar couple” who might well be “led away in handcuffs someday,” and have in any case forfeited all rights to leadership. This is the kind of language one is accustomed to hearing from the Clinton-haters, like former Bush speechwriter Peggy Noonan. Now you hear it from even the stoutest resisters. Clinton-fatigue has suddenly collapsed into Clinton-contempt.

It will, of course, be easier for Mrs. Clinton to pull herself out of the ooze than for Bill, who no longer has the power of the presidency to distract us from his peccadilloes. Mrs. Clinton can use the next six years to erase whatever ill feeling lingers from the previous eight. Look at what a combination of time and unremitting dedication to causes has done for Teddy Kennedy, to whom she is often compared. Mrs. Clinton, whose ability to command attention equals Kennedy’s at the height of his power, and perhaps exceeds it, called a press conference in late February to take on the allegations over the pardons. She was, as she has taught herself to be in such moments, equable, patient, even masterful. But that doesn’t mean she solved the problem. She denied having “any involvement” in the pardons, though both her big brother, Hugh, and her little brother, Tony, had actively canvassed their White House contacts on behalf of friends or clients in need of clemency.

What’s worse, last December she sat in on a meeting which the President held with a Hasidic leader who sought pardons for four members of his community who had been convicted of embezzlement and fraud. This Hasidic community had supported Mrs. Clinton in her Senate campaign by a comically lopsided margin. The four men received their pardon, and federal prosecutors are now examining whether Mrs. Clinton broke the law, presumably by promising lenient treatment in exchange for continued support. The senator is not likely to be led off in handcuffs, not only because it’s hard to imagine her offering any such quid pro quo but also because such transactions are virtually impossible to prove. But people just don’t believe Mrs. Clinton’s sweeping assertion of innocence anymore. This one earned her Slate magazine’s “Whopper of the Week” award.

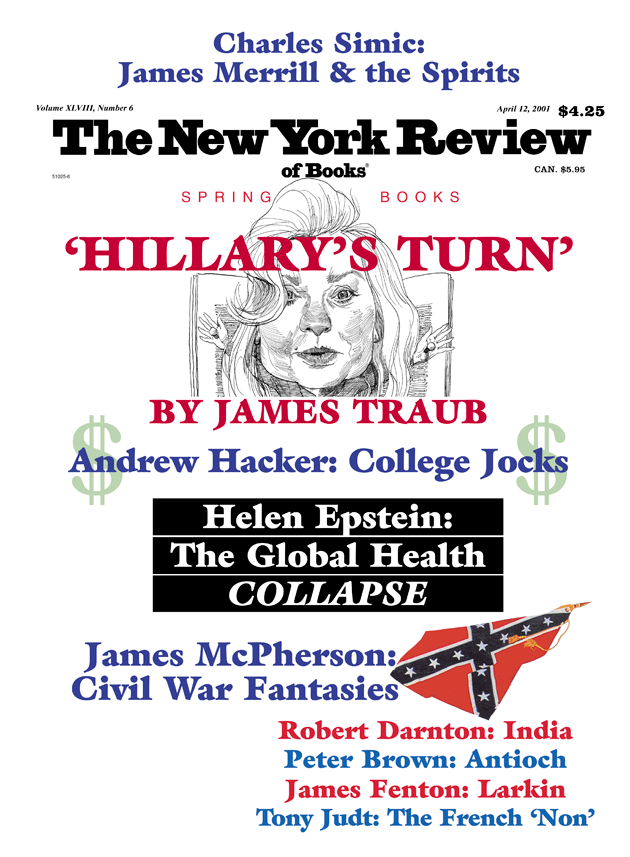

Mrs. Clinton cannot get in the clear, no matter what she does. She has in many ways patterned herself after her hero, Eleanor Roosevelt; but though she may earn as much enmity as Mrs. Roosevelt had in her day, it is almost inconceivable that she will earn anything like the same reverence. While Mrs. Roosevelt was despised by her political foes, Mrs. Clinton has somehow contrived to be disliked, and often intensely so, by people who share her views. This is the great peculiarity of her political career, and it is a mystery with which Michael Tomasky wrestles manfully in Hillary’s Turn, his account of Mrs. Clinton’s Senate campaign.

He does not, however, wrestle it to the ground. The question will remain whether Mrs. Clinton’s gift for inspiring enmity is her fault or ours. To put the question differently, should we try to understand Mrs. Clinton’s larger meaning by delving into her character or into the liberal political culture? I, for one, would love to see someone write a book about her similar to Wayne Koestenbaum’s Jackie Under My Skin, his attempt to mine the meanings we project onto Jackie Kennedy. At the same time, politicians who can’t make their own supporters like them are probably in the wrong line of work. Watching her, you sometimes think: if only she had a sense of humor you could live with her piety. But it seems, alas, that she doesn’t.

Michael Tomasky is a member of the literary subgenre of Rudy Giuliani’s victims. Like the mayor’s two biographers, Andrew Kirtzman and Wayne Barrett, he expected the public’s attention to be riveted by a senatorial contest between Mrs. Clinton and Giuliani, two of the most formidable and easily dislikable politicians ever to run against anyone, much less each other. Giuliani, of course, disobliged an avid press by withdrawing from the race last May, before he even formally entered it. Tomasky and his colleagues in the daily press were left to observe a campaign that was grotesquely distended, generally tedious, and—unlike the contest for president—anti-climactic. Tomasky has written a faithful account of a contest that hardly bears the weight of a faithful account.

Advertisement

Tomasky seems to like Mrs. Clinton more than her most recent biographer, Gail Sheehy does, not to mention her caricaturists on the right, including Peggy Noonan and Barbara Olson, wife of Bush’s solicitor-general and author of Hell to Pay, a masterpiece of unremitting contumely. Sheehy’s Hillary, like Susan Stanton in Joe Klein’s Primary Colors, is a character you wouldn’t want to meet in a dark alley, a policy-wonk version of Xena, Warrior Princess. Tomasky, who writes the “City Politic” column for New York magazine, was braced for that Mrs. Clinton when she came to his office for his one and only private interview, early in the campaign. But when he asked her about her “interests in life outside politics and policy,” she responded with an apparently unrehearsed lit-any of upper-middlebrow hobbies—archaeology and anthropology and classical history and modern art. She also knew the Flintstones theme song, and she clinched the sale when she did the Three Stooges’ finger-snapping routine. “She wasn’t enigmatic or brittle,” Tomasky writes, with undisguised relief. “She had enthusiasms and a playful side.” This is setting the bar pretty low: Mrs. Clinton has turned out to be a human being, rather than a silicon-based life form. But such a conclusion gives a telling picture of her received image.

Hillary Clinton is one of those public figures of whom it is often said, “If you could only see what they’re like in private.” Indeed, we have it on no less an authority than Dick Morris, the disgraced genius of polling and spin, that Mrs. Clinton is “warm and friendly as an individual but relatively rigid as a political figure.” (Morris’s use of his column in The New York Post to stomp all over her during the campaign, despite the friendly feelings he’s expressed about her elsewhere, makes him Tomasky’s principal villain.)

The principal drama of Hillary’s Choice is the laborious effort of this extremely cautious figure, prone to both solemnity and sanctimony, to construct a usable political persona. The press, Tomasky very much included, hunted desperately through Mrs. Clinton’s every public utterance and act for clues to the private self. Tomasky makes the intriguing point that the New York reporters, unlike the ones in Washington, did not view themselves as gatekeepers of national morality, and scarcely ever asked Mrs. Clinton about Filegate, Travelgate, or any of the other gates with which she was perpetually taxed back home; but they peppered her remorselessly with questions designed to “solve the vexing riddle of who she was.”

Part of Mrs. Clinton’s problem was that she was not “ethnic,” meaning not only that she was not Italian or Irish or Jewish or black, but that she lacked the sense of ethnic particularity that for New Yorkers spells authenticity. New York politics, and indeed New York life, is still atavistic this way. You are expected to be tribal; and Mrs. Clinton was, instead, deracinated and bland, just the way New Yorkers imagine Midwesterners to be. She lacked not only an accent but a sense of personal commitments, passions, even preferences. This was why the incident early in the campaign in which she appeared in a Yankees hat and claimed to be a lifelong Yankees fan despite having grown up in Chicago rooting for the Cubs, was such a gaffe. If she was willing to fabricate a primal allegiance to prove that she was a real New Yorker, then she probably didn’t have any real allegiances at all, in which case she certainly wasn’t a New Yorker. (Tomasky points out that Mrs. Clinton actually was a lifelong Yankee fan, but, apparently viewing the incident as too trivial to pursue, she said nothing in her own defense.)

Mrs. Clinton could have responded to the clamor for self-revelation by dropping her “g”s and talkin’ ’bout family calamities, the way Al Gore did. But she didn’t, or perhaps couldn’t. Tomasky records her telling a bus full of frustrated reporters, “‘Who are you?’ and all of that. I don’t know if that is the right question.” Almost despite himself, Tomasky comes to admire her high-mindedness, her refusal to stoop to the kind of therapeutic twaddle that has become the stock-in-trade of the aspiring pol. Tomasky describes Mrs. Clinton as a throwback to an era when “politicians talked more about the social order and less about themselves.” But Mrs. Clinton never talked about anything as grand as the social order, and besides, making the distinction between policy and character, between high and low, is mostly a symptom of not liking politics. Ask yourself: Would Mike Dukakis have made a great president? FDR, to take a counterexample, didn’t have to talk about who he was; you understood just by listening to him.

Advertisement

Not so Mrs. Clinton, who rarely speaks an unpremeditated syllable; somewhere between her consciousness and her lips she has constructed the kind of flash-boiling tank that renders wine mev shulam, or super-kosher, by removing every last trace of impurity. Perhaps this would happen to anybody who’s taken the kind of public pounding that she has. Viewing the solid earth as too dangerous, Mrs. Clinton often dwells instead in the ether of generality and fine sentiment. Here is an excerpt from, of all things, a CNN interview that Gail Sheehy used as an epigram for Hillary’s Choice: “I think that in everyday ways, how you treat your disappointments, and whether you’re able to forgive the pain that others cause you, and, frankly, to acknowledge the pain you cause to others, it’s one of the big challenges we face as we move into this next century.” Goodbye Oprah, hello UN General Assembly.

And yet she won. In the end, Mrs. Clinton found a way of presenting herself to the public. She devoted nearly three hours a day, Tomasky writes, to “rope-line time,” shaking hands with voters, looking them in the eye, asking about local problems and taking mental notes. It was, Tomasky surprisingly argues, “a pivotal, perhaps the pivotal, development in this campaign.” Voters could see the First Lady not as a political adventurer parachuting in from Washington, or an avatar of the Sixties, or the other half of the world’s most powerful couple, but as a dedicated reformer who cared deeply about fixing traffic flow. She neutralized the “carpetbagger” argument by sheer hard work, visiting heavily Republican upstate New York towns dozens of times, facing down the forest of “Go Home to Arkansas” signs with her implacable demeanor. In the end, she won a startling 47 percent of the vote upstate. Voters must have been flattered by her persistence; and, as New York City political pros like to observe, upstate is basically the Midwest, so Mrs. Clinton may have benefited from the sense of cultural fit.

2.

The election also gave New York voters a chance to figure out exactly what it is Mrs. Clinton stands for. Everyone seems to know the answer to this question, but the answers are mutually contradictory. Barbara Olson describes Mrs. Clinton as “a determined, focused leader who rapidly rose to the top ranks of the radical left, and who now seeks to foment revolutionary changes from the uniform of a pink suit.” It’s true that Mrs. Clinton once gave a speech at Wellesley in which she declared that she and her classmates were “searching for more immediate, ecstatic and penetrating modes of living.” It’s also true that she spent one summer taking on Black Panther cases with an Oakland law firm run by self-professed Communists. On the other hand, you’d have to be seriously tone-deaf to Sixties rhetoric to mistake Hillary Clinton for a radical. She was, according to Sheehy, allergic to the romanticizing of outlaw behavior endemic at the time, and even Olson is forced to concede that Hillary supported Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 election. A more plausible case can be made that Mrs. Clinton was, at least at one time, an orthodox liberal and eager social engineer, preoccupied with the language of rights and almost always on the designated left side of divisive issues (though not always; she has long favored the death penalty).

Tomasky tries to reconcile Mrs. Clinton’s conservative temperament and her liberal views by comparing her to a “nineteenth-century woman’s movement reformer,” like Julia Ward Howe or Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It’s a useful analogy, and it captures something of Mrs. Clinton’s resolute moralism and occasionally shrill self-righteousness, which stand in such jarring contrast to her husband’s worldly secularism. At the same time, it’s plain from Tomasky’s careful reporting that New Yorkers following this election heard no more of Carrie Nation than they did of Jane Fonda, or even of Our Lady of the Children’s Defense Fund. During the campaign, Tomasky writes, Mrs. Clinton “was an extremely—at times, maddeningly—cautious candidate who spent her time talking about things like utility rates and upstate technology corridors.” Mrs. Clinton sounded like a “centrist,” but Tomasky’s point is that she wasn’t about to jeopardize her chances by saying anything remotely controversial. As with questions of self-presentation, her goal was to make no mistake, including the mistake of trying to be interesting. Whatever her ideology, she was happy to adopt what she concluded, rightly, was a winning strategy.

What are Mrs. Clinton’s “real” views? It is, in general, a mistake to imagine that a politician’s views are made of the same material as a journalist’s views or a policy intellectual’s views. With the exception of entertaining mavericks like former senator Bob Kerrey, or insurrectionaries like Newt Gingrich, a politician will include in his views a fine calculation of what the market will bear; nobody demonstrated either the virtues or the shortcomings of having one’s ear to the ground better than Bill Clinton did. Mrs. Clinton, for all her high-mindedness, knows when to bury unpopular convictions. Dick Morris describes her as “pragmatic and shrewd”—high praise from him—and says that she served as his back channel even during the Arkansas years. Mrs. Clinton ultimately infuriated her old friend Marian Wright Edelman, the chairman of the Children’s Defense Fund, with her support of the President’s welfare reform plan. At the same time, Mrs. Clinton was too much the rationalist and the earnest policy professional to share her husband’s intuitive feel for the public mood; the 1994 health-insurance reform package, the only true fiasco of the Clinton years, was also the only venture into public policy that Bill Clinton allowed Hillary to run. Perhaps she’s just doctrinaire enough to have a tin ear.

Tomasky has one scoop, and it must be said that while it would have been hot stuff during the campaign, it seems lukewarm in the aftermath. It turns out that there was a tremendous and long-running debate inside the campaign over whether Mrs. Clinton should confront the fact so many voters couldn’t stand her. One side said that Democrats would stay home or even defect to Republican Rick Lazio unless she addressed their antipathy; the other side felt, as Tomasky quotes pollster Mark Penn as saying, “You don’t deal with negatives on trust by saying trust me.” The campaign paid a consultant, Dwight Jewson, to convene focus groups of suburban women, who spoke of Mrs. Clinton with an extraordinary mixture of disgust, fear, condescension, bafflement, and respect. This provoked what Tomasky grandly calls “the wrestling match over the soul of the campaign.” It wasn’t the kind of wrestling match you’d pay money to see; it was too one-sided. Mrs. Clinton let both sides argue until 2:30 one morning, and then came down on Penn’s side. The campaign’s wish to have her address the feelings she aroused was analogous to the press’s wish to have her sound more like a human being; the same response, in fact, would have satisfied both. Mrs. Clinton just kept talking about “the issues,” though, as Tomasky points out, she was scarcely more enlightening on this subject than she was on her innermost nature. Anyway, it worked.

But the question remains: What is it about the Hillary Hatred? I can’t count the number of cosmopolitan, highly professional women who have told me that they loathe Mrs. Clinton. (Tomasky mentions that he and I discussed such reactions at a Clinton event one morning.) Some despised her for staying with her husband, others for taking advantage of her position and then indulging in the kind of cynical self-dealing they would have expected of a conventional politician; they always had good reasons, but the reasons never seemed quite sufficient to their anger.

Tomasky himself takes the sociological view of the question. He speculates that Mrs. Clinton was a victim of her own generation’s “morality of authenticity,” its insistence on purity of motive and its contempt for compromise. Having made their own uneasy “truce with bourgeois convention,” Tomasky writes, baby boomers needed the Clintons to vindicate those Sixties values, and to prove that this generation had not merely recycled their parents lives’ with cooler gear. The Clintons, he believes, were bound to fail by this “narcissistic” standard. As for the less sophisticated and lesswell-off women Jewson interviewed, Tomasky writes that they “were clearly caught in some sort of inner, emotional tug of war over feminism and its legacies.” They expected women to be independent and successful, but also humble and stoical. Mrs. Clinton couldn’t possibly satisfy either group, much less both at once.

If the fault-lies-in-ourselves theory is correct, then we would have to conclude that anybody with Mrs. Clinton’s general lineaments would have fallen into the same trap. Is that so? What about an American version of Cherie Blair, the wife of British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who did not surrender her flourishing career as a lawyer to become either a full-time mother or her husband’s political helpmeet? Cherie Blair is widely admired in England, where, admittedly, expectations of women seem less contradictory than they do here. In any case, Mrs. Blair took the path that feels normal to many professional women; it is Mrs. Clinton who is the outlier. Of course, Mrs. Clinton loved being involved in social policy matters as much as her husband did, and she had good reason to feel that she could accomplish more by joining her career to his than continuing as an activist/ writer/lawyer. But doing so put her on a path to painful compromise that she scarcely could have imagined at the time. In order to satisfy the voting public, Mrs. Clinton felt she had to change her name, change her clothes, change her language, and change her hair—again and again. She had to play a role that she herself must have often found demeaning. The first time I ever saw her was during a speech that Bill gave in the fall of 1991. She had been positioned on the stage, perhaps five feet in front of him and slightly off to the side; and she made all the appropriate facial expressions as Bill delivered his spiel. I couldn’t imagine Eleanor Roosevelt putting herself in the same position.

And so should we say that women have punished Mrs. Clinton because she is ambitious? Maybe some have; but others, themselves every bit as ambitious as she, get riled over the compromises that she made in the name of ambition. This, too, may reflect her critics’ fantasy of purism, as Tomasky claims; maybe we should cut her some slack. But Mrs. Clinton’s own air of pure commitment, her humorless moralism, compounded the problem. Ambitious people who won’t admit to their own ambition get our goat—think of Pat Robertson. And so Mrs. Clinton may get blamed inordinately for indulging in the ordinary devices of politics, like meeting with important constituents seeking a pardon from her husband. She’s a magnet for blame. A psychiatrist once tried to explain Hillary-hating to me by observing that many women couldn’t bring themselves to fault Bill Clinton, a lovable rogue if ever there was one; and so they dumped their wrath instead on the eminently suitable Hillary. Let us leave this vexing problem by saying that Mrs. Clinton suffered from a combination of her choices, her character, her husband, and the projection of our own irreconcilable wishes.

If only the election itself had been as interesting as these insoluble questions. Tomasky’s narrative may be summarized as follows: Mrs. Clinton made several dumb mistakes right out of the gate, including wearing the Yankees cap and kissing Yasser Arafat’s wife, Suha, at an event on the West Bank. Then she righted herself through good advice and stunning self-discipline. Then the tantalizing would-be opponent, Rudy Giuliani, dropped out. Then Rick Lazio, a moderate and thoroughly genial congressman from eastern Long Island, built up a huge campaign war chest and looked like a formidable candidate before turning out to be a dud. Lazio’s campaign was based on the premise that Mrs. Clinton couldn’t be trusted. Once she had blunted this attack by virtue of her decorum and steadfast blandness, Lazio turned out to have absolutely nothing else up his sleeve. In the end, Hillary thrashed the pup, 55–43, a huge margin by New York standards, and especially so with a polarizing figure and “carpetbagger” such as Mrs. Clinton.

What now? Mrs. Clinton is doing her best imitation of a humble junior senator, trotting out legislation to help the local economy and trying not to attract undue attention, which is hard for her to do short of taking a vow of silence. This phase can’t last long. The Democratic Party is in a bad state, with neither an obvious leader nor an obvious direction forward. If Mrs. Clinton steps into the breach, while at the same time forswearing any ambitions to run for president in 2004, she may start winning back some of those disenchanted ex-allies. And then the question of what, if anything, Mrs. Clinton actually believes in will matter greatly.

President Bush’s plan to cut taxes while shrinking the federal government, at least as a percentage of gross national product, has given the Democrats the perfect opportunity to “go back to their base”—by arguing that Bush is redistributing resources from the poor and the middle class to the rich. This is precisely the kind of fight the Democrats should be spoiling for. But if the same “base” pulls the party back to the safe harbor of its old shibboleths, whether on trade or school reform or issues of race and identity, then it may lose much of the ground it gained under Bill Clinton. Alas, the one figure you could trust to deal with this dilemma is Bill Clinton himself. I’m not convinced that Mrs. Clinton has either his dexterity or, Dick Morris notwithstanding, his centrist inclinations. If it turns out that she does, then no one save her sworn enemies will remember why she met with that Hasidic rabbi, or what she knew or didn’t know about her brothers’ entreaties.

This Issue

April 12, 2001