On a summer afternoon in 1964 I went to a neighborhood movie theater to see the Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night. It was less than a year since John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Kennedy’s death, and its aftermath of ceremonial grief and unscheduled violence, had if nothing else given younger observers an inkling of what it meant to be part of an immense audience. We had been brought together in horrified spectatorship, and the sense of shared spectatorship outlasted the horror. The period of private shock and public mourning seemed to go on forever, yet it was only a matter of weeks before the phenomenally swift rise of a pop group from Liverpool became so pervasive a concern that Kennedy seemed already relegated to an archaic period in which the Beatles had not existed. The New York DJs who promised their listeners “all Beatles all the time” were not so much shaping as reflecting an emergence that seemed almost an eruption of collective will. The Beatles had come, as if on occult summons, to drive away darkness and embody public desire on a scale not previously imagined.

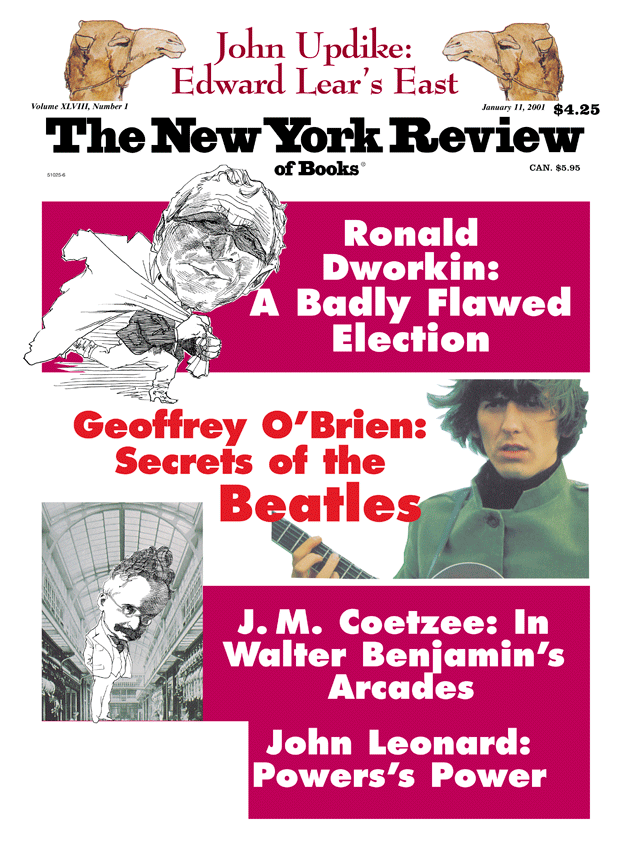

Before the Christmas recess—just as “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was finally breaking through to a US market that had resisted earlier releases by the Beatles—girls in my tenth-grade class began coming to school with Beatles albums and pictures of individual Beatles, discussing in tones appropriate to a secret religion the relative attractions of John or Paul or Ringo or even the underappreciated George. A month or so later the Beatles arrived in New York to appear on The Ed Sullivan Show and were duly ratified as the show business wonder of the age. Everybody liked them, from the Queen of England and The New York Times on down.

Even bystanders with no emotional or generational stake in the Beatles could appreciate the adrenaline rush of computing just how much this particular success story surpassed all previous ones in terms of money and media and market penetration. It was all moving too fast even for the so-called professionals. The Beatles were such a fresh product that those looking for ways to exploit it—from Ed Sullivan to the aging news photographers and press agents who seemed holdovers from the Walter Winchell era—stood revealed as anachronisms as they flanked a group who moved and thought too fast for them.*

And what was the product? Four young men who seemed more alive than their handlers and more knowing than their fans; aware of their own capacity to please more or less everybody, yet apparently savoring among themselves a joke too rich for the general public; professional in so unobtrusive a fashion that it looked like inspired amateurism. The songs had no preambles or buildups: the opening phrase—“Well, she was just seventeen” or “Close your eyes and I’ll kiss you”—was a plunge into movement, a celebration of its own anthemic impetus. Sheer enthusiasm, yet tempered by a suggestion of knowledge held in reserve, a distancing that was cool without malice. When you looked at them they looked back; when they were interviewed, it was the interviewers who ended up on the spot.

That the Beatles excited young girls—mobs of them—made them an unavoidable subject of interest for young boys, even if the boys might have preferred more familiar local products like Dion and the Belmonts or Freddy Cannon to a group that was foreign and long-haired and too cute not to be a little androgynous. The near-riots that accompanied the Beatles’ arrival in New York, bringing about something like martial law in the vicinity of the Warwick Hotel, were an epic demonstration of nascent female desire. The spectacle was not tender but warlike. The oscillation between glassy-eyed entrancement and emotional explosion, the screams that sounded like chants and bouts of weeping that were like acts of aggression, the aura of impending upheaval that promised the breaking down of doors and the shattering of glass: this was love that could tear apart its object.

I dols who needed to be protected under armed guard from their own worshippers acquired even greater fascination, especially when they carried themselves with such cool comic grace. To become involved with the Beatles, even as a fan among millions of others, carried with it the possibility of meddling with ferocious energies. Spectatorship here became participation. There were no longer to be any bystanders, only sharers. We were all going to give way to the temptation not just to gawk at the girl in Ed Sullivan’s audience—the one who repeatedly bounced straight up out of her seat during “All My Loving” as if pulled by a radar-controlled anti-gravity device—but to become her.

I emerged from A Hard Day’s Night as from a conversion experience. Having walked into the theater as a solitary observer with more or less random musical tastes, I came out as a member of a generation, sharing a common repertoire with a sea of contemporaries. The four albums already released by the Beatles would soon be known down to every hesitation, every intake of breath; even the moments of flawed pitch and vocal exhaustion could be savored as part of what amounted to an emotional continuum, an almost embarrassingly comforting sonic environment summed up, naturally, in a Beatles lyric:

Advertisement

There’s a place

Where I can go

When I feel low…

And it’s my mind,

And there’s no time.

Listening to Beatles records turned out to be an excellent cure for too much thinking. It was even better that the sense of refreshment was shared by so many others; the world became, with very little effort, a more companionable place. Effortlessness—the effortlessness of, say, the Beatles leaping with goofy freedom around a meadow in A Hard Day’s Night—began to seem a fundamental value. That’s what they were there for: to have fun, and allow us to watch them having it. That this was a myth—that even A Hard Day’s Night, with its evocation of the impossible pressure and isolation of the Beatles as hostages of their fame, acknowledged it as a myth—mattered, curiously, not at all. The converted choose the leap into faith over rational argument. It was enough to believe that they were taking over the world on our behalf.

A few weeks later, at dusk in a suburban park, I sat with old friends as one of our number, a girl who had learned guitar in emulation of Joan Baez, led us in song. She had never found much of an audience for her folksinging, but she won our enthusiastic admiration for having mastered the chord changes of all the songs in A Hard Day’s Night. We sang for hours. If we had sung together before the songs had probably been those of Woody Guthrie or the New Lost City Ramblers, mementos of a legendary folk past. This time there was the altogether different sensation of participating in a new venture, a world-changing enterprise that indiscriminately mingled aesthetic, social, and sexual possibilities.

An illusion of intimacy, of companionship, made the Beatles characters in everyone’s private drama. We thought we knew them, or more precisely, and eerily, thought that they knew us. We imagined a give-and-take of communication between the singers in their sealed-off dome and the rest of us listening in on their every thought and musical reverie. It is hard to remember now how familiarly people came to speak of the Beatles toward the end of the Sixties, as if they were close associates whose reactions and shifts of thought could be gauged intuitively. They were the invisible guests at the party, or the relatives whose momentary absence provided an occasion to dissect their temperament and proclivities.

That intimacy owed everything to an intimate knowledge of every record they had made, every facial variation gleaned from movies and countless photographs. The knowledge was not necessarily sought; it was merely unavoidable. The knowledge became complex when the Beatles’ rapid public evolution (they were after all releasing an album every six months or so, laying down tracks in a couple of weeks in between the tours and the interviews and the press conferences) turned their cozily monolithic identity into a maze of alternate personas. Which John were we talking about, which Paul? Each song had its own personality, further elaborated or distorted by each of its listeners. Many came to feel that the Beatles enjoyed some kind of privileged wisdom—the evidence was their capacity to extend their impossible string of successes while continuing to find new styles, new techniques, new personalities—but what exactly might it consist of? The songs were bulletins, necessarily cryptic, always surprising, from within their hermetic dome at the center of the world, the seat of cultural power.

Outside the dome, millions of internalized Johns and Pauls and Georges and Ringos stalked the globe. What had at first seemed a harmonious surface dissolved gradually into its components, to reveal a chaos of conflicting impulses. Then, all too often, came the recriminations, the absurd discussions of what the Beatles ought to do with their money or how they had failed to make proper use of their potential political influence, as if they owed a debt for having been placed in a position of odd and untenable centrality. All that energy, all that authority: toward what end might it not have been harnessed?

At the end of the seven-year run, after the group finally broke up, the fragments of those songs and images would continue to intersect with the scenes of one’s own life, so that the miseries of high school love were permanently imbued with the strains of “No Reply” and “I’m a Loser,” and a hundred varieties of psychic fracturing acquired a common soundtrack stitched together from “She Said She Said” (“I know what it’s like to be dead”) or the tornado-like crescendo in the middle of “A Day in the Life.” Only that unnaturally close identification could account for the way in which the breakup of the Beatles functioned as a token for every frustrated wish or curdled aspiration of the era. Their seven fat years went from a point where everything was possible—haircuts, love affairs, initiatives toward world peace—to a point where only silence remained open for exploration.

Advertisement

All of this long since settled into material for biographies and made-for-TV biopics. Even as the newly released CD of their number one hits breaks all previous sales records, the number of books on the Beatles begins to approach the plateau where Jesus, Shakespeare, Lincoln, and Napoleon enjoy their bibliographic afterlife. If The Beatles Anthology has any claim, it is as “The Beatles’ Own Story,” an oral history patched together from past and present interviews, with the ghost of John Lennon sitting in for an impossible reunion at which all the old anecdotes are told one more time, and occasion is provided for a last word in edgewise about everything from LSD and the Maharishi to Allen Klein and the corporate misfortunes of Apple.

The book, which reads something like a Rolling Stone interview that unaccountably goes on for hundreds of pages, is heavy enough to challenge the carrying capacity of some coffee tables and is spread over multicolored page layouts that seem like dutifully hard-to-read tributes to the golden age of psychedelia. It is the final installment of a protracted multimedia project whose most interesting component was a six-CD compilation of outtakes, alternates, and rarities released under the same title in 1995.

Those rarities—from a crude tape of McCartney, Lennon, and Harrison performing Buddy Holly’s “That’ll Be the Day” in Liverpool in 1958 to John Lennon’s original 1968 recording of “Across the Universe” without Phil Spector’s subsequently added orchestral excrescences—were revealing and often moving, and left no question at all that the Beatles were no mirage. Indeed, even the most minor differences in some of the alternate versions served the valuable function of making audible again songs whose impact had worn away through overexposure. In the print-version Anthology, the Beatles are limited to words, words whose frequent banality and inadequacy only increase one’s admiration for the expressiveness of their art. People who can make things like With the Beatles or Rubber Soul or The White Album should not really be required also to comment on what they have done.

The most interesting words come early. Before Love Me Do and Beatlemania and the first American tour, the Beatles actually lived in the same world as the rest of us, and it is their memories of that world—from Liverpool to Hamburg to the dance clubs of northern England—that are the most suggestive. The earliest memories are most often of a generalized boredom and sense of deprivation. A postwar Liverpool barely out of the rationing card era, with bombsites for parks (Paul recalls “going down the bombie” to play) and not much in the way of excitement, figures mostly as the blank backdrop against which movies and music (almost exclusively American) could make themselves felt all the more powerfully. “We were just desperate to get anything,” George remarks. “Whatever film came out, we’d try to see it. Whatever record was being played, we’d try to listen to, because there was very little of anything…. You couldn’t even get a cup of sugar, let alone a rock’n’roll record.”

Fitfully a secret history of childhood music takes form: Paul listening to his pianist father play “Lullaby of the Leaves” and “Stairway to Paradise,” George discovering Hoagy Carmichael songs and Josh White’s “One Meatball,” and Ringo (the most unassuming and therefore often the most eloquent speaker here) recalling his moment of illumination:

My first musical memory was when I was about eight: Gene Autry singing “South of the Border.” That was the first time I really got shivers down my backbone, as they say. He had his three compadres singing, “Ai, ai, ai, ai,” and it was just a thrill to me. Gene Autry has been my hero ever since.

Only John—indifferent to folk (“college students with big scarfs and a pint of beer in their hands singing in la-di-da voices”) and jazz (“it’s always the same, and all they do is drink pints of beer”)—seems to have reserved his enthusiasm until the advent of Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard: “It was Elvis who really got me out of Liverpool. Once I heard it and got into it, that was life, there was no other thing.” If one can imagine Paul playing piano for local weddings and dances, George driving a bus like his old man, and Ringo perhaps falling into the life of crime his teenage gang exploits seemed to promise, it is inconceivable that John could have settled into any of the choices he was being offered in his youth.

None of them ever did much except prepare themselves to be the Beatles. Their youths were devoid of incident (at least of incident that anyone cared to write into the record) and largely of education. John, the eldest, had a bit of art school training, but for all of them real education consisted more of repeated exposure to Carl Perkins, Chuck Berry, and Frank Tashlin’s Cinemascope rock’n’roll extravaganza The Girl Can’t Help It. On the British side, they steeped themselves in the surreal BBC radio comedy The Goon Show—echoes of Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers’s non sequiturs are an abiding presence in their work—and in the skiffle band craze of the late Fifties (a renewal of old-fashioned jug band styles) they found a point of entry into the world of actual bands and actual gigs.

“I would often sag off school for the afternoon,” writes Paul, “and John would get off art college, and we would sit down with our two guitars and plonk away.” Along with the younger George, they formed a band that played skiffle, country, and rock, and played local dances, and after some changes in personnel officially became, around 1960, the Beatles, in allusion to the “beat music” that was England’s term for what was left of a rock’n’roll at that point almost moribund. Hard up for jobs, they found themselves in Hamburg, in a series of Reeperbahn beer joints, and by their own account were pretty much forced to become adequate musicians by the discipline of eight-hour sets and demanding, unruly audiences. Amid the amiable chaos of whores, gangsters, and endless amphetamine-fueled jamming—“it was pretty vicious,” remarks Ringo, who joined the group during this period, “but on the other hand the hookers loved us”—they transformed themselves into an anarchic rock band, “wild men in leather suits.” Back in the UK they blew away the local competition: “There were all these acts going ‘dum de dum’ and suddenly we’d come on, jumping and stomping,” in George’s account. “In those days, when we were rocking on, becoming popular in the little clubs where there was no big deal about The Beatles, it was fun.”

Once the group gets back to England, the days of “sagging off” and “plonking away” are numbered. As their ascent swiftly takes shape—within a year of a Decca executive dismissing them with the comment that “guitar groups are on the way out” they have dropped the “wild man” act and are already awash in Beatlemania—the reminiscences have less and less to do with anything other than the day-to-day business of recording and performing. Once within the universe of EMI, life becomes something of a controlled experiment, with the Beatles subjected to unfamiliar sorts of corporate oversight:

PAUL: …We weren’t even allowed into the control room, then. It was Us and Them. They had white shirts and ties in the control room, they were grown-ups. In the corridors and back rooms there were guys in full-length lab coats, maintenance men and engineers, and then there was us, the tradesmen…. We gradually became the workmen who took over the factory.

If they took over, though, it was at the cost of working at a killing pace, churning out songs, touring and making public appearances as instructed, keeping the merchandise coming. It can of course be wondered whether this forced production didn’t have a positive effect on their work, simply because the work they were then turning out—everything from “Love Me Do” and “Please Please Me” to Rubber Soul was produced virtually without a break from performing or recording—could hardly be improved.

It is the paradox of such a life that it precludes the sort of experience on which art usually nurtures itself. The latter-day reminiscences evoke the crew members on a prolonged interstellar flight, thrown back on each other and on their increasingly abstract memories of Earth, and livening the journey with whatever drugs or therapies promise something like the terrestrial environment they have left behind. In this context marijuana and LSD are not passing episodes but central events, the true subject matter of the later Beatles records. In the inner storms of the bubble world, dreams and private portents take the place of the comings and goings of a street life that has become remote.

The isolation becomes glaring in, say, Paul’s recollections of 1967: “I’ve got memories of bombing around London to all the clubs and the shops…. It always seemed to be sunny and we wore the far-out clothes and the far-out little sunglasses. The rest of it was just music.” One can be sure that the “bombing around” took place within a well-protected perimeter. It is around this time that we find the Beatles pondering the possibility of buying a Greek island in order to build four separate residences linked by tunnels to a central dome, like something out of Dr. No or Modesty Blaise, with John commenting blithely that “I’m not worried about the political situation in Greece, as long as it doesn’t affect us. I don’t care if the government is all fascist, or communist…. They’re all as bad as here.”

The conviction grows that the Beatles are in no better position than anyone else to get a clear view of their own career. “The moral of the story,” says George, “is that if you accept the high points you’re going to have to go through the lows…. So, basically, it’s all good.” They know what it was to have been a Beatle, but not really—or only by inference—what it all looked like to everybody else. This leads to odd distortions in tone, as if after all they had not really grasped the singularity of their fate. From inside the rocket was not necessarily the best vantage point for charting its trajectory.

Paul’s comments on how certain famous songs actually got to be written are amiably vague: “‘Oh, you can drive my car.’ What is it? What’s he doing? Is he offering a job as a chauffeur, or what? And then it became much more ambiguous, which we liked.” As much in the dark as the rest of us as to the ultimate significance of what they were doing, the Beatles were all the more free to follow their usually impeccable instincts. So if John Lennon chose to describe “Rain” as “a song I wrote about people moaning about the weather all the time,” and Paul sees the lyrics of “A Day in the Life” as “a little poetic jumble that sounded nice,” it confirms the inadvisability of seeking enlightenment other than by just listening to the records. (John, again: “What does it really mean, ‘I am the eggman’? It could have been the pudding basin, for all I care.”) The band doesn’t know, they just write them.

In the end it was not the music that wore out but the drama, the personalities, the weight of expectation and identity. By the time the Beatles felt obliged to make exhortations like “all you need is love” and “you know it’s gonna be all right,” it was already time to bail out. How nice it would be to clear away the mass of history and personal association and just hear the records for the notes and words. Sometimes it’s necessary to wait twenty years to be able to hear it again, the formal beauty that begins as far back as “Ask Me Why” and “There’s a Place” and is sustained for years without ever settling into formula. Nothing really explains how or why musicians who spent years jamming on “Be Bop a Lula” and “Long Tall Sally” turned to writing songs like “Not a Second Time” and “If I Fell” and “Things We Said Today,” so altogether different in structure and harmony. Before the addition of all the sitars and tape loops and symphony orchestras, before the lyrical turn toward eggmen and floating downstream, Lennon and McCartney (and, on occasion, Harrison) were already making musical objects of such elegant simplicity, such unhectoring emotional force, that if they had quit after Help! (their last “conventional” album) the work would still persist.

Paul McCartney recollects that when the Beatles heard the first playbacks at EMI it was the first time they’d really heard what they sounded like: “Oh, that sounds just like a record! Let’s do this again and again and again!” The workmen taking over the factory were also the children taking over the playroom, determined to find effects that no one had thought of pulling out of the drawer before. They went from being performers to being songwriters, but didn’t make the final leap until they became makers of records. Beyond all echoes of yesterday’s mythologized excitement, the records—whether “The Night Before” or “Drive My Car” or “I’m Only Sleeping” or any of the dozens of others—lose nothing of a beauty so singular it might almost be called underrated.

This Issue

January 11, 2001

-

*

Or so it seemed at the time. The anachronisms worried about it, of course, all the way to the bank, while the Beatles ultimately did their own computing to figure out just how badly they had been shortchanged by the industry pros. ↩