The American poet and critic Randall Jarrell worked as acting literary editor of The Nation from the spring of 1946 to the spring of 1947. One of the several eminent writers from whom Jarrell solicited book reviews was the English poet and critic William Empson, author of Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), Some Versions of Pastoral (1935), and many later books and essays. Empson taught in Japan and China during the Thirties, but returned to England in 1939, and worked for the BBC throughout World War II. Empson reviewed four books for Jarrell and The Nation, among them the first English translation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis (December 7, 1946) and the Selected Writings of Dylan Thomas (February 22, 1947). Jarrell then sent Empson Stuart Gilbert’s translation of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit and The Flies, the French thinker’s first plays to be published in English. In 1947 Empson and his family returned to China, where he resumed his post at Peking National University; he wrote to Jarrell that the book “arrived just as we were getting on the boat.”

Empson reviewed Sartre’s plays nevertheless, sending, from Hong Kong, a typescript with a cover letter dated May 2, 1947. By the time the review arrived in New York, Jarrell was no longer in charge of the book review section, since the literary editor, Margaret Marshall, had returned from her sabbatical. The Nation and Marshall chose not to print the review—perhaps because it had arrived too late, perhaps because of the negative tone it took toward Sartre (himself a Nation contributor), perhaps because it simply got misplaced. (Empson wrote no further prose for The Nation.) This review, and its associated correspondence, along with other letters from Jarrell’s tenure, were found in Marshall’s Nation files, now in Yale’s Beinecke Library.

The review appears here in print for the first time. Empson’s review draws on his earlier interests in Auden, and in myths of sacrifice. It looks forward, too, to the arguments against Christianity he would pursue in his later prose, especially in Milton’s God (1961).

—Stephen Burt

The flurry in France over existentialism deserves respect as a reaction to the German occupation and the ugly nonsense talked by Vichy politicians; it is a philosophy of a psychological method for keeping your self-respect when impotent and surrounded by evil. But so far as I can see it would not deserve respect under any other circumstances; because where there is any prospect of making things better by combined action existentialism would not encourage people to do it. The intellectual claims of the theory need not I think be worried about; it seems to be deeply confused. But the way it has been used by recent French writers to express a general way of feeling produced by the disasters of the country is certainly of great interest; it should be interesting too to see how the thing can be developed, or how they can get out of it.

The play about hell (No Exit), in which there are only three characters and they are to torment one another forever, gets its effect I think from a simple contradiction. There would be no point in such a play unless it implied that life on earth is somehow like this; and yet the whole plausibility of the action, let alone the stage effectiveness of the appeal to our curiosity, depends on making life in hell quite different from life on earth. The play manages to imply that (even on earth) effort is useless and that sufferings due to weakness of temperament are inescapable; and it can only do this by tricking us into a false generalization, so that we imagine the world is like hell even while we are enjoying the difference. This sort of fallacy is generally used in dramatic treatment of the problem of free will, and does not prevent the play from being impressive; and no doubt it is true as well as a frightful record of what some people were feeling in occupied France.

The version of the Orestes story (The Flies) is philosophically more ambitious in that it tries to deal with a moral problem on earth where there is room for decisions. A dynastic blood feud however is not really very close to contemporary problems; and if the classical Greeks, who presumably knew more about it than we do, could accept an ending of reconciliation I do not quite see what new reasons M. Sartre has to tell them they were wrong. If we are to look at the problem freshly, I should say that Orestes was right to kill Aegisthus, who was in any case opposing him by force, but ought not to have killed his own mother, who would have no power to hurt him after Aegisthus was dead. The tortures of remorse seem to have been all about the mother, and need not have been incurred. In short the idea set on foot by Lessing, that the myth is about an intolerable but inescapable conflict between two absolute duties, does not seem to me true. And in any case, whether the Greeks believed or not that it was the duty of Orestes to kill his mother, I cannot gather that M. Sartre has considered the question at all. His characters do not make plans or accept duties; they simply feel, with great emphasis, first one thing and then another. At the end of the play Orestes, in a long speech to the people of Argos which apparently prevents them from tearing him to pieces, says that he killed for their sakes and has taken upon himself their guilt but will not be their king. They must try to reshape their lives for themselves, he says, and he tells them the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin before leaving them “for ever” and taking with him the Furies. I read the first two acts with growing admiration and the final third act with disappointment and distaste. I am not quite sure why.

Advertisement

No doubt the enlightened modern audience is expected to feel that this is the only proper end. Kings are a bad thing, and the people of Argos ought to develop their own democracy. Besides, there could be an obscure parallel with De Gaulle or some such figure, who ought to free France by force but not become a dictator afterward. This group of feelings was a lucky convenience for the playwright. But an existentialist hero is much too prone to walk away from a situation, free in spite of having been betrayed. The idea that he has no public responsibilities is not an attractive thing in itself. And the claim that he killed his mother for the sake of the people of Argos seems to be a mere piece of opportunist lying; excusable no doubt as an escape from being lynched, but not enough to end a play with a glow of admiration. The play makes clear that he did it because he was goaded on by his sister, who despised him for not wanting to gratify her hatreds.

One might think that the trouble with the existentialist view of life is that it is too mean, too convinced that betrayal is to be expected. The objection here is against its rosy trustfulness toward its own type of a hero. He has only to commit his private crime and this will in some magical way release his neighbors, who are also of course potential criminals, so he can very easily claim he did it for their sakes. The scapegoat idea is a very important one; maybe it goes to the roots of human thought; but you can’t simply trot it out as a happy ending. And for that matter it would justify Hitler as easily as anyone else.

What might be called the atmosphere of Argos is the best part of the play, and I suppose would come out very strongly in performance. The people are suffering from an overwhelming sense of guilt, which is applied to their own affairs but is originally due to the crime of their rulers. From this Aegisthus draws his power; he is leader and inventor of the ceremonies that rub in the sense of guilt; he identifies them in public with morality, and in private says that though he feels no guilt himself for the murder of Agamemnon he keeps up this mummery to maintain social order. It is a direct and savage parody, in fact, of the attitude of Pétain toward Vichy France. (Unlike No Exit, the play was not acted under the German occupation.) Electra, before she has Aegisthus killed, tries to exorcise this public neurosis by interrupting a guilt ceremony with a speech and dance in favor of innocent happiness, and would have succeeded if Zeus himself had not sent a portent to frighten people into guilt again. The belief that God not only agrees with Pétain but descends from heaven to plot with him is I suppose important for the theoretical background, because it makes clear that the free existentialist hero is really alone in the universe, with Nature and morality against him as well as the State; he is Byronic. But it seems to me that Electra’s plan would have failed anyway, without this miracle. And to make the failure depend on the miracle weakens the motivation; the disasters which follow are not due to some cause in the nature of things but only to an individual act of divine spite. One might indeed fancy it as spite on the part of the author; he can only see the thing as a personal betrayal.

Advertisement

The theme of betrayal indeed is prominent in the play and causes the chief departure from the old story. Electra here after goading Orestes into the murders turns round and says that she never wanted them; she only had fancies; she hates him for doing it; she will escape the Furies by repenting. All this emphasizes the more manly attitude of Orestes, who refuses to repent because an existentialist hero is free and in some way above right and wrong. Taken alone it gives one nothing to complain about. But all the women in both plays are positively nauseating characters, and this begins to look like bias. It makes one less willing to give a big hand to Orestes when he walks off. One must not complain because the atmosphere of the plays is stifling; no doubt the atmosphere of France was stifling. But I remember a harsh article about the French which said that the women did better than the men under the nightmarish conditions of occupation, and that the men resented it. Be this as it may, and granting that there is a great deal to be said against women at any time, I feel that the animus against them is a neurotic side of M. Sartre. In any case, for a long time now, the French have been famous for shouting out “Nous sommes trahi” as soon as any difficulty arose. When they found that they had really been traheed in a big way they would naturally give it full value. One can sympathize with this without feeling that betrayal is really such a regular and fundamental feature of the human scene as it appears here.

A review of M. Sartre ought to try to distinguish his position from that of existentialism in general. In any case it would be a mistake to sniff suspiciously at the tradition now given that name as if it was very odd and new. The central phrase of Orestes in this play, “Human life begins on the far side of despair,” is very much in the mood of T.S. Eliot and his disciples twenty years ago. I remember I wrote a poem on this topic, with much seriousness, and then was disconcerted to find that it seemed Ninety-ish rather than in the prevailing mode. And I suppose, looking back, that the really wonderful effect of originality with which W.H. Auden burst on the English-speaking scene, around 1930, was partly due to his having read Kafka and so forth in German. Existentialism, in short (it is usually dated back to Kierkegaard in the middle of the last century), has been seeping into English literature steadily though deviously. The Kierkegaard theology of crisis, which I understand says that you are most likely to be in mortal sin when you feel most sure that you are in the right, is a good thing to have a little of; it is the regal solvent against complacency. The trouble if you take it seriously, I think, is that it amounts to erecting your neuroses into a religion; and this tends only to be done by people who have got enough neuroses already. Perhaps the main interest of the recent French development is that it has taken this very apolitical doctrine and tried to apply it to politics. But I think W.H. Auden, without claiming for himself the label of existentialism, was doing that before.

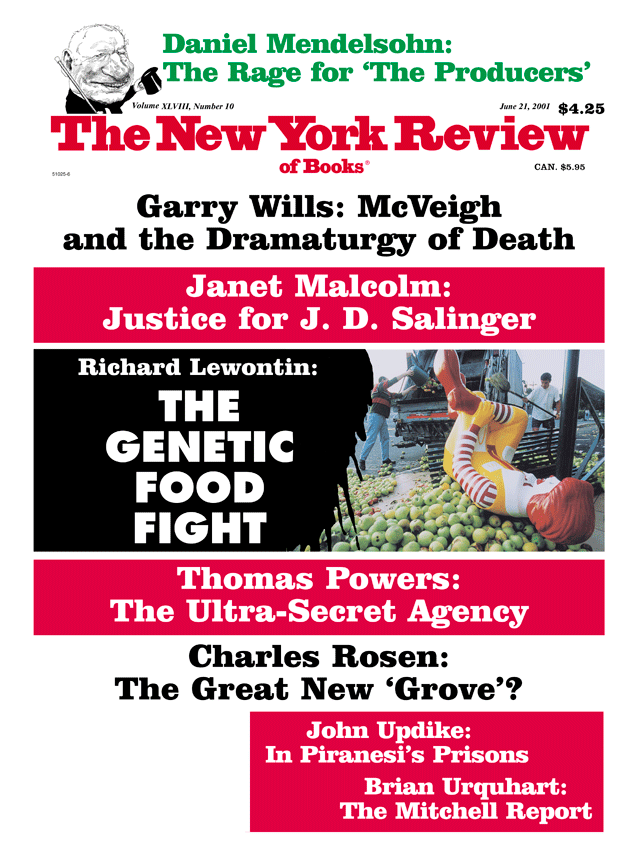

This Issue

June 21, 2001