In the late 1970s I was asked to judge a small but interesting prize, the Prudence Farmer Award, which was given to the best poem that had appeared, that year, in the New Statesman. The best poems that year seemed to me to have been written by two poets, Craig Raine and Christopher Reid, and I divided the award between them. Raine’s poem was called “A Martian Sends a Postcard Home”: it presented human life as seen through the misunderstanding eyes of an alien. Here for instance is a description of a telephone:

In homes, a haunted apparatus sleeps,

that snores when you pick it up.

If the ghost cries, they carry it

to their lips and soothe it to sleep

with sounds. And yet, they wake it up

deliberately, by tickling with a finger.

The last image only works now, of course, for someone familiar with the dial phone.

Reid’s poem was called “Baldanders.” Here is how it goes:

Pity the poor weightlifter

alone on his catasta,

who carries his pregnant belly

in the hammock of his leotard

like a melon wedged in a shopping bag…

A volatile prima donna,

he flaps his fingernails dry,

then—squat as an armchair—

gropes about the floor

for inspiration, and finds it there.

His Japanese muscularity

resolves to domestic parody.

Glazed, like a mantelpiece frog,

he strains to become

the World Champion (somebody, answer it!)

Human Telephone.

The “catasta” on which the weightlifter stands is a platform from which slaves were sold. The mysterious title “Baldanders,” or in English “Soondifferent,” comes from Johann Grimmelshausen’s seventeenth-century novel of the Thirty Years’ War, Simplicius Simplicissimus, and refers to a statue the hero finds which gives him “a recipe for conversing with lifeless objects and, as if for fun, changes into about a dozen different shapes, but always remains its own true Soondifferent self.”* The weightlifter, in the course of a short poem, has been slave, pregnant woman, prima donna, frog, and sumo wrestler before his triumphant transformation into the telephone, and yet, like Baldanders, he has always remained true to his own self. Like Raine’s poem, “Baldanders” revels in the extra-vivid presentation of the familiar. But it comes with its own teasing obscurities, to add to the interest.

In my report on the award, I took pleasure in claiming that the two poets were leading members of the Martian School, and that this school was the one of the most significant of the time. My invention stuck; Raine and Reid have been patiently going along with it ever since, and we find in Charles Simic’s introduction to the new collection of Reid’s poems, his first American collection, that Reid was “the cofounder of the so-called Martian School in the 1970s, a poetic movement notorious for verse that seemed to consist of nothing else but a string of startling images intended to shock the unsuspecting readers.” This is a little harsh. Neither the original “Martian” nor “Baldanders” (the two poems, coincidentally, enjoy a double-page spread together in Paul Keegan’s recent New Penguin Book of English Verse) contains anything at all shocking. The intention was rather to delight. What startled, when it did, was the accuracy of the imagery.

Anyway I was fibbing: there was no Martian School. There were two poets, friends, whose aesthetic somewhat overlapped, and whose careers have since been similar (they successively were editors of the Faber poetry list) but whose personalities were always quite different. Raine was more emotional, keener on the intimate detail, avid for the larger subjects. Reid was at the outset averse to self-revelation. He was a creator of amusing, beautiful objects. Simic says: “To make us think, Reid makes us laugh first.” He certainly makes us smile. In a poem called “Latin American,” about a trashy cocktail bar combo, we get:

Tropical humours!

The old untamed romance!

This piano is a holster for music.

Microphones hide

in a jungle of pinguid rubberplants.

I thrill to the shush of gourds,

that coconut clopping

and our prestidigitant gigolo,

with his hair brushed like a new LP

and one toe-cap hopping.

The piano as holster and the hair brushed like a new LP should amuse us with their accuracy. They are the kind of images that were taken as typically Martian—flashy and far-fetched is how the detractors would have put it. (The new school acquired both imitators and detractors, and it was interesting to see that sometimes the same person could be both an imitator and a detractor.)

For his third collection, after Arcadia (1979) and Pea Soup (1982), Reid invented an author whom he proceeded to impersonate. The volume (most of which is included in Simic’s selection) was called Katerina Brac (1985). Author and publisher (Raine was the editor of this book) contemplated hoaxing the public, and only later revealing that the supposed Eastern European poet was Reid’s invention. But they stopped just short of doing so. Here is the blurb of the collection as it originally appeared (it was composed by Reid):

Advertisement

The testimony of Katerina Brac may strike readers as typical of the artist under pressure, but the way in which this still too little-known poet addresses her situation remains startlingly individual. In presenting a selection of her work, Christopher Reid demonstrates his awareness both of the translator’s special responsibilities, and of the paradox whereby a poet must become the creation of his or her translator.

In other words, look closely and Katerina is fictional.

The poems were composed in two weeks. They represented, for the poet, a holiday from his own style, and perhaps an act of artistic trespass. For it was commonly held, before the various liberations of 1989, that the poets who lived under the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe had, through their sufferings, acquired a unique status and insight. How would it be possible for one to impersonate such a poet, without suffering as she, presumably, had? By what presumption might one imitate a writer “under pressure”?

The answer is of course that fiction writers do this all the time, and there is no reason for the poet to suppose his imagination to be inferior for the task. The poems in Katerina Brac, as I remember, puzzled some readers. They were not like a hoax, or a parody, although they copied a manner with which their readers would have been familiar through a series called Penguin Modern European Poets: they read like translations. And this too involved them in a formal limitation: in addition to renouncing the pleasures of the supersimile for which he and Raine had become well known, Reid, who is an expert at formal verse gently modified (sonnets that come light out of the oven, sestinas that do not sit heavily on the stomach), was going to have to do without meter and rhyme. At most there would be a suggestion that in another language this might have rhymed, scanned, been more tightly knit.

The poems come to us without ulterior motive. They have no designs upon us. Here is the one I take to be the best of them. It is called “An Angel”:

An angel flew by

and the electricity dimmed.

It was like a soft jolt

to the whole of being.

I raised my eyes from the poems

that lay on the kitchen table,

the work of a friend, now dead.

It should not have mattered.

As the light glowed again,

I ought to have continued reading,

but that single pause

terrified me.

We say of the old

that they tremble on the brink.

I found that I was trembling.

Perhaps the black country nights

encourage superstition.

I remembered the angels

that had visited people I knew,

not hurrying past them

and merely stirring the air,

but descending with the all-inclusive

wingspan of annunciation

to obliterate them totally—

and I rose to my feet.

That one brief indecision

of the electric light

in a night of solitude

showed me how weak I was.

The poems on the table

lay where I had left them,

not knowing they had been abandoned.

Two collections have followed. The title poem of In the Echoey Tunnel (1991) offers a wonderful short description of a child reveling in the acoustics of a gloomy tiled space, as it were an underpass, before the disappointment of being “dragged back to daylight.” It seems to stand for something, although no pointers are given to suggest what that something might be. To me (but I do not say that this was Reid’s intention) it evokes a time of early life in which all our aesthetic productions—in this case, acts of squealing and stamping feet, to display the echo to best advantage—seem to us unquestionably wonderful and destined for praise. Then we are dragged away from this blessed place with its perfect acoustics. We never find it again.

“Survival: A Patchwork,” Reid’s most substantial poem, is a tribute to his wife in her recovery from chemotherapy—a work paradoxically both intimate and reticent, the more moving for its uncharacteristic offering of glimpses of the author’s private life. It gains its effect by process of accumulation, and is consequently hard to quote from. Generally speaking, reticence in a poet may be as crippling a fault as a too easy outspokenness. But it is any poet’s task to address the individual convincingly as an individual, while at the same time engaging him as a member of a class (the reader). When in private life we discover that what we had imagined to have been confided in us and us alone was in fact shared with all our acquaintance, we feel cheated and resentful. But what in private life is a fault becomes, for the poet of intimate experience, a prime duty: to confide and yet to make universal.

Advertisement

For some poets the issue does not arise. Nobody, I suppose, felt cheated by Allen Ginsberg in this way, either in private life or in the poetry. Because there was no private domain to speak of. Everything, in life, on the page, was for the public, for the vast collective readership, and we feel as if we are being addressed as part of a vast collective (which in itself can be exciting). The poetic antitype here would be Elizabeth Bishop: we would be shocked to find her addressing us as anything other than individuals of the highest integrity, but of course this depends on an act of faith. When Bishop offers us an intimate poem such as “The Shampoo,” she is not to know whether she is squandering her privacy.

I mention Bishop because it might be doubted by an American reader that her influence would have spread far or early across the Atlantic. But Bishop was a presence who counted for a variety of cisatlantic poets at least from the English publication of her selected poems in 1967, and I am not surprised to find that this “skimmed milk bluey-white” volume is included by Seamus Heaney in his poem “The Bookcase”—an evocation of the sacred books of his reading as a young man: the list comprises Hugh MacDiarmid, Bishop, Yeats, Hardy, Frost, and Dylan Thomas, together with an LP including Frost and Stevens.

The bookcase in question evinces qualities Heaney admires in art:

Ashwood or oakwood? Planed to silkiness,

Mitred, much eyed-along, each vellum-pale

Board in the bookcase held and never sagged.

Virtue went forth from its very ship-shapeness.

The virtue associated with carefully planed boards expertly fitted together, with “carpentered right angles I could feel/In my neck and shoulder,” white boards, or new boards as one might use for a bier or a coffin. It would be pointless, at this stage, to object to this aesthetic: it has served Heaney more than well. But sometimes I cannot help thinking that there must be more to beauty than this: the beauty of a scientific proof or an experiment, for instance, intellectual and imaginative beauty, the gorgeousness of Stevens (of whose poems it would be odd to say that they derive their beauty from their well-planed wooden surfaces and accurately assembled joints). And what is beauty in Bishop? Something not entirely dissimilar to beauty in Klee (a name cited by Reid, and the kind of tutelary spirit, along with Bishop, whose influence I feel I can detect in his work).

Here in “A Norman Simile,” one of the “Ten Glosses,” is a Heaney credo:

To be marvellously yourself like the river water

Gerald of Wales says runs in Arklow harbour

Even at high tide when you’d expect salt water.

It’s a very nicely expressed impossible ideal: let me be like a good, constant source of fresh water. I like this other gloss, “The Bridge,” better:

Steady under strain and strong through tension,

Its feet on both sides but in neither camp,

It stands its ground, a span of pure attention,

A holding action, the arches and the ramp

Steady under strain and strong through tension.

The beauty of a great piece of engineering stands here as a metaphor for the position Heaney has chosen to occupy as a writer in Ireland. Of course there is a difference between being marvelously yourself and repeating yourself, and Heaney has by now expressed himself so abundantly that there are times when he perhaps tends toward the latter, both in subject and in mode of expression. The poem called “Perch” could have come at almost any point in his career—perhaps it is indeed an old poem, why not? And that way of calling the fish “little food-slubs, runty and ready” (enriching the consonantal element in a poem, to emphasize the rough thinginess of nature) reminds us of Heaney’s immediate mentor, Ted Hughes. It is a mannerism that was picked up in paro-dies of either poet decades ago. But Heaney, who has a tribute to Hughes in this latest volume, eclipsed his mentor, and did so—unusually—without ever undermining him. He has remained very much more in the world, a social being and therefore a political one, even if “in neither camp” in a narrower, partisan sense. This may not be his best collection, but one wants to own and think about everything Heaney has written. And I think the same is true of Reid.

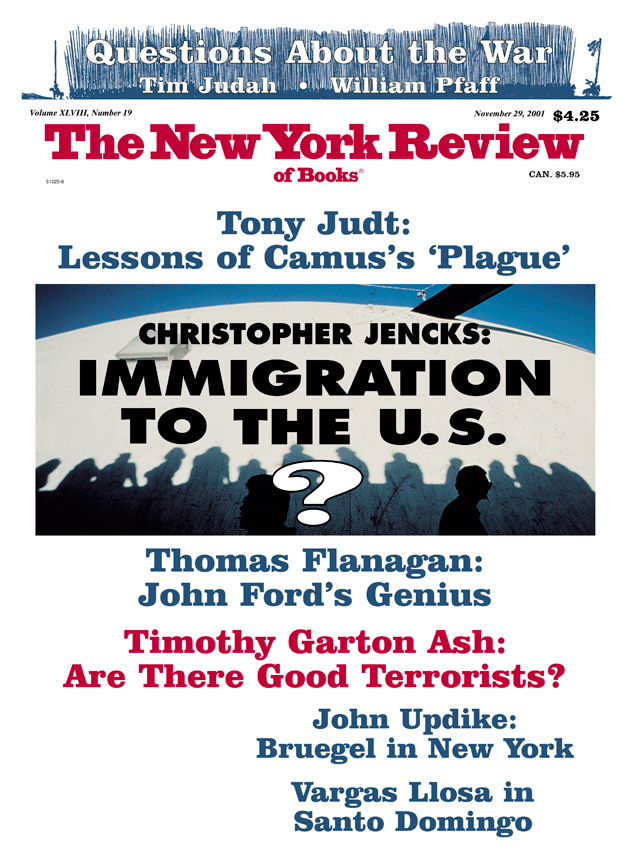

This Issue

November 29, 2001

-

*

See Simplicius Simplicissimus by Johann Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, translated from the German and with an introduction by George Schultz-Behrend (Bobbs-Merrill/Library of Liberal Arts, 1965), p. 334. ↩