1.

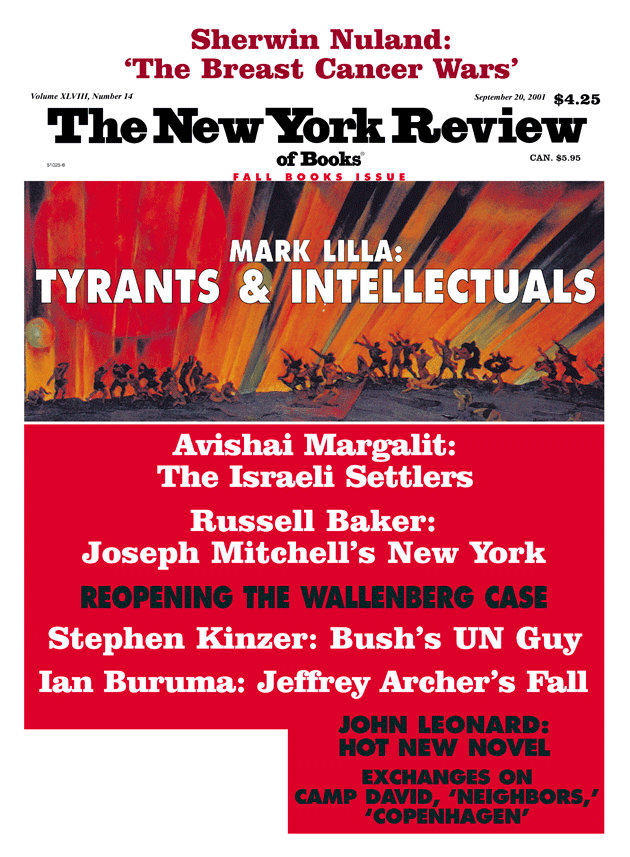

Joseph Mitchell’s New York is long vanished. We can only argue about whose New York has succeeded it, but Tom Wolfe’s, painted in his broad, gaudy burlesque strokes, would have to be considered. With its lunatic obsession with money, New York from Reagan through Giuliani has become too grotesque to be captured by mere satire. Satire is subtle; turn-of-the-millennium New York runs irresistibly to grossness.

In The Bonfire of the Vanities Wolfe has a character die while dining in a fancy East Side restaurant and paints a scene, both hilarious and disgusting, in which the management’s only concerns are to get the body out fast and to collect the bill for the dead man’s unfinished meal. They end up shoving the body through a toilet window. It is hard to recall a more savage literary comment on New York’s character.

Some readers thought Wolfe unjustly cruel to the city, and maybe he was. Still, in the present New York people go out to dinner, pay a thousand dollars a bottle for the wine, and go home to three-million-dollar apartments while others are bedding down on sidewalks in cardboard boxes. Only burlesque can catch the spirit of it.

New Yorks come and go so quickly that literature has trouble keeping up with them. From Washington Irving to Poe to Melville to Whitman to Edith Wharton, somebody’s “old New York” has always been turning into a new city. Joseph Mitchell became its chronicler as F. Scott Fitzgerald was leaving the scene, and Mitchell’s city would have absolutely none of the gauzy romantic charm of Fitzgerald’s. Fitzgerald’s New York was a 1920 prairie boy’s dream of white towers and gloriously desirable girls, but Daisy Buchanan already belonged to a past as remote as Lillian Russell and Boss Tweed on the day Mitchell arrived in town. That was October 25, 1929. The stock market had crashed the day before.

Mitchell was not much for romantic charm anyhow, but in a dark time he saw and painted the city as a place with a great sweetness of character which eased the hard lives he recorded. His New York was born of the crash, hardened by the Great Depression, civilized by the sense of mission generated by World War II, and made genial by the Eisenhower era’s sense of well-being.

When he stopped writing in the 1960s the inevitable change was almost complete. The martini hour was ending; marijuana, hallucinogens, and the needle in the arm were the new way. The tinkling piano in the next apartment was giving way to the guitar in the park. People now had so much money that they could afford to look poor. Men quit wearing fedoras and three-piece suits to Yankee Stadium and affected a hobo chic—all whiskers and no creases. Women quit buying hats and high-heeled shoes and started swearing like Marine sergeants. College students, who had once rioted for the pure joy of it, began rioting for moral and political uplift, issued non-negotiable demands, held the dean hostage, and blew up the physics lab. Gangster funerals disappeared into the back of the newspapers, upstaged by spectacular nationally televised funerals of murdered statesmen.

Mitchell stopped writing, but through the middle third of the twentieth century he had created a tapestry of New York lives comparable to Charles Dickens’s astonishing assortment of Victorian Londoners. To be sure, Dickens’s most memorable people were fictional while Mitchell’s had all actually lived and breathed, but just as Dickens’s fictional Londoners seem more real than life, Mitchell’s real New Yorkers seem born to live in novels.

In McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon, he produces Charles Eugene Cassell, who operates Captain Charley’s Private Museum for Intelligent People in a Fifty-ninth Street basement, admission fifteen cents when he remembers to collect it. Captain Charley brings to mind Dickens’s Mr. Venus, the taxidermist in Our Mutual Friend, who has acquired the rascally Silas Wegg’s amputated leg bone. Mitchell reports visiting the museum one day to find the Captain “searching for a bone which he said he hacked off an Arab around 9 PM one full-moon night in 1907 after the Arab had been murdered for signing a treaty….”

Like Dickens, Mitchell roamed his city looking for people worth preserving in stories. Dickens found the makings of Sairy Gamp, Mister Bumble, and Gaffer Hexam, who fished the Thames for corpses of men who might have drowned with money in their pockets. Mitchell found Cockeye Johnny, one of New York’s several gypsy “kings,” and through him learned of the superior cunning of gypsy women and how to operate a classic swindle the gypsies called “bajour”; Commodore Dutch, who for forty years made his living by giving an annual ball for the benefit of himself; and Arthur Samuel Colborne, founder of the Anti-Profanity League, who devoted his life to stamping out cussing in New York, or, as Colborne put it, “cleaning up profanity conditions.”

Advertisement

I’m past seventy, but I’m a go-getter, fighting the evil on all fronts. Keeps me busy. I’m just after seeing a high official at City Hall. There’s some Broadway plays so profane it’s a wonder to me the tongues of the actors and the actresses don’t wither up and come loose at the roots and drop to the ground, and I beseeched this high official to take action. Said he’d do what he could. Probably won’t do a single, solitary thing.

It won’t do to press the Dickens parallel too hard. Mitchell himself doesn’t seem to have been especially interested in Dickens. His favorite writers were Mark Twain and James Joyce. His passion for Joyce ran so deep that he guessed he’d read Finnegans Wake a half-dozen times. Moreover, though Dickens and Mitchell both began as reporters fascinated by the dark side of city life, Dickens was a deep-dyed moralizer whose journalistic style would have horrified Mitchell. In The Uncommercial Traveler, a book of reporting, Dickens visits a London workhouse, views the bleak lives of the aged, sick, addled, and orphaned paupers who are stored in such places in 1850, and writes:

In ten minutes I had ceased to believe in such fables of a golden time as youth, the prime of life, or a hale old age. In ten minutes, all the lights of womankind seemed to have been blown out, and nothing in that way to be left this vault to brag of, but the flickering and expiring snuffs.

This is classic Dickens on an emotional binge, and it would have appalled Mitchell. Dickens’s inability to keep his passions out of his writing may have helped make him a great novelist, but it made for some very bad journalism. Mitchell, whose few attempts at fiction were not notably successful, was incapable of sermonizing about the hardships of his subjects. Serious reporters were not supposed to do that, and he thought of himself as a reporter, not a man of letters. He was trained in the hard discipline of an old-fashioned journalism whose code demanded self-effacement of the writer. A reporter’s effusions about his own inner turmoil were taboo.

The discipline by which he worked required something like the artistry needed to compose good music: the writer had to stir an emotional or intellectual response in his audience without telling them how to feel or think. The portraits of people who caught his fancy are worth close study by writers who want to learn how to move an audience without preaching a lesson. These pieces usually start as if they are going to be funny, then almost deliberately deceive this expectation and become touching and sometimes terribly sad, as in “Lady Olga.”

Here his subject is Jane Barnell, a sixty-nine-year-old woman whose life has been spent as a “bearded lady” in circus sideshows. She has a thick, curly, gray beard thirteen-and-a-half inches long and is working in the basement sideshow of Hubert’s Museum on Forty-second Street when Mitchell meets her in 1940. She has recently left Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey because union trouble ended its season and is afraid that if she goes back “that union will get me.” A “violently opinionated Republican,” though she never votes, she believes everything she reads in the Hearst newspapers and assumes “the average union organizer carries a gun and will shoot to kill.”

But Mitchell is not dwelling on her “freakishness” to provide the reader with a supercilious smile. He is out to explore what it means to be a “freak” in America, and the notion that we are going to be titillated with anecdotes about Miss Barnell’s bizarre appearance vanishes as he piles up details. What emerges is a portrait of a woman who has spent most of her life in pain:

In an expansive mood, she will brag that she has the longest female beard in history and will give the impression that she feels superior to less spectacular women. Every so often, however, hurt by a snicker or a brutal remark made by someone in an audience, she undergoes a period of depression that may last a few hours or a week. “When I get the blues, I feel like an outcast from society,” she once said. “I used to think when I got old my feelings wouldn’t get hurt, but I was wrong. I got a tougher hide than I once had, but it ain’t tough enough.”

Because Miss Barnell’s sideshow colleagues were touchy about the word “freak,” the Ringling circus—in a prehistoric concession to political correctness—changed the name of its Congress of Freaks to Congress of Strange People. Miss Barnell cannot cheer. “No matter how nice a name was put on me,” she tells Mitchell, “I would still have a beard.” Considering herself engaged in show business as truly as any Broadway actor, she holds that “a freak is just as good as any actor, from the Barrymores on down.” Mitchell lets her speak the closing line of his story, perhaps because it speaks the message he would speak himself if he felt free to preach as Dickens did: “‘If the truth was known, we’re all freaks together,’ she says.”

Advertisement

2.

Although Mitchell wrote voluminously about the kind of people the world happily ignored until he wrote about them, he wrote very little about himself. My Ears Are Bent, written in 1938, was his only extended exercise in self-advertisement. It is a small, modest book about his early newspaper days with the Herald Tribune and the World-Telegram. Published when he was thirty, it was out of print for decades, but is now back in the shops in a new, slightly refreshed edition issued by Pantheon.

This is not the mature, polished work of the later New Yorker pieces, but the writing is already remarkable for its economy, precision, and power to get at what makes odd people more interesting than their oddness. From the very beginning he seems to have had a perfect ear for the astonishing quotation; he cannot resist telling of the streetwalker who, asked why she had become a prostitute, replied, “I just wanted to be accommodating.”

The people he liked writing about as a young reporter foreshadowed the kind of people who later filled his long New Yorker profiles, all of which are now collected in the 1992 Up in the Old Hotel and the new reissue of McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon. They were people who were “sadly or humorously out of step with the world,” as Brendan Gill described them. Mitchell found them in places to which middle-class New Yorkers paid little attention: the Bowery, the waterfront, the fish market, Times Square corners where preachers harangued passing sinners, and workingmen’s saloons where bartenders were gentle when tossing out a panhandler.

It was usually said that his subjects were “eccentrics.” This is journalistic lingo for people who are notably different from the run-of-the-mine population but neither successful nor rich enough to merit journalistic attention. Mitchell seemed to reason that, regardless of being unsuccessful or poor, eccentricity might make them more interesting than the run-of-the-mine majority, and he cultivated them from his early newspaper days. When the news was slow they might provide a small human-interest feature.

Among the specimens he found was a man named Reidt who was obsessed with predicting the end of the world—“always going up on a hilltop…with his family to await destruction.” The Reidt connection finally paid off one dull news day when Mitchell “called him up to ask if he had any advance information on the crack of doom and the telephone operator said, ‘Mr. Reidt’s telephone has been disconnected.'”

A reporter writing features in New York papers also met eccentrics who were successful and well-heeled. He sketched a few in this early book. George Bernard Shaw is here. Huey Long sits in bed with a hangover at the Waldorf-Astoria, wearing baby-blue pajamas, scratching his toes, and telling a long incoherent story about a relative who owned a saloon. Billy Sunday, the old baseball player turned evangelist (“Hit a home run for Jesus!”), is interviewed in bed too at his hotel, wearing woolen winter underwear, scratching his itching back, and husbanding his strength for the night’s revival meeting. (“I wanted to take me a walk around town…but Ma made me get in bed and take a nap.”) He takes a ride with Mary Louise Cecilia (Texas) Guinan in her bullet-proof limousine, talks about her playing the role of Aimee Semple McPherson on Broadway, suggests that Mrs. McPherson would surely sue the producer, and faithfully records Miss Guinan’ s response. (“‘That,’ said Miss Guinan, ‘is no skin off my ass.'”)

Most of those mentioned here were more interesting than famous. Among them is Florence Cubitt, sitting in an overstuffed hotel room chair wearing only a G-string and “a cheerful baby face,” the only garb appropriate when “Tanya, Queen of the Nudists” submits to an interview. To promote her career she has taken the name Tanya in the belief that “Tanya sounds more sexy than Florence.” She has been performing at a trade fair in San Diego and is in town with a press agent to stir up demand for including a nude show at the coming New York World’s Fair of 1939. She explains that in the San Diego show twenty young women and five men played games in the nude on a big field while customers (ad-mission forty cents) watched from a distance.

“The men nudists are a bunch of nuts,” she tells Mitchell. “Why, they eat peas right out of the pod. They squeeze the juice out of vegetables and drink it, and they don’t eat salt. Also, they have long beards. They don’t have any ambition. They just want to be nudists all their lives.” Then, in her tribute to the nudist life, Mitchell catches a glimpse of innocence too unspoiled to be believed:

“It keeps us out in the open,” said Miss Cubitt. “It doesn’t keep us out late at night, and we have a healthy atmosphere to work in. My girl friends think we have orgies and all, but I never had an orgy yet. Sometimes when the sun is hot, nudism is hard work.”

This early book is a rare instance of Mitchell writing—at least a little—about himself. By the end of the very first page he has told us he comes from North Carolina, attended the university at Chapel Hill, left it (doesn’t say why), and while recuperating from an appendectomy read James Bryce’s American Commonwealth, which made him want to become a political reporter, so came to New York at the age of twenty-one “with that idea in mind.”

This is surely the most modest newspaper reporter since Gutenberg first inked a press: not a word about his family history, his childhood, his educational travails, his youthful loves and hates, his early triumphs and humiliations, how he started writing, why he decided to come to New York, or how a self-effacing youngster from the sticks was able to land a job on the elegant Herald Tribune.

The Tribune sent him up to Harlem to cover police stories, and he found himself sitting in a swivel chair in the doorway of the Theresa Hotel watching the passing parade on Seventh Avenue. In Harlem he found his calling, and it was not political reporting. Harlem fascinated him. He had grown up white in the South during a stifling and benighted racist era, and the freedom he found in Harlem seems to have been exhilarating:

I was alternately delighted and frightened out of my wits by what I saw at night in Harlem. I would go off duty at 3 AM, and then I would walk around the streets and look, discovering what the depression and the prurience of white men were doing to a people who are “last to be hired; first to be fired.”

He might “drop into a speakeasy or a night club or a gambling flat and try to pull a story out of it. I got to know a few underworld figures and I used to like to listen to them talk.”

His New Yorker stories are told in great rivers of talk to which Mitchell seems to have listened so intensely that the talker couldn’t resist talking more, and more, and more. He had the gift of listening, but what made him special was his knack for finding people worth listening to. In My Ears Are Bent, he discussed how to find them:

The only people I do not care to listen to are society women, industrial leaders, distinguished authors, ministers, explorers, moving picture actors (except W.C. Fields and Stepin Fetchit), and any actress under the age of thirty-five. I believe the most interesting human beings, so far as talk is concerned, are anthropologists, farmers, prostitutes, psychiatrists, and an occasional bartender. The best talk is artless, the talk of people trying to reassure or comfort themselves, women in the sun, grouped around baby carriages, talking about their weeks in the hospital or the way meat has gone up, or men in saloons, talking to combat the loneliness everyone feels.

3.

Mitchell, who died in 1996, published almost nothing during the final thirty years of his life. He did not announce that he was going out of business or retire to enjoy rustic solitude and ostentatiously refuse to grant interviews. He did not clean out his desk while mourning colleagues watched. He did not even stop coming to the office.

Only gradually was it observed that, while he came to the office as regularly as ever, he no longer submitted anything for publication. His office was at The New Yorker, a magazine then famous for not pressing writers to produce. Even in his prime Mitchell had been known there as a man who took his good old time with a story. “Excellent quality, low productivity,” Harold Ross, the magazine’s founder-editor said of him in 1946.

It worried people that he quit writing. American writers are conditioned by the nation’s market cultur e to suppose that no amount of success can explain why a writer sound of mind and body should cease production after thirty or forty years of what, for most writers at least, is an extremely exacting and decidedly lonely line of work. When it happens the publishing world is troubled. Something psychologically alarming must have happened. People want an explanation.

Calvin Trillin, who knew Mitchell during the years of silence, treats the silence lightly in his foreword to McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon:

During the decades when Mitchell came to the offices of The New Yorker every day but never turned anything in, one of the many fanciful stories heard as an explanation for his silence was that he had been writing at the same pace as everyone else until some college professor said that he was the greatest master of the English declarative sentence in America, and that this encomium had stopped him cold.

This suggests that the fancies of Mitchell’s colleagues tended toward the idea of “writer’s block,” a disease especially widespread among college students that leaves its victim’s writing faculties in a state of paralysis, rendering him powerless to put words on paper for fear they may reveal he is not yet Shakespeare’s equal. Since it is a disease of egocentrics (also of people who want to be famous writers but don’t much like to write), Mitchell would have been immune; as a reporter he always left his ego at home when he went to work.

As for paralysis, there is evidence that in his eighties he could write as gracefully as he wrote at forty and fifty. When Up in the Old Hotel was published in 1992, Mitchell, then eighty-four, contributed an “Author’s Note” remarkable for the beauty with which it evoked a sense of his childhood. Never before had he written so intimately about himself. It contained a hint that he had been amused by his colleagues’ curiosity about the long silence. “I am sure that most of the influences responsible for one’s cast of mind are too remote and mysterious to be known,” he wrote, and then—in an extraordinary concession—went on to say, “but I happen to know a few of the influences responsible for mine.”

And he wrote of summer Sundays in a Southern childhood.

Like so many who wrote so well about New York, he was an out-of-towner. He was born in 1908 into a well-to-do North Carolina farm family and raised in a small town misnamed Fairmont—“no monts in or around it or anywhere near it,” he wrote. It was situated some sixty miles from the ocean in an area of flat, rich, black farmland intercut with swamp waters and piney woods. The family had grown cotton, tobacco, corn, and timber in that part of the world since before the Revolutionary War.

As in a lot of the rural South, families there commonly buried the dead in their farm fields, creating small private cemeteries shaded by groves of cedar or magnolia and enclosed by cast-iron fences. Generations of Mitchell kin were scattered among these small burying grounds, and they were not allowed to be forgotten quickly. On Sundays the family went for drives along country roads:

Now and then my father would stop the car and we would get out and visit one of those cemeteries, and my father or mother would tell us gravestone by gravestone who the people were who were buried there and exactly how they were related to us. I always enjoyed those visits.

Summertime brought a traditional family watermelon-cutting ceremony in a picnic grove behind an old church his mother’s ancestors had helped build. When the melons were eaten and family talk was winding down and the afternoon was getting late, his Aunt Annie would lead a procession into the cemetery talking about the past, now and then pausing at a grave to “tell us about the man or woman down below.” Some of her memories were “horrifying,” some “horrifyingly funny.”

Here were the cultural odds and ends associated with the making of the “Southern writer”: cemeteries and ancestors, family get-togethers behind the church Grandfather helped to build, Sunday drives down country roads. And those watermelons—in his eighties Mitchell could still see them, “pulled early that morning in our own gardens—long, heavy, green-striped Georgia Rattlesnakes and big, round, heavy Cuban Queens so green they were almost black.”

Looking back at his work in old age, he was “surprised and pleased” to find it filled with what he thought was “graveyard humor.” In some it was “what the story is all about,” he said, and it pleased him that the work was so full of it because “graveyard humor is an exemplification of the way I look at the world.”

It doesn’t seem odd that he should have stopped writing when he did. He had done it a for a very long time, and though he had been terribly good at what he did, after awhile one must lose his zest for doing it again and again. Artie Shaw is said to have quit performing because he couldn’t bear having to play “Frenesi” one more time. In any event, Mitchell doesn’t seem to have needed the money (Brendan Gill said his family was “wealthy”), and he took great pleasure in New York’s amenities, including the Metropolitan Museum, the Grand Central Oyster Bar, and of course McSorley’s alehouse.

What does seem odd is that a man with the memory of those Carolina Sundays in his bones should have found the New York of the middle third of the twentieth century the ideal subject for his civilized form of graveyard humor. But the New York emerging in the 1960s was not a city that lent itself to his particular “cast of mind.” It needed writers who had grown up hearing the roar of the bullhorn, not the voice of Aunt Annie talking about the people down below.

This Issue

September 20, 2001