To the Editors:

In “The Big College Try” [NYR, April 12], Andrew Hacker challenges Murray Sperber’s thesis that big-time college sports play a major role in shaping undergraduate education (Beer and Circus: How Big-Time College Sports Is Crippling Undergraduate Education). Specifically, Hacker questions the extent to which college sports influence the lives of students given that relatively few attend the games or participate in sports-related celebrations.

I do not believe that measures such as attendance at athletic events can begin to capture the sports culture that so dominates the universities with big-time college sports. I have taught at a variety of institutions including a small liberal arts college and a major university and I have been amazed at the role that college football plays in Division I schools. To cite an example: at least one Division I school canceled classes one day this past September to celebrate a victory of its football team. Even if most students do not attend the games, the emphasis on college sports infiltrates the intellectual and social atmosphere of the university.

In my experience, this athletic culture has been accompanied by a certain degree of anti-intellectualism and for this reason it negatively affects teaching and learning in the university. This anti-intellectualism plays itself out in different ways and includes cheating, non-attendance, late assignments, a lack of studying, and disruptive behavior in the classroom. The experience of students who are serious about learning is inevitably compromised by this atmosphere and classroom management becomes a priority. While I do agree that most undergraduate students seek challenging curricula, I feel as though certain disciplines become dumping grounds for students who are seeking an easy ride, including many athletes. For this reason, the experience of faculty at schools with big-time college sports can vary tremendously across fields, and even from professor to professor.

I have always felt the student athletes are one of the biggest victims of all in what Sperber dubs “Beer and Circus.” The athletes are exploited for their physical abilities and many are overwhelmed by demands which require them to balance both athletic and academic achievement. Many of the athletes arrive ill-prepared for the academic demands of a major university; they have been admitted based on athletic rather than academic achievement. Moreover, their academic experience is further compromised by the fact that they must miss classes to attend games and much of their time outside the classroom is consumed by athletic practice. Consequently, many never have the opportunity to fully challenge themselves intellectually and a sizable proportion never graduate. That is one cost that has no price tag.

Esther I. Wilder

Norman, Oklahoma

To the Editors:

In making the inane assertion that “I myself fully favor physical exertion” and going on to list his enthusiasm for, among other near-sedentary sports, “Central Park croquet,” Andrew Hacker in one stroke displays his complete ignorance of the college athletics framework of which he is so evidently skeptical in his review.

As a former member of the Varsity Heavyweight Crew at Yale (as well as, incidentally, a former student in reviewee James Shulman’s Shakespeare class there), I can assure Mr. Hacker that “physical exertion,” as he and millions of others profitably practice it, bears little or no resemblance to intercollegiate competition at the highest levels. While the former merely requires time, space, and inclination, the latter takes something several orders of magnitude higher and more rare: discipline. Day after day, month after month, year after year, to compete at these levels requires not only major sacrifices but also a toughness, fortitude, and sense of purpose that are simply not demanded of those who participate in, say, the school paper or the drama club. This discipline, I would argue, is an essential part of a meaningful education.

And I am not, I think, alone. Oliver Wendell Holmes once said of the Yale–Harvard boat race—the first intercollegiate sporting event—“Is life less than a boat race? And if a man will give all the blood in his body to win one, will he not spend all the might of his soul to prevail in the other?”

Estep Nagy

New York City

Andrew Hacker replies:

Estep Nagy argues that “intercollegiate competition at the highest levels…is an essential part of a meaningful education.” I am sure that the discipline demanded by the Yale crew helped to make him the man he is today. But he also seems to be saying that every student must undergo such a regimen to get the best that college can offer. Has he evidence that varsity athletes develop more distinctive lives than their more sedentary classmates?

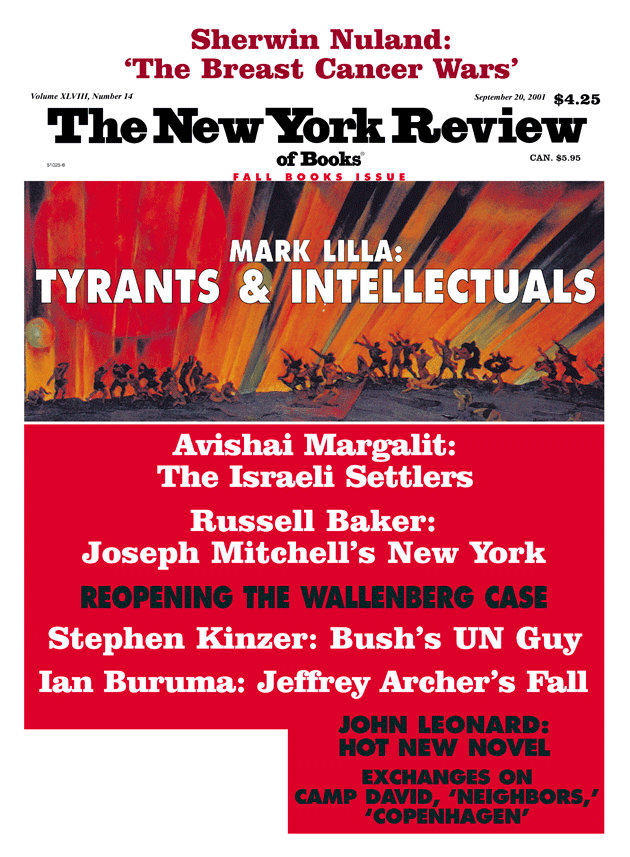

This Issue

September 20, 2001